Rose Hill Packet

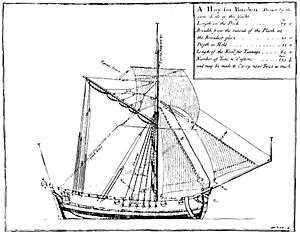

18th-century diagram of a hoy, with the names of essential parts and a legend giving dimensions[1] | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | Rose Hill Packet |

| Builder: | Robinson Reid, King's Slipway, Sydney |

| Laid down: | 30 December 1788 |

| Launched: | September 1789 |

| Commissioned: | 5 October 1789 |

| Decommissioned: | c.1800 |

| In service: | 1789 - 1800 |

| Fate: | brocken up |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type: | Packet or Hoy |

| Tons burthen: | 12 (bm) |

| Length: | 38-42" |

| Beam: | 16-18" |

| Draught: | less than two fathoms |

| Propulsion: | Sail, oars or poles |

| Sail plan: | cutter |

| Complement: | 8-10 |

Rose Hill Packet, was a marine craft built in Australia, named after the second place of European settlement in Australia, "Rose Hill", the furthest navigable point inland on the Parramatta River. The boat design was later called a packet (or mail) boat, because its use was that of running the first Parramatta River trade ferry, passenger, cargo, and mail service between the Sydney Cove and the Rose Hill (Parramatta) First Fleet settlements after she was launched in Sydney Cove in September and commissioned on 5 October 1789. She was the first purpose-built sailing vessel constructed in Australia.

Authorising construction

Governor Arthur Phillip had appointed a Midshipman, Henry Brewer, as temporary superintendent of building works in the colony seven years before. In 1796, Governor John Hunter would establish a government shipyard in Sydney Town. The craft was laid down on 30 December 1788[2] on King's Slipway, later the James Underwood yards on the east side of Sydney Cove, somewhere near the site of the present Customs House, by convicts under supervision of Robinson Reid, a carpenter from HMS Supply.

Construction resource problems

Fourteen ship's carpenters are known to have been sailing with the First Fleet ships, so the selection of Reed as the builder was unlikely to have been accidental.[3] Unfortunately the quality of local timber left few options for the construction, and "From the quantity of wood used, she appeared to be a 'mere bed of timber." What made construction difficult was the lack of specialised shipbuilding tools, and many of the carpentry tools intended for use in the cutting and shaping of the European timbers turned out to be unsuitable for the task mainly due to the density of the local hardwood timber.[4] Although there were sixteen ship's carpenters in the colony, of the convicts used in the building of the packet only twelve were trained as carpenters. All these factors forced excessive use of timber.

Australian timbers in early shipbuilding attempts

The difficulties in constructing Rose Hill Packet lay with the type of timber readily available in the Sydney area, the Sydney red gum. Some trees were 23 metres (75 ft) or more high with no lateral branches until 15 metres (49 ft). Their girth could measure in excess of 8 metres (26 ft) in diameter, but the trunks were hollow and rotten in eleven out of a dozen felled trees. Cox and Freeland describe the species as, "almost without exception, they rot out at the heart before they are any useful size leaving a mere shell of living sound wood."[5] It was found that no matter in what way it was sawn or how well it was dried, that when placed in water "it sinks to the bottom like a stone."[6] Members of the First Fleet soon realised that, "despite their amazing size the trees were scarcely worth cutting down."[7] Several years later, George Thompson summed up Australian timber as "of little use - not fit for building either houses or boats."[8] It wasn't until later that Australian settlers found that the most useful timbers for boat and ship building were the Eucalypts species: iron bark, stringy bark, box and the blackbutt, the bluegum, and turpentine. Consequently, the axes, saws and chisels used by carpenters broke or became blunt with the unfamiliar timber which only much later was discovered to have a density three times that of the European Oak.[9] To add to their woes, the red gum began to split and warp almost as soon as it was cut, making the usual seasoning impossible, and forcing the use of green timber. However, the same timber after being seasoned for 15 years was reportedly very strong and suitable by the time the colony's first three-masted ship King George was being built.[4]

