Rice Memorial Church, Bangalore

| Rice Memorial Church | |

|---|---|

| London Mission Canarese Chapel, Bangalore | |

| 12°58′16″N 77°34′49″E / 12.971136°N 77.5802331°ECoordinates: 12°58′16″N 77°34′49″E / 12.971136°N 77.5802331°E | |

| Location | Bangalore |

| Country | India |

| Denomination | Church of South India |

| Tradition | Wesleyan |

| History | |

| Former name(s) | Canarese Chapel, Bangalore |

| Consecrated | 27 January 1917 |

| Architecture | |

| Architectural type | Classical European |

| Style | English |

| Years built | 1913-1916 |

| Groundbreaking | 13 November 1913 |

| Completed | 1916 |

| Construction cost | BINR 3500 |

| Administration | |

| Diocese | Karnataka Central Diocese |

| Clergy | |

| Bishop(s) | Rt. Rev. Dr. Prasana Kumar Samuel |

The Rice Memorial Church is located in the busy Avenue Road, Bangalore Pete. It is named after Rev. Benjamin Holt Rice, a missionary of the London Missionary Society (LMS), a Canarese scholar and a pioneer of education in the Bangalore Pete region. The Rice Memorial Church stands on a busy street in the midst of temple, dargahs, book shops and heavy traffic, with its colonial British structure appearing to be out of place in the traditional Bangalore market district. The church stands on the site of the London Mission Canarese Chapel built by Rev. Rice, which itself was built on the site of the first Canarese chapel built by William Campbell in 1834.[1][2][3][4][5] The church is a stone building in the European Classical style, with Tuscan columns, pediments and keystone arch windows. The church building has been demolished and raised at least 3 times, with the current structure consecrated in 1917.[6]

Heritage conservationists have been increasingly urging authorities to include the church, along with other important landmarks on the heritage list, as these monuments are being increasingly threatened by the development of Bangalore City. There has been proposals for widening of Avenue Road, which would result in damage or loss of the Rice Memorial Church and other monuments.[7][8][9] The Rice Memorial is part of the proposed 'Palace-to-Palace' Heritage Corridor (or Golden Corridor), linking Tipu Sultan's Summer Palace (on Albert Victoria Road) to the Bangalore Palace, passing through KR Road, Avenue Road and Palace Road. The corridor proposed by Bangalore's well known architect Naresh Narasimhan, with consultations from Indian National Trust for Art and Cultural Heritage (INTACH) has however has not been accepted by the Government of Karnataka.[10][11]

Benjamin Holt Rice

Benjamin Holt Rice was born in 1814, and attended school till the age of 13. He started working as a clerk in a lawyer's office at the age of 13. Then at 15, he joined his uncle's counting house business. He became drawn towards religion and joined a church at 15, and in 1834 joined the Homerton College at Hackney. Graduating in 1836, he married Jane Peach Singer from Islington, and was appointed as a missionary to South India by the London Missionary Society. Rice joined the Bangalore Mission of the London Missionary Society, which consisted of the Canarese circuit which was considered to be conservative and caste-ridden in the Bangalore Peta area ruled by the Maharaja of Mysore, and the Tamil circuit which was considered to be progressive and the English circuit for the British Officers, both in the Bangalore Cantonment which was under the British Madras Presidency. Within 9 months of his arrival, Rice was able to learn the Canarese language, and starting preaching in that language in the Bangalore Peta region. Rice also mastered the Tamil and also preached in that language.

In 1840, Mrs. Sewell, wife of Rev. James Sewell, opened the first Canarese Girls School for the natives at the Bangalore Peta. It was the first time native girls were able to attend school in this region. Rice prepared the textbooks in Canarese for teaching Geography and Arithmetic. In 1842, Rice and his wife started boarding at the Canarese School. The school still exists today, located on Mission Road (named after the London Mission), Bangalore and is now called the Mitralaya Girls High School . The school was supervised by Jane Rice till her death in 1864, when the school had around 400 girl students.

To impart English education, in 1847, Rice established the Anglo-Vernacular School at Sultanpet, Bangalore, with 100 students. By 1859, there were 397 students, and the school moved into a new building.

