Robinia pseudoacacia

| Black locust | |

|---|---|

| | |

| Flowers | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| (unranked): | Angiosperms |

| (unranked): | Eudicots |

| (unranked): | Rosids |

| Order: | Fabales |

| Family: | Fabaceae |

| Subfamily: | Faboideae |

| Tribe: | Robinieae |

| Genus: | Robinia |

| Species: | R. pseudoacacia |

| Binomial name | |

| Robinia pseudoacacia L. | |

| |

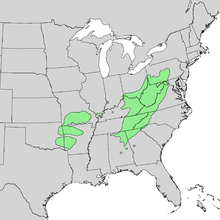

| Natural range | |

Robinia pseudoacacia, commonly known in its native territory as black locust,[1] is a medium-sized deciduous tree native to the southeastern United States, but it has been widely planted and naturalized elsewhere in temperate North America, Europe, Southern Africa[2] and Asia and is considered an invasive species in some areas.[3] Another common name is false acacia,[4] a literal translation of the specific name (pseudo meaning fake or false and acacia referring to the genus of plants with the same name.) It was introduced into Britain in 1636.[5]

History and naming

The name 'locust' is said to have been given to Robinia by Jesuit missionaries, who fancied that this was the tree that supported St. John in the wilderness, but it is native only to North America. The locust tree of Spain (Ceratonia siliqua or carob tree), which is also native to Syria and the entire Mediterranean basin, is supposed to be the true locust of the New Testament.

Robinia is now a North American genus, but traces of it are found in the Eocene and Miocene rocks of Europe.[6]

Distribution and invasive habit

The black locust is native to the eastern United States, but the exact native range is not accurately known[7] as the tree has been cultivated and is currently found across the continent, in all the lower 48 states, eastern Canada, and British Columbia.[1] The native range is thought to be 2 separate populations, one centered about the Appalachian Mountains, from Pennsylvania to northern Georgia, and a second westward focused around the Ozark Plateau and Ouachita Mountains of Arkansas, Oklahoma and Missouri.

Black locust's current range has been expanded by humans distributing the tree for landscaping and now includes: Australia, Canada, China, Europe, India, Northern and South Africa, temperate regions in Asia, New Zealand, Southern South America.[8]

Black locust is an interesting example of how one plant can be considered an invasive species even on the same continent it is native to. For example, within the western United States, New England region, and in the Midwest, black locust is considered an invasive species. In the prairie and savanna regions of the Midwest black locust can dominate and shade open habitats.[9] These ecosystems have been decreasing in size and black locust is contributing to this, when black locust invades an area it will convert the grassland ecosystem into a forested ecosystem where the grasses are displaced.[10] Black locust has been listed as invasive in Connecticut and prohibited in Massachusetts.[1]

In Australia black locust has become naturalized within Victoria, New South Wales, South, and Western Australia. It is considered an environmental weed there.[8] In South Africa, it is regarded as a weed because of its habit suckering.[11]

Description

Black locust reaches a typical height of 40–100 feet (12–30 m) with a diameter of 2–4 feet (0.61–1.22 m).[12] Exceptionally, it may grow up to 52 metres (171 ft) tall[13] and 1.6 metres (5.2 ft) diameter in very old trees. It is a very upright tree with a straight trunk and narrow crown which grows scraggly with age.[5] The dark blue-green compound leaves with a contrasting lighter underside give this tree a beautiful appearance in the wind and contribute to its grace.

Black locust is a shade intolerant species[7] and therefore is typical of young woodlands disturbed areas where sunlight is plentiful and soil is dry, in this sense, black locust can often grow as a weed tree. It also often spreads by underground shoots or suckers which contribute to the weedy character of this species.[5] Young trees are often spiny, however, mature trees often lack spines. In the early summer black locust flowers; the flowers are large and appear in large, intensely fragrant (reminiscent of orange blossoms), clusters. The leaflets fold together in wet weather and at night (nyctinasty) as some change of position at night is a habit of the entire leguminous family.

Although similar in general appearance to the honey locust, it lacks that tree’s characteristic long branched thorns on the trunk, instead having the pairs of short prickles at the base of each leaf; the leaflets are also much broader then honey locust. It may also resemble Styphnolobium japonicum which has smaller flower spikes and lacks spines.

Detailed description

- The bark is dark gray brown and tinged with red or orange in the grooves. It is deeply furrowed into grooves and ridges which run up and down the trunk and often cross and form diamond shapes.[5]

- The roots of black locust contain nodules which allow it to fix nitrogen as is common within the pea family.

