The Seven Heroes and Five Gallants

Chapter 26: Bao Zheng judges a court case. (From a 1892 reprint published by Shanghai's Zhenyi shuju, collection of Fudan University.) | |

| Author | Shi Yukun (attributed) |

|---|---|

| Country | Qing dynasty |

| Language | Written Chinese |

| Genre | |

| Set in | 11th century (Song dynasty) |

| Published |

|

| Media type | |

| Followed by | The Five Younger Gallants (1890) |

| The Seven Heroes and Five Gallants | |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 七俠五義 | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simplified Chinese | 七侠五义 | ||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| The Three Heroes and Five Gallants | |||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 三俠五義 | ||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 三侠五义 | ||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| The Tale of Loyal Heroes and Righteous Gallants | |||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 忠烈俠義傳 | ||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 忠烈侠义传 | ||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

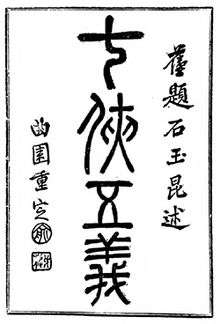

The Tale of Loyal Heroes and Righteous Gallants (忠烈俠義傳), also known by its 1883 reprint title The Three Heroes and Five Gallants (三俠五義), is a 1879 Chinese novel based on storyteller Shi Yukun's oral performances. The novel was later revised by philologist Yu Yue and republished in 1889 under the title The Seven Heroes and Five Gallants (七俠五義).

Set in 11th-century Song dynasty, the story detailed the rise of legendary judge Bao Zheng to high office, and how a group of youxia (knights-errant)—each with exceptional martial talent and selfless heroism—helped him fight crimes, oppression, corruption and rebellion. It was one of the first novels to merge the gong'an (court-case fiction) and the wuxia (chivalric fiction) genres.

Praised for its humorous narration and vivid characterizations, the novel has enjoyed huge readership: it spawned two dozen sequels by 1924 and served as the thematic model of numerous wuxia novels in the late Qing dynasty. Even in the modern era, the tales have been continuously reenacted in popular cultural mediums, including oral storytelling, operas, films and TV dramas.

Textual Evolution

Shi Yukun's Storytelling and Transcripts

Shi Yukun was a storyteller who performed in Beijing, the Qing dynasty capital, between 1810 and 1871.[1] He gained particular fame telling the legends of Song dynasty official Bao Zheng (999–1062), also known as Bao Longtu (包龍圖; "Dragon-Pattern Bao"). Shi's performances, accompanied by sanxian (lute) playing, would attract audience of thousands.[2] This story proved so popular that publishing houses and sellers began acquiring hand-written manuscripts to be circulated and sold.[3] One such copy, apparently a transcript of another storyteller's oral narratives, contained this reference of Shi (translated by Susan Blader):[4]

Let's just take Third Master Shi Yukun as an example. No matter what, I cannot outdo him in storytelling. At present, he no longer makes appearances. But, when he would go to that storytelling hall, he would tell three chapters of a story in one day and collect many tens of strings of cash. Now today his name resounds in the nine cities and there is no one who has not heard of him. I, myself, collect only one or two strings of cash a day for my storytelling, and what can they buy these days?

These early handwritten copies were known as Bao Gong An (包公案; The Cases of Lord Bao) or Longtu Gong'an (龍圖公案; The Cases of Longtu or The Cases of the Lord of the Dragon Pattern), sharing titles with 16th-century Ming dynasty collections. A later version known as Longtu Erlu (龍圖耳錄; Aural Record of Longtu), dating as early as 1867[5] and without singsong verses and nonsense remarks, was clearly written down from memory by someone who heard Shi's live performances.[6][7] Another source mentions a Xiang Leting (祥樂亭) and a Wen Liang (文良) who "would every day go and listen to the telling of the story and after returning home together write it down comparing notes."[8] Wen Liang was one of the biggest book collectors in 19th-century Beijing and clearly an elite member of the society.[9]

