Scleral lens

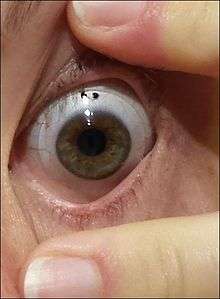

A scleral lens, also known as a scleral contact lens and ocular surface prostheses is a large contact lens that rests on the sclera and creates a tear-filled vault over the cornea. Scleral lenses are designed to treat a variety of eye conditions, many of which do not respond to other forms of treatment.

Uses

Medical uses

Scleral lenses may be used to improve vision and reduce pain and light sensitivity for people suffering from growing number of disorders or injuries to the eye, such as severe dry eye syndrome, microphthalmia, keratoconus, corneal ectasia, Stevens–Johnson syndrome, Sjögren's syndrome,[1] aniridia, neurotrophic keratitis (aneasthetic corneas), complications post-LASIK, higher order Aberrations of the eye, complications post-corneal transplant and pellucid degeneration. Injuries to the eye such as surgical complications, distorted corneal implants, as well as chemical and burn injuries also may be treated by the use of scleral lenses.[2]

Sclerals may also be used in people with eyes that are too sensitive for other smaller corneal-type lenses, but require a more rigid lens for vision correction conditions such as astigmatism.[3]

Special effects

Scleral lenses are not to be confused with "sclera" lenses, which are soft lenses and do not contain a fluid reservoir. "Sclera" lenses are used in movies such as the whited-out eyes of the monsters in Evil Dead, or blacked-out eyes in Underworld and Underworld: Evolution, or the Star Trek episode Where No Man Has Gone Before.[4] These lenses tend to be uncomfortable and sometimes impede the actors' vision, but the visual effects produced can be striking. These lenses can be custom-painted, although most companies only sell lenses with a pre-designed look.

Eye movement measurement

In experiments in ophtalmology or cognitive science, scleral lenses with embedded mirrors or with embedded magnetic field sensors in form of wire coils (called scleral coils) are commonly used for measuring eye movements.

Design

Modern scleral lenses are made of a highly oxygen permeable polymer. They are unique in their design in that they fit onto and are supported by the sclera, the white portion of the eye. The cause of this unique positioning is usually relevant to a specific patient, whose cornea may be too sensitive to support the lens directly. In comparison to corneal contact lenses, scleral lenses bulge outward considerably more. The space between the cornea and the lens is filled with artificial tears. The liquid, which is contained in a thin elastic reservoir, conforms to the irregularities of the deformed cornea, allowing vision to be restored comfortably. This helps to give the patient BCVA, or Best Corrected Visual Acuity.

Scleral lenses differ from corneal contact lenses in that they create a space between the cornea and the lens, which is filled with fluid. The prosthetic application of the lenses is to cover or "bandage" the ocular surface, providing a therapeutic environment for managing severe ocular surface disease.[5] The outward bulge of scleral lenses and the liquid-filled space between the cornea and the lens also conforms to irregular corneas and may neutralize corneal surface irregularities.[6]

Usage

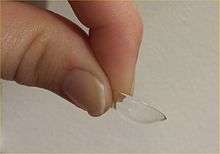

Insertion

Scleral lenses may be inserted into the eye directly from the fingers, from a hand held plunger, or from a stationary lighted plunger on a stand. Prior to inserting the scleral, the lens is over-filled with a sterile saline or other prescribed solution mixture. Some fluid is allowed to drip from the lens as it is inserted in order to ensure no bubbles become trapped under the lens after it is seated on the eye. The lens can then be rotated to the correct orientation, often denoted by a mark at the "top" of the lens, with a finger. A "left" scleral lens is often marked with two dots, and a "right" is marked with one dot.

Removal and Storage

Scleral lenses are removed using the fingers, or a small lens removal plunger. Lenses are then cleaned and sanitized before reinsertion. Scleral lenses cannot be worn while sleeping, so many wearers sanitize their lenses overnight. Unlike regular contact lenses, many sclerals can be stored dry when unused for longer periods of time.

History

A scleral lens is a prototypical lens dating back to the early 1880s. Originally these lenses were designed by using a substance to take a mold of the eye. Lenses would then be shaped to conform to the mould, initially using blown glass and then ground glass in the 1920s and polymethyl methacrylate in the 1940s.[7] Early sclerals were not oxygen permeable, which severely restricted the amount of oxygen provided to the cornea of the wearer. As such, early lenses fell into disuse until the 1970s.

Scleral lens production increased again after oxygen permeable materials, originally used in rigid gas permeable (RGP) lenses, became available for other uses. The mold building approach was replaced the use of trial kits, in which a patient tests a series of stock lenses over a course of days, weeks, or months in order to find the best fit. The recent development of digital imaging techniques has allowed some providers to evaluate and correct fit with greater accuracy. A number of scleral manufactures have also made scleral lenses with customizable points of adjustment available, so that each lens can be adjusted via a lathe to better match the contours of a single eye.

In 2008 a new digital process for manufacturing custom contoured scleral lenses was developed. This new technology uses a digital imaging device to record the shape of the surface of an eye. A virtual 3D scleral lens design is created from the information obtained. Wavefront guided and other custom optics are then imported and incorporated into the virtual lens design. The virtual design is then used manufacture a form fitted lens with high end vision correction properties.[8] This process was patented between 2008 and 2014.[9]

References

- ↑ "Sjögren's Syndrome Foundation Releases Clinical Practice Guidelines for Ocular Management in Sjögren's Patients". Sjögren’s Syndrome Foundation. Sjögren’s Syndrome Foundation. Retrieved 25 February 2016.

- ↑ Caceres, Vanessa (June 2009). "Taking a second look at scleral lenses". ASCRS EyeWorld. Retrieved 18 May 2014.

- ↑ Gemoules, Gregory. "Scleral contact lenses - explained". LaserFit. Retrieved 18 May 2014.

- ↑ http://www.scleracontactlenses.co.uk/about-lenses

- ↑ Rosenthal, Perry; Croteau, Amy (2005-05-01). "Fluid-ventilated, gas-permeable scleral contact lens is an effective option for managing severe ocular surface disease and many corneal disorders that would otherwise require penetrating keratoplasty". Eye & Contact Lens. 31 (3): 130–134. doi:10.1097/01.icl.0000152492.98553.8d. ISSN 1542-2321. PMID 15894881.

- ↑ "Excellus Health Plan, Inc - GAS PERMEABLE SCLERAL CONTACT LENS" (PDF). Excellus Health Plan, Inc. Retrieved 24 February 2016.

- ↑ Kernan, Jason. "The History and Culture of Scleral Lenses". Sclera XL. Retrieved 23 July 2015.

- ↑ Fassbender, Melissa. "Restoring sight with laser fit lenses". Medical Design Technology. Retrieved 1 January 2014.

- ↑ "Scleral Contact Lens Manufacturing". U.S. Patents. Justia Patents. Retrieved 2014-05-26.