- The branches are typically zig-zagy and may have ridges and grooves or may be round.[5] When young, they are at first coated with white silvery down, this soon disappears and they become pale green and afterward reddish or greenish brown.

- Prickles may or may not be present on young trees, root suckers, and branches near the ground; typically, branches high above the ground rarely contain prickles. R. pseudoacacia is quite variable in the quantity and amount of prickles present as some trees are densely prickly and other trees have no prickles at all. The prickles typically remain on the tree until the young thin bark to which they are attached is replaced by the thicker mature bark. They develop from stipules[14] (small leaf like structures which grow at the base of leaves) and since stipules are paired at the base of leaves, the prickles will be paired at the bases of leaves. They range from .25–.8 inches (0.64–2.03 cm) in length and are somewhat triangular with a flared base and sharp point. Their color is of a dark purple and they adhere only to the bark.[14]

- Wood: Pale yellowish brown; heavy, hard, strong, close-grained and very durable in contact with the ground. The wood has a specific gravity of 0.7333, and a weight of approximately 45.7 pounds per cubic foot.

- The leaves are compound, meaning that each leaf contains many smaller leaf like structures called leaflets, the leaflets are roughly paired on either side of the stem which runs through the leaf (rachis) and there is typically one leaflet at the tip of the leaf (odd pinnate). The leaves are alternately arranged on the stem. Each leaf is 6–14 inches (15–36 cm) long and contains 9-19 leaflets, each being 1–2 inches (2.5–5.1 cm)long, and .25–.75 inches (0.64–1.91 cm) wide. The leaflets are rounded or slightly indented at the tip and typically rounded at the base. The leaves come out of the bud folded in half, yellow green, covered with silvery down which soon disappears. Each leaflet initially has a minute stipel, which quickly falls, and is connected to the (rachis) by a short stem or petiolule. The leaves are attached to the branch with slender hairy petioles which is grooved and swollen at the base. The stipules are linear, downy, membranous at first and occasionally develop into prickles. The leaves appear relatively late in spring.

- The leaf color of the fully grown leaves is a dull dark green above and paler beneath. In the fall the leaves turn a clear pale yellow.

- The flowers open in May or June for 7–10 days, after the leaves have developed. They are arranged in loose drooping clumps (racemes) which are typically 4–8 inches (10–20 cm) long.[5] The flowers themselves are cream-white (rarely pink or purple) with a pale yellow blotch in the center and imperfectly papilionaceous in shape. They are about 1 inch (2.5 cm) wide, very fragrant, and produce large amounts of nectar. Each flower is perfect, having both stamens and a pistil (male and female parts). There are 10 stamens enclosed within the petals; these are fused together in a diadelphous configuration, where the filaments of 9 are all joined to form a tube and one stamen is separate and above the joined stamens. The single ovary is superior and contains several ovules. Below each flower is a calyx which looks like leafy tube between the flower and the stem. It is made from fused sepals and is dark green and may be blotched with red. The pedicels (stems which connect the flower to the branch) are slender, .5 inches (1.3 cm), dark red or reddish green.

- The fruit is a typical legume fruit, being a flat and smooth pea-like pod 2–4 inches (5.1–10.2 cm) long and .5 inches (1.3 cm) broad. The fruit usually contains 4-8 seeds.[5] The seeds are dark orange brown with irregular markings. They ripen late in autumn and hang on the branches until early spring.[6] There are typically 25500 seeds per pound.[15]

- Winter buds: Minute, naked (having no scales covering them), three or four together, protected in a depression by a scale-like covering lined on the inner surface with a thick coat of tomentum and opening in early spring. When the buds are forming they are covered by the swollen base of the petiole.

- Cotyledons are oval in shape and fleshy.

Reproduction and dispersal

Black locust produces both sexually via flowers, and asexually via root suckers. The flowers are pollinated by insects, primarily by Hymenopteran insects. The physical construction of the flower separates the male and female parts so that self-pollination will not typically occur.[16] The seedlings grow rapidly but they have a thick seed coat which means that not all seeds will germinate. The seed coat can be weakened via hot water, sulfuric acid, or be mechanically scarified and this will allow a greater quantity of the seeds to grow.[5][15] The seeds are produced in good crops every year or every-other year.

