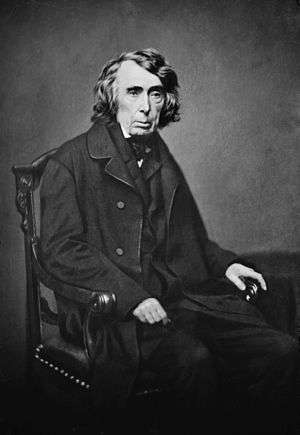

Roger B. Taney

| Roger Taney | |

|---|---|

| |

| 5th Chief Justice of the United States | |

|

In office March 15, 1836 – October 12, 1864 | |

| Nominated by | Andrew Jackson |

| Preceded by | John Marshall |

| Succeeded by | Salmon Chase |

| 12th United States Secretary of the Treasury | |

|

In office September 23, 1833 – June 25, 1834 | |

| President | Andrew Jackson |

| Preceded by | William Duane |

| Succeeded by | Levi Woodbury |

| 11th United States Attorney General | |

|

In office July 20, 1831 – November 14, 1833 | |

| President | Andrew Jackson |

| Preceded by | John Berrien |

| Succeeded by | Benjamin Butler |

| United States Secretary of War Acting | |

|

In office June 18, 1831 – August 1, 1831 | |

| President | Andrew Jackson |

| Preceded by | John Eaton |

| Succeeded by | Lewis Cass |

| Attorney General of Maryland | |

|

In office September 1827 – June 18, 1831 | |

| Governor |

Joseph Kent Daniel Martin Thomas Carroll Daniel Martin |

| Preceded by | Thomas Kell |

| Succeeded by | Josiah Bayly |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Roger Brooke Taney March 17, 1777 Calvert County, Maryland, U.S. |

| Died |

October 12, 1864 (aged 87) Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Political party |

Federalist (Before 1828) Democratic (1828–1864) |

| Spouse(s) | Anne Key |

| Alma mater | Dickinson College |

| Religion | Roman Catholicism |

| Signature |

|

Roger Brooke Taney (/ˈtɔːni/; March 17, 1777 – October 12, 1864) was the fifth Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, holding that office from 1836 until his death in 1864. He is most remembered for delivering the majority opinion in Dred Scott v. Sandford (1857), that ruled, among other things, that African-Americans, having been considered inferior at the time the Constitution was drafted, were not part of the original community of citizens and, whether free or slave, could not be considered citizens of the United States, which created an uproar among abolitionists and the free states of the northern U.S. He is also notable as the first Roman Catholic (and first non-Protestant) appointed both to a presidential cabinet, as Attorney General under President Andrew Jackson, as well as to the Court.

Taney, a Jacksonian Democrat, was made Chief Justice by Jackson.[upper-alpha 1] Taney was a believer in states' rights but also the Union, a slaveholder who manumitted his slaves.[2] He believed that power and liberty were extremely important and if power became too concentrated, then it posed a grave threat to individual liberty. He opposed attempts by the national government to regulate or control matters that would restrict the rights of individuals. From Prince Frederick, Maryland, he had practiced law and politics simultaneously and succeeded in both. After abandoning the Federalist Party as a losing cause, he rose to the top of the state's Jacksonian machine. As Attorney General (1831–1833) and then Secretary of the Treasury (1833–1834), and as a prominent member of the Kitchen Cabinet, Taney became one of Jackson's closest advisers, assisting Jackson in his populist crusade against the powerful Bank of the United States.

In Dred Scott v. Sandford, an African-American slave named Dred Scott had appealed to the Supreme Court in hopes of being granted his freedom based on his having been brought by his masters to live in free territories. The Taney Court ruled that persons of African descent could not be, nor were ever intended to be, citizens under the U.S. Constitution, and thus the plaintiff (Scott) was without legal standing to file a suit. The framers of the Constitution, Taney famously wrote, believed that blacks "had no rights which the white man was bound to respect; and that the negro might justly and lawfully be reduced to slavery for his benefit. He was bought and sold and treated as an ordinary article of merchandise and traffic, whenever profit could be made by it."[3] The court also declared the Missouri Compromise (1820) unconstitutional, thus permitting slavery in all of the country's territories. Taney died during the final months of the American Civil War on the same day that his home state of Maryland abolished slavery.

