SMS Markgraf

Recognition drawing of a König-class battleship | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Builder: | AG Weser, Bremen |

| Laid down: | November 1911 |

| Launched: | 4 June 1913 |

| Commissioned: | 1 October 1914 |

| Fate: | Scuttled 21 June 1919 in Gutter Sound, Scapa Flow |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type: | König-class battleship |

| Displacement: |

|

| Length: | 175.4 m (575 ft 6 in) |

| Beam: | 29.5 m (96 ft 9 in) |

| Draft: | 9.19 m (30 ft 2 in) |

| Installed power: | 40,830 shp (30,450 kW) |

| Propulsion: |

|

| Speed: | 21 knots (39 km/h; 24 mph) |

| Range: | 8,000 nmi (15,000 km; 9,200 mi) at 12 knots (22 km/h; 14 mph) |

| Crew: |

|

| Armament: |

|

| Armor: |

|

SMS Markgraf[lower-alpha 1] was the third battleship of the four-ship König class. She served in the Imperial German Navy during World War I. The battleship was laid down in November 1911 and launched on 4 June 1913. She was formally commissioned into the Imperial Navy on 1 October 1914, just over two months after the outbreak of war in Europe. Markgraf was armed with ten 30.5-centimeter (12.0 in) guns in five twin turrets and could steam at a top speed of 21 knots (39 km/h; 24 mph). Markgraf was named in honor of the royal family of Baden. The name Markgraf is a rank of German nobility and is equivalent to the English Margrave, or Marquess.

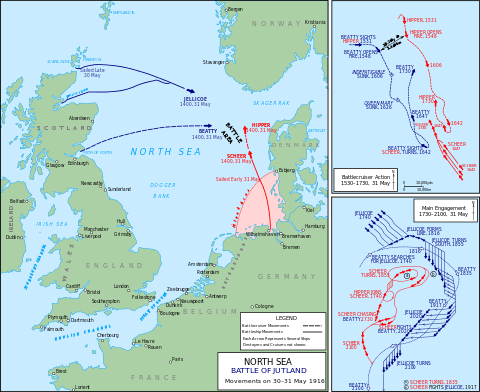

Along with her three sister ships, König, Grosser Kurfürst, and Kronprinz, Markgraf took part in most of the fleet actions during the war, including the Battle of Jutland on 31 May and 1 June 1916. At Jutland, Markgraf was the third ship in the German line and heavily engaged by the opposing British Grand Fleet; she sustained five large-caliber hits and her crew suffered 23 casualties. Markgraf also participated in Operation Albion, the conquest of the Gulf of Riga, in late 1917. The ship was damaged by a mine while en route to Germany following the successful conclusion of the operation.

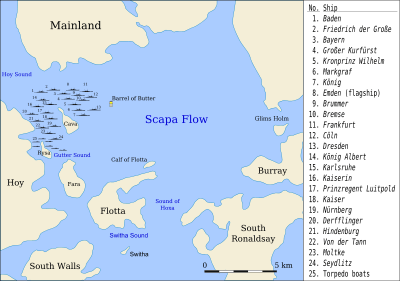

After Germany's defeat in the war and the signing of the Armistice in November 1918, Markgraf and most of the capital ships of the High Seas Fleet were interned by the Royal Navy in Scapa Flow. The ships were disarmed and reduced to skeleton crews while the Allied powers negotiated the final version of the Treaty of Versailles. On 21 June 1919, days before the treaty was signed, the commander of the interned fleet, Rear Admiral Ludwig von Reuter, ordered the fleet to be scuttled to ensure that the British would not be able to seize the ships. Unlike most of the scuttled ships, Markgraf was never raised for scrapping; the wreck is still sitting on the bottom of the bay.