The Tale of Loyal Heroes and Righteous Gallants (1879)

Based on Longtu Erlu, the 120-chapter The Tale of Loyal Heroes and Righteous Gallants was printed by a movable type at the Juzhen tang (聚珍堂) in 1879, which caused a sensation in Beijing.[10] Unprecedentedly for a print Chinese novel, the oral storyteller's name Shi Yukun appeared on the title page.[11] The book also included 3 prefaces, written respectively by:

- "Bamboo-Inquiring Master" (問竹主人) who claimed to be the main contributor. He deleted some supernatural parts of Longtu Erlu. Some scholars believe this claim indicated that he was Shi Yukun himself.[12]

- "Captivated Daoist" (入迷道人), most likely a principal writer or editor. He has been identified as Wen Lin (文琳) by some scholars.[13]

- "Thought-Retiring Master" (退思主人), probably the owner of Juzhen tang or someone close.

In a 1883 reprint by Wenya zhai (文雅齋),[14] the novel was renamed to The Three Heroes and Five Gallants, with the "three heroes" being actually four people, namely Zhan Zhao the "Southern Hero", Ouyang Chun the "Northern Hero", and the Ding twins or "Twin Heroes".[15]

The Seven Heroes and Five Gallants (1889)

Years later, Suzhou-based scholar Yu Yue (1821–1907) received the book from his friend Pan Zuyin (1830–1890), president of Qing's Board of Works, who recommended it as "quite worth reading". Initially skeptical, Yu Yue was eventually so fascinated by the novel that he set out to revise it.[16]

A meticulous philologist, Yu ensured that the writing conformed to the highest standards of scholarship.[17] Most of his changes were textual and superficial, including:

- He changed the title to The Seven Heroes and Five Gallants, because he reasoned that the Ding twins being 2 people could not be considered just 1 Hero. He also considered Ai Hu, Zhi Hua and Shen Zhongyuan "heroes", even though Zhi and Shen do not have the word "hero" in their nicknames.

- He changed a character's name from Yan Chasan (顏查散) to Yan Shenmin (顏眘敏, notice how much the Chinese characters resemble each other) because he found "Chasan" too "uneducated" for someone of a scholar-official background.[18]

The only major change from Yu Yue was that he completely rewrote Chapter 1, which was previously titled "The Crown Prince is Substituted at Birth by a Scheme; the Imperial Concubine is Rescued by a Heroic and Gallant Martyr" (設陰謀臨產換太子 奮俠義替死救皇娘) and tells of a fictional story that does not follow history. Yu found the story absurd and rewrote the chapter according to the standard history book History of Song, also changing its title to "Basing Official History to Revise Longtu's Crime Cases; Employing Lord Bao to Begin the Whole Book of Heroes and Gallants" (據正史翻龍圖公案 借包公領俠義全書). However, he did not change later chapters which follow up on that substory, resulting in slight inconsistencies.[19]

Despite his pedantry, his revised version, which was published by Shanghai's Guangbaisong zhai (廣百宋齋), became the predominant version throughout China, particularly in South China.[20]

Later Reprints

By the end of the 19th century, the novel was republished at least 13 times.[14]

In the 1920s, Lu Xun (1881–1936) considered it necessary to reprint this novel. In a letter to Hu Shih (1891–1962) dated December 28, 1923, Lu suggested using the version before Yu Yue's editorship while including Yu's Chapter 1 as an appendix. The reprinting project was undertaken by Yu Yue's great-grandson Yu Pingbo (1900–1990), who nevertheless consulted his great-grandfather's version during his editorship. When East Asia Library (亞東圖書館) published the reprint in 1925, Hu wrote the preface and greatly praised the original.[21] This reprint significantly revived the The Three Heroes and Five Gallants version.

Main Characters

- Bao Zheng, also known as Judge Bao

The Seven Heroes

The Five Gallants / Five Rats

- Lu Fang, nicknamed "Sky-Penetrating Rat"

- Han Zhang, nicknamed "Earth-Piercing Rat"

- Xu Qing, nicknamed "Mountain-Boring Rat"

- Jiang Ping, nicknamed "River-Overturning Rat"

- Bai Yutang, nicknamed "Brocade-Coated Rat"

(A New Year picture originally from Yangliuqing, collection of Waseda University.)

