Saint-Louis-du-Louvre

| Saint Louis of the Louvre | |

|---|---|

| L’église collégiale et paroissiale Saint-Louis-du-Louvre | |

Etienne Bouhot, The Entrance to the Musee de Louvre and St. Louis Church (1822) | |

Saint Louis of the Louvre The location of Saint-Louis-du-Louvre prior to its demolition | |

| 48°51′37.6″N 2°20′6.0″E / 48.860444°N 2.335000°ECoordinates: 48°51′37.6″N 2°20′6.0″E / 48.860444°N 2.335000°E | |

| Location | Paris |

| Country | France |

| Denomination | Reformed Church of France (1791-1811) |

| Previous denomination | Roman Catholic (1187-1790) |

| History | |

| Former name(s) | L’église collégiale et paroissiale Saint-Thomas-du-Louvre |

| Authorising papal bull | 1199 |

| Founded | 1187 |

| Founder(s) | Robert I, Count of Dreux |

| Dedicated | 1744 (rededication) |

| Cult(s) present | Saint Thomas à Becket (1187-1744), Saint Louis (1744-1790) |

| Architecture | |

| Status | Collegiate church |

| Functional status | demolished |

| Architect(s) | Thomas Germain |

| Years built | 1739-1744 (rebuilt) |

| Construction cost | 50,000 Crowns |

| Demolished | 1811 |

| Administration | |

| Archdiocese | Paris |

Saint-Louis-du-Louvre, formerly Saint-Thomas-du-Louvre, was a medieval church in the 1st arrondissement of Paris located just west of the original Louvre Palace. It was founded as Saint-Thomas-du-Louvre in 1187 by Robert of Dreux as a Collegiate church. It had fallen into ruin by 1739 and was rebuilt as Saint-Louis-du-Louvre in 1744. The church was suppressed in 1790 during the French Revolution and turned over the next year for use as the first building dedicated to Protestant worship in the history of Paris, a role in which it continued until its demolition in 1811 to make way for Napoleon's expansion of the Louvre. The Reformed congregation was given l'Oratoire du Louvre as a replacement and saved the choir stalls from Saint-Louis-du-Louvre which are still in place at l'Oratoire.

History

Saint-Thomas-du-Louvre

On 8 October 1164, Thomas à Becket, the Archbishop of Canterbury, after intensifying conflict with Henry II over his efforts to reduce the power of the church through the Constitutions of Clarendon, was put on trial and convicted of various offenses by Henry in Northampton Castle. Becket proceeded to flee to France where he was welcomed and hosted for six years by Louis VII. Shortly after his return to England in 1170, Becket was famously murdered in Canterbury Cathedral and subsequently canonized in 1173.[1] In 1179, Louis VII travelled to Canterbury to pay his respects to the saint, making a donation of a gold chalice and an annual donation of 100 muids (~3,400 gallons) of wine for the celebration of the annual feast.[2]

Inspired by his brother's devotion, Robert of Dreux founded a new collegiate church, Saint-Thomas-du-Louvre, in 1187, with endowment for four canons. After Robert's death, his wife, Agnès de Baudemont, obtained confirmation of the foundation of the church from Pope Clement III in 1189. Philip Augustus provided further confirmation in 1192 by means of letters-patent with the great seal in green wax. A papal bull from Pope Innocent III in 1199 took the church, its property and clergy, under the protection of the Pope. In 1428, John VI, Duke of Brittany endowed more prebends for the church by donating the adjoining hotel, La Petite Bretagne, on the condition that the canons pray for his family. This increased the number of canons to seven, to be chosen alternately by the king and bishop.[2]

