Same-sex marriage in South Africa

Same-sex marriage has been legal in South Africa since the Civil Union Act came into force on 30 November 2006. The decision of the Constitutional Court in the case of Minister of Home Affairs v Fourie on 1 December 2005 extended the common-law definition of marriage to include same-sex spouses—as the Constitution of South Africa guarantees equal protection before the law to all citizens regardless of sexual orientation—and gave Parliament one year to rectify the inequality in the marriage statutes. On 14 November 2006, the National Assembly passed a law allowing same-sex couples to legally marry 230 to 41, which was subsequently approved by the National Council of Provinces on 28 November in a 36 to 11 vote, and the law came into effect two days later.

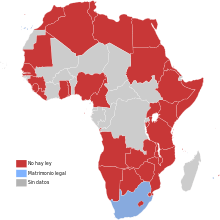

South Africa was the fifth country, the first (and only, as of October 2016) in Africa, the first in the southern hemisphere, the first republic, and the second outside Europe to legalise same-sex marriage.

History

Background

South Africa was the first country in the world to safeguard sexual orientation as a human right in its constitution.[1] Both the Interim Constitution, which came into force on 27 April 1994, and the final Constitution, which replaced it on 4 February 1997, forbid discrimination on the basis of sex, gender or sexual orientation. These equality rights formed the basis for a series of court decisions granting specific rights to couples in long-term same-sex relationships:

- Langemaat v Minister of Safety and Security (1998) recognised the reciprocal duty of support between same-sex partners, and extended medical insurance benefits.

- National Coalition for Gay and Lesbian Equality v Minister of Home Affairs (1999) extended immigration benefits to foreign partners of South African citizens.

- Satchwell v President of the Republic of South Africa (2002) extended remuneration and pension benefits.

- Du Toit v Minister of Welfare and Population Development (2002) allowed same-sex couples to adopt children jointly.

- J v Director General, Department of Home Affairs (2003) allowed both partners to be recorded as the parents of a child conceived through artificial insemination.

- Du Plessis v Road Accident Fund (2003) recognised the claim for loss of support when a same-sex partner is negligently killed.

- Gory v Kolver NO (2006) allowed inheritance of the estate of a partner who died intestate.[2]

The Fourie case

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

In 2002 a lesbian couple, Marié Fourie and Cecelia Bonthuys, with the support of the Lesbian and Gay Equality Project, launched an application in the Pretoria High Court to have their union recognised and recorded by the Department of Home Affairs as a valid marriage. Judge Pierre Roux dismissed the application on 18 October 2002, on the technical basis that they had not properly attacked the constitutionality of the definition of marriage or the Marriage Act, 1961.[3][4]

Fourie and Bonthuys requested leave to appeal to the Constitutional Court, but this was denied and the High Court instead granted leave to appeal to the Supreme Court of Appeal (SCA). They applied to the Constitutional Court for direct access, but this was denied on 31 July 2003; the court stated that the case raised complex issues of common and statutory law on which the SCA's views should first be heard.[5][6]

Fourie and Bonthuys therefore appealed the High Court judgment to the SCA, which handed down its decision on 30 November 2004. The five-judge court ruled unanimously that the common-law definition of marriage was invalid because it unconstitutionally discriminated on the basis of sexual orientation, and that it should be extended to read "Marriage is the union of two persons to the exclusion of all others for life." The court was, however, divided on the problem of the Marriage Act, which required a marriage officer to follow a formula which did not allow for same-sex marriage. The majority opinion, written by Judge Edwin Cameron, ruled that because Fourie and Bonthuys had not challenged the Marriage Act, the court could not invalidate it, and therefore their marriage could not immediately be solemnized. In a dissenting opinion, Judge Ian Farlam stated that the marriage formula followed from the common-law definition and the court should update it; on the other hand, he was of the opinion that the order of invalidity should be suspended for two years to allow Parliament to adopt its own remedy for the situation.[7][8][9]

The government appealed the SCA's ruling to the Constitutional Court, arguing that a major alteration to the institution of marriage was for Parliament and not the courts to decide, while Fourie and Bonthuys cross-appealed, arguing that the Marriage Act should be altered as Judge Farlam had suggested. In the meanwhile, the Lesbian and Gay Equality Project had also launched a separate lawsuit directly attacking the constitutionality of the Marriage Act, which was originally to be heard in the Johannesburg High Court; the Constitutional Court granted the Project's request to have it heard and decided simultaneously with the Fourie case.

