Robert Love Taylor

| Robert Love Taylor | |

|---|---|

| |

| 24th Governor of Tennessee | |

|

In office January 17, 1887 – January 19, 1891 | |

| Preceded by | William B. Bate |

| Succeeded by | John P. Buchanan |

|

In office January 21, 1897 – January 16, 1899 | |

| Preceded by | Peter Turney |

| Succeeded by | Benton McMillin |

| United States Senator from Tennessee | |

|

In office March 4, 1907 – March 31, 1912 | |

| Preceded by | Edward W. Carmack |

| Succeeded by | Newell Sanders |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Tennessee's 1st district | |

|

In office March 4, 1879 – March 3, 1881 | |

| Preceded by | James H. Randolph |

| Succeeded by | Augustus H. Pettibone |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

July 31, 1850 Carter County, Tennessee |

| Died |

March 31, 1912 (aged 61) Washington, D.C. |

| Resting place |

Monte Vista Memorial Park Johnson City, Tennessee[1] |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse(s) |

Sarah Baird Alice Hill Mamie St. John |

| Relations |

Nathaniel Green Taylor (father) Alfred A. Taylor (brother) Landon Carter Haynes (uncle) Nathaniel Edwin Harris (cousin) |

| Profession | Attorney, lecturer, editor |

| Signature |

|

Robert Love "Bob" Taylor (July 31, 1850 – March 31, 1912) was an American politician, writer, and lecturer. He served as Governor of Tennessee from 1887 to 1891, and again from 1897 to 1899, and subsequently served as a United States Senator from 1907 until his death. He also represented Tennessee's 1st district in the United States House of Representatives from 1879 to 1881, the last Democrat to hold that district's house seat.[2]

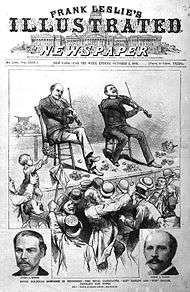

A charismatic speaker, Taylor is remembered for defeating his older brother, Alfred A. "Alf" Taylor, in the 1886 gubernatorial campaign known as "The War of the Roses." [3] This campaign involved storytelling, fiddle-playing, and practical jokes, standing in contrast to the state's previous gubernatorial campaigns, which typically involved fierce rhetoric and personal attacks.[2] Though Robert Taylor won, Alfred Taylor would serve as governor in the early 1920s.

Along with politics, Taylor was a public lecturer and magazine editor. He published several collections of his lectures and short stories in the 1890s and early 1900s, and was co-editor of the Taylor-Trotwood Magazine.

Early life and career

Taylor was born in Happy Valley in Carter County, Tennessee, the third son of Nathaniel Green Taylor, a Methodist minister, and Emmaline Haynes, an accomplished pianist.[4]:23 His father, a member of the Whig Party, had been defeated by Andrew Johnson in a campaign for Congress in 1849, but would win the seat in the mid-1850s. His mother's family supported the Democratic Party, and her brother, Landon Carter Haynes, was a prominent Democratic politician. Robert Taylor would adopt his mother's political leanings and become a Democrat, while his older brother, Alfred, would follow his father into the Whig (and later Republican) Party.[3]

Nathaniel Taylor supported the Union during the Civil War,[4]:19 and the family moved to Philadelphia in 1861 when the Confederate Army occupied East Tennessee. In 1864, the Taylor brothers enrolled in Pennington Seminary in New Jersey.[5] The family moved to Washington in 1867 when Nathaniel Taylor was appointed Commissioner of Indian Affairs by President Andrew Johnson, and Robert Taylor took a position in the Treasury Department.[4]:29 The family returned to Tennessee in 1869, where Robert would attend Buffalo Institute (modern Milligan College) and East Tennessee Wesleyan College.[5] While at the former, he cowrote a play with his brother, Alfred.[4]:29

During the 1870s, Robert Taylor tried several business ventures, including farming, operating a lumber mill, and managing his father's Doe River iron forge. He largely failed at all of these, however, as he was reckless with money, overpaid his employees, and preferred conversation and storytelling to working.[4]:35 He read law during this period with S.J. Kirkpatrick in Jonesborough.[5]

In 1878, Alfred Taylor ran for the Republican nomination for the 1st district congressional seat against Augustus H. Pettibone. At the party's convention, Alfred appeared to have more delegates, but Pettibone managed to win the nomination, leading Taylor's supporters to suspect corruption. Robert Taylor was then convinced to run against Pettibone on the Democratic ticket in the general election. The public got its first real taste of his speaking ability at a debate in Bristol, when Taylor thrashed Pettibone with a "bewildering kaleidoscope of oratory."[4]:40 With help from Alfred's disgruntled supporters, Robert was able to edge Pettibone for the seat by 750 votes.[4]:44 Among the legislation sponsored by Taylor was a bill calling for a federal income tax.[2]