Early life and career

Roger Brooke Taney was born on March 17, 1777 in Calvert County, Maryland, the son of Monica (Brooke) and Michael Taney.[4] He was the second son, and the third of seven children (four sons and three daughters) born to a slaveholding family of tobacco planters in Calvert County, Maryland. He received a rudimentary education from a series of private tutors. After instructing him for a year, his last tutor, David English, recommended that Taney was ready for college.[5] At the age of 15 he entered Dickinson College in Pennsylvania, graduating with honors in 1795.[6] As a younger son with no prospect of inheriting the family plantation, Taney chose the profession of law. He read law and in 1799 was admitted to the bar. He quickly distinguished himself as one of Maryland's most promising young lawyers.

Marriage and family

Taney married Anne Phoebe Charlton Key, sister of Francis Scott Key, on January 7, 1806.[7] They had seven children together.

Career

In 1799, the same year he began practicing as an attorney, Taney was elected to the Maryland State Legislature, where he served one term as a Federalist. Returning to private practice, he served as a director of the State Bank Branch in Frederick, Maryland, from 1810 to 1815.

He was elected a state senator in 1816, serving until 1821—this time as a Democratic Republican, because the Federalist party had dissolved. He was also a director of the Frederick County Bank from 1818 to 1823, when he returned to private practice. When the 1824 presidential election divided the party between supporters and opponents of Andrew Jackson, Taney became a staunch Jacksonian Democrat. He was elected Attorney General of Maryland in 1827, but resigned in 1831, first to serve as acting United States Secretary of War, and then to accept President Jackson's nomination as Attorney General of the United States.

Jackson Administration

.jpg)

Among Taney's opinions as attorney general, two revealed his stand on slavery: one supported South Carolina's law prohibiting free blacks from entering the state, and one argued that blacks could not be citizens. In 1833, as secretary of the Treasury, Taney ordered an end to the deposit of Federal money in the Second Bank of the United States, an act that killed the institution. Jacksonian populists believed the bank was run for the benefit of wealthy coastal elites and acted detrimentally to the interests of poorer western and southern farmers.

Treasury nomination

Taney was the first nominee to the United States Executive Cabinet to be rejected by the United States Senate when his recess appointment as Secretary of the Treasury failed in a vote of 28–18.[8] Rather than return to the position of Attorney General, however, Taney returned to Maryland and resumed private practice.

Supreme Court nominations

In January 1835 Jackson, in defiance of the Senate's rejection of Taney as Treasury Secretary, nominated Taney as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court to replace the retiring Gabriel Duvall. The Senate was scheduled to vote on Taney's confirmation on the closing day of the session that month, but the anti-Jackson Whigs who dominated the Senate blocked the vote and introduced a motion to abolish the open seat on the Court. The latter was unsuccessful, but the Whigs succeeded in preventing Taney's confirmation to the Court. (The seat was then left open for over a year until Philip Pendleton Barbour was confirmed to it in 1836.)

Two factors intervened to help Taney onto the Court, however: after the 1834 elections, Jacksonian Democrats controlled the Senate and, during the 1835 recess, Chief Justice John Marshall died. On December 28, 1835, Jackson sent the nomination of Taney as Chief Justice to the Senate, which had convened that month; after a long and bitter battle with considerable opposition from Whig leaders Henry Clay, Daniel Webster, and Jackson's former Vice President John C. Calhoun, Taney was confirmed on March 15, 1836, and received his commission the same day.

The Taney Court, 1836–1864

Unlike Marshall, who had supported a broad role for the federal government in the area of economic regulation, Taney and the other justices appointed by Jackson more often favored the power of the states. In a series of Commerce Clause cases exemplified by Mayor of the City of New York v. Miln (1837), wherein the challenged New York statute required masters of incoming ships to report information on all passengers they brought into the country, i.e. age, health, last legal residence, etc. The question before the Taney court was whether or not the state statute undercut Congress's authority to regulate commerce; or was it a police measure, as New York claimed, fully within the authority of the state. Taney and his colleagues sought to devise a more nuanced means of accommodating competing federal and state claims of regulatory power. The Court ruled in favor of New York.

The Taney Court also presided over the case of slaves who had taken over the Spanish schooner Amistad. Fellow Justice Joseph Story wrote the Court's decision and opinion. Taney sided with Story's opinion but left no written record of his own in regard to the Amistad case.

