Serapeum of Saqqara

The Serapeum of Saqqara is a serapeum located north west of the Pyramid of Djoser at Saqqara, a necropolis near Memphis in Lower Egypt. It was the burial place of the Apis bulls, which were incarnations of the deity Ptah. It was believed that the bulls became immortal after death as Osiris Apis, shortened to Serapis in the Hellenic period. The most ancient burials found at this site date back to the reign of Amenhotep III.

In the 13th century BCE, Khaemweset, son of Ramesses II, ordered that a tunnel be excavated through one of the mountains, with side chambers designed to contain large granite sarcophagi weighing up to 70 tonnes each, which held the mummified remains of the bulls.[1][2] A second tunnel, approximately 350 m in length, 5 m tall and 3 m wide (1,148.3×16.4×9.8 ft), was excavated under Psamtik I and later used by the Ptolemaic dynasty.

The long boulevard leading to the ceremonial site, flanked by 600 sphinxes, was likely built under Nectanebo I.

The temple was discovered by Auguste Mariette,[3] who had gone to Egypt to collect coptic manuscripts but later grew interested in the remains of the Saqqara necropolis.[4] In 1850, Mariette found the head of one sphinx sticking out of the shifting desert sand dunes, cleared the sand, and followed the boulevard to the site. After using explosives to clear rocks blocking the entrance to the catacomb, he excavated most of the complex.[5] Unfortunately, his notes of the excavation were lost, which has complicated the use of these burials in establishing Egyptian chronology.

Mariette found one undisturbed burial, which is now at the Agricultural Museum in Cairo. The other 24 sarcophagi, of the bulls, had been robbed.[6]

A controversial aspect of the Saqqara find is that for the period between the reign of Ramesses XI and the 23rd year of the reign of Osorkon II – about 250 years, only nine burials have been discovered, including three sarcophagi Mariette reported to have identified in a chamber too dangerous to excavate, which have not been located since. Because the average lifespan of a bull was between 25 and 28 years, egyptologists believe that more burials should have been found. Furthermore, four of the burials attributed by Mariette to the reign of Ramesses XI have since been retrodated. Scholars who favour changes to the standard Egyptian chronology, such as David Rohl, have argued that the dating of the twentieth dynasty of Egypt should be pushed some 300 years later on the basis of the Saqqara discovery.[7][8][9] Most scholars rebut that it is far more likely that some burials of sacred bulls are waiting to be discovered and excavated.[10][11]

- Dromos at the entrance

Sphinx of the dromos, now at the Louvre

Sphinx of the dromos, now at the Louvre- Detail of a sphinx of the dromos

Reclining lion of Nectanebo I

Reclining lion of Nectanebo I Graffiti in demotic script made by a pilgrim on the portal

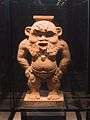

Graffiti in demotic script made by a pilgrim on the portal Statue of Bes

Statue of Bes The crypt of the Louvre

The crypt of the Louvre Statue of Apis, from a chapel of the Serapeum

Statue of Apis, from a chapel of the Serapeum

Sources and references

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Serapeum of Saqqara. |

- ↑ Mathieson, I., Bettles, E., Clarke, J., Duhig, C., Ikram, S., Maguire, L., et al. (1997). The National Museums of Scotland Saqqara survey project 1993-1995. Journal of Egyptian archaeology, 83, 17-53.

- ↑ Mathieson, I., Bettles, E., Dittmer, J., & Reader, C. (1999). The National Museums of Scotland Saqqara survey project, earth sciences 1990-1998. Journal of Egyptian archaeology, 85, 21-43.

- ↑ Malek, J. (1983). Who Was the First to Identify the Saqqara Serapeum? Chronique d'Egypte Bruxelles, 58(115-116), 65-72.

- ↑ Harry Adès, A Traveller's History of Egypt (Chastleton Travel/Interlink, 2007) ISBN 1-905214-01-4 p. 274.

- ↑ Dodson, A. (2000). The Eighteenth Century discovery of the Serapeum. KMT, 11(3), 48-53.

- ↑ Farag, Sami (1975). Two Serapeum Stelae: Egypt Exploration Society. JEA, 61, pp 165-167.

- ↑ Beechick, R. (2001). Chronology for everybody. Technical Journal, 15(3).

- ↑ Rohl, D. M. Pharaohs and kings: Crown Publishers.

- ↑ Rohl, D. M. (1992). A Test of Time: The New Chronology of Egypt and its Implications for Biblical Archaeology and History.

- ↑ Steiner, M. (1999). THE NEW CHRONOLOGY DEBATE - Problems of Synthesis - A criticism of the New Chronology from Margreet Steiner.

- ↑ Molnár, J. (2003). The liberation from Egypt and the new chronology. Sacra Scripta (1), 13.

Coordinates: 29°52′29″N 31°12′45″E / 29.87472°N 31.21250°E