In January 1877, a service to commemorate Rice's 50 years of service to the mission in India was celebrated at London Mission Chapel, Infantry Road, Bangalore. A month after that, he died and was buried at the New Cemetery, Hosur Road, Bangalore. During his lifetime, Rice wrote many treatises on Hinduism, Christianity, Indian literature and about India, both in English and Canarese. Rice also translated and composed many Canarese hymns which are still being used today in Kannada churches. He also served in the revision committee for the Canarese Bible for 19 years.

Benjamin Holt Rice is often confused with his son, Benjamin Lewis Rice, a scholar of Canarese, Tamil and Grantha, who complied the 12 volume Epigraphia Carnatica, recording the ancient inscriptions in the Kingdom of Mysore, and the Mysore Gazette.[3][13][14][15][16][17] The works of Benjamin Holt Rice is part of the Rice Papers Collection of the Cambridge University, donated by his son.[18]

Jane Peach Rice, the wife of Benjamin Rice died on 11 March 1864, aged 57 years, and is buried at the Agram Protestant Cemetery in Bangalore. The Agram cemetery also has the graves of Mary Ann Hodson wife of Thomas Hodson of the Wesleyan Missionary Society who died on 10 August 1866 aged 68, Catherine wife of Matthew Trevan Male of the Wesleyan Missionary Society who died on 29 August 1865 aged 49, Fanny Lees child of Catherine and Matthew Male born 29 January 1861 and died 24 April 1861, and Rev. Alexander Maceallum, Missionary of the Free Church of Scotland died 10 June 1862.[19]

Campbell's Petah Chapel, 1834

.jpg)

In 1834, William Campbell of the London Mission raised a chapel on Infantry Road (between St. Andrew's Church and St. Paul's) in the Bangalore Civil and Military Station, incurring a cost of BINR 8000 raised by public subscription, where services were held in Tamil, English and Canarese. In the same year, Campbell obtained land in the main thoroughfare of the Bangalore Petah and a Canarese Chapel was raised and the Canarese services was moved there. The chapel also served as a school and venue for religious discussions with the locals. In 1835, Campbell left for England, leaving the Canarese Chapel in the hands of the native Canarese converts. In 1837, the Canarese chapel was dissolved by Rev. Benjamin Rice and Rev. Colin Campbell, after serious internal conflict within the native congregation on the lines of caste. An inquiry exposed the full scale of the problem, with native converts still adhering to caste hierarchies which was unacceptable to the Mission. In the same year, a regular services re-commenced in the Petah Chapel starting on the occasion of Lord's Day. In 1839, the Petah Chapel was extended to accommodate the growing congregation. In 1845, there was a further extension, and the chapel was also used as an English day school.[21] Due to increase in the size of the congregation, the chapel was razed down to make way for building the new larger Canarese Chapel at the Bangalore Petah.[22]

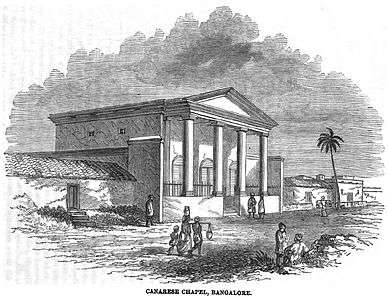

Canarese Chapel, Bangalore, 1851

In 1851, the Canarese Chapel was raised on the grounds where Campbell's chapel stood. The building was much larger than the original chapel and was raised at a cost of BINR 3500 (£350), raised from the proceeds of the sale of the Mission House in Mysore.[21] The opening of the New Canarese Chapel at Bangalore was reported by Rev. Campbell, Rev. Rice and Rev. Sewell and published in the Missionary Magazine and Chronicle of April 1852, along with a sketch. The chapel stood as an impressive European Hall in the midst of native mud houses. The dimensions of the chapel were length of 53 feet, width of 32 feet and height of 20 feet. There was an verandah outside, which served for addressing the natives during weekdays, and vestry attached to the building. There was also an dwelling house for the native teacher and his family. The chapel was consecrated on 19 October 1851, with the opening services commenced by Rev. Rice. Others in[23] attendance included Rev. Daniel Sanderson of the Wesleyan Mission, Rev. James Sewell, Rev C Campbell, many other Europeans and many prominent residents of the Bangalore Petah.[22] In 1907, the Canarese Chapel was deemed as being structurally unsafe and was vacated.[24]