Construction and design

Markgraf was ordered under the provisional name Ersatz Weissenburg and built at the AG Weser shipyard in Bremen under construction number 186.[1][lower-alpha 2] Her keel was laid in November 1911 and she was launched on 4 June 1913.[2] At her launching ceremony, the ship was christened by Frederick II, Grand Duke of Baden, the head of the royal family of Baden, in honor of which the ship had been named.[3] Fitting-out work was completed by 1 October 1914, the day she was commissioned into the High Seas Fleet.[4] She had cost the Imperial German Government 45 million Goldmarks.[1]

Markgraf displaced 25,796 t (25,389 long tons) as built and 28,600 t (28,100 long tons) fully loaded, with a length of 175.4 m (575 ft 6 in), a beam of 19.5 m (64 ft 0 in) and a draft of 9.19 m (30 ft 2 in). She was powered by three Bergmann steam turbines, three oil-fired and twelve coal-fired boilers, which developed a total of 40,830 shp (30,450 kW) and yielded a maximum speed of 21 knots (39 km/h; 24 mph). The ship had a range of 8,000 nautical miles (15,000 km; 9,200 mi) at a cruising speed of 12 knots (22 km/h; 14 mph).[1] The ship had a crew of 41 officers and 1,095 enlisted sailors.[4]

She was armed with ten 30.5 cm (12.0 in) SK L/50 guns arranged in five twin gun turrets: two superfiring turrets each fore and aft and one turret amidships between the two funnels. Her secondary armament consisted of fourteen 15 cm (5.9 in) SK L/45 quick-firing guns, six 8.8 cm (3.5 in) SK L/45 quick-firing guns and five 50 cm (20 in) underwater torpedo tubes, one in the bow and two on each beam.[4] Markgraf's 8.8 cm guns were removed and replaced with four 8.8 cm anti-aircraft guns.[5] The ship's main armored belt was 350 millimeters (14 in) thick. The deck was 30 mm (1.2 in) thick; the main battery turrets and forward conning tower were armored with 300 mm (12 in) thick steel plates.[4]

Service history

Following her commissioning on 1 October 1914, Markgraf conducted sea trials, which lasted until 12 December. By 10 January 1915, the ship had joined III Battle Squadron of the High Seas Fleet with her three sister ships.[6] On 22 January 1915, III Squadron was detached from the fleet to conduct maneuver, gunnery, and torpedo training in the Baltic. The ships returned to the North Sea on 11 February, too late to assist the I Scouting Group at the Battle of Dogger Bank.[7]

In the aftermath of the loss of SMS Blücher at the Battle of Dogger Bank, Kaiser Wilhelm II removed Admiral Friedrich von Ingenohl from his post as fleet commander on 2 February. Admiral Hugo von Pohl replaced him as commander of the fleet; von Pohl carried out a series of sorties with the High Seas Fleet throughout 1915.[8] The first such operation—Markgraf's first with the fleet—was a fleet advance to Terschelling on 29–30 March; the German fleet failed to engage any British warships during the sortie. Another uneventful operation followed on 17–18 April, and another three days later on 21–22 April. Markgraf and the rest of the fleet remained in port until 29 May, when the fleet conducted another two-day advance into the North Sea. On 11–12 September, Markgraf and the rest of III Squadron supported a minelaying operation off Texel. Another uneventful fleet advance followed on 23–24 October.[6]

Vice Admiral Reinhard Scheer became commander in chief of the High Seas Fleet on 18 January 1916 when Admiral von Pohl became too ill from liver cancer to continue in that post.[9] Scheer proposed a more aggressive policy designed to force a confrontation with the British Grand Fleet; he received approval from the Kaiser in February.[10] The first of Scheer's operations was conducted the following month, on 5–7 March, with an uneventful sweep of the Hoofden.[11] Another sortie followed three weeks later on the 26th, with another on 21–22 April.[6] On 24 April, the battlecruisers of Rear Admiral Franz von Hipper's I Scouting Group conducted a raid on the English coast. Markgraf and the rest of the fleet sailed in distant support. The battlecruiser Seydlitz struck a mine while en route to the target, and had to withdraw.[12] The other battlecruisers bombarded the town of Lowestoft unopposed, but during the approach to Yarmouth, they encountered the British cruisers of the Harwich Force. A short artillery duel ensued before the Harwich Force withdrew. Reports of British submarines in the area prompted the retreat of the I Scouting Group. At this point, Scheer, who had been warned of the sortie of the Grand Fleet from its base in Scapa Flow, also withdrew to safer German waters.[13]

