Recrystallization (metallurgy)

Recrystallization is a process by which deformed grains are replaced by a new set of defects-free grains that nucleate and grow until the original grains have been entirely consumed. Recrystallization is usually accompanied by a reduction in the strength and hardness of a material and a simultaneous increase in the ductility. Thus, the process may be introduced as a deliberate step in metals processing or may be an undesirable byproduct of another processing step. The most important industrial uses are the softening of metals previously hardened by cold work, which have lost their ductility, and the control of the grain structure in the final product.

Definition

It is defined as the process in which grains of a crystal structure come in new structure or new crystal shape.

A precise definition of recrystallization is difficult to state as the process is strongly related to several other processes, most notably recovery and grain growth. In some cases it is difficult to precisely define the point at which one process begins and another ends. Doherty et al. (1997) defined recrystallization as:

"... the formation of a new grain structure in a deformed material by the formation and migration of high angle grain boundaries driven by the stored energy of deformation. High angle boundaries are those with greater than a 10-15° misorientation"

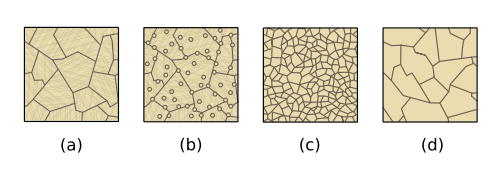

Thus the process can be differentiated from recovery (where high angle grain boundaries do not migrate) and grain growth (where the driving force is only due to the reduction in boundary area). Recrystallization may occur during or after deformation (during cooling or a subsequent heat treatment, for example). The former is termed dynamic while the latter is termed static. In addition, recrystallization may occur in a discontinuous manner, where distinct new grains form and grow, or a continuous manner, where the microstructure gradually evolves into a recrystallised microstructure. The different mechanisms by which recrystallization and recovery occur are complex and in many cases remain controversial. The following description is primarily applicable to static continuous recrystallization, which is the most classical variety and probably the most understood. Additional mechanisms include (geometric) dynamic recrystallization and strain induced boundary migration...

Laws of recrystallization

There are several, largely empirical laws of recrystallization:

- Thermally activated. The rate of the microscopic mechanisms controlling the nucleation and growth of recrystallized grains depend on the annealing temperature. Arrhenius-type equations indicate an exponential relationship.

- Critical temperature. Following from the previous rule it is found that recrystallization requires a minimum temperature for the necessary atomic mechanisms to occur. This recrystallization temperature decreases with annealing time.

- Critical deformation. The prior deformation applied to the material must be adequate to provide nuclei and sufficient stored energy to drive their growth.

- Deformation affects the critical temperature. Increasing the magnitude of prior deformation, or reducing the deformation temperature, will increase the stored energy and the number of potential nuclei. As a result, the recrystallization temperature will decrease with increasing deformation.

- Initial grain size affects the critical temperature. Grain boundaries are good sites for nuclei to form. Since an increase in grain size results in fewer boundaries this results in a decrease in the nucleation rate and hence an increase in the recrystallization temperature

- Deformation affects the final grain size. Increasing the deformation, or reducing the deformation temperature, increases the rate of nucleation faster than it increases the rate of growth. As a result, the final grain size is reduced by increased deformation.

Driving force

During plastic deformation the work performed is the integral of the stress and strain in the plastic deformation regime. Although the majority of this work is converted to heat, some fraction (~1-5%) is retained in the material as defects - particularly dislocations. The rearrangement or elimination of these dislocations will reduce the internal energy of the system and so there is a thermodynamic driving force for such processes. At moderate to high temperatures, particularly in materials with a high stacking fault energy such as aluminium and nickel, recovery occurs readily and free dislocations will readily rearrange themselves into subgrains surrounded low-angle grain boundaries. The driving force is the difference in energy between the deformed and recrystallized state ΔE which can be determined by the dislocation density or the subgrain size and boundary energy (Doherty, 2005):

where ρ is the dislocation density, G is the shear modulus, b is the Burgers vector of the dislocations, γ is the sub-grain boundary energy and ds is the subgrain size.