Root suckers are an important method of local reproduction of this tree. The roots may grow suckers after damage (by being hit with a lawn mower or otherwise damaged) or after no damage at all. The suckers are stems which grow from the roots, directly into the air and may grow into full trees. The main trunk also has the capability to grow sprouts and will do so after being cut down.[12] This makes removal of black locust difficult as the suckers need to be continually removed from both the trunk and roots or the tree will regrow. This is considered an asexual form or reproduction.

The suckers allow black locust to grow into colonies which are often exclude other species. These colonies may form dense thickets which shade out competition.[17] Black locust has been found to have either 2n=20 or 2n=22 chromosomes.

Human mediated dispersal

Black locust has been spread and used as a plant for erosion control as it is fast growing and generally a tough tree.[15] The wood, considered the most durable wood in America, has been very desirable and motivated people to move the tree to areas where it is not native so the wood can be farmed and used.

Ecology

When growing in sandy areas this plant can enrich the soil by means of its nitrogen-fixing nodules, allowing other species to move in.[12] On sandy soils black locust may also often replace other vegetation which cannot fix nitrogen.[15]

Black locust is a typical early successional plant, a pioneer species, it grows best in bright sunlight and does not handle shade well.[7] It specializes in colonizing disturbed and edges of woodlots before it is eventually replaced with more shade tolerant species. It prefers dry to moist limestone soils but will grow on most soils as long as they are not wet or poorly drained.[7] This tree tolerates a soil pH range of 4.6 to 8.2.[15] Within its native range it will often grow on soils of Inceptisols, Ultisols, and Alfisols groups. Black locust does not do well on compacted, clayey or eroded soils. Black locust is a part of the Appalachian mixed mesophytic forests.

Black locust is not a particularly valuable plant for wildlife, but does provide valuable cover when planted on previously open areas. Its seeds are also eaten by bobwhite quail and other game birds and squirrels. Woodpeckers may also nest in the trunk since older trees are often infected by heart rot.

Pests

Locust leaf miner Odontota dorsalis attacks the tree in spring and turns the leaves brown by mid summer, it slows the growth of the tree but not seriously.[15] The locust borer Megacyllene robiniae larvae carve tunnels into the trunk of the tree and make it more prone to being knocked down by the wind. Heart rot is the only significant disease affecting black locust.[15] Black locust is also attacked by Chlorogenus robiniae, a virus which causes witch's broom growths, clear leaflet veins are a symptom of the disease.[18]

Uses

Cultivation

Black locust is a major honey plant in the eastern US, and has been planted in European countries. In many European countries, it is the source of the renowned acacia honey. Flowering starts after 140 growing degree days. However, its blooming period is short (about 10 days) and it does not consistently produce a honey crop year after year. Weather conditions can have quite an effect on the amount of nectar collected, as well; in Ohio for example, good locust honey flow happens in one of five years.[19]

It can be easily propagated from roots, softwood, or hardwood[5][15] and this allows for easy reproduction of the plant. Cultivars may also be grafted as this ensures the parent and daughter plant will be genetically identical.

R. pseudoacacia is considered an excellent plant for growing in highly disturbed areas as an erosion control plant.[15] The roots are shallow aggressive which help to hold onto soil and the tree grows quickly and on poor soils due to its ability to fix nitrogen.

Black locust has nitrogen-fixing bacteria on its root system, so it can grow on poor soils and is an early colonizer of disturbed areas. With fertilizer prices rising, the importance of black locust as a nitrogen-fixing species is also noteworthy. The mass application of fertilizers in agriculture and forestry is increasingly expensive; therefore nitrogen-fixing tree and shrub species are gaining importance in managed forestry.[20]

It is also planted for firewood because it grows rapidly, is highly resilient in a variety of soils, and it grows back even faster from its stump after harvest by using the existing root system.[21] (see coppicing)

In Europe, it is often planted along streets and in parks, especially in large cities, because it tolerates pollution well.

Cultivars

Several cultivars exist but 'Frisia' seems to be one of the most planted ones.

- 'Decaisneana' has been considered a cultivar but is more accurately a hybrid (R. psudeoacacia x R. viscosa). It has light rose-pink colored flowers and small or no prickles.[22]

- ‘Frisia’, a selection with bright yellow-green leaves and red prickles, is occasionally planted as an ornamental tree.[5]

- 'Purple robe' has dark rose-pink flowers and bronze red new growth. The flowers tend to last longer than on the wild tree.[5]

- 'Tortuosa', a small tree with curved and distorted branches.[5][23]

- 'Unifoliola', a plant with fewer leaflets, no prickles, and a shorter height.

