Roadside Picnic

| |

| Author | Arkady and Boris Strugatsky |

|---|---|

| Original title | Пикник на обочине |

| Translator | Antonina W. Bouis |

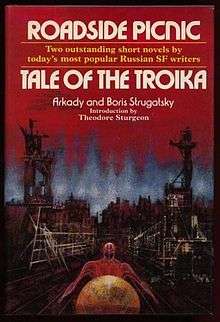

| Cover artist | Richard M. Powers |

| Country | Soviet Union |

| Language | Russian |

| Genre | Science fiction novel |

| Publisher | Macmillan |

Publication date | 1972 |

Published in English | 1977 |

| Media type | Print (Hardcover) |

| ISBN | 0-02-615170-7 |

| OCLC | 2910972 |

Roadside Picnic (Russian: Пикник на обочине, Piknik na obochine, IPA: [pʲɪkˈnʲik nɐ ɐˈbotɕɪnʲe]) is a short science fiction novel written by Arkady and Boris Strugatsky in 1971. By 1998, 38 editions of the novel were published in 20 countries.[1] The novel was first translated to English by Antonina W. Bouis. The preface to the first American edition of the novel (MacMillan Publishing Co., Inc, New York, 1977) was written by Theodore Sturgeon. The film Stalker, directed by Andrei Tarkovsky, is loosely based on the novel, with a screenplay written by the Strugatsky brothers.

Book title

Roadside Picnic is a work of fiction based on the aftermath of an extraterrestrial event (called the Visitation) that simultaneously took place in half a dozen separate locations around Earth for a two-day period. Neither the Visitors themselves nor their means of arrival or departure were ever seen by the local population who lived inside the relatively small (a few square kilometers) area of each of the six Visitation Zones. Such zones exhibit strange and dangerous phenomena not understood by humans, and contain artifacts with inexplicable, seemingly supernatural properties. The name of the novel derives from an analogy proposed by the character Dr. Valentine Pilman who compares the extraterrestrial event to a picnic:

A picnic. Picture a forest, a country road, a meadow. Cars drive off the country road into the meadow, a group of young people get out carrying bottles, baskets of food, transistor radios, and cameras. They light fires, pitch tents, turn on the music. In the morning they leave. The animals, birds, and insects that watched in horror through the long night creep out from their hiding places. And what do they see? Old spark plugs and old filters strewn around... Rags, burnt-out bulbs, and a monkey wrench left behind... And of course, the usual mess—apple cores, candy wrappers, charred remains of the campfire, cans, bottles, somebody’s handkerchief, somebody’s penknife, torn newspapers, coins, faded flowers picked in another meadow.[2]

In this analogy, the nervous animals are the humans who venture forth after the Visitors left, discovering items and anomalies that are ordinary to those who discarded them, but incomprehensible or deadly to those who find them.

This explanation implies that the Visitors may not have paid any attention to or even noticed the human inhabitants of the planet during their "visit" just as humans do not notice or pay attention to grasshoppers or ladybugs during a picnic. The artifacts and phenomena left behind by the Visitors in the Zones were garbage, discarded and forgotten without any preconceived intergalactic plan to advance or damage humanity. There is little chance that the Visitors will return again because for them it was a brief stop for reasons unknown on the way to their actual destination.

Plot

Background

The novel is set in a post-visitation world where there are now six Zones known on Earth (each zone is approximately five square miles/kilometers in size) that are full of unexplained phenomena and where strange happenings have briefly occurred, assumed to have been visitations by aliens. World governments and the UN try to keep tight control over them to prevent leakage of artifacts from the Zones, fearful of unforeseen consequences. A subculture of stalkers – thieves who go into the Zones to steal the artifacts for profit – evolves around the Zones.

The novel is set in and around a specific Zone in Harmont, a fictitious town in Canada, and follows the main protagonist over an eight-year period.

Introduction

The introduction is a live radio interview with Dr. Pilman who is credited with the discovery that the six Visitation Zones' locations weren't random. He explains it so: "Imagine that you spin a huge globe and you start firing bullets into it. The bullet holes would lie on the surface in a smooth curve. The whole point (is that) all six Visitation Zones are situated on the surface of our planet as though someone had taken six shots at Earth from a pistol located somewhere along the Earth–Deneb line. Deneb is the alpha star in Cygnus."