Taney's famous opinion in Charles River Bridge v. Warren Bridge (1837), denied a Contract Clause challenge to the state-authorized construction of a free bridge to compete with an existing toll bridge under a prior charter. The Charles River Bridge was opened in 1786 and it replaced a Harvard-operated ferry service between Boston and Charlestown. The bridge paid for its construction and operating expenses, and turned a profit for its investors, by charging a toll. In 1828, Massachusetts authorized a second toll bridge between Boston and Charlestown, known as the Warren Bridge. The new bridge was to be just 300 feet upstream from the Charles River Bridge, and planned to be toll-free after six years of operation. Harvard College, which originally protested the new bridge, was to be paid half the annuity owed by the Charles River Bridge proprietors. During and after construction of the new Warren Bridge, the owners of the Charles River Bridge claimed the state had granted them an implied monopoly on the bridge. The case went all the way to the United States Supreme Court in 1831, but was not ultimately decided for six years. The opinion struck a balance between the need for change in the face of technological innovation and the importance of stability to encourage investments. Taney preferred to narrowly construe any rights granted by the states in favor of a broad reservation of power for the state to regulate property in ways suited to preserve the public's interest. "The object and end of all government is to promote happiness and prosperity of the community by which it is establish, and it can never be assumed that the government intended to diminish its power of accomplishing the end for which it was created."[9] If all such charters carried with them exclusive rights, government would significantly curtail its power to govern—to promote the public interest.

Although the original toll bridge company claimed that its corporate charter impliedly conferred monopoly status that the state could not abridge, Taney declared that a corporate charter should be strictly construed to encompass only express guarantees, not implied privileges. He declared that the public interest was the overriding concern in this case, and so allowed the Warren Bridge to operate. "While the rights of private property are sacredly guarded, we must not forget that the community also has right, and that the happiness and well-being of every citizen depends on their faithful preservation."[9] Taney worried that allowing the Charles River Bridge's charter to stand would block progress and internal improvements. The case has had profound importance in shaping judicial authority over property rights, corporations, charters and issues of equal access to economic development. By ruling this way, Taney placed the Court on the side of economic development and technological advancement. Taney rejected the notion of an implied monopoly and his opinion was very Jacksonian in tone in respect to the opposition to monopoly power. This case laid the first real foundation for the police power of the states. Marshall, in the Dartmouth College Case had said that a charter of the state was a contract that could no more be broken than could the contract of an individual. The implications of this would greatly have hampered the state's police power. Taney held that the charter was a contract but being one of the state it must be construed strictly. Since it said nothing about not building another bridge it could be assumed that in providing for the well being of the people, the state had reserved that right. This was the first of several of the Chief Justice's decisions that built up the police power of the state.

In Briscoe v. Commonwealth Bank of Kentucky (1837), the third critical ruling of Taney's debut term, the Chief Justice confronted the banking system, in particular state banking. Disgruntled creditors had demanded invalidation of the notes issued by Kentucky's Commonwealth Bank, created during the panic of 1819 to aid economic recovery. The institution had been backed by the credit of the state treasury and the value of unsold public lands, and by every usual measure, its notes were bills of credit of the sort prohibited by the federal Constitution. Briscoe demanded that purveyors of rag paper be forced to pay debts in sound paper or precious metal, as contracts most often stipulated. Kentucky officials contended that their debtor bank, had not issued bills of credit of the sort prohibited by the Constitution because the institution had been granted a separate corporate identity by legislative charter. Surely the framers had in mind banning only notes issued directly by treasuries or land offices.

Briscoe v. Bank of Kentucky manifested this change in the field of banking and currency in the first full term of the court's new chief justice. Article I, section 10 of the Constitution prohibited states from using bills of credit, but the precise meaning of a bill of credit remained unclear. In the 1830 case, Craig v. Missouri, the Marshall Court had held, by a vote of 4 to 3, that state interest-bearing loan certificates were unconstitutional. However, in the Briscoe case, the Court upheld the issuance of circulating notes by a state-chartered bank even when the Bank's stock, funds, and profits belonged to the state, and where the officers and directors were appointed by the state legislature. The Court narrowly defined a bill of credit as a note issued by the state, on the faith of the state, and designed to circulate as money. Since the notes in question were redeemable by the bank and not by the state itself, they were not bills of credit for constitutional purposes. By validating the constitutionality of state bank notes, the Supreme Court completed the financial revolution triggered by President Andrew Jackson's refusal to recharter the Second Bank of the United States and opened the door to greater state control of banking and currency in the antebellum period. The opinion given by the majority, which Taney was a part of, fit neatly into the Jacksonian economic plan by holding that the notes of the Bank of Kentucky were not bills of credit prohibited by the Constitution, even though the state owned the banks and the notes circulated by state law as legal. Thus, the bank notes were constitutional.