Wood

The wood is extremely hard, being one of the hardest woods in Northern America. It is very resistant to rot, and durable, making it prized for furniture, flooring, paneling, fence posts, and small watercraft. Wet, newly cut planks have an offensive odor which disappears with seasoning. Black locust is still in use in some rustic handrail systems. In the Netherlands and some other parts of Europe, black locust is one of the most rot-resistant local trees, and projects have started to limit the use of tropical wood by promoting this tree and creating plantations. Flavonoids in the heartwood allow the wood to last over 100 years in soil.[24] As a young man, Abraham Lincoln spent much of his time splitting rails and fence posts from black locust logs.

Black locust is highly valued as firewood for wood-burning stoves; it burns slowly, with little visible flame or smoke, and has a higher heat content than any other species that grows widely in the Eastern United States, comparable to the heat content of anthracite.[25] For best results, it should be seasoned like any other hardwood, but black locust is also popular because of its ability to burn even when wet.[20] In fireplaces, it can be less satisfactory because knots and beetle damage make the wood prone to “spitting” coals for distances of up to several feet. If the black locust is cut, split, and cured while relatively young (within 10 years), thus minimizing beetle damage, “spitting” problems are minimal.

In 1900, the value of Robinia pseudoacacia was reported to be practically destroyed in nearly all parts of the United States beyond the mountain forests which are its home by locust borers which riddle the trunk and branches. Were it not for these insects, it would be one of the most valuable timber trees that could be planted in the northern and middle states. Young trees grow quickly and vigorously for a number of years, but soon become stunted and diseased, and rarely live long enough to attain any commercial value.[6]

Food and Medicine

In traditional medicine of India, different parts of R. pseudoacacia are used as laxative, antispasmodic, and diuretic.[26]

In Romania the flowers are sometimes used to produce a sweet and perfumed jam. This means manual harvesting of flowers, eliminating the seeds and boiling the petals with sugar, in certain proportions, to obtain a light sweet and delicate perfume jam.

Although the bark and leaves are toxic, various reports suggest that the seeds and the young pods of the black locust are edible. Shelled seeds are safe to harvest from summer through fall, and are edible both raw and/or boiled.[27] Due to the small nature of the seeds, shelling them efficiently can prove tedious and difficult. In France and in Italy, R. pseudoacacia flowers are eaten as beignets after being coated in batter and fried in oil;[28] they are also eaten in Japan, largely as tempura.[29][30]

Toxicity

The bark, leaves, and wood are toxic to both humans and livestock.[31] Important constituents of the plant are the toxalbumin robin, which loses its toxicity when heated, and robinin, a nontoxic glucoside.[32]

Horses that consume the plant show signs of anorexia, depression, incontinence, colic, weakness, and cardiac arrhythmia. Symptoms usually occur about 1 hour following consumption, and immediate veterinary attention is required.

Flavonoids content

Black locust leaves contain flavone glycosides characterised by spectroscopic and chemical methods as the 7-O-β-d-glucuronopyranosyl-(1 → 2)[α-l-rhamnopyranosyl-(1 → 6)]-β-d-glucopyranosides of acacetin (5,7-dihydroxy-4′-methoxyflavone), apigenin (5,7,4′-trihydroxyflavone), diosmetin (5,7,3′-trihydroxy-4′-methoxyflavone) and luteolin (5,7,3′,4′-tetrahydroxyflavone).[33]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 "Robinia pseudoacacia". Natural Resources Conservation Service PLANTS Database. USDA. Retrieved 22 October 2015.

- ↑ http://www.biodiversityexplorer.org/plants/fabaceae/robinia_pseudoacacia.htm

- ↑ "Robinia pseudoacacia". County-level distribution map from the North American Plant Atlas (NAPA). Biota of North America Program (BONAP). 2013.

- ↑ "BSBI List 2007" (xls). Botanical Society of Britain and Ireland. Retrieved 2014-10-17.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Dirr, Michael A (1990). Manual of woody landscape plants. (4. ed., rev. ed.). Champaign, Illinois: Stipes Publishing Company. ISBN 0-87563-344-7.

- 1 2 3 Keeler, Harriet L. (1900). Our Native Trees and How to Identify Them. New York: Charles Scriber's Sons. pp. 97–102.

- 1 2 3 4 Huntley, J. C. (1990). "Robinia pseudoacacia". In Burns, Russell M.; Honkala, Barbara H. Hardwoods. Silvics of North America. Washington, D.C.: United States Forest Service (USFS), United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). 2. Retrieved 14 July 2016 – via Northeastern Area State and Private Forestry (www.na.fs.fed.us).