Section 1

The story revolves around Redrick "Red" Schuhart, a tough and experienced stalker who regularly enters the Zone illegally at night in search of valuable artifacts for profit. Trying to clean up his act, he becomes employed as a lab assistant at the International Institute, which studies the Zone. To help the career of his boss, whom he considers a friend, he goes into the Zone with him on an official expedition to recover a unique artifact (a full "empty"), which leads to his friend's death later on.

This comes as a great shock when the news reaches Redrick, drunk in a bar, and he blames himself for his friend's fate. While Redrick is at the bar, a police force enters looking for stalkers. Redrick is forced to use an "itcher" to make a hasty getaway.

Red's girlfriend Guta is pregnant and decides to keep the baby no matter what. It is widely rumored that incursions into the Zone by stalkers carry high risk of mutations in their children, even though no radiation or other mutagens had been detected in the area. They decide to marry.

Section 2

Disillusioned Redrick returns to stalking. In the course of his joint expedition into the Zone with a fellow stalker named Burbridge The Vulture, the latter steps into a substance known as "hell slime," which slowly dissolves his leg bones. Amputation must be urgently performed to avoid certain death. Redrick pulls Burbridge out of the Zone and drops him off at a surgeon, avoiding the patrols. Later on Redrick is confronted by Burbridge's daughter, who gets angry at him for saving her father.

Guta has given birth to a happy and intelligent daughter, fully normal but for having short, light full body hair and black eyes. They lovingly call her "Monkey."

Redrick meets with his clients in a posh hotel, selling them a fresh portion of the Zone artifacts, but what they are really after is "hell slime". It's hinted that they want it for military research. Redrick claims he doesn't have it yet and leaves. Shortly afterward Redrick is arrested, but escapes. He then contacts his clients, telling them where he hid the "slime" sample that he had smuggled out previously. Redrick insists that all the proceeds from the sale be sent to Guta. He realizes that the "slime" will be used for some kind of weapon of mass destruction, but decides he has to provide for his family. He then gives himself up to the police.

Section 3

Redrick's old friend Richard Noonan (a supply contractor with offices inside the Institute), is revealed as a covert operative of an unnamed, presumably governmental, secret organization working to stop the contraband outflow of artifacts from the Zone. Believing that he's nearing the successful completion of his multi-year assignment, he is confronted and scolded by his boss, who reveals to him that the flow is stronger than ever, and is tasked with finding who is responsible and how they operate.

It is revealed that the stalkers are now organized under the cover of the "weekend picnics-for-tourists" business set up by Burbridge. They jokingly refer to the setup as "Sunday school". Noonan meets with Dr. Valentine Pilman for lunch and they have an in-depth discussion of the Visitation and humanity in general. This is where the idea of "Visitation as a roadside picnic" is articulated.

Redrick is home again, having served his time. Burbridge visits him regularly, trying to entice him into some secret project, but Redrick declines. Guta is depressed because their daughter has nearly lost her humanity and ability to speak, resembling a monkey more and more. Redrick's dead father has come home from the cemetery inside the Zone, as other very slowly-moving (and completely harmless) reanimated dead are now returning to their homes all around town. They are usually destroyed as soon as they are discovered. Together Redrick's father and daughter symbolize the complete inhumanity of the Zone.

Section 4

Redrick goes into the Zone one last time in order to reach the wish-granting "Golden Sphere". He has a map, given to him by Burbridge, whose son Arthur joins him on the expedition. Redrick knows one of them has to die in order to deactivate a phenomenon known as "meatgrinder" in order for the other to reach the sphere, but he keeps this a secret from his companion.

After they get to the location, surviving many obstacles, the young man rushes towards the sphere shouting out his wishes only to be savagely dispatched by the meatgrinder. Spent and exhausted, Redrick looks back on his whole life, hoping it wasn't all just garbage, that he still has the old spark in his soul that he remembers having as a child, hoping the Sphere will find something good in his heart – presumably it decides what is one's true wish by itself – and in the end can't think of anything else other than repeating the now dead youngster's crying words: "HAPPINESS FOR EVERYBODY, FREE, AND LET NO ONE BE LEFT BEHIND!".