Battle of Jutland

Markgraf was present during the fleet operation that resulted in the Battle of Jutland which took place on 31 May and 1 June 1916. The German fleet again sought to draw out and isolate a portion of the Grand Fleet and destroy it before the main British fleet could retaliate. Markgraf was the third ship in the German line, behind her sisters König and Grosser Kurfürst and followed by Kronprinz. The four ships made up the V Division of the III Battle Squadron, and they were the vanguard of the fleet. The III Battle Squadron was the first of three battleship units; directly astern were the Kaiser-class battleships of the VI Division, III Battle Squadron. The III Squadron was followed by the Helgoland and Nassau classes of the II Battle Squadron; in the rear guard were the obsolescent Deutschland-class pre-dreadnoughts of the I Battle Squadron.[14]

Shortly before 16:00 the battlecruisers of I Scouting Group encountered the British 1st Battlecruiser Squadron under the command of Vice Admiral David Beatty. The opposing ships began an artillery duel that saw the destruction of Indefatigable, shortly after 17:00,[15] and Queen Mary, less than half an hour later.[16] By this time, the German battlecruisers were steaming south to draw the British ships toward the main body of the High Seas Fleet. At 17:30, König's crew spotted both the I Scouting Group and the 1st Battlecruiser Squadron approaching. The German battlecruisers were steaming to starboard, while the British ships steamed to port. At 17:45, Scheer ordered a two-point turn to port to bring his ships closer to the British battlecruisers, and a minute later, the order to open fire was given.[17][lower-alpha 3]

Markgraf opened fire on the battlecruiser Tiger at a range of 21,000 yards (19,000 m).[17] Markgraf and her two sisters fired their secondary guns on British destroyers attempting to make torpedo attacks against the German fleet.[18][lower-alpha 4] Markgraf continued to engage Tiger until 18:25, by which time the faster battlecruisers managed to move out of effective gunnery range.[19] During this period, the battleships Warspite and Valiant of the 5th Battle Squadron fired on the leading German battleships.[20] At 18:10, one of the British ships scored a 15-inch (38 cm) shell hit on Markgraf.[21] Shortly thereafter, the destroyer Moresby fired a single torpedo at Markgraf and missed from a range of about 8,000 yd (7,300 m).[22] Malaya fired a torpedo at Markgraf at 19:05, but the torpedo missed due to the long range.[23] Around the same time, Markgraf engaged a cruiser from the 2nd Light Cruiser Squadron before shifting her fire back to the 5th Battle Squadron for ten minutes.[24] During this period, two more 15-inch shells hit Markgraf, though the timing is unknown. The hit at 18:10 struck on a joint between two 8-inch-thick side armor plates; the shell burst on impact and holed the armor. The main deck was buckled and approximately 400 t (390 long tons; 440 short tons) of water entered the ship. The other two shells failed to explode and caused negligible damage.[25]

Shortly after 19:00, the German cruiser Wiesbaden had become disabled by a shell from the British battlecruiser Invincible; Rear Admiral Paul Behncke in König attempted to position his four ships to cover the stricken cruiser.[26] Simultaneously, the British III and IV Light Cruiser Squadrons began a torpedo attack on the German line; while advancing to torpedo range, they smothered Wiesbaden with fire from their main guns. The obsolescent armored cruisers of the 1st Cruiser Squadron also joined in the melee. Markgraf and her sisters fired heavily on the British cruisers, but even sustained fire from the battleships' main guns failed to drive them off.[27] Markgraf fired both her 30.5 cm and 15 cm guns at the armored cruiser Defence. Under a hail of fire from the German battleships, Defence exploded and sank;[28] credit is normally given to the battlecruiser Lützow, though Markgraf's gunners also claimed credit for the sinking.[29]

Markgraf then fired on the battlecruiser Princess Royal and scored two hits.[28] The first hit struck the 9-inch armor covering "X" barbette, was deflected downward, and exploded after penetrating the 1-inch deck armor. The crew for the left gun were killed, the turret was disabled, and the explosion caused serious damage to the upper deck. The second shell penetrated Princess Royal's 6-inch belt armor, ricocheted upward off the coal bunker, and exploded under the 1-inch deck armor. The two shells killed 11 and wounded 31.[30] At the same time, Markgraf's secondary guns fired on the cruiser Warrior, which was seriously damaged by 15 heavy shells and forced to withdraw. Warrior foundered on the trip back to port the following morning.[31]