Structure

Discussing the plot, researcher Paize Keulemans concluded, "there is no main plot. Rather, the novel's structure consists of a bewildering number of events that defy easy and succinct summary".[22] Still, the novel can be roughly divided into 2 parts, with the first 27 chapters focusing on Bao Zheng and his legal cases[23] (gong'an genre) and the remaining 93 chapters focusing on the heroes and gallants (wuxia genre). Stories from the first part were largely taken from literary and oral traditions and as such contain supernatural materials (what "Bamboo-Inquiring Master", possibly Shi Yukun himself, described as "the occasional strange and bizarre event"[24]). In comparison, the second part exclusively represents Shi's creative genius[25] and is devoid of superstition.[26]

Sequels and Imitators

The Five Younger Gallants and The Sequel to the Five Younger Gallants

The 1879 novel does not complete by the 120th and final chapter, instead, in the final page the readers are referred to a sequel book titled The Five Younger Gallants (小五義), which was said to be "close to a hundred chapters".[27] In 1890, a novel with that title was published by another Beijing publisher, Wenguang lou (文光樓). It was edited by Shi Duo (石鐸)[28] and a "Wind-Captivated Daoist" (風迷道人)—calling to mind "Captivated Daoist", the editor of the original novel.[29] Interestingly, none of the "previewed" plotlines at the end of the original was actually found in the sequel.[30] The editors did not deny that the two novels had different origins: Shi Duo claimed that their novel was published after acquiring the complete three-hundred-some-chapter "authentic" draft by Shi Yukun, "without begrudging the great cost". According to their draft, which contained 3 parts, "Wind-Captivated Daoist" believed the 1879 original must have been a fake.[31]

Despite having 124 chapters,[32] the "Copper Net Trap" that the heroes and gallants set out to destroy in the 1879 original was still not destroyed by the end of the book. Instead, the novel ends on a cliff-hanger to entice its readers to purchase the next installment, which was published in 1891 as The Sequel to the Five Younger Gallants (續小五義). Both sequels enjoyed huge readership and were reprinted many times.[33] Lu Xun believed "these works were written by many hands... resulting in numerous inconsistencies."[34]

Other Sequels and Imitators

Two alternative sequels to the original novel are:[36]

- The Sequel to the Tale of Heroes and Gallants (續俠義傳), first appeared during Guangxu Emperor's reign (1875–1908).

- The Sequel to the Seven Heroes and Five Gallants (續七俠五義), first published in 1905 by a "Master of Fragrant Grass Building" (香草館主人)

Shi Duo in his preface to The Sequel to the Five Younger Gallants denounced competitors who claimed that they possessed Shi Yukun's story as "shameless crooks".[37] Although The Sequel to the Five Younger Gallants completed the tale,[36] it could not stop enthusiasts and profiteers from writing and publishing more sequels, such as Another Sequel to the Five Younger Gallants (再續小五義), The Third Sequel to the Five Younger Gallants (三續小五義) and many others, with Lu Xun in 1924 counting 24 sequels.[34] An explosion of copycat novels also flooded the market in the last years of the 19th century, assuming similar titles such as

- The Nine Gallants and Eighteen Heroes (九義十八俠)

- The Seven Swordsmen and Thirteen Heroes (七劍十三俠)

- The Eight Elder Gallants (大八義), which was followed by The Eight Younger Gallants (小八義), A Sequel to the Eight Younger Gallants (續小八義), and Another Sequel to the Eight Younger Gallants (再續小八義)

In a 1909 essay, writer Shi An (石菴) lamented the cheapness of such works (as translated by Paize Keulemans):[38]

From the time The Seven Knights and the Five Gallants appeared, not less than one hundred imitators have followed... At first I could not understand how so much writing of this kind could suddenly appear, but later a friend told me that novels such as these are produced by Shanghai publishers who, seeking petty profits, specially hire half-educated literati to put together such books, all so as to sell them widely. Now such books as these are most suited to find favor with the lower echelons of society, so [the publishers] just change the title a bit and thus produce yet another novel, and as a result a thousand—no, ten thousand—volumes appear. These novels are like the feet of peasant women: they're both long and smelly, filling the streets and avenues, they appear everywhere.