In Prigg v. Pennsylvania (1842), the Taney Court agreed to hear a case regarding slavery, slaves, slave owners, and states' rights. It held that the Constitutional prohibition against state laws that would emancipate any "person held to service or labor in [another] state" barred Pennsylvania from punishing a Maryland man who had seized a former slave and her child, and had taken them back to Maryland without seeking an order from the Pennsylvania courts permitting the abduction. In his opinion for the Court, Justice Joseph Story held not only that states were barred from interfering with enforcement of federal fugitive slave laws, but that they also were barred from assisting in enforcing those laws. In a concurring opinion, Taney argued that the constitutional guarantee of slaveholders' rights to ownership and the prohibition in Article IV against preventing slaves' return to their masters in Southern states imposed a positive duty on states to enforce federal fugitive slave laws.

Taney's 1849 majority opinion in Luther v. Borden provided an important rationale for limiting federal judicial power. The Court considered its own authority to issue rulings on matters deemed to be political in nature. Martin Luther, a Dorrite shoemaker, brought suit against Luther Borden, a state militiaman because Luther's house had been ransacked. Luther based his case on the claim that the Dorr government was the legitimate government of Rhode Island, and that Borden's violation of his home constituted a private act lacking legal authority. The circuit court, rejecting this contention, held that no trespass had been committed, and the Supreme Court, in 1849, affirmed. The decision provides the distinction between political questions and justiciable ones. Taney asserted that, "the powers given to the courts by the Constitution are judicial powers and extend to those subject, only, which are judicial in character, and not to those which are political."[10] The majority opinion interpreted the Guarantee Clause of the Constitution, Article IV, Section 4. Taney held that under this article Congress is able to decide what government is established in each state. This decision was important, because it is an example of judicial self-restraint. Many Democrats had hoped that the justices would legitimize the actions of the Rhode Island reformers. However, the justices' refusal to do so demonstrated the Court's independence and neutrality in a politically charged atmosphere. The Court showed that they could rise above politics and make the decision that it needed to make.

In 1852, the Genesee Chief v. Fitzhugh, dealt with the issue of admiralty jurisdiction. This case regarded a collision that occurred on Lake Ontario in 1847. The propeller of the boat, Genesee Chief, struck and sank the schooner, Cuba. Suing under the 1845 act that extended admiralty jurisdiction to the Great Lakes, the owners of the Cuba alleged that the negligence of the Genesee Chief caused the accident. Counsel for the Genesee Chief blamed the Cuba and contended that the incident occurred within New York's waters, outside the reach of federal jurisdiction. The key constitutional question was whether the case properly belonged in the federal courts. The case also derived its importance not from the facts of the collision, but about whether admiralty jurisdiction extended to the great freshwater lakes. In England, only tidal rivers had been navigable; hence, in English Law, the Admiralty Courts, which had been given jurisdiction over navigable waters, found their jurisdiction limited to places which felt the effect of the tides of the sea. In the United States, the vast expanse of the Great Lakes and stretches of the continental rivers, extending for hundreds of miles, were not tidal; yet upon these waters large vessels could move, with burdens of passengers and cargo. Taney ruled that the admiralty jurisdiction of the US Courts extends to waters, which are actually navigable, without regard to the flow of the ocean tides. Taney's majority opinion established a broad new definition of federal admiralty jurisdiction. According to Taney, the 1845 act fell within Congress's power to control the jurisdiction of the federal courts. "If this law, therefore, is constitutional, it must be supported on the ground that the lakes and navigable waters connecting them are within the scope of admiralty and maritime jurisdiction, as known and understood in the United States when the Constitution was adopted."[11] Taney's opinion marked a significant expansion of federal judicial power and an important step in establishing uniform federal admiralty principles.

Taney was instrumental in the case of John Merryman, a citizen of the state of Maryland who, in the early years of the American Civil War, was accused of burning bridges and destroying telegraph poles. He was seized in his home at 2:00 am by military authorities and taken to Fort McHenry. His was the first arrest under President Abraham Lincoln's suspension of the Writ of Habeas Corpus.

Dred Scott decision

In 1857 the Court heard Dred Scott v. Sandford; its decision is considered to have indirectly been a cause of the Civil War.[12] Despite the willingness of five members of the Court to dismiss the lawsuit by Dred Scott, on grounds situated in Missouri law governing who could sue and be sued, Taney wrote what came to be regarded as the opinion of the Court. His decision presented his version of the origins of the United States and the Constitution as the basis for his holding that Congress had no authority to restrict the spread of slavery into federal territories, and that such previous attempts to restrict slavery's spread as the 1820 Missouri Compromise were unconstitutional.[13]

Of the nine associate justices at the time, James Moore Wayne, John Catron, Peter Vivian Daniel, Samuel Nelson, Levi Woodbury, Robert Cooper Grier and John Archibald Campbell agreed with Taney, while John McLean and Benjamin Robbins Curtis dissented; the latter was so upset by the decision that he resigned from the court.[14]