Around 19:30, Admiral John Jellicoe's main force of battleships entered the battle;[32] Orion began firing at Markgraf at 19:32; she fired four salvos of 13.5-inch Armor-Piercing, Capped (APC) shells and scored a hit with the last salvo.[33] The shell exploded upon impacting the armor protecting the No. 6 15 cm gun casemate. The shell failed to penetrate but holed the armor and disabled the gun. The explosion seriously injured two and killed the rest of the gun crew. A heavy shell nearly struck the ship at the same time, and at 19:44, a bent propeller shaft forced Markgraf's crew to turn off the port engine; naval historian John Campbell speculated that this shell was the one that damaged the shaft.[34] Her speed dropped to 17 or 18 kn (31 or 33 km/h; 20 or 21 mph), though she remained in her position in the line.[35]

Shortly after 20:00, the German battleships engaged the 2nd Light Cruiser Squadron; Markgraf fired primarily 15 cm shells.[36] In this period, Markgraf was engaged by Agincourt's 12-inch guns, which scored a single hit at 20:14.[37] The shell failed to explode and shattered on impact on the 8-inch side armor, causing minimal damage. Two of the adjoining 14-inch plates directly below the 8-inch armor were slightly forced inward and some minor flooding occurred.[38] The heavy fire of the British fleet forced Scheer to order the fleet to turn away.[39] Due to her reduced speed, Markgraf turned early in an attempt to maintain her place in the battle line; this, however, forced Grosser Kurfürst to fall out of formation. Markgraf fell in behind Kronprinz while Grosser Kurfürst steamed ahead to return to her position behind König.[40] After successfully withdrawing from the British, Scheer ordered the fleet to assume night cruising formation, though communication errors between Scheer aboard Friedrich der Grosse and Westfalen, the lead ship, caused delays.[41] Several British light cruisers and destroyers stumbled into the German line around 21:20. In the ensuing short engagement Markgraf hit the cruiser Calliope five times with her secondary guns.[42] The fleet fell into formation by 23:30, with Grosser Kurfürst the 13th vessel in the line of 24 capital ships.[41]

Around 02:45, several British destroyers mounted a torpedo attack against the rear half of the German line. Markgraf initially held her fire as the identities of the destroyers were unknown. But gunners aboard Grosser Kurfürst correctly identified the vessels as hostile and opened fire while turning away to avoid torpedoes, which prompted Markgraf to follow suit.[43] Heavy fire from the German battleships forced the British destroyers to withdraw.[44] At 05:06, Markgraf and several other battleships fired at what they thought was a submarine.[45]

The High Seas Fleet managed to punch through the British light forces without drawing the attention of Jellicoe's battleships, and subsequently reached Horns Reef by 04:00 on 1 June.[46] Upon reaching Wilhelmshaven, Markgraf went into harbor while several other battleships took up defensive positions in the outer roadstead.[47] The ship was transferred to Hamburg where she was repaired in AG Vulcan's large floating dock. Repair work was completed by 20 July.[48] In the course of the battle, Markgraf had fired a total of 254 shells from her main battery and 214 rounds from her 15 cm guns.[49] She was hit by five large-caliber shells, which killed 11 men and wounded 13.[50]

Subsequent operations

Following repairs in July 1916, Markgraf went into the Baltic for trials. The ship was then temporarily assigned to the I Scouting Group for the fleet operation on 18–19 August. Due to the serious damage incurred by Seydlitz and Derfflinger at Jutland, the only battlecruisers available for the operation were Von der Tann and Moltke, which were joined by Markgraf, Grosser Kurfürst, and the new battleship Bayern.[6] The British were aware of the German plans, and sortied the Grand Fleet to meet them. By 14:35, Scheer had been warned of the Grand Fleet's approach and, unwilling to engage the whole of the Grand Fleet just 11 weeks after the decidedly close engagement at Jutland, turned his forces around and retreated to German ports.[51]