(From a 1890 reprint published by Shanghai's Guangbaisong zhai, collection of Fudan University.)

Translations

Two English translations are available:

- Song Shouquan (translator) (1997). The Seven Heroes and Five Gallants. Chinese Literature Press. ISBN 7-5071-0358-7.

- Blader, Susan (1998). Tales of Magistrate Bao and His Valiant Lieutenants: Selections from Sanxia Wuyi. The Chinese University Press. ISBN 962-201-775-4.

Song's book is an abridged translation of all 120 chapters. Blader translated roughly a third of the chapters, relatively more faithfully. As Blader used the version before Yu Yue's editorship, Chapter 1 is noticeably different from Song's book.

In addition, two other books contain (largely rewritten) stories from the novel's first 19 chapters:

- Chin, Yin-lien C.; Center, Yetta S.; Ross, Mildred (1992). "The Stone Lion" and Other Chinese Detective Stories: The Wisdom of Lord Bau. M. E. Sharpe. ISBN 0-87332-634-2.

- Hu Ben; Sun Haichen (translator) (1997). Exchanging a Leopard Cat for a Prince: Famous Trials Conducted by Lord Bao. Foreign Languages Press. ISBN 7-119-01896-5.

The novel has been translated into other languages, such as Japanese (by Torii Hisayasu),[39] Vietnamese (by Phạm Văn Điều),[40] Malay (by Oey Kim Tiang),[41] French (by Rébecca Peyrelon),[42][43][44] and Russian (by Vladimir A. Panasyuk).[45]

Themes

The novel places great emphasis on Confucian values, such as yi (righteousness) and ren (altruism), which characterize all heroes and gallants. In Chapter 13, the storyteller added a short commentary on the definition of "hero" (translated by Susan Blader):[46]

Zhan Zhao is truly a practitioner of good deeds and righteous acts. He feels at ease everywhere. It isn't really that he must eradicate all evils, but once he sees an injustice he cannot leave it alone. It is as though it becomes his own personal affair and that, precisely, is why he is worthy of the name "Hero".

In addition, the novel also champions personal freedom. In Chapter 29, for example, Zhan Zhao confessed (as translated by Song Shouquan): "As to my promotion to the imperial guard, I find it prevents me from doing what I like best and that is travel around enjoying the beauties of nature. Now I'm tied down by officialdom. If it wasn't for the high regard I have for Prime Minister Bao I would have resigned long ago." His "northern" counterpart Ouyang Chun even shunned Bao and other officials altogether, preferring to help the government on his own, even anonymously. In imperial China, when officialdom was particularly prized and coveted, such statements and actions speak volumes of the author's beliefs.

The last 42 chapters[23] focus on the suppression of a fictitious rebellion. The inclusion of this segment conveyed the author's desire for peace and tranquility, as mid-19th century Qing dynasty was ravaged by numerous bloody rebellions, including the Taiping Rebellion, the Nien Rebellion, and the Panthay Rebellion, which together took tens of millions of lives.[47]

Reception

Many 20th-century literary critics also held the novel in high regard. Lu Xun considered the book "outstanding" among "storytelling tales",[48] praising the novel: "Though some of the incidents are rather naive, the gallant outlaws are vividly presented and the descriptions of town life and jests with which the book is interspersed add to the interest."[49] Hu Shih, who favorably compared the characterizations of Jiang Ping and Zhi Hua to those of Aramis and d'Artagnan in Alexandre Dumas' The Three Musketeers,[21] even included this novel among his "National Book List of the Lowest Level" (最低限度的國學書目; i.e. must-read list) for Tsinghua University students.[50] C. T. Hsia commended the language as "a vivid colloquial style that deserves the appellation of 'real pai-hua'..."[51]

Adaptations

Storytelling

Chinese masters including Wang Shaotang (1889–1968) and Shan Tianfang (born 1935) have performed stories from the novel.[14]

Films

Note: Most of the early films were opera films.