The Dred Scott v. Sandford decision was widely condemned at the time by opponents of slavery as an illegitimate use of judicial power. Abraham Lincoln and the Republican Party accused the Taney Court of carrying out the orders of the "slave power" and of conspiring with President James Buchanan to undo the Missouri Compromise. Current scholarship supports that second charge, as it appears that Buchanan put significant political pressure behind the scenes on Justice Robert Grier to obtain at least one vote from a justice from outside the South to support the Court's sweeping decision.[15]

Taney's intemperate language only added to the fury of those who opposed the decision. As he explained his ruling, he noted that African Americans, free or slave, had not been considered part of the original community of people covered by the Constitution, but people of "an inferior order". Because they were originally excluded, he contended that neither the Court nor Congress could now extend rights of citizens to them.[13] The text of Taney's statement reads:

| “ | It is difficult at this day to realize the state of public opinion in regard to that unfortunate race which prevailed in the civilized and enlightened portions of the world at the time of the Declaration of Independence, and when the Constitution of the United States was framed and adopted; but the public history of every European nation displays it in a manner too plain to be mistaken. They had for more than a century before been regarded as beings of an inferior order, and altogether unfit to associate with the white race, either in social or political relations, and so far unfit that they had no rights which the white man was bound to respect.[13] | ” |

Some authors comment that "it seems unfair to quote the remark out of context which includes the phrase 'that unfortunate race,' etc."[16] Others maintain that Taney's statement here is willfully blind to the 1772 decision of Lord Mansfield in Somerset v Stewart, although three members of the Taney court produce opinions that argue at length about this decision.[12] Dissenting Justice Benjamin Robbins Curtis criticized Taney's version of the origins of the U.S. Constitution, pointing out: "In some of the States [...] colored persons were among those qualified by law to act on this subject. These colored persons were not only included in the body of 'the people of the United States,' by whom the Constitution was ordained and established, but in at least five of the States they had the power to act, and doubtless did act, by their suffrages, upon the question of its adoption. It would be strange, if we were to find in that instrument anything which deprived of their citizenship any part of the people of the United States who were among those by whom it was established."[17]

Taney's own attitudes toward slavery were more complex. He emancipated his own slaves[2] and gave pensions to those who were too old to work. In 1819, he defended a Methodist minister who had been indicted for inciting slave insurrections by denouncing slavery in a camp meeting. In his opening argument in that case, Taney condemned slavery as "a blot on our national character."[18]

Taney's attitudes toward slavery appeared to harden in support of the institution. By the time he wrote his Dred Scott opinion in 1857, he labeled the opposition to slavery as "northern aggression", a popular phrase among pro-slavery Southerners. He hoped that a Supreme Court decision declaring federal restrictions on slavery in the territories unconstitutional would put the issue beyond the realm of political debate. His decision instead galvanized Northern opposition to slavery while splitting the Democratic Party on sectional lines.

Many abolitionists — and some supporters of slavery — believed that Taney was prepared to rule that the states had no power to bar slaveholders from bringing their property into free states, and that laws of free states providing for the emancipation of slaves brought into their territory were unconstitutional. A case, Lemmon v. New York, that presented the issue was slowly making its way to the Supreme Court in the years after the Dred Scott decision, and the New York Court of Appeal had ruled in 1860. The case was appealed to the Supreme Court but never heard.

Lincoln presidency

Taney personally administered the oath of office to Lincoln, his most prominent critic, on March 4, 1861. He remained on the Court and did not go South to the Confederate States of America. His legal actions, however, sometimes frustrated Lincoln. After Lincoln suspended the writ of habeas corpus in parts of Maryland, Taney ruled as Circuit Judge in Ex parte Merryman (1861) that only Congress had the power to take this action. Lincoln ignored the court's order and continued to have arrests made without the privilege of the writ. Merryman was released to civil authorities and a federal grand jury in Baltimore charged him with treason on July 10, 1861.[19] Taney, whose health had never been good, spent his final years in worsening health, near poverty, and despised by both North and South. Since the Merryman ruling, he was all but ignored by Lincoln and his cabinet. His yearly salary remained at approximately $10,000 and the failing health of his daughter Ellen, who lived with him, prevented him from moving to cheaper quarters. The miserable financial situation was maddening to him. A few months later Taney wrote "about peaceful, bygone days ... walks in the fresh country air. But my walking days are over." [20]

On October 13, 1864, the clerk of the Supreme Court announced that "the great and good Chief Justice is no more." He had died at the age of eighty-seven the previous evening, having served for more than twenty-eight years as the fifth Chief Justice of the Supreme Court.