Markgraf was present for the uneventful advance in the direction of Sunderland on 18–20 October. Unit training with the III Squadron followed from 21 October to 2 November. Two days later, the ship formally rejoined III Squadron. On the 5th, a pair of U-boats grounded on the Danish coast. Light forces were sent to recover the vessels, and III Squadron, which was in the North Sea en route to Wilhelmshaven, was ordered to cover them.[6] During the operation, the British submarine J1 torpedoed both Grosser Kurfürst and Kronprinz and caused moderate damage.[52] For most of 1917, Markgraf was occupied with guard duties in the North Sea, interrupted only by a refit period in January and periodic unit training in the Baltic.[6]

Operation Albion

In early September 1917, following the German conquest of the Russian port of Riga, the German navy decided to eliminate the Russian naval forces that still held the Gulf of Riga. The Admiralstab (Navy High Command) planned an operation to seize the Baltic island of Ösel, and specifically the Russian gun batteries on the Sworbe Peninsula.[53] On 18 September, the order was issued for a joint operation with the army to capture Ösel and Moon Islands; the primary naval component was to comprise the flagship, Moltke, along with the III and IV Battle Squadrons of the High Seas Fleet. The II Squadron consisted of the four König-class ships, and was by this time augmented with the new battleship Bayern. The IV Squadron consisted of the five Kaiser-class battleships. Along with nine light cruisers, three torpedo boat flotillas, and dozens of mine warfare ships, the entire force numbered some 300 ships, supported by over 100 aircraft and six zeppelins. The invasion force amounted to approximately 24,600 officers and enlisted men.[54]

Opposing the Germans were the old Russian pre-dreadnoughts Slava and Tsesarevich, the armored cruisers Bayan, Admiral Makarov, and Diana, 26 destroyers, and several torpedo boats and gunboats. Three British C-class submarines where also stationed in the Gulf. The Irben Strait, the main southern entrance to the Gulf of Riga, was heavily mined and defended by a number of coastal artillery batteries. The garrison on Ösel numbered nearly 14,000 men, though by 1917 it had been reduced to 60 to 70 percent strength.[55]

The operation began on 12 October, when Moltke and the four König-class ships covered the landing of ground troops by suppressing the shore batteries covering Tagga Bay.[55] Markgraf fired on the battery located on Cape Ninnast. After the successful amphibious assault, III Squadron steamed to Putziger Wiek, although Markgraf remained behind for several days. On the 17th, Markgraf left Tagga Bay to rejoin her squadron in the Gulf of Riga, but early on the following morning she ran aground at the entrance to Kalkgrund. The ship was quickly freed, and she reached the III Squadron anchorage north of Larina Bank on the 19th. The next day, Markgraf steamed to Moon Sound, and on the 25th participated in the bombardment of Russian positions on the island of Kynö. The ship returned to Arensburg on 27 October, and two days later was detached from Operation Albion to return to the North Sea.[56]

Markgraf struck a pair of mines in quick succession while in the Irben Strait and took in 260 metric tons (260 long tons; 290 short tons) of water. The ship continued on to Kiel via Neufahrwasser in Danzig; she then went on to Wilhelmshaven, where the mine damage was repaired. The work was completed at the Imperial Dockyard from 6 to 23 November.[6] After repairs were completed, Markgraf returned to guard duty in the North Sea. She missed an attempted raid on a British convoy on 23–25 April 1918, as she was in dock in Kiel from 15 March to 5 May for the installation of a new foremast.[56]

Fate

Markgraf and her three sisters were to have taken part in a final fleet action at the end of October 1918, days before the Armistice was to take effect. The bulk of the High Seas Fleet was to have sortied from their base in Wilhelmshaven to engage the British Grand Fleet. Scheer—by now the Grand Admiral (Großadmiral) of the fleet—intended to inflict as much damage as possible on the British navy in order to obtain a better bargaining position for Germany, despite the expected casualties. However, many of the war-weary sailors felt the operation would disrupt the peace process and prolong the war.[57] On the morning of 29 October 1918, the order was given to sail from Wilhelmshaven the following day. Starting on the night of 29 October, sailors on Thüringen and then on several other battleships, including Markgraf, mutinied.[58] The unrest ultimately forced Hipper and Scheer to cancel the operation.[59] Informed of the situation, the Kaiser stated, "I no longer have a navy."[60]