- Redress a Grievance (烏盆記), a 1927 Chinese film.

- Brocaded Mouse (錦毛鼠白玉堂), a 1927 Chinese film.

- Five Mice Make Troubles in Capital (五鼠鬧東京), a 1927 Chinese film.

- The Case of Lost Baby-Prince (狸貓換太子), a 1927 Chinese film.

- Azure-Cloud Palace (碧雲宮), a 1939 Chinese film.

- Breaking Through the Bronze Net (大破銅網陣), a 1939 Hong Kong film.

- Judge Pao vs the Eunuch (狸貓換太子包公夜審郭槐), a 1939 Hong Kong film.

- The Five Swordsmen's Nocturnal Tryst (小五義夜探沖霄樓), a 1940 Hong Kong film.

- The Furry Rat (俠盜錦毛鼠), a 1941 Hong Kong film.

- The Haunt of the Eastern Capital (五鼠鬧東京), a 2-part 1948 Hong Kong film.

- The Fight Between the Honourable Cat and Rat (御貓大戰錦毛鼠), a 1948 Hong Kong film.

- The Junior Hero Ngai Fu (小俠艾虎), a 1949 Hong Kong film.

- The Battle Between the Five Rats and the Flowery Butterfly (五鼠大戰花蝴蝶), a 1950 Hong Kong film.

- Solving the Copper-Netted Trap (大破銅網陣), a 1950 Hong Kong film.

- The Three Battles Between White Eye-Brows and White Chrysanthemum (白眉毛三戰白菊花), a 1950 Hong Kong film.

- Five Little Heroes (小五義), a 1951 Hong Kong film.

- Judge Pao's Night Trial of Kwok Wai (包公夜審郭槐), a 1951 Hong Kong film.

- Judge Pao's Night Trial of the Wicked Kwok Wai (生包公夜審奸郭槐), a 1952 Hong Kong film.

- Adventure of the Five Rats at the Hundred-Flower Tower (五鼠大鬧百花樓), a 1953 Hong Kong film.

- The Burning of Azure-Cloud Palace (火燒碧雲宮), a 1955 Hong Kong film.

- Racoon for a Prince (狸貓換太子), a 1955 Hong Kong film.

- Substituting a Racoon for the Crown Prince (狸貓換太子), a 1958 Hong Kong film.

- Shattering the Copper Net Array (大破銅網陣), a 1959 Hong Kong film.

- Tower of Traps (七俠五義夜探沖霄樓), a 1959 Hong Kong film.

- The Royal Cat and His Opponent (御貓大戰錦毛鼠), a 1963 Hong Kong film.

- The Five Rats' Adventures in the Eastern Capital (五鼠鬧東京), a 1964 Hong Kong film.

- Inside the Forbidden City (宋宮秘史), a 1965 Hong Kong film.

- King Cat (七俠五義), a 1967 Hong Kong film.

- Majesty Cat (南俠展昭), a 1975 Taiwanese film.

- The Wrongly Killed Girl (南俠展昭大破地獄門), a 1976 Taiwanese film.

- House of Traps (沖霄樓), a 1982 Hong Kong film.

- Cat vs Rat (御貓三戲錦毛鼠), a 1982 Hong Kong film.

- The Invincible Constable (御貓愛上錦毛鼠), a 1993 Hong Kong film.

- Love & Sex in Sung Dynasty (宋朝風月), a 1999 Hong Kong film.

- Cat and Mouse (老鼠愛上貓), a 2003 Hong Kong film.

- A Game of Cat and Mouse (包青天之五鼠鬥御貓), a 2005 Chinese film.