Artifacts left by Visitors in the Zones

The artifacts left behind by the Visitors can be broken down into five categories:

- 1) Objects beneficial to humans, yet whose original purpose, how precisely they work, or how to manufacture them is not understood. The 'So-So' and 'Bracelets' are among the artifacts that fall into this category.

- 2) Objects whose function, original purpose, or how to use them to benefit humans cannot yet be understood. The 'Black Sprays' and 'Needles' are among the artifacts that fall into this category.

- 3) Bizarre materials and effects within the zone that are largely unexplained and highly hazardous. "The Witch's Jelly"/"Hell Slime", "Cotton", "graviconcentrates" (areas of anomalous gravity), and other hazards to moving through the Zone are examples of this type.

- 4) Objects that are unique and never seen by scientists. Their existence is passed along as legends by Stalkers and their function is so dangerous and so far beyond human comprehension that they are better off left undisturbed. The 'Golden Sphere' and the 'Jolly Ghost' are among the artifacts that fall into this category.

- 5) Not objects but effects on people who were present inside the Zones during the Visitation. Humans who survived the Visitation without going blind (apparently from a loud noise) or being infected by the plague caused unexplained problems if they emigrated away. A barber who survived the Visitation emigrated to a far-off city and within a year 90 percent of his customers died in mysterious circumstances; a number of natural disasters foreign to the area (typhoons, tornadoes) struck the city as well. Even people who were never present during the Visitation but frequently visit the Zone are changed somehow, for example by having mutated children or by having duplicates of their dead relatives return to their homes.

Origins and Soviet censorship

The story was written by the Strugatsky brothers in 1971 (the first outlines written January 18–27, 1971 in Leningrad, with the final version completed between October 28 and November 3, 1971 in Komarovo.) It was first published in the Avrora literary magazine in 1972, issues 7–10. Parts of it were published in the Library of Modern Science Fiction book series, vol. 25, 1973. It was also printed in the newspaper Youth of Estonia in 1977–1978.

In 1977, the novel was first published in the United States in English.

Roadside Picnic was refused publication in book form in the Soviet Union for eight years due to government censorship and numerous delays. The heavily censored versions published between 1980 and 1990 significantly departed from the original version written by the authors.[3] The Russian-language versions endorsed by the Strugatsky brothers as the original were published in the 1990s.

Awards and nominations

- The novel was nominated for a John W. Campbell Award for best science fiction novel of 1978 and won second place.[4]

- In 1978 the Strugatskys were accepted as honorary members of the Mark Twain Society for their "outstanding contribution to world science fiction literature."[5]

- A 1979 Scandinavian congress on science fiction literature awarded the Swedish translation the Jules Verne prize for best novel of the year published in Swedish.

- In 1981 at the sixth festival of science fiction literature in Metz the novel won the award for best foreign book of the year.

Adaptations and cultural influence

- A 1979 science fiction film, Stalker, directed by Andrei Tarkovsky, with a screenplay written by Boris and Arkady Strugatsky, is loosely based on the novel.

- While not a direct adaptation, the video game series S.T.A.L.K.E.R. is heavily influenced by Roadside Picnic. The first game in the series, "S.T.A.L.K.E.R.: Shadow of Chernobyl", references many important plot points from the book, such as the wish granter and the unknown force blocking the path to the center of the zone. It also contains elements such as anomalies and artifacts that are similar to those described in the book, but that are created by a supernatural ecological disaster, not by alien visitors. A few characters are also very similar to those in books.

- The book is referenced in the post-apocalyptic video game Metro 2033. A character shuffles through a shelf of books in a ruined library and finds Roadside Picnic. He states that it is "something familiar". Metro 2033 was created by individuals who had worked on S.T.A.L.K.E.R. before founding their own video game development company, and both the developers of the game and the author of the book it was adapted from were inspired by Roadside Picnic and by the "stalker" subculture it spawned.

- In 2003, the Finnish theater company Circus Maximus produced a stage version of Roadside Picnic, called Stalker. Authorship of the play was credited to the Strugatskys and to Mikko Viljanen and Mikko Kanninen.[6]

- A tabletop roleplaying game in 2012 called Stalker was developed by Ville Vuorela of Burger Games with the permission of Boris Strugatsky. The game was originally released in 2008 in Finnish by the same author.

