Slacklining

Slacklining refers to the act of walking or balancing along a suspended length of flat webbing that is tensioned between two anchors. Slacklining is similar to slack rope walking and tightrope walking. Slacklines differ from tightwires and tightropes in the type of material used and the amount of tension applied during use. Slacklines are tensioned significantly less than tightropes or tightwires in order to create a dynamic line which will stretch and bounce like a long and narrow trampoline. Tension can be adjusted to suit the user, and different webbing may be used in various circumstances. Slacklining is popular due to its simplicity and versatility;[1] it can be used in various environments with few components.

Slackline setup

Slacklines can be set up in two principal ways: in two sections of webbing with a tensioner or with three sections of webbing and a tensioner.

Two-section setup

The two-section setup consists of: a long (30–100-foot, 9–30-metre) piece of two-or-one-inch (5.1 or 2.5 cm) webbing with a loop sewn on one end, allowing it to cinch tightly around a tree. The second section is typically much shorter (10 ft, 3 m) and has a similar sewn loop on one end, allowing it to cinch around a tree while the other end of this shorter piece of webbing is sewn to a ratchet. The ratchet allows these two sections of webbing to be connected and tensioned to the user's specifications.

Three-section setup

The three-section setup consists of: a long section of webbing (30–100 ft, 9–30 m) strung tightly and connected to two shorter sections (8–12 ft, 2.5–3.5 m) that are called "tree slings" and are used as anchors on either end. The most difficult and widely discussed element of a slackline setup is the tensioning system. Common setups include simple friction methods (which can also be set up with a single section of webbing),[2] using wraps of webbing between two carabiners, a ratchet, a comealong, a carabiner pulley system,[3][4] a roped pulley system, or a commercial slackline kit.

Tree anchors

The most common anchors for slacklines are trees. Trees greater than 12 inches (30 cm) in diameter are considered ideal in most cases. There are several very effective methods of tree protection that function on two principles: eliminating abrasion, and redistributing the load over a wider area. One of the most effective means of tree protection is a wrap of vertical blocks (1 in × 1 in (2.5 cm × 2.5 cm) cut into 6 in (15 cm) pieces) strung together by drilling a small-diameter hole through the center and running cord through them. Blocks are spaced evenly to prevent the anchor slings from contacting and abrading the outer bark, and the length of the blocks distributes the load vertically as opposed to horizontally, compressing a continuous line around the trunk. The addition of a carpet square between the block wrap and the outer bark is considered ideal among the founding community of slackliners. Many other ways to protect the tree are commonly used, such as towels, mats, cardboard, carpet and purpose-made tree protectors.

Using carpet squares or cardboard even, by themselves, addresses only abrasion, leaving the load concentrated on a small area of the tree. These methods are adequate for occasional use, but with the high tension of longlines, one who slacklines regularly should take every precaution to protect the life of the tree.

Variations

A special characteristic of slacklining is the ease with which the dynamics of the practice can be altered. Using narrow (5⁄8 inch, 1.6 cm) webbing will result in a stretchier slackline. This allows for more sway in the line and can make a short line feel substantially longer. Wider webbing (2 inches, 5 cm) is much more rigid, often creating a bouncier slackline optimal for aerial tricks. The tension of the line will also increase or decrease the sway of the line. Weight due to the different methods of tensioning will also vary the performance of a slackline. A comealong and a ratchet will both add enough weight to allow the feedback from quick movements on shorter slacklines to be felt.

Styles of slacklining

Urbanlining

Urbanlining or urban slacklining combines all the different styles of slacklining. It is practiced in urban areas, for example in city parks and on the streets. Most urban slackliners prefer wide 2-inch (5 cm) lines for tricklining on the streets, but some may use narrow (5⁄8 or 1 inch, 1.6 or 2.5 cm) lines for longline purposes or for waterlining. Also see the other sections of slackline styles below.

One type of urbanlining is timelining, where one tries to stay on a slackline for as long as possible without falling down. This takes tremendous concentration and focus of will, and is a great endurance training for postural muscles.

Another type of urbanlining is streetlining, which combines street workout power moves with the slackline's dynamic, shaky, bouncy feeling. Main focus are static handstands, super splits — hands and feet together, planche, front lever, back lever, one arm handstand and other interesting extreme moves that are evolving in street workout culture.

Tricklining

Tricklining has become the most common form of slacklining due to the easy setup of 2-inch (5 cm) slackline kits. Tricklining is often done low to the ground but can be done on highlines as well. A great number of tricks can be done on the line, and because the sport is fairly new, there is plenty of room for new tricks. Some of the basic tricks done today are walking,[5] walking backwards, turns, drop knee, running and jumping onto the slackline to start walking, and bounce walking. Some intermediate tricks include: Buddha sit, sitting down, lying down, cross-legged knee drop, surfing forward, surfing sideways, and jump turns, or "180s." Some of the advanced tricks are: jumps,[6] tree plants, jumping from line-to-line, 360s, butt bounces, and chest bounces. With advancements in webbing technology & tensioning systems, the limits for what can be done on a slackline are being pushed constantly. It is not uncommon to see expert slackliners incorporating flips and twists into slackline trick combinations.

Waterlining

Waterlining is slacklining over water. This is an ideal way to learn new tricks, or to just have more fun. Common places to set up waterlines are over pools, lakes, rivers, creeks, between pier or railroad track pillars, and boat docks. The slackline can be set up high over the surface of the water, close to the surface or even underneath the surface. It is important, however, that the water be deep enough, free from obstacles, and that the area should not be travelled by boats.