President Lincoln made no public statement. Of his cabinet, Lincoln and three members — Secretary of State William H. Seward, Attorney General Edward Bates, and Postmaster General William Dennison — attended Taney's memorial service in Washington. Only Bates joined the cortège to Frederick, Maryland for Taney's funeral and burial at St. John the Evangelist Cemetery.[21] Taney, whose wife had pre-deceased him by nine years, was survived by two daughters: the sickly Ellen, and a second, widowed daughter with a small child; he left a small life insurance policy and a bundle of worthless Virginia bonds.

Legacy

Taney's home, Taney Place, in Adelina, Calvert County, Maryland, was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1972.

Another property owned by Taney, although he never lived there, is in Frederick, Maryland. The Roger Brooke Taney House "including the house, detached kitchen, root cellar, smokehouse and slaves quarters, interprets the life of Taney and his wife Anne Key (sister of Francis Scott Key), as well as various aspects of life in early nineteenth century Frederick County."[22] A slave on that property, Margaret A. Hagen, believed herself to be the daughter of Judge Taney by a slave, Jane. Margaret was the mother-in-law of educator James Monroe Gregory and through him, she and Judge Taney are ancestors of dramatist Thomas Montgomery Gregory and astronaut Frederick Drew Gregory.[23]

Taney remained a controversial figure and he was attacked by abolitionists in the Senate even after his death. In early 1865, the House of Representatives passed a bill to appropriate funds for a bust of Chief Justice Taney to be displayed in the Supreme Court alongside those of his four predecessors.[24] In response, Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts said:

I speak what cannot be denied when I declare that the opinion of the Chief Justice in the case of Dred Scott was more thoroughly abominable than anything of the kind in the history of courts. Judicial baseness reached its lowest point on that occasion. You have not forgotten that terrible decision where a most unrighteous judgment was sustained by a falsification of history. Of course, the Constitution of the United States and every principle of Liberty was falsified, but historical truth was falsified also.[25][26]

After the 1873 death of Taney's successor, Chief Justice Salmon Chase, Congress approved funds for busts of Taney and Chase to be displayed in the Capitol alongside the other chief justices.

George Ticknor Curtis, one of the lawyers who argued before Taney on behalf of Dred Scott, held Taney in high esteem despite his decision in Dred Scott. In a volume of memoirs written for his brother Benjamin Robbins Curtis, who sat on the Supreme Court with Taney and dissented in Dred Scott, George Ticknor Curtis gave the following description of Taney:

He was indeed a great magistrate, and a man of singular purity of life and character. That there should have been one mistake in a judicial career so long, so exalted, and so useful is only proof of the imperfection of our nature. The reputation of Chief Justice Taney can afford to have anything known that he ever did and still leave a great fund of honor and praise to illustrate his name. If he had never done anything else that was high, heroic, and important, his noble vindication of the writ of habeas corpus, and of the dignity and authority of his office, against a rash minister of state, who, in the pride of a fancied executive power, came near to the commission of a great crime, will command the admiration and gratitude of every lover of constitutional liberty, so long as our institutions shall endure.[27]

Modern legal scholars have tended to concur with Curtis that despite the Dred Scott decision, Taney was both an outstanding jurist and a competent judicial administrator. His mixed legacy was noted by Justice Antonin Scalia in his dissenting opinion in Planned Parenthood v. Casey:

There comes vividly to mind a portrait by Emanuel Leutze that hangs in the Harvard Law School: Roger Brooke Taney, painted in 1859, the 82nd year of his life, the 24th of his Chief Justiceship, the second after his opinion in Dred Scott. He is all in black, sitting in a shadowed red armchair, left hand resting upon a pad of paper in his lap, right hand hanging limply, almost lifelessly, beside the inner arm of the chair. He sits facing the viewer, and staring straight out. There seems to be on his face, and in his deep set eyes, an expression of profound sadness and disillusionment. Perhaps he always looked that way, even when dwelling upon the happiest of thoughts. But those of us who know how the lustre of his great Chief Justiceship came to be eclipsed by Dred Scott cannot help believing that he had that case—its already apparent consequences for the Court, and its soon to be played out consequences for the Nation—burning on his mind.

Chief Justice Taney was the first of the 13 Catholic justices – out of 112 total – who have served on the Supreme Court.[28][29]

A statue of Taney stands on the grounds of the Maryland State House.[30]

Things named for Taney

- Taney County, Missouri, though it is usually pronounced /ˈteɪni/, not /ˈtɔːni/.

