Robert Wight

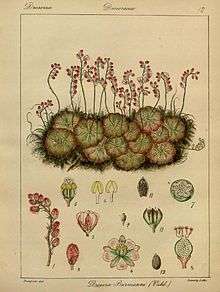

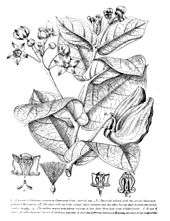

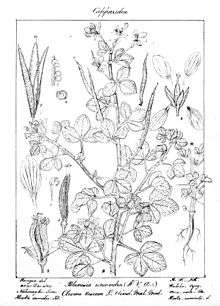

Robert Wight (6 July 1796 – 26 May 1872) was a Scottish surgeon and botanist who spent 30 years in India. He studied botany in Edinburgh under John Hope. He was the director of the Botanic Garden in Madras. He made use of local artists to make illustrations of the plants around him. He learned the art of lithography and used it to publish the Icones Plantarum Indiae Orientalis (Illustrations of the plants of Eastern India) in six volumes in 1856. He spent the time between 1819-1853 in India and devoted most of that time to the study of plants.[1][2][3][4]

Life and work

Early life

Robert was the son of a Writer to the Signet in Edinburgh and was born at Milton, East Lothian, Scotland. He was the twelfth among fourteen siblings. He was educated at the Edinburgh High School and professionally at Edinburgh University, where he took a surgeon's diploma in 1816.[3] He worked as a ship's surgeon for two years and went on a few voyages, including one to the USA.[5][6]

Early work in India

He went to India in 1819 as the first assistant surgeon in the 42nd Native Infantry (which was later commanded by his brother Colonel James Wight) in the East India Company's service. His interest in botany was clear and within three years he was transferred to Madras and made in charge of the Botanic Gardens and in 1826 he was appointed as naturalist to the East India Company to succeed Dr Shuter.[6] He made extensive collections from southern India from 1826 to 1828, and sent them to Sir William Hooker at Glasgow. This collection consisted of specimens from around Madras up to Vellore and from Samalkota and Rajahmundry, now in Andhra Pradesh. Earlier, a collection that he had shipped to Robert Graham was lost at sea. He also improved his collection through his association with local collectors.[5] In 1828 the government discontinued his position at the Botanic Gardens and reassigned him to regimental duties as garrison surgeon at Nagapattinam.[3] He continued his study of flora in and around Tanjore for two years. He was promoted to the full rank of a surgeon in 1831.[5]

Return to Scotland

He took a three-year sick leave in 1831 and took to Scotland, 100,000 specimens from India consisting of 3000-4000 species. The luggage weighed 2 tons. These specimens were studied and used by Dr. George Arnott Walker-Arnott, Professor of Botany at the University of Glasgow. Wight also published the Spicilegium Neilgherrense in two volumes with 200 coloured plates. Between 1840 and 1850, he issued another two volume work named Illustrations of Indian Botany, the object of which was to give figures and fuller descriptions of some of the chief species described in a systematic book of the highest botanical merit, which he prepared along with Dr. Walker-Arnott, and which was published under the title Prodromus Florae Peninsulae Indicae. He distributed a lithographic catalogue consisting of 2403 species from his collections among several leading botanical authorities in Europe, most of them enumerated in his work, Prodromus.[5]

Return to India

Wight returned to India in 1834 as a full surgeon in the 33rd Regiment of Native Infantry at Bellary. During this period he began working on the medicinal plants of India, maintaining native botanical artists and publishing brief notes in the Madras Journal of Literature and Science.[7] In 1836 he moved into the revenue department to examine the cultivation of tobacco, senna and cotton. He worked at the experimental farm in Coimbatore between 1841 and 1850.[6]

Wight was interested in making a large illustrated work on Indian plants based on Sowerby's English botany. Wight's illustrations were chiefly by native artists, with as many as twenty of them working at his home. His favourite artists where Rungiah (Rungia) and Govindoo who produced most of the plates for his six volumes of Icones Plantarum Indiae Orientalis. Unlike other British workers of the time, he gave credit to his native artists and even named a genus of Orchid, Govindooia (now Tropidia), after Govindoo. This was the first attempt at a flora for India in which the natural system of classification was followed. This work was however not completed.[3]

He founded the Madras Agri-Horticultural Society and contributed a lot of articles to the Madras Journal of Literature and Science in the form of short letters and full articles on botany and related subjects between 1835-1840. He published several articles on cotton which were consolidated in an article in the Garderns Chronicle in 1861. He helped in the editing of Pharmacopoiea of India by Edward John Waring where he added observations on medicinal properties of herbs and some botanical information. In 1836, he took up the responsibility of the Peradeniya collections at the botanical gardens in Sri Lanka following his contact with GW Walker.[5]

Many botanists from other parts of India depended on Wight and Gardener, especially McClelland who needed this support after the death of Griffith for continuing the Calcutta Journal of Natural History. He also argued for retaining the entire collection of dried plants belonging to Griffith in Calcutta at the botanical gardens there for the benefit of Indian naturalists in the future.[5]

Return to England and collections

Wight left India after retiring from service in March 1853. He returned to England with poor health and difficulty in hearing. He bought the estate of Grazeley Lodge near Reading and pursued agriculture. His final post was at Coimbatore, where he was in charge of an experimental cotton farm. He donated his entire botanical collection from India, consisting of nearly 4000 species to Kew herbarium. This collection includes the type specimens of his new descriptions. In his lifetime, Wight described many genera and over 3000 species of plants. Of these, in the later seminal work on flora of India by Hooker, 40 new genera and over 500 species were recognised. Many others were synonymised. His collections are at many leading museums of the world. While most are at Kew, some important ones are at Geneva, Paris, Leningrad and Glasgow. Some duplicates are still retained in herbaria in Calcutta, Dehradun and Madras in India.