Craft design

Reid called the craft a 20-ton (about 15.9m3) launch, a term appropriate for the Royal Navy service, which would produce a 38–42-foot (12–13 m) craft, larger than any fleet ships could have carried on board to the new colony. No plans or illustrations survivve. Several contemporary accounts reported her to be 10 or 12 ton, or alternatively the size of a small hoy-decked boat, which in England were commonly sloop-rigged, designed for inshore work. She carried a single mast, and was also provided with oars, reportedly requiring occasional use of poles due to her "heaviness", however this refers to a vessel's handling during sailing, not physical weight. The naming confusion perhaps stemms from the variety of coastal craft used in Britain at the time: the English Cutter of the late 18th century, the Margate hoy used for Channel crossing, the Leith sloop, and the English Channel packet-boat. However, the description closely matches the Southampton fishing hoys, with "heavy", i.e. nearly vertical, stem and stern posts, larger than expected beams and rounded mid-ship sections. The clinker-built[10] Southampton fishing hoys carried the smack or cutter rigs rather than the sloop rigs of the south-eastern English coast (Dover & Thames) hoys.[11]

David Steel's The Elements and Practice of Naval Architecture. Illustrated with a series of Thirty-Eight Large Draughts and Numerous Smaller Engravings, 1805 illustrates a 13-ton hoy of this type on Plate XXVIII. The reason for the design and rig differences are suggested by the need to navigate the Solent within the proximity of the Isle of Wight with its Eastern Solent, Portsmouth road, Bramble Bank, Bembridge Ledges, and Needles Channel hazards. It is then understandable where the design came from since the First Fleet set sail from Portsmouth, 19 miles (31 km) south east of Southampton. When launched, was named by the convicts, the Rose Hill Packet, but afterwards, was appropriately known by the name of 'The Lump'.[12]

Craft's performance

Despite the colloquial name given to the Packet, it did not necessarily refer to the 'ugliness' of construction, or the lack of construction skills, but the actual design shape produced by the stem and stern rakes, because in use she was "...going up with the tide of flood, at the top of high water, she passed very well over the flats at the upper part of the (Parramatta river) harbour."[13] Reports suggest she could carry up to thirty passengers on deck.

Because of the amount of timber used, the craft's performance was considered sluggish, and she was an awkward looking row-and-sail boat. As much as the service was useful to the settlers, the craft lacked durability due to use of green timber, and was difficult in operating, sometimes even requiring the passengers to assist in rowing. Other lighter sailing craft and rowing boats were soon brought into service as ferries across the Harbour to Manly Cove and up and down the river.

The packet service was discontinued by 1800.

References

- ↑ Sutherland 1717, facing p. 17.

- ↑ Samuel Bennett, The history of Australian discovery and colonisation, p.140

- ↑ Fellowship of the First Fleeters

- 1 2 Tuckey's observations on the various kinds of timber found in New South Wales in 1804

- ↑ Cox, P. & Freeland, J. Rude Timber Buildings in Australia. Thames and Hudson. London. 1969. pp.9-27

- ↑ John White, Journal of a Voyage to New South Wales, 1787-1788

- ↑ ibid.

- ↑ H.R.N.S.W. (Historical Records of New South Wales). [1893] . Lansdown Slattery & Company. Sydney. (1978) Volume 1, p.128 & volume 2, p.799

- ↑ Archer, J. Building a Nation; A History of the Australian House. Collins. Sydney. 1987. pp. 6-16, 25

- ↑ Mike Smylie, Traditional Fishing Boats of Britain & Ireland, Amberley Publishing Limited, 2012

- ↑ E. W. White, British Fishing-Boats and Coastal Craft, H.M.S.O., London, 1950

- ↑ T. Cadell and W. Davies, An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales: From Its First Settlement in January 1788, to August 1801, 1804, pp.70-71

- ↑ ibid.

Recommended reading

- Walker, M. 1978. Pioneer Crafts of Early Australia. The Macmillan Company of Australia Pty Ltd. Melbourne.

External links

- Rose Hill Packet in the Dictionary of Sydney, 2008. [CC-By-SA]