- A Finnish low-budget indie film Vyöhyke (Zone), directed by Esa Luttinen, was released in 2012. The film is set in a Finnish visitation zone, and refers to material in the novel as well as the Tarkovsky film.[7][8]

- British progressive rock band Guapo's 2013 album "History Of The Visitation", is based on the novel.

- The podcast TANIS from Pacific Northwest Stories makes reference to the book in episode 5 of season 2.

- A 2016 American TV series directed by Alan Taylor.

Translation

English releases

- Strugatsky, Arkady and Boris. Roadside Picnic / Tale of the Troika (Best of Soviet Science Fiction) translated by Antonina W. Bouis. New York: Macmillan Pub Co, 1977, 245 pp. ISBN 0-02-615170-7. LCCN: 77000543.

- Strugatsky, Arkady and Boris. Roadside Picnic. London: Gollancz, April 13, 1978, 150 pp. ISBN 0-575-02445-3.

- Strugatsky, Arkady and Boris. Roadside Picnic / Tale of the Troika. New York: Pocket Books, February 1, 1978. ISBN 0-671-81976-3.

- Strugatsky, Arkady and Boris. Roadside Picnic. London: Penguin Books, September 27, 1979, 160 pp. ISBN 0-14-005135-X.

- Strugatsky, Arkady and Boris. Roadside Picnic. New York: Pocket Books (Timescape), September 1, 1982, 156 pp. ISBN 0-671-45842-6.

- Strugatsky, Arkady and Boris. Roadside Picnic (SF Collector's Edition). London: Gollancz, August 24, 2000, 145 pp. ISBN 0-575-07053-6.

- Strugatsky, Arkady and Boris. Roadside Picnic (S.F. Masterworks). London: Gollancz, February 8, 2007. ISBN 0-575-07978-9.

- Strugatsky, Arkady and Boris. Roadside Picnic. Translated by Olena Bormashenko, foreword by Ursula K. Le Guin, afterword by Boris Strugatsky. Chicago: Chicago Review Press, May 1, 2012. ISBN 978-1-61374-341-6.

Errata

English translations of Roadside Picnic from 1977 on, through the years mistakenly had Section 0 taking place at year 30 after Visitation, instead of 13 in the original, which "has baffled essayists for decades".[9]

In the 2012 translation, in the introduction, the references to the time of the visit now correctly refer to "thirteenth anniversary", etc.[10]

References

- ↑ СТРУГАЦКИЙ АРКАДИЙ НАТАНОВИЧ (28.08.1925–12.10.1991) Life and Work of Arkady and Boris Strugatsky (in Russian)

- ↑ Atkady and Boris Strugatsky, Roadside Picnic, English ed., 1977

- ↑ (Russian) Борис Стругацкий: Комментарии к пройденному, 1998, section ПИКНИК НА ОБОЧИНЕ

- ↑ Roadside Picnic | Science Fiction & Fantasy Books | WWEnd. Worldswithoutend.com. Retrieved on 2011-03-17.

- ↑ Sci-fi writers brothers Strugatsky: Awards. Rusf.ru (1977-09-11). Retrieved on 2011-03-17.

- ↑ "Circus Maximus in English". 2013-02-18. Retrieved 2013-02-18.

- ↑ "Vyöhyke – Zone, the movie". Retrieved 13 May 2013.

- ↑ "Vyöhyke (2012)". IMDb. Retrieved 13 May 2013.

- ↑ Andre-Driussi, Michael (January 2012). "A Roadside Picnic Triptych". The New York Review of Science Fiction. Pleasantville, NY: Dragon Press. 24 (5): 20–22.

- ↑ Arkady and Boris Strugatsky (2012). Roadside Picnic. Chicago, IL: Chicago Review Press, Incorporated.

External links

- Roadside Picnic, full text (Antonina W. Bouis translation)

- Roadside Picnic, parallel text in Russian and English.

- Review of the Roadside Picnic on the Infinity Plus website.

- The SF Site Featured Review: Roadside Picnic

- Stanislaw Lem about the Strugatskys' Roadside Picnic

- Audio review and discussion of Roadside Picnic at The Science Fiction Book Review Podcast