On 1 December 2005 the Constitutional Court handed down its decision: the nine justices agreed unanimously that the common-law definition of marriage and the marriage formula in the Marriage Act, to the extent that they excluded same-sex partners from marriage, were unfairly discriminatory, unjustifiable, and therefore unconstitutional and invalid. In a widely quoted passage from the majority ruling, Justice Albie Sachs wrote:

"The exclusion of same-sex couples from the benefits and responsibilities of marriage, accordingly, is not a small and tangential inconvenience resulting from a few surviving relics of societal prejudice destined to evaporate like the morning dew. It represents a harsh if oblique statement by the law that same-sex couples are outsiders, and that their need for affirmation and protection of their intimate relations as human beings is somehow less than that of heterosexual couples. It reinforces the wounding notion that they are to be treated as biological oddities, as failed or lapsed human beings who do not fit into normal society, and, as such, do not qualify for the full moral concern and respect that our Constitution seeks to secure for everyone. It signifies that their capacity for love, commitment and accepting responsibility is by definition less worthy of regard than that of heterosexual couples."— Paragraph 71 of the judgment

There was some disagreement about the remedy: the majority (eight of the justices) ruled that the declaration of invalidity should be suspended for a year to allow Parliament to correct the situation, as there were different ways in which this could be done, and the Law Reform Commission had already investigated several proposals. If Parliament did not end the inequality by 1 December 2006, then words would automatically be "read in" to the Marriage Act to allow same-sex marriages. Justice Kate O'Regan dissented, arguing that these words should be read in immediately.[10][11]

The Civil Union Act

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

On 24 August 2006, the Cabinet approved the Civil Union Bill for submission to Parliament. The bill as initially introduced would only have allowed civil partnerships which would be open only to same-sex couples and have the same legal consequences as marriage. It also included provisions to recognise domestic partnerships between unmarried partners, both same-sex and opposite-sex.[12] The state law advisers, who screen laws for constitutionality and form, declined to certify the bill, suggesting that it failed to follow the guidelines laid down by the Constitutional Court. The Joint Working Group, a network of LGBTI organisations, described the idea of a separate marriage law for same-sex couples as "an apartheid way of thinking".[13]

On 16 September, thousands of South Africans took to the streets in several cities to protest same-sex marriage.[14] The minor opposition African Christian Democratic Party (ACDP) pushed for a constitutional amendment to define marriage as between a man and a woman; this was rejected by the National Assembly's portfolio committee on Home Affairs.[15] Public hearings on the Civil Union Bill began on 20 September. On 7 October, the Marriage Alliance organised a march to the Union Buildings in Pretoria to hand to government representatives a memorandum opposing same-sex marriage.

On 9 October, the governing African National Congress voted to support the Civil Union Bill. Although the party had been split on the issue, the vote meant that ANC MPs would be obliged to support the bill in Parliament. The full party support came after members of the national executive committee reminded party members that the ANC had fought for human rights, which included gay rights.

It was originally expected that the National Assembly would vote on the bill on 20 October in order to allow enough time for the National Council of Provinces to debate and vote on it ahead of the 1 December deadline. The vote was repeatedly delayed as the Portfolio Committee on Home Affairs was still involved in discussions.[16] In response to the argument that 'separate but equal' civil partnerships would not comply with the Constitutional Court's ruling, the Portfolio Committee amended the bill to allow either marriages or civil partnerships, and to allow them to both same- and opposite-sex couples. The chapter dealing with the recognition of domestic partnerships was also removed.