Television series

- The Seven Heroes and Five Gallants (七俠五義), a 1972 Taiwanese TV series.

- The Secret History of the Song Palace (宋宮秘史), a 1974 Taiwanese TV series.

- Justice Pao (包青天), a 1974–1975 Taiwanese TV series.

- The Five Younger Gallants (小五義), a 1977 Hong Kong TV series.

- The Five Tiger Generals (五虎將), a 1980 Taiwanese TV series.

- The Iron-Faced Judge (鐵面包公), a 1984 Hong Kong TV series.

- Exchanging A Wild Cat for the Crown Prince (狸貓換太子), a 1984 Taiwanese TV series.

- The New Seven Heroes and Five Gallants (新七俠五義), a 1986 Taiwanese TV series.

- Lord Bao (包公), a 1987 Chinese TV series.

- The New Five Younger Gallants (新小五義), a 1987 Hong Kong TV series.

- The Three Heroes and Five Gallants (三俠五義), a 1991 Chinese TV series.

- Justice Pao (包青天), a 1993 Taiwanese TV series.

- Conspiracy of the Eunuch (南俠展昭), a 1993 Hong Kong TV series.

- Young Justice Bao (俠義包公), a 1994 Singaporean TV series.

- The Seven Heroes and Five Gallants (七俠五義), a 1994 Taiwanese TV series.

- The Bold and the Chivalrous (俠義見青天), a 1994 Taiwanese TV series.

- The White-Eyebrowed Hero (白眉大俠), a 1994 Chinese TV series.

- Justice Pao (包青天), a 1994 Hong Kong TV series.

- Heroic Legend of the Yang's Family (碧血青天楊家將) and The Great General (碧血青天珍珠旗), two 1994 Hong Kong TV series

- The New Seven Heroes and Five Gallants (新七俠五義), a 1994 Chinese TV series.

- Heavenly Ghost Catcher (天師鍾馗), a 1994–1995 Singaporean TV series. Bao Zheng and related characters appear in the segments "Lord Bao Invites Zhong Kui Thrice" (包公三請鍾馗) and "Meeting Justice Bao Thrice" (三會包青天).

- Justice Pao (包青天), a 1995 Hong Kong TV series produced by TVB.

- Justice Pao (新包青天), a 1995 Hong Kong TV series produced by Asia Television.

- Return of Judge Bao (包公出巡), a 2000 Taiwanese TV series.

- Lord Bao's Life and Death Calamity (包公生死劫), a 2000 Chinese TV series.

- The Young Detective (少年包青天), a 2000–2002 Chinese TV series.

- Justice Pao (壯志凌雲包青天), a 2004 Chinese TV series.

- The New Case of Executing Chen Shimei (新鍘美案), a 2004 Chinese TV series.

- The Song Dynasty Stunning Legend (大宋驚世傳奇), a 2004 Chinese TV series.

- The Top Inkstone in the World (硯道), a 2004 Chinese TV series.

- Struggle for Imperial Power (狸貓換太子傳奇), a 2005 Chinese TV series.

- Bai Yutang (江湖夜雨十年燈—白玉堂), a 2005 Chinese TV series.

- Take Wine to Ask the Sky (把酒問青天), a 2007 Chinese TV series.

- Justice Bao (新包青天), a 2008 Chinese TV series.

- The Great Hero Di Qing (大英雄狄青), a 2009 Chinese animation TV series.

- The Black-Faced Great Lord Bao (黑臉大包公), a 2009 Chinese animation TV series.

- Justice Bao (包青天), a 2010–2012 Chinese TV series.

- Qin Xianglian (秦香蓮), a 2011 Chinese TV series.

- Invincible Knights Errant (七俠五義人間道), a 2011 Chinese TV series.

- Female Constable (带刀女捕快), a 2011 Chinese TV series.

- The Legend of Zhong Kui (鍾馗傳說), a 2012 Chinese TV series. Zhan Zhao appears in the segment "Ruthlessly Executing Demons" (除魔無情斬).