Following the capitulation of Germany in November 1918, most of the High Seas Fleet ships, under the command of Rear Admiral Ludwig von Reuter, were interned in the British naval base in Scapa Flow.[59] Prior to the departure of the German fleet, Admiral Adolf von Trotha made clear to von Reuter that he could not allow the Allies to seize the ships, under any conditions.[61] The fleet rendezvoused with the British light cruiser Cardiff, which led the ships to the Allied fleet that was to escort the Germans to Scapa Flow. The massive flotilla consisted of some 370 British, American, and French warships.[62] Once the ships were interned, their guns were disabled through the removal of their breech blocks, and their crews were reduced to 200 officers and enlisted men.[63]

The fleet remained in captivity during the negotiations that ultimately produced the Treaty of Versailles. Von Reuter believed that the British intended to seize the German ships on 21 June 1919, which was the deadline for Germany to have signed the peace treaty. Unaware that the deadline had been extended to the 23rd, Reuter ordered the ships to be sunk at the first opportunity. On the morning of 21 June, the British fleet left Scapa Flow to conduct training maneuvers, and at 11:20 Reuter transmitted the order to his ships.[61] Markgraf sank at 16:45.[4] The British soldiers in the guard detail panicked in their attempt to prevent the Germans from scuttling the ships;[64] they shot and killed Markgraf's captain, Walter Schumann, who was in a lifeboat,[3] and an enlisted man.[65] In total, the guards killed nine Germans and wounded twenty-one. The remaining crews, totaling some 1,860 officers and enlisted men, were imprisoned.[64]

Markgraf was never raised for scrapping, unlike most of the other capital ships that were scuttled.[4] Markgraf and her two sisters had sunk in deeper water than the other capital ships, which made any salvage attempt more difficult. The outbreak of World War II in 1939 put a halt to all salvage operations, and after the war it was determined that salvaging the deeper wrecks was financially impractical.[66] The rights to future salvage operations on the wrecks were sold to Britain in 1962.[4] Owing to the fact that the steel that composed their hulls was produced before the advent of nuclear weapons, Markgraf and her sisters are among the few accessible sources of low-background steel, which has occasionally been removed for use in scientific devices.[66] Markgraf and the other vessels on the bottom of Scapa Flow are a popular dive site, and are protected by a policy barring divers from recovering items from the wrecks.[67]

Notes

Footnotes

- ↑ "SMS" stands for "Seiner Majestät Schiff", or English: His Majesty's Ship.

- ↑ German warships were ordered under provisional names. For new additions to the fleet, they were given a single letter; for those ships intended to replace older or lost vessels, they were ordered as "Ersatz (name of the ship to be replaced)". See Gröner, p. 27.

- ↑ The compass can be divided into 32 points, each corresponding to 11.25 degrees. A two-point turn to port would alter the ships' course by 22.5 degrees.

- ↑ V. E. Tarrant states that Nicator and Nestor launched four torpedoes against Grosser Kurfürst and König, though all four missed their targets. John Campbell, however, states that these two ships instead targeted Derfflinger and Lützow, and it was Moorsom that fired the four torpedoes, though at Grosser Kurfürst and Markgraf. See: Tarrant, p. 114, and Campbell Jutland, pp. 55–56, respectively.

Citations

- 1 2 3 Gröner, p. 27.

- ↑ Campbell "Germany 1906–1922", p. 36.

- 1 2 Koop & Schmolke, p. 131.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Gröner, p. 28.

- ↑ Staff, p. 27.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Staff, p. 35.

- ↑ Staff, p. 29.

- ↑ Tarrant, pp. 43–44.

- ↑ Tarrant, p. 49.

- ↑ Tarrant, p. 50.

- ↑ Staff, pp. 32, 35.

- ↑ Tarrant, p. 53.

- ↑ Tarrant, p. 54.

- ↑ Tarrant, p. 286.

- ↑ Tarrant, pp. 94–95.

- ↑ Tarrant, pp. 100–101.

- 1 2 Tarrant, p. 110.

- ↑ Tarrant, pp. 110–111.

- ↑ Tarrant, p. 116.

- ↑ Tarrant, p. 118.

- ↑ Campbell Jutland, p. 100.

- ↑ Campbell Jutland, p. 101.