The amended bill was passed by the National Assembly on 14 November by 230 votes to 41, and by the National Council of Provinces on 28 November by 36 votes to 11.[17] Deputy President Phumzile Mlambo-Ngcuka, acting for President Thabo Mbeki, signed it into law on 29 November, and it became law the following day, one day before the Constitutional Court's order would otherwise have come into force.[18] The Minister of Home Affairs Nosiviwe Mapisa-Nqakula said the law was only a temporary measure, noting that a fuller marriage law would be formulated to harmonise the several pieces of marriage legislation now in force.[19][20][21]

The bill was hailed by gay and liberal activists as another step forward out of the country's apartheid past, while at the same time some clergy and traditional leaders described it as "the saddest day in our 12 years of democracy." Islamic leader Sheikh Sharif Ahmed called the bill a "foreign action imposed on Africa".[22][23]

The first couple to wed, Vernon Gibbs and Tony Halls, did so in George, the following day, 1 December 2006. They encountered no problems, and a second couple married later that day in the same location.[24]

In 2013 South Africa's first traditional gay wedding was held, for Tshepo Cameron Modisane and Thoba Calvin Sithol in the town of KwaDukuza in KwaZulu-Natal.[25]

Law

Three laws currently provide for the status of marriage in South Africa. These are the Marriage Act (Act 25 of 1961), which provides for civil or religious opposite-sex marriages; the Recognition of Customary Marriages Act (Act 120 of 1998), which provides for the civil registration of marriages solemnised according to the traditions of indigenous groups; and the Civil Union Act (Act 17 of 2006), which provides for opposite-sex and same-sex civil marriages, religious marriages and civil partnerships. A person may only be married under one of these laws at any given time.

Couples marrying in terms of the Civil Union Act may choose whether their union is registered as a marriage or a civil partnership. In either case, the legal consequences are identical to those of a marriage under the Marriage Act, except for such changes as are required by the context. Any reference to marriage in any law, including the common law, is deemed to include a marriage or civil partnership in terms of the Civil Union Act; similarly, any reference to husband, wife or spouse in any law is deemed to include a reference to a spouse or civil partner in terms of the Civil Union Act.

Restrictions

The parties to a marriage or civil partnership must be 18 or older and not already married or civilly partnered. The prohibited degrees of affinity and consanguinuity that apply under the Marriage Act also apply under the Civil Union Act;[26] thus a person may not marry his or her direct ancestor or descendant, sibling, uncle or aunt, niece or nephew, or the ancestor or descendant of an ex-spouse.[27]

Solemnisation

Marriages and civil partnerships must be solemnised by an authorised marriage officer. Government officials (primarily magistrates and Home Affairs civil servants) who are appointed as marriage officers under the Marriage Act are also able to solemnise marriages in terms of the Civil Union Act. Religious leaders may also be appointed as marriage officers under the Civil Union Act, but religious leaders appointed under the Marriage Act are not automatically able to solemnise marriages in terms of the Civil Union Act.

Government marriage officers who have an objection of conscience to solemnising same-sex marriages may note this objection in writing to the Minister of Home Affairs, and if they do so they cannot be compelled to solemnise same-sex marriages. (This provision does not apply to religious marriage officers because they are in any case not obliged to solemnise a marriage that would violate the doctrines of their religion.) Several constitutional scholars have argued that this provision is unconstitutional, representing as it does state-sanctioned discrimination in violation of the right to equality.[28][29]

Discrimination

Discrimination against same-sex couples is prohibited (as is all discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation) by section 9 of the Constitution and by the Promotion of Equality and Prevention of Unfair Discrimination Act.

