Symmetric derivative

In mathematics, the symmetric derivative is an operation generalizing the ordinary derivative. It is defined as:

The expression under the limit is sometimes called the symmetric difference quotient.[3][4] A function is said symmetrically differentiable at a point x if its symmetric derivative exists at that point.

If a function is differentiable (in the usual sense) at a point, then it is also symmetrically differentiable, but the converse is not true. A well-known [counter]example is the absolute value function f(x) = |x|, which is not differentiable at x = 0, but is symmetrically differentiable here with symmetric derivative 0. For differentiable functions, the symmetric difference quotient does provide a better numerical approximation of the derivative than the usual difference quotient.[3]

The symmetric derivative at a given point equals the arithmetic mean of the left and right derivatives at that point, if the latter two both exist.[1][5]

Neither Rolle's theorem nor the mean value theorem hold for the symmetric derivative; some similar but weaker statements have been proved.

Examples

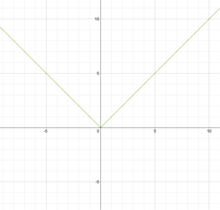

The modulus function

For the modulus function, , we have, at ,

only, where remember that and , and hence is equal to only! So, we observe that the symmetric derivative of the modulus function exists at ,and is equal to zero, even if its ordinary derivative won't exist at that point (due to a "sharp" turn in the curve at ).

Note in this example both the left and right derivatives at 0 exits, but they are unequal (one is -1 and the other is 1); their average is 0, as expected.

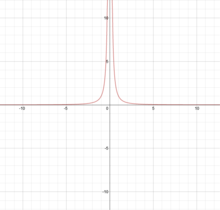

x−2

For the function , we have, at ,

only, where again, and . See that again, for this function, its symmetric derivative exists at , its ordinary derivative does not occur at , due to discontinuity in the curve at . Furthermore, neither the left nor the right derivatives are finite at 0, i.e. this is an essential discontinuity.

The Dirichlet function

The Dirichlet function, defined as:

may be analysed to realize that it has symmetric derivatives but not , i.e. symmetric derivative exists for rational numbers but not for irrational numbers.

Quasi-mean value theorem

The symmetric derivative does not obey the usual mean value theorem (of Lagrange). As counterexample, the symmetric derivative of f(x) = |x| has the image {-1, 0, 1}, but secants for f can have a wider range of slopes; for instance, on the interval [-1, 2], the mean value theorem would mandate that there exist a point where the (symmetric) derivative takes the value .[6]

A theorem somewhat analogous to Rolle's theorem but for the symmetric derivative was established by in 1967 C.E. Aull, who named it Quasi-Rolle theorem. If f is continuous on the closed interval [a, b] and symmetrically differentiable on the open interval (a, b) and f(b) = f(a) = 0, then there exist two points x, y in (a, b) such that fs(x) ≥ 0 and fs(y) ≤ 0. A lemma also established by Aull as a stepping stone to this theorem states that if f is continuous on the closed interval [a, b] and symmetrically differentiable on the open interval (a, b) and additionally f(b) > f(a) then there exist a point z in (a, b) where the symmetric derivative is non-negative, or with the notation used above, fs(z) ≥ 0. Analogously, if f(b) < f(a), then there exists a point z in (a, b) where fs(z) ≤ 0.[6]

The quasi-mean value theorem for a symmetrically differentiable function states that if f is continuous on the closed interval [a, b] and symmetrically differentiable on the open interval (a, b), then there exist x, y in (a, b) such that

As an application, the quasi-mean value theorem for f(x) = |x| on an interval containing 0 predicts that the slope of any secant of f is between -1 and 1.

If the symmetric derivative of f has the Darboux property, then the (form of the) regular mean value theorem (of Lagrange) holds, i.e. there exists z in (a, b):

- .[6]

As a consequence, if a function is continuous and its symmetric derivative is also continuous (thus has the Darboux property), then the function is differentiable in the usual sense.[6]

Generalizations

The notion generalizes to higher-order symmetric derivatives and also to n-dimensional Euclidean spaces.

The second symmetric derivative

It is defined as

If the (usual) second derivative exists, then the second symmetric derivative equals it.[8] The second symmetric derivative may exist however even when the (ordinary) second derivative does not. As example, consider the sign function which is defined through

The sign function is not continuous at zero and therefore the second derivative for does not exist. But the second symmetric derivative exists for :

See also

- Central differencing scheme

- density point

- generalized derivative

- Generalizations of the derivative

- Symmetrically continuous function

References

- 1 2 Peter R. Mercer (2014). More Calculus of a Single Variable. Springer. p. 173. ISBN 978-1-4939-1926-0.

- 1 2 Thomson, p. 1

- 1 2 Peter D. Lax; Maria Shea Terrell (2013). Calculus With Applications. Springer. p. 213. ISBN 978-1-4614-7946-8.

- ↑ Shirley O. Hockett; David Bock (2005). Barron's how to Prepare for the AP Calculus. Barron's Educational Series. p. 53. ISBN 978-0-7641-2382-5.

- ↑ Thomson, p. 6

- 1 2 3 4 5 Prasanna Sahoo; Thomas Riedel (1998). Mean Value Theorems and Functional Equations. World Scientific. pp. 188–192. ISBN 978-981-02-3544-4.

- ↑ Thomson, p. 7

- 1 2 A. Zygmund (2002). Trigonometric Series. Cambridge University Press. pp. 22–23. ISBN 978-0-521-89053-3.

- Thomson, Brian S. (1994). Symmetric Properties of Real Functions. Marcel Dekker. ISBN 0-8247-9230-0.

- A.B. Kharazishvili (2005). Strange Functions in Real Analysis, Second Edition. CRC Press. p. 34. ISBN 978-1-4200-3484-4.

- Aull, C.E.: "The first symmetric derivative". Am. Math. Mon. 74, 708–711 (1967)