- A street in Baltimore.[31]

- A street in Philadelphia.[32]

- The Treasury-class US Coast Guard Cutter Taney. The ship is now part of the Baltimore Maritime Museum.

- The Liberty ship Roger B. Taney, commissioned on February 9, 1942. The ship undertook a 22-day, 2,600-mile journey in which it survived a hurricane and landed in the Bahamas. The ship was torpedoed in the South Atlantic on July 2, 1943. Three crew members died.[33]

- Roger B. Taney Middle School in Temple Hills, Maryland. After the population of the county changed to majority black, the school was renamed for Justice Thurgood Marshall.[34]

Taneytown, Maryland, in Carroll County, was established in 1754, and not named for Taney.

See also

Notes

- ↑ Described by his and President Andrew Jackson's critics as "[a] supple, cringing tool of Jacksonian power,"[1]

References

- ↑ Newmyer, R. Kent, The Supreme Court under Marshall and Taney, University of Connecticut (1968), p. 93

- 1 2 McNeal, J., "Roger Brooke Taney", The Catholic Encyclopedia, New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1912. Retrieved May 28, 2009 from New Advent.

- ↑ "Dred Scott case". PBS/WGBH. Retrieved January 23, 2016.

- ↑ "CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA: Roger Brooke Taney". Retrieved January 23, 2016.

- ↑ Tyler, Samuel, Memoir of Roger Brooke Taney, LLD, p. 35, 1872

- ↑ "Roger Brooke Taney, class of 1795". Dickinson College. Retrieved October 22, 2007.

- ↑ "Roger Brooke Taney". NNDB: Tracking the Whole Entire World. Soylent Communications. Retrieved July 7, 2012.

- ↑ "Nominations: Chapter 5: Andrew Jackson". United States Senate. Retrieved April 26, 2010. In the final week of the congressional session, Jackson nominated Attorney General Roger B. Taney as secretary of the treasury. Taney had been the architect of Jackson's plan to dismantle the bank. A day later, a pro-bank majority in the Senate, including both senators from Taney's Maryland, voted 18 to 28 to deny Taney the post, making him the first cabinet nominee to be openly rejected.

- 1 2 Charles River Bridge v. Warren Bridge, 36 US 420 (1837).

- ↑ Luther v. Borden, 48 US 1 (1849).

- ↑ The Propeller Genesee Chief v. Fitzhugh, 53 US 443 (1851).

- 1 2 e.g. Blumrosen & Blumrosen, "Slave Nation", p.249

- 1 2 3 Scott v. Sanford, 60 U.S. (19 How.) 393 (1857)

- ↑ Ariens, Michael. "Roger B. Taney". Michaelariens.com. Archived from the original on May 16, 2008. Retrieved May 26, 2012.

- ↑ Schwartz, Bernard (1995). A History of the Supreme Court. Oxford University Press. p. 114. Retrieved August 20, 2012.

- ↑ Burnham, Tom: "Dictionary of Misinformation" (1975) p.257

- ↑ Fox, John. "The First Hundred Years: Biographies of the Robes, Benjamin Robinson Curtis". Public Broadcasting Service. Retrieved May 13, 2012..

- ↑ Huebner, Timothy S. (2010). "Roger B. Taney and the Slavery Issue: Looking beyond--and before--Dred Scott". Journal Of American History. 97 (1): 17–38 – via Education Source, EBSCOhost.

- ↑ White, Jonathan W. (2011). Abraham Lincoln and Treason in the Civil War: The Trials of John Merryman. Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press. p. 46. ISBN 978-0-8071-4346-9.

- ↑ James F. Simon Lincoln and Chief Justice Taney: Slavery, Secession, and the President's War Powers (Simon and Schuster, 2006), p. 245–246.

- ↑ Christensen, George A. (1983) Here Lies the Supreme Court: Gravesites of the Justices, Yearbook at the Wayback Machine (archived September 3, 2005) Supreme Court Historical Society at Internet Archive.

- ↑ "Roger Brooke Taney House : General Information". Historical Society of Frederick County. Retrieved January 23, 2016.

- ↑ Cross, June. "The Family That Adopted June, The Gregory Family", Frontline, PBS, accessed November 11, 2016 at http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/secret/readings/gregory.html

- ↑ Roger B. Taney by Augustus Saint-Gaudens (1848–1907) Marble, 1876 ca. United States Senate Arts and History.

- ↑ Konig, David Thomas; Finkelman, Paul; Bracey, Christopher Alan (2014). The Dred Scott Case: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives on Race and Law. Ohio University Press. p. 228.