- ↑ Campbell Jutland, p. 110.

- ↑ Campbell Jutland, p. 111.

- ↑ Campbell Jutland, pp. 144–145.

- ↑ Tarrant, p. 137.

- ↑ Tarrant, p. 138.

- 1 2 Campbell Jutland, pp. 152–153.

- ↑ Campbell Jutland, p. 181.

- ↑ Campbell Jutland, pp. 170–172.

- ↑ Campbell Jutland, p. 153.

- ↑ Campbell Jutland, p. 155.

- ↑ Campbell Jutland, p. 156.

- ↑ Campbell Jutland, pp. 193–195.

- ↑ Campbell Jutland, p. 162.

- ↑ Campbell Jutland, p. 204.

- ↑ Campbell Jutland, p. 206.

- ↑ Campbell Jutland, p. 245.

- ↑ Tarrant, pp. 172–174.

- ↑ Campbell Jutland, p. 201.

- 1 2 Campbell Jutland, p. 275.

- ↑ Campbell Jutland, pp. 250–251.

- ↑ Campbell Jutland, pp. 298–299.

- ↑ Campbell Jutland, pp. 300–301.

- ↑ Campbell Jutland, p. 314.

- ↑ Tarrant, pp. 246–247.

- ↑ Campbell Jutland, p. 320.

- ↑ Campbell Jutland, p. 336.

- ↑ Tarrant, p. 292.

- ↑ Tarrant, pp. 296, 298.

- ↑ Massie, p. 683.

- ↑ Preston, p. 80.

- ↑ Halpern, p. 213.

- ↑ Halpern, pp. 214–215.

- 1 2 Halpern, p. 215.

- 1 2 Staff, pp. 35–36.

- ↑ Tarrant, pp. 280–281.

- ↑ Tarrant, pp. 281–282.

- 1 2 Tarrant, p. 282.

- ↑ Herwig, p. 252.

- 1 2 Herwig, p. 256.

- ↑ Herwig, pp. 254–255.

- ↑ Herwig, p. 255.

- 1 2 Herwig, p. 257.

- ↑ Staff, p. 36.

- 1 2 Butler, p. 229.

- ↑ Konstam, p. 187.

References

- Butler, Daniel Allen (2006). Distant Victory: The Battle of Jutland and the Allied Triumph in the First World War. Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-275-99073-2.

- Campbell, John (1998). Jutland: An Analysis of the Fighting. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 978-1-55821-759-1.

- Campbell, John (1987). "Germany 1906–1922". In Sturton, Ian. Conway's All the World's Battleships: 1906 to the Present. London: Conway Maritime Press. pp. 28–49. ISBN 978-0-85177-448-0.

- Gröner, Erich (1990). German Warships: 1815–1945. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-790-6. OCLC 22101769.

- Halpern, Paul G. (1995). A Naval History of World War I. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-55750-352-7. OCLC 57447525.

- Herwig, Holger (1998) [1980]. "Luxury" Fleet: The Imperial German Navy 1888–1918. Amherst, New York: Humanity Books. ISBN 978-1-57392-286-9. OCLC 57239454.

- Konstam, Angus (2002). The History of Shipwrecks. New York City: Lyons Press. ISBN 978-1-58574-620-0.

- Koop, Gerhard; Schmolke, Klaus-Peter (1999). Von der Nassau — zur König-Klasse (in German). Bonn: Bernard & Graefe Verlag. ISBN 978-3-7637-5994-1.

- Massie, Robert K. (2003). Castles of Steel. New York City: Ballantine Books. ISBN 978-0-345-40878-5. OCLC 57134223.

- Preston, Anthony (1972). Battleships of World War I: An Illustrated Encyclopedia of the Battleships of all Nations, 1914–1918. Harrisburg, PA: Stackpole Books. ISBN 978-0-8117-0211-9. OCLC 402382.

- Staff, Gary (2010). German Battleships: 1914–1918 (Volume 2). Oxford: Osprey Books. ISBN 978-1-84603-468-8. OCLC 449845203.

- Tarrant, V. E. (2001) [1995]. Jutland: The German Perspective. London: Cassell Military Paperbacks. ISBN 978-0-304-35848-9. OCLC 48131785.