Rice Memorial, 1917

After being deemed as unsafe, the Canerese Chapel was vacated. In 1912, the building plan for the new church was ready, but funding was delayed by the directors of the London Missionary Society. The foundation to the new church was laid on the grounds of the old Canarese Chapel on 13 November 1913 by Mrs. E P Rice and Dr. Horton. However, shortly after that the Bangalore Peta Municipality wanted to widen the Peta (Avenue) Road and wanted 15 ft. of frontage to be maintained. With thew new regulations, it was impossible to build the church. The Municipality offered alternate site for the church, and after persistent negotiations over 2 years, helped acquire the adjoining property, hence making available space for a larger church building. A sum of BINR 3500 was contributed by the native Indians for the building fund. The completed Rice Memorial Church was formally opened by Mrs. Blake, the daughter of Rev. Benjamin Rice on 27 January 1917. A silver key was presented to Mrs. Blake on this occasion. The inauguration service was conducted by Rev. Geo Wilkins. Others in attendance included

- H D Rice, grandson of Rev. Rice

- Rev. Lewis R Scudder, President, South India United Church (SIUC)

- Rev. R A Hickling, President, Canarese Church Council

- Rev. D A Rees, Chairman, Wesleyan Mission in Mysore

- Rev. S Francis, Pastor, SIUC Tamil Church

- Paul Daniel, Pastor, SIUC Canarese Church

- Rev. George Wilkins

- Rev. E H Lewis, Bellary

- Rev. F A Stowell, Bellary

- A W Gunstone

- Rev. A Brough, Chairman, South India District Committee, London Missionary Society

- Rev. W H Throp, Wesleyan Mission

- Rev. G E Phillips

The offertory collected during the inaugural services amounted to 432 Rupees, 5 Annas and 11 Pice[24][27]

Palace-to-Palace Heritage Corridor

The 'Palace-to-Palace' Heritage Corridor was proposed by architect Naresh Narasimhan of Venkataramanan Associates, in consultation by INTACH, to create a heritage zone, protecting old monuments and banning of new modern constructions. The proposed corridor started at the City Institute on Krishna Rajendra Road (KR Road), cutting through Makkala Koota, Tipu Sultan's Summer Palace, Victoria Hospital, Bangalore Fort, entering Avenue Road crossing Rice Memorial, hitting Mysore Bank Circle, continuing on to Palace Road going past Maharani's College, SJI Polytechnic, Central College, Carlton House, KPSC building, stretching till the reservoir, Raj Bhavan, Balabrooie, and Manikyavelu Mansion and ending at Bangalore Palace. Other historic monuments and landmarks to be included in corridor are Mount Carmel College, Bangalore Golf Club, Freedom Park, Bangalore University City Campus, University Law College, Mysore Bank, Historic Centre of Bangalore, Krishna Rajendra Market (KR Market or City Market), St. Luke's Church, Bangalore Medical College and Bangalore Fort High School. However the proposal has not been accepted by the Government of Karnataka.[10][11]

See also

References

- ↑ Rizvi, Aliyeh (27 February 2011). "A Walk Down Avenue Road". A Turquoise Cloud. Retrieved 22 October 2015.

- ↑ Kumar, G S (12 February 2015). "A Parichay with Avenue Rd's heritage" (Bangalore). Times of India. Retrieved 22 October 2015.

- 1 2 "Benjamin Rice". Rices In India: A family devoted to India for 100 years. Retrieved 22 October 2015.

- ↑ Gourley, B. "Daily Photo: Rice Memorial Church". Stories & Movement: The Sum of a Life. Retrieved 22 October 2015.

- ↑ "Earlier known as Doddapete, Avenue Road could be as old as Bengaluru" (Bangalore). The Economic Times. ET Bureau. 26 March 2015. Retrieved 22 October 2015.

- ↑ Rizvi, Aliyeh (13 December 2015). "A gift from the past" (Bangalore). Bangalore Mirror. Bangalore Mirror Bureau. Retrieved 21 December 2015.

- ↑ Srivatsa, Sharath S (25 February 2009). "City's rapid strides have dwarfed its heritage sites" (Bangalore). The Hindu. Retrieved 22 October 2015.

- ↑ "Architects push for heritage zone". Bangalore First. 29 March 2015. Retrieved 22 October 2015.

- ↑ Chamaraj, Kathyaini (23 May 2005). "Protect cultural heritage of Bangalore" (Bangalore). Deccan Herald. Retrieved 22 October 2015.

- 1 2 Kushala, S (27 March 2015). "Time Heritage Corridor was Made a Reality" (Bangalore). Bangalore Mirror. Bangalore Mirror Bureau. Retrieved 23 October 2015.