- Sleek Rat, the Challenger (白玉堂之局外局), a 2013 Chinese TV series.

- The Legend of Chasing Fish (追魚傳奇), a 2013 Chinese TV series.

- Always and Ever (情逆三世緣), a 2013 Hong Kong TV series.

- Detective Judge (神探包青天), a 2015 Chinese TV series.

- The Tiger Guillotine (虎頭鍘), a 2015 Chinese TV series.

- The Three Heroes and Five Gallants (五鼠鬧東京), an upcoming Chinese TV series.

- Hot and Spicy Bai Yutang (麻辣白玉堂), an upcoming Chinese TV series.

- Legends of Bai Yutang's Crime Cases (白玉堂探案傳奇), an upcoming Chinese TV series.

- Kaifeng Tribunal (開封府), an upcoming Chinese TV series.

In addition, two TV series set in the Qing dynasty imagined how the novel was created:

- The Strange Cases of Lord Shih (施公奇案), a 1997 Taiwanese TV series. Case 11, "Odd Happenings in Examination Halls" (考場怪譚) stars Hou Kuan-chun as Shi Yukun.

- Thirteen Sons of Heaven Bridge (天橋十三郎), a 2004 Chinese TV series, starring Xu Zheng as Shi Yukun.

See also

- Generals of the Yang Family, Chinese legends also set during 11th-century Song dynasty

- The Three Sui Quash the Demons' Revolt, a 16th-century Chinese novel also set during 11th-century Song dynasty

Notes and References

- ↑ Blader 1998, p. xxiv.

- ↑ Deng and Wang, p. 13.

- ↑ Blader 1998, p. xx.

- ↑ Blader 1998, p. xxi.

- ↑ Keulemans 2014, p. 163.

- ↑ Deng and Wang, p. 14. Longtu Erlu was not published until 1982, according to Blader 1987, p. 153.

- ↑ Blader 1998, p. xxii.

- ↑ Keulemans 2014, p. 72.

- ↑ Keulemans 2014, p. 86.

- ↑ Deng and Wang, p. 15.

- ↑ Keulemans 2014, p. 82.

- ↑ Deng and Wang, pp. 14–15.

- ↑ Keulemans 2014, p. 73.

- 1 2 3 Keulemans 2014, p. 26.

- ↑ Deng and Wang, pp. 16–17, argued, "'Three... and five...' is idiomatic usage in Chinese. In its original sense, it denotes the numerals three and five, like the 'three sage kings and five emperors' of ancient China. Used connotatively, 'three... and five...' mean 'many' or 'numerous'... Even in its original sense, it is correct to count the Southern Hero, Northern Hero and Twin Heroes as three heroes instead of four. We have 'three virtuous kings' in ancient Chinese history: King Yu of the Xia Dynasty, King Tang of the Shang Dynasty and Kings Wenwang and Wuwang of the Zhou Dynasty. They are four kings, not three. But Kings Wenwang and Wuwang both belong to the Zhou Dynasty, so they are counted as one and not two... The usage of 'three... and five...' reveals the richness of Chinese culture. 'Seven Heroes and Five Gallants' is technically correct but less imaginative."

- 1 2 Keulemans 2014, pp. 54-56.

- ↑ Keulemans 2014, p. 64.

- ↑ Because "Shen" (眘) is a rare Chinese character not recognized by most people, Yan Shenmin is often mispronounced as Yan Chunmin (顏春敏) in operas, films (e.g. House of Traps) and TV series (e.g. the 1974 Taiwanese series Justice Pao), as "Shen" appears somewhat similar to the character "Chun" (春). He has also been called Yan Renmin (顏仁敏, as in the 1994 Chinese TV adaptation), also see Blader 1987, p. 154.

- ↑ Deng and Wang, p. 16.

- ↑ Lu, p. 418.

- 1 2 Hu Shih, "Preface to The Three Heroes and Five Gallants" (三俠五義序), 15 March 1925

- ↑ Keulemans 2014, p. 10.