Nucleation

Historically it was assumed that the nucleation rate of new recrystallized grains would be determined by the thermal fluctuation model successfully used for solidification and precipitation phenomena. In this theory it is assumed that as a result of the natural movement of atoms (which increases with temperature) small nuclei would spontaneously arise in the matrix. The formation of these nuclei would be associated with an energy requirement due to the formation of a new interface and an energy liberation due to the formation of a new volume of lower energy material. If the nuclei were larger than some critical radius then it would be thermodynamically stable and could start to grow. The main problem with this theory is that the stored energy due to dislocations is very low (0.1-1 Jm−3) while the energy of a grain boundary is quite high (~0.5Jm−2). Calculations based on these values found that the observed nucleation rate was greater than the calculated one by some impossibly large factor (~1050).

As a result, the alternate theory proposed by Cahn in 1949 is now universally accepted. The recrystallized grains do not nucleate in the classical fashion but rather grow from pre-existing sub-grains and cells. The 'incubation time' is then a period of recovery where sub-grains with low-angle boundaries (<1-2°) begin to accumulate dislocations and become increasingly misoriented with respect to their neighbors. The increase in misorientation increases the mobility of the boundary and so the rate of growth of the sub-grain increases. If one sub-grain in a local area happens to have an advantage over its neighbors (such as locally high dislocation densities, a greater size or favorable orientation) then this sub-grain will be able to grow more rapidly than its competitors. As it grows its boundary becomes increasingly misoriented with respect to the surrounding material until it can be recognized as an entirely new strain-free grain.

Kinetics

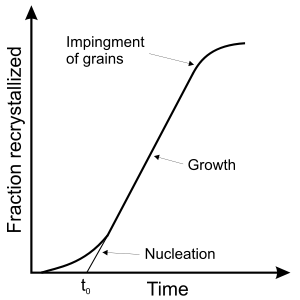

Recrystallization kinetics are commonly observed to follow the profile shown. There is an initial 'nucleation period' t0 where the nuclei form, and then begin to grow at a constant rate consuming the deformed matrix. Although the process does not strictly follow classical nucleation theory it is often found that such mathematical descriptions provide at least a close approximation. For an array of spherical grains the mean radius R at a time t is (Humphreys and Hatherly 2004):

where t0 is the nucleation time and G is the growth rate dR/dt. If N nuclei form in the time increment dt and the grains are assumed to be spherical then the volume fraction will be:

This equation is valid in the early stages of recrystallization when f<<1 and the growing grains are not impinging on each other. Once the grains come into contact the rate of growth slows and is related to the fraction of untransformed material (1-f) by the Johnson-Mehl equation:

While this equation provides a better description of the process it still assumes that the grains are spherical, the nucleation and growth rates are constant, the nuclei are randomly distributed and the nucleation time t0 is small. In practice few of these are actually valid and alternate models need to be used.

It is generally acknowledged that any useful model must not only account for the initial condition of the material but also the constantly changing relationship between the growing grains, the deformed matrix and any second phases or other microstructural factors. The situation is further complicated in dynamic systems where deformation and recrystallization occur simultaneously. As a result, it has generally proven impossible to produce an accurate predictive model for industrial processes without resorting to extensive empirical testing. Since this may require the use of industrial equipment that has not actually been built there are clear difficulties with this approach.

Factors influencing the rate

The annealing temperature has a dramatic influence on the rate of recrystallization which is reflected in the above equations. However, for a given temperature there are several additional factors that will influence the rate.

The rate of recrystallization is heavily influenced by the amount of deformation and, to a lesser extent, the manner in which it is applied. Heavily deformed materials will recrystallize more rapidly than those deformed to a lesser extent. Indeed, below a certain deformation recrystallization may never occur. Deformation at higher temperatures will allow concurrent recovery and so such materials will recrystallize more slowly than those deformed at room temperature e.g. contrast hot and cold rolling. In certain cases deformation may be unusually homogeneous or occur only on specific crystallographic planes. The absence of orientation gradients and other heterogeneities may prevent the formation of viable nuclei. Experiments in the 1970s found that molybdenum deformed to a true strain of 0.3, recrystallized most rapidly when tensioned and at decreasing rates for wire drawing, rolling and compression (Barto & Ebert 1971).

The orientation of a grain and how the orientation changes during deformation influence the accumulation of stored energy and hence the rate of recrystallization. The mobility of the grain boundaries is influenced by their orientation and so some crystallographic textures will result in faster growth than others.