Recognition of foreign unions

The Civil Union Act makes no explicit provisions for the recognition of foreign same-sex unions. As a consequence of the extension of the common-law definition of marriage, and based on the principle of lex loci celebrationis, a foreign same-sex marriage is recognised as a marriage in South African law. However, the status of foreign forms of partnership other than marriage, such as civil unions or domestic partnerships, is not clear. In a 2010 divorce case the Western Cape High Court recognised the validity of a British civil partnership as equivalent to a marriage or civil partnership in South African law.[30]

Criticism of the focus on same-sex marriage

Constitutional scholar Pierre de Vos has questioned the notion that the legalisation of same-sex marriage in South Africa represents the pinnacle of the human rights struggle of members of the LGBT community. He argues that those who are not involved in long term monogamous relationships and those who cannot come out of the closet and get married because of the threat of victimisation may not see any benefit from the legislation.[31]

Statistics

According to the South African government, over 3,000 same-sex couples had married in South Africa by mid-2010.[32] Statistics South Africa reports that a total of 3,327 marriages and civil partnerships were registered under the Civil Union Act up to the end of 2011; however, this figure only reflects marriages in which at least one of the spouses is a South African citizen or permanent resident.[33][34] Further, not all marriages under the Civil Union Act are between partners of the same sex, though most opposite-sex couples continue to marry under the 1961 Marriage Act.

The Statistics South Africa data are further broken down by province and year; they show that the majority of Civil Union Act marriages were registered in Gauteng or the Western Cape.

| Province | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eastern Cape | 0 | 41 | 30 | 24 | 29 | 38 | 37 | 54 | 253 |

| Free State | 1 | 23 | 20 | 26 | 28 | 27 | 21 | 32 | 178 |

| Gauteng | 49 | 362 | 324 | 391 | 381 | 425 | 411 | 452 | 2,795 |

| KwaZulu-Natal | 8 | 74 | 87 | 79 | 63 | 91 | 81 | 161 | 644 |

| Limpopo | 0 | 15 | 10 | 10 | 7 | 13 | 6 | 10 | 71 |

| Mpumalanga | 3 | 7 | 11 | 11 | 16 | 12 | 16 | 9 | 85 |

| North West | 2 | 6 | 5 | 9 | 3 | 11 | 10 | 28 | 74 |

| Northern Cape | 1 | 11 | 43 | 75 | 93 | 106 | 87 | 81 | 497 |

| Western Cape | 16 | 191 | 227 | 261 | 238 | 253 | 320 | 314 | 1,820 |

| Outside South Africa | 0 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 9 | 11 | 4 | 3 | 34 |

| Total | 80 | 732 | 760 | 888 | 867 | 987 | 993 | 1,144 | 6,451 |

See also

References

- ↑ Van Zyl M"journal of social Issues,Vol 67, No 2" 2011 University of Stellenbosh 335

- ↑ Du Bois, François, ed. (2007). Wille's principles of South African law (9th ed.). Cape Town: Juta & Co. pp. 367–369. ISBN 978-0-7021-6551-1.

- ↑ "High Court dismisses gay marriage bid". Mail & Guardian. 2002. Retrieved 3 July 2011.

- ↑ Fourie and Another v Minister of Home Affairs and Another [2002] ZAGPHC 1 (18 October 2002), Transvaal Provincial Division (South Africa)

- ↑ "Constitutional Court dismisses lesbian couple's application". Sapa. 31 July 2003. Retrieved 5 July 2011.

- ↑ Fourie and Another v Minister of Home Affairs and Another [2003] ZACC 11, 2003 (10) BCLR 1092 (CC), 2003 (5) SA 301 (CC) (31 July 2003), Constitutional Court (South Africa)

- ↑ "SA ruling 'may allow gay unions'". BBC News. 30 November 2004. Retrieved 6 July 2011.

- ↑ "South African ruling paves way for gay marriage". ABC News Online. AFP. 30 November 2004. Retrieved 6 July 2011.

- ↑ Fourie and Another v Minister of Home Affairs and Another [2004] ZASCA 132, 2005 (3) BCLR 241 (SCA), 2005 (3) SA 429 (SCA) (30 November 2004), Supreme Court of Appeal (South Africa)

- ↑ "Media Summary: Minister of Home Affairs and Another v Fourie and Another, Lesbian and Gay Equality Project and Eighteen Others v Minister of Home Affairs and Others" (PDF). Constitutional Court of South Africa. 1 December 2005. Retrieved 6 July 2011.