- 1 2 Bora, Sangeeta (10 September 2015). "Golden Corridor: Bengaluru to have its own heritage zone" (Bangalore). Deccan Chronicle. Retrieved 23 October 2015.

- ↑ Lovett, Richard (1899). The History of the London Missionary Society 1795-1895 (PDF). London: Henry Frowde. p. 113. Retrieved 23 October 2015.

- 1 2 3 Rice, Edward Peter (1890). Benjamin Rice or Fifty years in the Master's Service (PDF). Piccadilly: London Mission Religious Tract Society. p. 192. Retrieved 22 October 2015.

- ↑ Rao, Priyanka S (20 April 2012). "The Rice family legacy: where it all started" (Bangalore). The New Indian Express. Retrieved 22 October 2015.

- ↑ "Benjamin Rice, by his son Edward P. Rice, Bangalore (Religious Tract Society)". The Spectator: 42. 28 June 1890. Retrieved 22 October 2015.

- ↑ Badley, Brenton Hamline (1876). Indian Missionary Directory and Memorial Volume (PDF). Lucknow: American Methodist Mission Press. p. 36. Retrieved 23 October 2015.

- ↑ Chapter XV: Education and Culture, Bangalore District Gazette 1990 (PDF). Government of Karnataka. Retrieved 22 October 2015.

- ↑ "Centre of South Asian Studies: Archive". University of Cambridge. Retrieved 22 October 2015.

- ↑ Johnson, Ronnie. "The Old Protestant Cemetery or Agram Cemetery". Bangalore Walla. Retrieved 19 February 2016.

- ↑ Campbell, William (1839). British India in Its Relation to the Decline of Hindooism, and the Progress of Christianity: Containing Remarks on the Manners, Customs, and Literature of the People. London: John Snow. p. 458. Retrieved 23 October 2015.

- 1 2 Sewell, James (1858). "Bangalore Mission of the London Missionary Society". My library My History Books on Google Play Proceedings of the South India missionary conference, held at Ootacamund, April 19th-May 5th, 1858. Vepery, Madras: SPCK Press. Retrieved 23 October 2015.

- 1 2 3 "Opening of a New Chapel at Bangalore". Missionary Magazine and Chronicle (CXCL). April 1852. Retrieved 23 October 2015.

- 1 2 Slater, T E (September 1898). "Our Missionary Districts: Bangalore". The Chronicle of the London Missionary Society (81): 214–216. Retrieved 23 October 2015.

- 1 2 "Current Mission News: Dedication and Opening of the Rice Memorial Church, Bangalore" (PDF). The Harvest Field. XXXVII (2): 75–77. February 1917. Retrieved 22 October 2015.

- ↑ Hodder, Edwin (1890). Conquests of the Cross, A Record of Missionary Work throughout the World: Vol. 3: Special Edition. London: Cassell and Company Limited. p. 325. Retrieved 23 October 2015.

- ↑ London Missionary Society, ed. (1869). Fruits of Toil in the London Missionary Society. London: John Snow & Co. p. 55. Retrieved 12 September 2016.

- ↑ South India United Church, Rice Memorial Church, Bangalore City : dedication and opening services, January 27th, 28th, 29th and February 4th, 1917. South India United Church. Rice Memorial Church. 1917. Retrieved 23 October 2015.

- ↑ Caine, William Sproston (1890). Picturesque India: A Handbook for European Travellers. London: London and G. Routledge & Sons, Limited. p. 523. ISBN 9781274043993. Retrieved 26 October 2015.

- ↑ "Fort and Pettah of Bangalore". Wesleyan juvenile offering. London: Wesleyan Mission-House. VI. 1849. Retrieved 9 November 2015.

- ↑ Hodson, Richard G (September 1856). "A Bazar, or Shop, in One of the Principal Streets of Bangalore". Wesleyan Juvenile Offering. London: Wesleyan Mission House. XIII. Retrieved 10 November 2015.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Rice Memorial Church, Bangalore. |

._Illustration_for_Conquests_of_the_Cross%2C_A_Record_of_Missionary_Work_throughout_the_World_edited_by_Edwin_Hodder_(Cassell%2C_c_1890).jpg)

.jpg)

_-_Copy.jpg)

_-_Copy.jpg)

_-_Copy.jpg)