Solute atoms, both deliberate additions and impurities, have a profound influence on the recrystallization kinetics. Even minor concentrations may have a substantial influence e.g. 0.004% Fe increases the recrystallization temperature by around 100 °C (Humphreys and Hatherly 2004). It is currently unknown whether this effect is primarily due to the retardation of nucleation or the reduction in the mobility of grain boundaries i.e. growth.

Influence of second phases

Many alloys of industrial significance have some volume fraction of second phase particles, either as a result of impurities or from deliberate alloying additions. Depending on their size and distribution such particles may act to either encourage or retard recrystallization.

Small particles

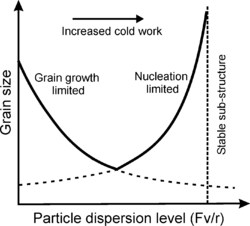

Recrystallization is prevented or significantly slowed by a dispersion of small, closely spaced particles due to Zener pinning on both low- and high-angle grain boundaries. This pressure directly opposes the driving force arising from the dislocation density and will influence both the nucleation and growth kinetics. The effect can be rationalized with respect to the particle dispersion level where is the volume fraction of the second phase and r is the radius. At low the grain size is determined by the number of nuclei, and so initially may be very small. However the grains are unstable with respect to grain growth and so will grow during annealing until the particles exert sufficient pinning pressure to halt them. At moderate the grain size is still determined by the number of nuclei but now the grains are stable with respect to normal growth (while abnormal growth is still possible). At high the unrecrystallized deformed structure is stable and recrystallization is suppressed.

Large particles

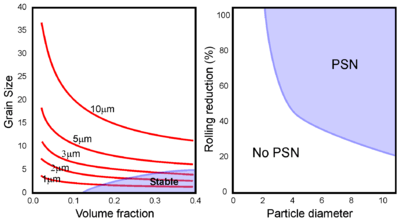

The deformation fields around large (over 1 μm) non-deformable particles are characterised by high dislocation densities and large orientation gradients and so are ideal sites for the development of recrystallization nuclei. This phenomenon, called particle stimulated nucleation (PSN), is notable as it provides one of the few ways to control recrystallization by controlling the particle distribution.

The size and misorientation of the deformed zone is related to the particle size and so there is a minimum particle size required to initiate nucleation. Increasing the extent of deformation will reduce the minimum particle size, leading to a PSN regime in size-deformation space. If the efficiency of PSN is one (i.e. each particle stimulates one nuclei), then the final grain size will be simply determined by the number of particles. Occasionally the efficiency can be greater than one if multiple nuclei form at each particle but this is uncommon. The efficiency will be less than one if the particles are close to the critical size and large fractions of small particles will actually prevent recrystallization rather than initiating it (see above).

Bimodal particle distributions

The recrystallization behavior of materials containing a wide distribution of particle sizes can be difficult to predict. This is compounded in alloys where the particles are thermally-unstable and may grow or dissolve with time. The situation is more simple in bimodal alloys which have two distinct particle populations. An example is Al-Si alloys where it has been shown that even in the presence of very large (<5 μm) particles the recrystallization behavior is dominated by the small particles (Chan & Humphreys 1984). In such cases the resulting microstructure tends to resemble one from an alloy with only small particles.

See also

References

- RL Barto; LJ Ebert (1971). "Deformation stress state effects on the recrystallization kinetics of molybdenum". Metallugical Transactions. 2 (6): 1643–1649.

- HM Chan; FJ Humphreys (1984). "The recrystallisation of aluminium-silicon alloys containing a bimodal particle distribution". Acta Metallurgica. 32 (2): 235–243. doi:10.1016/0001-6160(84)90052-X.

- RD Doherty (2005). "Primary Recrystallization". In RW Cahn; et al. Encyclopedia of Materials: Science and Technology. Elsevier. pp. 7847–7850.

- RD Doherty; DA Hughes; FJ Humphreys; JJ Jonas; D Juul Jenson; ME Kassner; WE King; TR McNelley; HJ McQueen; AD Rollett (1997). "Current Issues In Recrystallisation: A Review". Materials Science and Engineering. A238: 219–274.

- FJ Humphreys; M Hatherly (2004). Recrystallisation and related annealing phenomena. Elsevier.