Reaction calorimeter

A reaction calorimeter is a calorimeter that measures the amount of energy released (exothermic) or absorbed (endothermic) by a chemical reaction. These measurements provide a more accurate picture of such reactions.

Applications

When considering scaling up a reaction to large scale from lab scale, it is important to understand how much heat is released. At a small scale heat released may not cause a concern, however when scaling up, that heat can build up and be extremely dangerous.

Crystallizing a reaction product from solution is a highly cost effective purification technique. It is therefore valuable to be able to measure how effectively crystallization is taking place in order to be able to optimize it. The heat absorbed by the process can be a useful measure.

The energy being released by any process in the form of heat is directly proportional to the rate of reaction and hence reaction calorimetry (as a time resolved measurement technique) can be used to study kinetics.

The use of reaction calorimetry in process development has been historically limited due to the cost implications of these devices however calorimetry is a fast and easy way to fully understand the reactions which are conducted as part of a chemical process.

Heat flow calorimetry

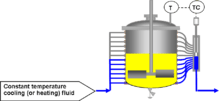

Heat flow calorimetry measures the heat flowing across the reactor wall and quantifying this in relation to the other energy flows within the reactor.

where

- = process heating (or cooling) power (W)

- = overall heat transfer coefficient (W/(m2K))

- = heat transfer area (m2)

- = process temperature (K)

- = jacket temperature (K)

Heat flow calorimetry allows the user to measure heat whilst the process temperature remains under control. While the driving force Tr − Tj is measured with a relatively high resolution, the overall heat transfer coefficient U or the calibration factor UA respectively, is determined by means of calibration before and after the reaction takes place. The calibration factor UA (or the overall heat transfer coefficient U) are affected by the product composition, process temperature, agitation rate, viscosity, and the liquid level. Good accuracy can be achieved with experienced staff who know the limitations and how to get the best results from an instrument.

Real-time calorimetry

Calorimetry in real time is a calorimetry technique based on heat flux sensors that are located on the wall of the reactor vessels. The sensors measure heat across the reactor wall directly and thus, the measurement is independent of temperature, the properties or the behavior of the reaction mass. Heat flow as well as heat transfer information are obtained immediately without any calibrations during the experiment.

Heat balance calorimetry

In heat balance calorimetry, the cooling/heating jacket controls the temperature of the process. Heat is measured by monitoring the heat gained or lost by the heat transfer fluid.

where

- = process heating (or cooling) power (W)

- = mass flow of heat transfer fluid (kg/s)

- = specific heat of heat transfer fluid (J/(kg K))

- = inlet temperature of heat transfer fluid (K)

- = outlet temperature of heat transfer fluid (K)

Heat balance calorimetry is, in principle, the ideal method of measuring heat since the heat entering and leaving the system through the heating/cooling jacket is measured from the heat transfer fluid (which has known properties). This eliminates most of the calibration problems encountered by heat flow and power compensation calorimetry. Unfortunately, the method does not work well in traditional batch vessels since the process heat signal is obscured by large heat shifts in the cooling/heating jacket.

Power compensation calorimetry

A variation of the 'heat flow' technique is called 'power compensation' calorimetry. This method uses a cooling jacket operating at constant flow and temperature. The process temperature is regulated by adjusting the power of the electrical heater. When the experiment is started, the electrical heat and the cooling power (of the cooling jacket) are in balance. As the process heat load changes, the electrical power is varied in order to maintain the desired process temperature. The heat liberated or absorbed by the process is determined from the difference between the initial electrical power and the demand for electrical power at the time of measurement. The power compensation method is easier to set up than heat flow calorimetry but it suffers from the similar limitations since any change in product composition, liquid level, process temperature, agitation rate or viscosity will upset the calibration. The presence of an electrical heating element is also undesirable for process operations. The method is further limited by the fact that the largest heat it can measure is equal to the initial electrical power applied to the heater.

- = current supplied to heater

- = voltage supplied to heater

- = current supplied to heater at equilibrium (assuming constant voltage / resistance)

Constant flux calorimetry

A recent development in calorimetry, however, is that of constant flux cooling/heating jackets. These use variable geometry cooling jackets and can operate with cooling jackets at substantially constant temperature. These reaction calorimeters tend to be much simpler to use and are much more tolerant of changes in the process conditions (which would affect calibration in heat flow or power compensation calorimeters).

A key part of reaction calorimetry is the ability to control temperature in the face of extreme thermal events. Once the temperature is able to be controlled, measurement of a variety of parameters can allow an understanding of how much heat is being released of absorbed by a reaction.

In essence, constant flux calorimetry is a highly developed temperature control mechanism which can be used to generate highly accurate calorimetry. It works by controlling the jacket area of a controlled lab reactor, while keeping the inlet temperature of the thermal fluid constant. This allows the temperature to be precisely controlled even under strongly exothermic or endothermic events as additional cooling is always available by simply increasing the area over which the heat is being exchanged.

This system is generally more accurate than heat balance calorimetry (on which it is based), as changes in the delta temperature (Tout - Tin) are magnified by keeping the fluid flow as low as possible.

One of the main advantages of constant flux calorimetry is the ability to dynamically measure heat transfer coefficient (U). We know from the heat balance equation that:

- Q = mf.Cpf.Tin - Tout

We also know that from the heat flow equation that

- Q = U.A.LMTD

We can therefore rearrange this such that

- U = mf.Cpf.Tin - Tout /A.LMTD

This will allow us therefore to monitor U as a function of time.