- 1 2 "Robinia pseudoacacia". keyserver.lucidcentral.org. Retrieved 2016-07-14.

- ↑ "black locust: Robinia pseudoacacia (Fabales: Fabaceae (Leguminosae)): Invasive Plant Atlas of the United States". www.invasiveplantatlas.org. Retrieved 2016-07-14.

- ↑ "PCA Alien Plant Working Group – Black Locust (Robinia pseudoacacia)". www.nps.gov. Retrieved 2016-07-14.

- ↑ http://www.arc.agric.za/home.asp?pid=1031

- 1 2 3 "Robinia pseudoacacia". www.eddmaps.org. Retrieved 14 July 2016.

- ↑ "New tuliptree height record". Eastern Native Tree Society. Retrieved 2008-09-22.

- 1 2 "Robinia pseudoacacia". Flora of China. Missouri Botanical Garden. Retrieved 14 July 2016 – via eFloras.org.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 "Robinia psudeoacacia factsheet" (PDF). USDA. Retrieved 14 July 2016.

- ↑ Houser, Cameron (August 2014). "GENETICALLY MEDIATED LEAF CHEMISTRY IN INVASIVE AND NATIVE BLACK LOCUST (ROBINIA PSEUDOACACIA L.) ECOSYSTEMS" (PDF). Retrieved 2016-07-15.

- ↑ "Black locust invasive species control" (PDF). Michigan DNR. Retrieved 14 July 2016.

- ↑ Internationally dangerous forest tree diseases, Issues 911-940. USDA. 1963.

- ↑ http://www.beeclass.com/DTS/blacklocust.htm

- 1 2 "UN Food & Agriculture Organization's notes on Black Locust".

- ↑ "OSU: Managing Your Woodlot for Firewood" (PDF).

- ↑ "Ornamental Cultivar Details". www.flemings.com.au. Retrieved 14 July 2016.

- ↑ "Robinia pseudoacacia 'Tortuosa' – Plant Finder". www.missouribotanicalgarden.org. Retrieved 14 July 2016.

- ↑ "Black Locust: A Multi-purpose Tree Species for Temperate Climates". Retrieved 2007-06-27.

- ↑ "Heating the Home with Wood" (PDF).

- ↑ Wang L, Waltenberger B, Pferschy-Wenzig EM, Blunder M, Liu X, Malainer C, Blazevic T, Schwaiger S, Rollinger JM, Heiss EH, Schuster D, Kopp B, Bauer R, Stuppner H, Dirsch VM, Atanasov AG. Natural product agonists of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ): a review. Biochem Pharmacol. 2014 Jul 29. pii: S0006-2952(14)00424-9. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2014.07.018. PubMed PMID 25083916.

- ↑ Thayer, Samuel (2006). The Forager's Harvest. W5066 State Hwy 86 Ogema, WI 54459: Forager's Harvest. p. 251. ISBN 0-9766266-0-8.

- ↑ http://www.cuisine-campagne.com/index.php?post/2007/05/07/250-beignets-de-fleurs-d-acacia

- ↑ ja:ニセアカシア

- ↑ http://cookpad.com/recipe/3179033

- ↑ "Toxicity of Black Locust". www.woodweb.com. Retrieved 5 July 2016.

- ↑ Medicinal and Poisonous Plants of Southern and Eastern Africa – Watt and Brandwijk

- ↑ Nigel C. Veitch, Peter C. Elliott, Geoffrey C. Kite & Gwilym P. Lewis (2010). "Flavonoid glycosides of the black locust tree, Robinia pseudoacacia (Leguminosae)". Phytochemistry. 71 (4): 479–486. doi:10.1016/j.phytochem.2009.10.024. PMID 19948349.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Black locust. |

- Purdue University

- Robinia pseudoacacia images at bioimages.vanderbilt.edu

- Robinia pseudoacacia images at Forestry Images

- Robinia pseudoacacia – US Forest Service Fire Effects Database

- Robinia pseudoacacia at USDA Plants Database

- Black locust – US Forest Service Silvics Manual

- Black Locust (as an invasive species)

- Interactive Distribution Map of Robinia pseudoacacia

- Robinia pseudoacacia flowers as food

- Black locust – Invasive species: Minnesota DNR

- EUFORGEN species page on Robinia pseudoacacia. Information, genetic conservation units and related resources.