- 1 2 Deng and Wang, p. 18.

- ↑ Susan 1999, p. 168.

- ↑ Blader 1998, p. xvii.

- ↑ The only bizarre story in the second part is similar to the European "Lady with the Ring" tale — a girl waking up in her coffin after a visit by a grave robber (Chapter 37). However, accidental premature burial has been documented even in modern days.

- ↑ Keulemans 2014, p. 104.

- ↑ Keulemans 2014, pp. 70-71.

- ↑ Keulemans 2014, p. 87.

- ↑ Keulemans 2014, p. 105.

- ↑ Keulemans 2014, pp. 86–88.

- ↑ Keulemans 2014, p. 169.

- ↑ Keulemans 2014, pp. 70, 173.

- 1 2 Lu, p. 349.

- ↑ 書的“續集”

- 1 2 Keulemans 2014, p. 175.

- ↑ Keulemans 2014, p. 174.

- ↑ Keulemans 2014, pp. 60–61.

- ↑ "三俠五義 (Sankyō gogi)". WorldCat. Retrieved 2015-05-13.

- ↑ "Thất hiệp ngũ nghîa". WorldCat. Retrieved 2015-05-13.

- ↑ "Tjit hiap ngoe gie". WorldCat. Retrieved 2015-05-13.

- ↑ "Les plaidoiries du Juge Bao". WorldCat. Retrieved 2015-05-13.

- ↑ "Le juge Bao et l'impératrice du silence". WorldCat. Retrieved 2015-05-13.

- ↑ "Le duel des héros ; / Les plaidoiries du Juge Bao". WorldCat. Retrieved 2015-05-13.

- ↑ "Трое храбрых, пятеро справедливых (Troe khrabrykh, piatero spravedlivykh)". WorldCat. Retrieved 2015-05-13.

- ↑ Blader 1998, p. 47.

- ↑ Blader 1998, p. xiv-xvi.

- ↑ Blader 1998, xxviii.

- ↑ Lu, p. 342-343.

- ↑ "胡適晚年讀書"不要命":經搶救保命後看報" [Hu Shih's "Daredevil" Reading in His Later Years: Reading Newspapers After Life Saved]. International Daily News. 22 October 2014.

- ↑ Blader 1998, xxiv.

- Blader, Susan (1987). "'Yen Ch'a-san Thrice Tested': Printed Novel to Oral Tale". In Le Branc, Charles; Blader, Susan. Chinese Ideas About Nature and Society: Studies in Honour of Derk Bodde. Hong Kong University Press. pp. 153–173. ISBN 962-209-188-1.

- Blader, Susan (1998). Tales of Magistrate Bao and His Valiant Lieutenants: Selections from Sanxia Wuyi. The Chinese University Press. ISBN 962-201-775-4.

- Blader, Susan (1999). "Oral Narrative and Its Transformation into Print: The Case of Bai Yutang". In Børdahl, Vibeke. The Eternal Storyteller: Oral Literature in Modern China. RoutledgeCurzon. pp. 161–180. ISBN 0-7007-0982-7.

- Deng Shaoji; Wang Jun (2005). "Preface". The Seven Heroes and Five Gallants. Translated by Wen Jingen. Foreign Languages Press. pp. 13–21. ISBN 7-119-03354-9.

- Keulemans, Paize (2014). Sound Rising from the Paper: Nineteenth-Century Martial Arts Fiction and the Chinese Acoustic Imagination. Harvard University Asia Center. ISBN 978-0-674-41712-0.

- Keulemans, Paize (2007). "Listening to the Printed Martial Arts Scene: Onomatopoeia and the Qing Dynasty Storyteller's Voice". Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies. 67 (1): 51–87.

- Lu Hsun; (trans. Yang Hsien-yi and Gladys Yang) (1959) [1930]. A Brief History of Chinese Fiction. Foreign Languages Press.

- Wang, David Der-wei (1997). Fin-de-siècle Splendor: Repressed Modernities of Late Qing Fiction, 1849–1911. Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-2845-3.