Saint-Louis-du-Louvre

By 1739 the church had fallen into ruin and Louis XV gave 50,000 crowns for it to be rebuilt. During the demolition process a portion of the church was left for the continuing use of the chapter. While the canons were performing the office the remaining structure collapsed, burying them in the ruins. This accident led to the union of the chapter with that of the neighboring Saint-Nicolas-du-Louvre, which had also been founded by Robert of Dreux and had at various times previously been united with Saint-Thomas, and the rededication of the reconstructed church to Saint Louis in 1744. In 1749, Saint-Maur-des-Fossés was also merged with the new congregation.[2]

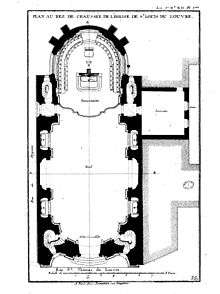

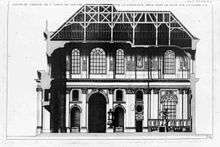

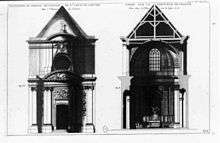

The new church was designed by Thomas Germain, known best for his work as a silversmith, and consisted of just a nave and an apse. The entrance of the church was in a circular projection decorated with Ionic pilasters. The apse housed the choir stalls of the canons surrounding the high altar. The nave was decorated with Corinthian pilasters surmounted by an entablature. In the chapel of the Virgin there was a sculpture of the Annunciation by Jean-Baptiste II Lemoyne. The church was also decorated with works by members of the families of painters, Coypel, Restout, and Van Loo. The building enjoyed a good reputation in the middle of the 18th century for its singular plan and rich internal decoration. However, the style of the exterior and portico came under some criticism.[2]

When Cardinal Fleury, the tutor and chief minister of Louis XV, died in 1743 the king decided that his mausoleum would be placed in Saint-Louis-du-Louvre. A competition was held for the commission to create the tomb, a landmark event in the history of 18th century French sculpture due to its solicitation of public input. Philibert Orry, then the director of the Royal Buildings, solicited proposals from sculptors who were members of the Royal Academy. Models for the tomb were offered by Nicolas-Sébastien Adam, Edmé Bouchardon, Charles-François Ladette, Jean-Baptiste II Lemoyne, and Jean-Joseph Vinache. The wax maquettes of proposals were displayed at the Salon for public response. Bouchardon won the competition though ultimately Lemoyne was given the commission by the family of Cardinal Fleury and the tomb remained unfinished at the time of the church's suppression.[3] The church was also home to the tomb of its architect, Thomas Germain.[4]

At the time of the French Revolution the church had a provost, a cantor, and twenty canons with the provost, cantor and fifteen canons nominated by the archbishop, four by the Duke of Penthièvre in this role as the Count of Brie, and one by Les Gallichets. On 24 February 1790, the chapter declared to the revolutionary authorities annual revenues of 98,562 livres, a great sum for the time. On 11 December 1790, municipal officers came to the church to announce to the canons the suppression of their chapter and abolition of their titles. An inventory of the objects in the church was made and all the church's properties and possessions were turned over to the state.[5]

Protestant Church

In 1791, at the behest of Jean Sylvain Bailly, the mayor of Paris, and the Marquis de Lafayette, the empty Saint-Louis-du-Louvre was rented to the newly formed Reformed congregation in Paris for the annual sum of 16,450 livres, with the first service held on Easter.[6] In 1598, Protestant worship had been forbidden in Paris by the Edict of Nantes. In 1685, the Edict of Fontainebleau made non-Catholic services illegal in all of France.[7] This inaugurated a long period of persecution for French Protestants, though some in Paris were able to worship in the chapels of the Dutch and Swedish embassies.[8]