- ↑ Simon, James, F., Lincoln and Chief Justice Taney,(Simon and Schuster, 2006) p. 268

- ↑ Curtis, Benjamin R., ed. (November 1, 2002) [1879]. A Memoir of Benjamin Robbins Curtis, LL.D. with some of his Professional and Miscellaneous Writings, Vol. I. The Lawbook Exchange, Ltd. pp. 239–240. ISBN 1-58477-235-2. Retrieved January 23, 2016.

- ↑ Religious affiliation of Supreme Court justices Justice Sherman Minton converted to Catholicism after his retirement. James F. Byrnes was raised as Catholic, but converted to Episcopalianism before his confirmation as a Supreme Court Justice.

- ↑ "Boston Globe article about Sotomayor's religion". Boston.com. Retrieved May 26, 2012.

- ↑ "Roger B. Taney", Maryland State Archives

- ↑ Taney Rd (January 1, 1970). "taney road baltimore - Google Maps". Maps.google.com. Retrieved May 26, 2012.

- ↑ "Liberty Ship SS Roger B. Taney". Ahoy.tk-jk.net. Retrieved May 26, 2012.

- ↑ "School May Change Name To Thurgood Marshall". Upper Marlboro, Maryland: Orlando Sentinel. March 2, 1993. Retrieved November 7, 2011.

Further reading

- Abraham, Henry J. (1992). Justices and Presidents: A Political History of Appointments to the Supreme Court (3rd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-506557-3.

- Cushman, Clare (2001). The Supreme Court Justices: Illustrated Biographies, 1789–1995 (2nd ed.). (Supreme Court Historical Society, Congressional Quarterly Books). ISBN 1-56802-126-7.

- Flanders, Henry (1874). The Lives and Times of the Chief Justices of the United States Supreme Court. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott & Co. (at Google Books)

- Frank, John P. (1995). Friedman, Leon; Israel, Fred L., eds. The Justices of the United States Supreme Court: Their Lives and Major Opinions. Chelsea House Publishers. ISBN 0-7910-1377-4.

- Hall, Kermit L., ed. (1992). The Oxford Companion to the Supreme Court of the United States. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-505835-6.

- Huebner, Timothy S. (2003). The Taney Court, Justice Rulings and Legacy. Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-Clio. ISBN 1-57607-368-8.

- ——— (2010). "Roger Taney and the Slavery Issue: Looking Beyond—and Before—Dred Scott". Journal of American History. 97: 39–62.

- Lewis, Walker (1965). Without Fear or Favor: A Biography of Chief Justice Roger Brooke Taney. Boston: Houghton Mifflin., focus on personal life

- Swisher, Carl B. Roger B. Taney (1935), full-length scholarly biography review of Swisher

- Simon, James F. (2006). Lincoln and Chief Justice Taney: Slavery, Secession, and the President's War Powers (Paperback ed.). New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-7432-9846-2.

- Urofsky, Melvin I. (1994). The Supreme Court Justices: A Biographical Dictionary. New York: Garland Publishing. p. 590. ISBN 0-8153-1176-1.

- VanBurkleo, Sandra F. and Bonnie Speck. "Taney, Roger Brooke"; American National Biography Online February 2000. Accessed October 29, 2014

- White, G. Edward. in The American Judicial Tradition (2nd ed. 1988), chapter on Taney

External links

- Roger B. Taney at the Biographical Directory of Federal Judges, a public domain publication of the Federal Judicial Center.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Roger B. Taney. |

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Roger B. Taney |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Roger B. Taney |

- Biography from FindLaw.

- Fox, John, Capitalism and Conflict, Biographies of the Robes, Roger Taney. Public Broadcasting Service.

- Roger Brooke Taney memorial at Find a Grave.

- Oyez.org Supreme Court media on Roger B. Taney.

- Roger Brooke Taney Home/Museum in Frederick, MD.

| Legal offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Thomas Kell |

Attorney General of Maryland 1827–1831 |

Succeeded by Josiah Bayly |

| Preceded by John Berrien |

United States Attorney General 1831–1833 |

Succeeded by Benjamin Butler |

| Preceded by John Marshall |

Chief Justice of the Supreme Court 1836–1864 |

Succeeded by Salmon Chase |

| Political offices | ||

| Preceded by John Eaton |

United States Secretary of War Acting 1831 |

Succeeded by Lewis Cass |

| Preceded by William Duane |

United States Secretary of the Treasury 1833–1834 |

Succeeded by Levi Woodbury |

| | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||