Taylor was defeated by Pettibone in his reelection campaign in 1880, and lost to Pettibone a third time when he tried to regain the seat in 1882.[4]:45 He then launched a pro-Democratic Party newspaper, The Comet, in nearby Johnson City.[4]:46 In 1884, Taylor was named the elector from the 1st district for Democratic presidential candidate Grover Cleveland, and campaigned across the district against the Republican elector, Samuel Hawkins. After Cleveland won the election, he appointed Taylor federal pension agent in Knoxville.[4]:48

Governor

In 1886, Republicans, hoping to exploit divisions in the Democratic Party between the pro-farmer and Bourbon factions, nominated Alfred Taylor for governor. Democrats, realizing they needed a unifier and effective campaigner to counter Alfred, nominated Robert Taylor as their candidate, pitting the two brothers against one another. The Prohibition Party offered its nomination to the Taylors' father, Nathaniel, but he declined.[4]:50

The 1886 gubernatorial campaign is remembered for the Taylor brothers' relatively light-hearted political banter and entertaining speeches. Canvassing together, they spent the first part of each campaign stop "cussing out each other's politics" and telling stories, and the second part playing fiddle tunes while the crowd danced.[4]:8 At a stop in Madisonville, Robert suggested both he and Alfred were roses, but he was a white rose while Alfred was a red rose. As their respective supporters subsequently wore white and red roses, the campaign became known as the "War of the Roses" (the name also hearkened to the 15th-century English conflict). Their campaign stops drew massive crowds, ranging from around 6,000 in smaller towns to 25,000 in Nashville.[4]:50 In a record turnout on election day, Robert edged Alfred by 16,000 votes.[2]

Although Taylor was uncomfortable with the criticism and attacks that came with the executive office, he managed to enact tax reform and educational reform. He was assailed for issuing too many pardons, and demanded the state build a reformatory for juveniles. When he didn't get it, he issued a pardon to virtually every juvenile who sought one.[3] In 1888, an angry Bourbon faction sought to thwart his nomination for reelection, but was unsuccessful. He won the general election later that year, with 156,799 votes to 139,014 for the Republican candidate, Samuel Hawkins, and 6,893 for the Prohibition candidate, J.C. Johnson.[2]

In 1889, Taylor signed into law a poll tax and a number of other bills aimed at suppressing turnout among African-American and poor voters.[3] A number of prohibition laws were also repealed.[2] Suffering from ill health and disenchanted by divisions within his own party, he did not seek reelection in 1890.[2]

In the early 1890s, Taylor, struggling with debt from constant campaigning, asked his brother, Alfred (who was now a Congressman), for advice. Alfred suggested Robert go on a lecture tour, and invited Robert's family to move in with his family until he got his finances in order. Robert opened his tour on December 29, 1891, at Jobe's Hall in Johnson City, where he presented his lecture, "The Fiddle and the Bow," with an admission price of 50 cents per person.[4] After Alfred left Congress, he joined Robert on tour, and the two cowrote and presented "Yankee Doodle and Dixie." The tour was a major financial success, netting the brothers tens of thousands of dollars.[4]:64–67

In 1896, the Democratic Party was again concerned about Republican chances of winning the governor's office, as the incumbent, Peter Turney, had won the office using questionable tactics two years earlier. When several Democratic leaders invited Taylor to run, he reluctantly agreed, and defeated Turney for the party's nomination in August 1896.[2] After a fierce general election campaign, he edged the Republican candidate, George Tillman, with about 49% of the vote to Tillman's 47%.[2] Republicans suggested voting irregularities had helped Taylor win, but the Democratic-dominated state legislature obstructed any attempt at an investigation.[2]

The most notable event of Taylor's second stint in office was the Tennessee Centennial, which marked the 100th anniversary of the state's admission to the Union. The centennial was celebrated with the Tennessee Centennial and International Exposition, a five-month world's fair held in Nashville's Centennial Park in 1897, with Taylor making numerous appearances.[4]:70

Later life

After his final term as governor, Taylor returned to the lecture circuit, though he continuously sought one of the state's U.S. Senate seats. In 1907, he defeated the incumbent senator, Edward W. Carmack, in a public primary, and was elected by the state legislature to the seat later that year.[2] He served from 1907 until his death in 1912. Among the legislation he supported was the Sixteenth Amendment, which allowed the federal government to levy income taxes. He helped secure the amendment's passage in the Senate in 1909.[2]

In 1910, when incumbent Democratic governor Malcolm R. Patterson withdrew from the state's gubernatorial contest due to the turmoil created within the party over the Prohibition issue, Taylor agreed to serve as a replacement nominee. He lost in the general election, however, to the Republican nominee, Ben W. Hooper. Hooper had defeated Taylor's brother, Alfred, for the Republican nomination earlier that year.[2]