The Edict of Tolerance in 1787 gave Protestants legal status and a congregation was formed under the pastorship of Paul-Henri Marron, who had been serving as the chaplain at the Dutch embassy. The congregation gained permission to worship openly in 1789 during the revolution and met in a variety of places including a wine shop before gaining permission to rent Saint-Louis-du-Louve, the first building dedicated to Protestant worship in the history of Paris.[9] For the dedication of the new church, or temple as French Protestants referred to their buildings, Pastor Marron preached from the text, "Soyez joyeux dans l’espérance, patients dans l’affliction, persévérants dans la prière," (be joyful in hope, patient in affliction, faithful in prayer (Romans 12:12)). When the mayor, Jean Bailly, attended in person on 13 October 1791 Marron chose the passage, "Vous connaissez la vérité et la vérité vous rendra libres," (you will know the truth, and the truth will set you free (John 8:32)).[6]

As the revolution became increasingly hostile to Christianity, Marron was arrested on 21 September 1793. He was released and then rearrested and released once more, having made the concession of having services once every ten days according to the revolutionary calendar instead of on Sundays.[6] Marron was once more arrested in June 1794 for continuing to marry and baptize in secret after Christian practice had been banned by Robespierre in favor of the Cult of the Supreme Being. He was freed from prison only by the fall of Robespierre.[10]

In the Concordat of 1801, Napoleon came to an agreement with Pope Pius VII to reconcile the Catholic church to the French state. The concordat also led to official recognition of, and state control over, other religious groups including Protestants. As a result, three former Catholic churches were dedicated for the use of reformed believers in Paris, Sainte-Marie-des-Anges, the chapel of the Pentemont Abbey, and Saint-Louis-du-Louvre. In 1806 however, Napoleon decreed an expansion of the Louvre that would require the demolition of all existing structures between the Louvre and the Tuileries Palace including the church of Saint-Louis. As a replacement the Reformed congregation was given l'Oratoire du Louvre, which had also been suppressed in the revolution. The choir and some of the other woodwork was preserved and can be seen in l'Oratoire, including the misericorde seats in the choir stalls that enabled the canons to rest while standing.[11] While most of the church was demolished in 1811, a portion remained standing until the construction of the Denon wing of the Louvre in 1850.[12]

References

- ↑ Milman, Henry Hart (1860). Life of Thomas à Becket. Sheldon & company. p. 95ff.

- 1 2 3 4 The History of Paris: From the Earliest Period to the Present Day; Containing a Description of Its Antiquities, Public Buildings, Civil, Religious, Scientific and Commercial Institutions. Paris: A. and W. Galignani. 1825. pp. 339–341.

- ↑ Weinshenker, Anne Betty (2008). A God Or a Bench: Sculpture as a Problematic Art During the Ancien Régime. Peter Lang. pp. 95–96. ISBN 978-3039105434.

- ↑ Landru, Philippe. "Eglise Saint-Thomas-du-Louvre (disparue)". Cimitières de France et d'ailleurs.

- ↑ Delarc, Odon-Jean-Marie (1895). L'Eglise de Paris pendant la Révolution française: 1789-1801. Paris: Desclée, de Brouwer et Cie. pp. 265–266.

- 1 2 3 Vassaux, Philippe. "Pasteur Paul-Henri Marron (1754 - 1832)". l'Oratoire du Louvre.

- ↑ "The Edict of Fontainebleau or the Revocation (1685)". Musée virtuel du Protestantisme.

- ↑ "Temples in Paris: Catholic churches and other places devoted to Protestant worship after the Concordat in 1801". Musée virtuel du Protestantisme.

- ↑ "1791: Installation des protestants à Saint Louis du Louvre". l'Oratoire du Louvre.

- ↑ Almanach des Protestants de l’Empire Français pour l’an de grâce 1809, Notice sur l’église actuelle de Paris, Bibliothèque du Protestantisme Français (75007, Paris), pages 259, Cote L.22864 I

- ↑ "Les Stalles". l'Oratoire du Louvre.

- ↑ Landru, Philippe. "Eglise Saint-Thomas-du-Louvre (disparue)". Cimitières de France et d'ailleurs.

External links

- An article on the church's tombs (French)

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Église Saint-Louis-du-Louvre. |