Wight was diagnosed with sympoms of an illnes in April 1869 and he died on 26 May 1872 at Grazeley Lodge. Wight was married to Rosa Harriet, the third daughter of Lacey Gray Ford of the Madras Medical Board in 1838 and he was survived by his wife, four sons and a daughter.[6][8]

Recognition

He was elected as a Fellow of the Linnaean Society and member of the Imperial Academy in 1832 and Fellow of Royal Society in 1855.[5] He was a member of several learned societies in India at the time. He was in constant touch with several leading botanists and scientists of his time including Arnott, Brown, Delessert,[6] Griffith, Hooker, Lindley, Martius, Munro, Nees, Royle and Wallich. In recognition of his valuable contributions to Botany, several taxa are named after him. Wallich dedicated the genus Wightia to him. Hooker recorded about 122 Indian plants named by various botanists to commemorate Wight.

Plants named after Wight

- Aerva wightii Hook. f.

- Agrostis wightii Nees

- Anaphalis wightiana DC.

- Anaphyllum wightii Schott

- Andrographis wightiana Arnott

- Andropogon wightianus Steudel

- Anisochilus wightii Hook. f.

- Anotis wightiana Hook. f.

- Apocopis wightii Nees

- Arenga wightii Griffith

- Arisaema wightii Schott

- Arundinaria wightiana Nees

- Beilschmiedia wightii Benth.

- Blumea wightiana DC.

- Calophyllum wightianum Wall.

- Carex wightiana Nees

- Celtis wightii Planch.

- Ceropegia wightii Grah.

- Chloris wightiana Nees

- Cinnamomum wightii Meissn.

- Cirrhopetalum wightii Thwaite.

...and others

Variants include Wt.[10] and R.W.[11] Some of his early contributions carry his name as "Richard Wight" inadvertently.[5]

References

- ↑ Wight, Robert (1853). Icones plantarum Indiae orientalis; or, Figures of Indian plants By Robert Wight. Item notes: v.6 (Original from Harvard University, Digitized 22 May 2007 ed.). Madras: P.R. Hunt American Mission Press.

- ↑ Noltie, H. J. (1999) Indian botanical drawings 1793-1868 from the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh. Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh. Edinburgh.

- 1 2 3 4 Noltie, H. J. (2005) Robert Wight and the Illustration of Indian Botany. The Hooker Lecture. The Linnean. Special Issue No 6.

- ↑ Noltie, H. J. (2007) The Life and Work of Robert Wight. (Book 1), Botanical Drawings by Rungiah & Govindoo: the Wight Collection (Book 2) Journeys in Search of Robert Wight (Book 3) ISBN 978-1-906129-02-6

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Basak, RK (November 1981). "Robert Wight and His Botanical Studies in India". Taxon. 30 (4): 784–793. doi:10.2307/1220080.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Obituary notices". Proceedings of the Linnean Society of London: xliv–xlvii. 1873.

- ↑ Wight, Robert (1835). "Observations on Mudar (Calotropis procera), with some remarks on the medical properties of the natural order Asclepiadeae". Madras Journal of Literature and Science. 2: 70–85.

- ↑ Anon. (1838). "Births, Marriages and Deaths". The Asiatic Journal and Monthly Miscellany. 26: 112.

- ↑ IPNI. Wight.

- ↑ R.P. Sharma (1968). The Indian forester: Volume 94, Issues 1-6, p. 45

- ↑ Wight, Robert (1840). Illustrations of Indian botany: or figures illustrative of each of the natural orders of Indian plants, described in the author's prodromus florae peninsulae Indiae orientalis. J. B. Pharoah

Other sources

- Curtis' Botanical Magazine. 1931. Dedications and Portraits 1827-1927. Compiled by Earnest Nelmes and Wm. Cuthbertson .London: Bernard Quaritch Ltd.

- Gardener's Chronicle. 1872. The Late Dr. Robert Wight , F.R.S. vol. 50, no. 22.

- Gray, Asa. 1873. Scientific Papers. American Journal of Science and Arts 5, ser. 3.

- King Sir George. 1899. The Early History of Indian botany. Journal of Botany 37, no. 443.

External links

- Robert Wight's work on orchids

- Contributions to the botany of India

- Basak R. K., Taxon, Vol. 30, No. 4 (Nov., 1981), pp. 784–793, International Association for Plant Taxonomy (IAPT), Robert Wight and His Botanical Studies in India, p.784

- Scanned works of Robert Wight