- ↑ Minister of Home Affairs and Another v Fourie and Another [2005] ZACC 19, 2006 (3) BCLR 355 (CC), 2006 (1) SA 524 (CC) (1 December 2005), Constitutional Court (South Africa)

- ↑ Quintal, Angela (25 August 2006). "Same-sex marriages bill tabled in parliament". Independent Online. Retrieved 6 July 2011.

- ↑ "'Separate law on marriage is apartheid'". Independent Online. 7 September 2006.

- ↑ "Thousands Protest Against South African Gay Marriage Bill". 365gay.com. 17 September 2006. Archived from the original on 11 March 2007. Retrieved 16 October 2009.

- ↑ "No constitutional amendment on same-sex marriages". South African Broadcasting Corporation. 16 August 2006. Archived from the original on 29 September 2007. Retrieved 16 October 2009.

- ↑ "Parliamentary committee in South Africa delays decision on civil unions". Pravda. 7 November 2006. Retrieved 14 November 2006.

- ↑ "South Africa Gay Marriage Bill Goes To President". 365Gay. 28 November 2006. Archived from the original on 26 September 2007. Retrieved 16 October 2009.

- ↑ "South Africa Gay Marriage Bill Becomes Law". 365Gay. 30 November 2006. Archived from the original on 10 December 2006. Retrieved 16 October 2009.

- ↑ "Green light for gay marriages". iafrica.com. 14 November 2006. Archived from the original on 28 December 2007. Retrieved 16 October 2009.

- ↑ "South Africa passes same-sex marriage bill". Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. 14 November 2006. Retrieved 14 November 2006.

- ↑ Nullis, Clare (14 November 2006). "South Africa Parliament OKs Gay Marriage". redOrbit. Associated Press. Retrieved 16 October 2009.

- ↑ "South Africa to legalize gay marriage". MSNBC. Associated Press. 14 November 2006. Retrieved 16 October 2009.

- ↑ Macanda, Phumza (15 November 2006). "Africans cheer, condemn SA same-sex marriage Bill". Mail & Guardian. Retrieved 16 October 2009.

- ↑ "Gay couple tie the knot in a first for South Africa". PlanetOut. Associated Press. 1 December 2006. Archived from the original on 5 January 2007. Retrieved 16 October 2009.

- ↑ "Africa's first traditional gay wedding: Men make history as they marry in full tribal costume... and say they can't wait to be parents". Dailymail.co.uk. 9 April 2013. Retrieved 5 April 2014.

- ↑ Civil Union Act 17 of 2006, s. 8(6).

- ↑ Himonga, Chuma (2007). "Part II: Persons and Family". In du Bois, François. Wille's Principles of South African Law (9th ed.). Cape Town: Juta & Co. pp. 243–244. ISBN 978-0-7021-6551-1.

- ↑ de Vos, Pierre (June 2008). "A judicial revolution? The court-led achievement of same-sex marriage in South Africa". Utrecht Law Review. 4 (2). Retrieved 31 December 2011.

- ↑ Bonthuys, Elsje (2008). "Irrational accommodation: conscience, religion and same-sex marriages in South Africa". South African Law Journal. 123 (3). Retrieved 31 December 2011.

- ↑ Steyn v Steyn [2010] ZAWCHC 224 (27 October 2010), Western Cape High Court (South Africa)

- ↑ de Vos, Pierre. "The 'inevitability' of same-sex marriage in South Africa's post-Apartheid state". South African Journal on Human Rights. 23: 432–465.

- ↑ Levin, Dan (27 July 2010). "Awaiting a Full Embrace of Same-Sex Weddings". New York Times. Retrieved 30 December 2011.

- ↑ "Statistical release P0307: Marriages and divorces, 2011" (PDF). Statistics South Africa. 10 December 2012. p. 29. Retrieved 28 December 2011.

- ↑ Statistical release P0307: Marriages and divorces, 2014

.svg.png)