On March 31, 1912, Taylor suffered a gallstone attack, and died following unsuccessful surgery at Providence Hospital in Washington. A specially-chartered train carried his body to Nashville, where it lay in the capitol for several days. It was then taken to Knoxville, where a funeral procession of over 40,000 people– the largest in the city's history– attended his burial at Old Gray Cemetery.[6] In 1938, he was reburied at Monte Vista Cemetery in Johnson City in a family plot adjacent to his brother, Alfred.[1]

Family

Taylor's great-grandfather, General Nathaniel Taylor (1771–1816), served during the War of 1812.[4]:17 Another great-grandfather, Landon Carter (1760–1800), was a Revolutionary War veteran for whom Carter County was named.[7] Taylor's father, Nathaniel Green Taylor (1819–1887), served two terms in Congress (1853–1855 and 1866–1867), and published poetry and religious essays.[4]:18 Taylor's brother, Alfred, served three terms in the U.S. House of Representatives (1889–1895), and one term as Governor of Tennessee (1921–1923). Nathaniel Edwin Harris, who served as Governor of Georgia from 1915 to 1917, was a first cousin of Taylor.

Taylor married Sarah Baird in 1878, and they had five children.[2] After she died in 1900, he married Alice Hill. This second marriage ended in divorce after a few years. Taylor was married for a third time to Mamie St. John in 1904.[2]

Works

- Gov. Bob Taylor's Tales (1896)

- Echoes: Centennial and Other Notable Speeches, Lectures and Stories (1899)

- Lectures and Best Literary Productions of Bob Taylor (1900)

- Life Pictures (1907)

See also

References

- 1 2 Robert Love Taylor at Find a Grave

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Phillip Langsdon, Tennessee: A Political History (Franklin, Tenn.: Hillsboro Press, 2000), pp. 213-228.

- 1 2 3 4 Robert L. Taylor, Jr., "Robert L. Taylor," Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture, 2009. Retrieved: 8 November 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Paul Deresco Augsburg, Bob and Alf Taylor: Their Lives and Lectures (Morristown, Tenn.: Morristown Book Company, 1925).

- 1 2 3 Governor Robert Love Taylor Papers, 1887-1891 (finding aid), Tennessee State Library and Archives, 1965. Retrieved: 10 November 2012.

- ↑ Jack Neely, The Marble City: A Photographic Tour of Knoxville's Graveyards (Knoxville, Tenn.: University of Tennessee Press, 1999), p. 15.

- ↑ W. Calvin Dickinson, "Landon Carter," Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture. Retrieved: 6 February 2014.

Further reading

- Taylor, Robert L., Jr. "Apprenticeship in the First District: Bob and Alf Taylor’s Early Congressional Races." Tennessee Historical Quarterly 28 (Spring 1969): 24-41.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Robert Love Taylor. |

- Life and career of Senator Robert Love Taylor (Our Bob) published 1913, hosted by the Portal to Texas History.

- "Robert Love Taylor of Tennessee"

- Works by Robert Love Taylor at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Robert Love Taylor at Internet Archive

- "Albert and Martha King". --- photo of Martha King, illegitimate child of Robert Love Taylor.

| United States House of Representatives | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by James Henry Randolph |

Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Tennessee's 1st congressional district 1879–1881 |

Succeeded by Augustus Herman Pettibone |

| Political offices | ||

| Preceded by William B. Bate |

Governor of Tennessee 1887–1891 |

Succeeded by John P. Buchanan |

| Preceded by Peter Turney |

Governor of Tennessee 1897–1899 |

Succeeded by Benton McMillin |

| United States Senate | ||

| Preceded by Edward W. Carmack |

U.S. Senator (Class 2) from Tennessee 1907–1911 Served alongside: James B. Frazier, Luke Lea |

Succeeded by Newell Sanders |

| Tennessee's delegation(s) to the 60th–62nd United States Congresses (ordered by seniority) | ||

|---|---|---|

| 60th | Senate: J. Frazier, Sr. • R. Taylor | House: W. Brownlow • J. Gaines • J. Moon • T. Sims • L. Padgett • F. Garrett • N. Hale • W. Houston • G. Gordon • C. Hull |

| 61st | Senate: J. Frazier Sr. • R. Taylor | House: W. Brownlow† • J. Moon • T. Sims • L. Padgett • F. Garrett • W. Houston • G. Gordon • C. Hull • J. Byrns Sr. • R. Austin • Z. Massey‡ †Brownlow died in Jul. 1910; ‡Massey elected in Nov. 1910 |

| 62nd | Senate: R. Taylor† • L. Lea • N. Sanders‡ • W. Webb§ †Taylor died in Mar. 1912; ‡Sanders appointed to fill vacancy; §Webb elected to fill vacancy |

House: J. Moon • T. Sims • L. Padgett • F. Garrett • W. Houston • G. Gordon† • C. Hull • J. Byrns Sr. • R. Austin • S. Sells • K. McKellar‡ †Gordon died in Aug. 1911; ‡McKellar elected in Dec. 1911 |