Slab pull

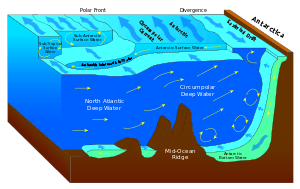

Slab pull is the portion of motion of a tectonic plate that can be accounted for by its subduction. Plate motion is partly driven by the weight of cold, dense plates sinking into the mantle at trenches.[1][2] This force and slab suction account for almost all of the force driving plate tectonics. The ridge push at rifts contributes only 5 to 10%.[3]

Carlson et al. (1983) in Lallemandet al. (2005) defines the slab pull force as:

Where:

- K is 4.2g (gravitational acceleration = 9.81 m/s2) according to McNutt (1984);

- Δρ = 80 kg/m3 is the mean density difference between the slab and the surrounding asthenosphere;

- L is the slab length calculated only for the part above 670 km (the upper/lower mantle boundary);

- A is the slab age in Ma at the trench.

The slab pull force manifests itself between two extreme forms:

- The aseismic back-arc extension as in the Izu-Bonin-Mariana Arc.

- And as the Aleutian and Chile tectonics with strong earthquakes and back-arc thrusting.

Between these two examples there is the evolution of the Farallon plate: from the huge slab width with the Nevada, the Sevier and Laramide orogenies; the Mid-Tertiary ignimbrite flare-up and later left as Juan de Fuca and Cocos plates, the Basin and Range Province under extension, with slab break off, smaller slab width, more edges and mantle return flow.

Some early models of plate tectonics envisioned the plates riding on top of convection cells like conveyor belts. However, most scientists working today believe that the asthenosphere does not directly cause motion by the friction of such basal forces. The North American Plate is nowhere being subducted, yet it is in motion. Likewise the African, Eurasian and Antarctic Plates. The subducting slabs around the Pacific Ring of Fire cool down the Earth and its Core-mantle boundary, around the African Plate the upwelling mantle plumes from the Core-mantle boundary produce rifting. The overall driving force for plate motion and its energy source remain subjects of ongoing research.

References

- Schellart, W. P.; Stegman, D. R.; Farrington, R. J.; Freeman, J.; Moresi, L. (16 July 2010). "Cenozoic Tectonics of Western North America Controlled by Evolving Width of Farallon Slab". Science. 329 (5989): 316–319. Bibcode:2010Sci...329..316S. doi:10.1126/science.1190366. PMID 20647465.

- "Breakthrough Achieved in Explaining Why Tectonic Plates Move the Way They Do". ScienceDaily. 17 July 2010.

- Conrad CP, Lithgow-Bertelloni C (2002). "How Mantle Slabs Drive Plate Tectonics". Science. 298 (5591): L45. Bibcode:2002Sci...298..207C. doi:10.1126/science.1074161. PMID 12364804.

- Clinton P. Conrad; Susan Bilek; Carolina Lithgow-Bertelloni (2004). "Great earthquakes and slab pull: interaction between seismic coupling and plate-slab coupling" (PDF). Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 218: 109–122. Bibcode:2004E&PSL.218..109C. doi:10.1016/S0012-821X(03)00643-5.

- Lallemand, S., A. Heuret, and D. Boutelier (2005). "On the relationships between slab dip, back-arc stress, upper plate absolute motion, and crustal nature in subduction zones" (PDF). Geochemistry Geophysics Geosystems. 6: Q09006. Bibcode:2005GGG.....609006L. doi:10.1029/2005GC000917.

- McNutt, M. K. (1984). "Lithospheric flexure and thermal anomalies". J. Geophys. Res. 89: 11,180–11,194. Bibcode:1984JGR....8911180M. doi:10.1029/JB089iB13p11180.

- Carlson, R. L., T. W. C. Hilde, and S. Uyeda (1983). "The driving mechanism of plate tectonics: Relation to age of the lithosphere at trench". Geophys. Res. Lett. 10: 297–300. Bibcode:1983GeoRL..10..297C. doi:10.1029/GL010i004p00297.

- ↑ Conrad CP, Lithgow-Bertelloni C (2002)

- ↑ "Plate tectonics, based on 'Geology and the Environment', 5 ed; 'Earth', 9 ed" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on July 11, 2011.

- ↑ Conrad CP, Lithgow-Bertelloni C (2004)