Highlining

Highlining is slacklining at elevation above the ground or water. Many slackliners consider highlining to be the pinnacle of the sport. Highlines are commonly set up in locations that have been used or are still used for Tyrolean traverse. When rigging highlines, experienced slackers take measures to ensure that solid, redundant and equalized anchors are used to secure the line into position. Modern highline rigging typically entails a mainline of webbing, backup webbing, and either climbing rope or amsteel rope for redundancy. However, many highlines are rigged with a mainline and backup only, especially if the highline is low tension (less than 900 lbf (410 kgf; 4,000 N)), or rigged with high quality webbing like Type 18 or MKII Spider Silk. It is also common to pad all areas of the rigging which might come in contact with abrasive surfaces. To ensure safety, most highliners wear a climbing harness or swami belt with a leash attached to the slackline itself. Leash-less, or "free-solo" slacklining – a term borrowed from rockclimbing – is not unheard of, however, with proponents such as Dean Potter and Andy Lewis.[7]

Slackline yoga

Slackline yoga takes traditional yoga poses and moves them to the slackline. It has been described as "distilling the art of yogic concentration". To balance on a 1-inch (2.5 cm) piece of webbing lightly tensioned between two trees is not easy, and doing yoga poses on it is even more challenging. The practice simultaneously develops focus, dynamic balance, power, breath, core integration, flexibility, and confidence. Using standing postures, sitting postures, arm balances, kneeling postures, inversions and unique vinyasa, a skilled slackline yogi is able to create a flowing yoga practice without ever falling from the line.

Slackline yoga has been covered in The Wall Street Journal,[8] Yoga Journal[9] and Climbing Magazine.[10]

Freestyle slacklining

Freestyle slacklining (a.k.a. “rodeo slacklining") is the art and practice of cultivating balance on a piece of rope or webbing draped slack between two anchor points, typically about 15 to 30 feet (4.6 to 9.1 m) apart and 2 to 3 feet (60 to 90 cm) off the ground in the center. This type of very "slack" slackline provides a wide array of opportunities for both swinging and static maneuvers. A freestyle slackline has no tension in it, while both traditional slacklines and tightropes are tensioned. This slackness in the rope or webbing allows it to swing at large amplitudes and adds a different dynamic. This form of slacklining first came into popularity in 1999, through a group of students from Colby College in Waterville, Maine. It was first written about on a website called the "Vultures Peak Center for Freestyle and Rodeo Slackline Research" in 2004. The article "Old Revolution — New Recognition - 3-10-04" describes these early developments in detail.

Windlining

Windlining is a practice of slacklining performed in very windy conditions. Depending on the intensity of the wind, it can be difficult to remain on the line without being blown off. The sensation one experiences is like flying as the slacker must angle his body and arms in an aerodynamic manner to maintain balance.

History

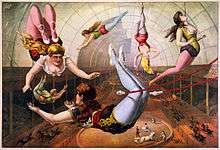

While rope walking has been around in one manner or another for thousands of years, the origins of modern-day slacklining is generally attributed to a young rock climber named Adam Grosowsky from southern Illinois in 1976. A then sixteen-year-old Adam, the son of the head of Southern Illinois University's Design Department, became obsessed with a photo he found in the university library with the understated caption "Circus Performers c1890"; the photo depicted a wire bolted low on a wall on one end and the other terminating in a wristloop held by a performer doing a one-hand handstand on the top of a flagpole with his body canted far to the opposite side counterbalancing the weight of the wire. In the middle of that wire was another performer in a handstand. Adam successfully harassed the small band of local climbers into almost believing they could reproduce this feat. They all set about learning to walk on climbing ropes, webbing, chains and low / high wires, but only Adam managed to carry through with achieving some elements of that historic circus feat, most notably being able to maintain an indefinite handstand on 1-inch (2.5 cm) webbing and even getting it rocking side-to-side while in the handstand. Adam carried those bad habits to Olympia, Washington's The Evergreen State College in 1979,[11] where he met fellow climbers Jeff Ellington and Brooke Sandahl. Adam set up his permanent heavy highwire in the woods on campus while the trio continued to perfect walking, handstands, and jump mounts on webbing. Their handstand work focused on 1-inch (2.5 cm) flat climbing webbing and they also employed the dynamics and flexibility of the nylon webbing to develop all manner of other tricks, including a three-club passing (juggling) routine between two slackliners balanced simultaneously on the same line. Red Square, Evergreen's central campus plaza, was a convenient between-class practice area where they often drew crowds of spectators. Grosowsky, along with Ellington were fascinated with wirewalking history and circus culture from the start, and in 1981 performed leashless on a 30-foot (9 m) highline strung 25 feet (8 m) over a concrete floor as part of a project to recreate a traditional one-ring circus in The Evergreen State College's main performance auditorium. During this period Grosowsky, who is now a regionally well-known Northwest artist, devoted much of his lithographic art to themes involving wirewalking and circus culture. The sport blossomed within the West Coast rock climbing community, and then spread to other areas. It got attention during the 2016 Rio Olympics when slackliner Giovanna Petrucci performed on the beach at Ipanema, attracting the attention of the New York Times.[12]

Highlining history

Highlining was inspired by a number of highwire artists who walked steel cable up high in unique places. From 1907-1948, Mr. Ivy Baldwind of Eldorado Springs, Colorado crossed Eldorado Canyon on a high wire numerous times. His final crossing was documented on his 82nd birthday.[13] On August 7, 1974 Philippe Petit set-up and crossed a high wire between the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center in New York.[14] In the summer of 1983, Adam Grosowsky and Jeff Ellington set up a 55-foot (17 m) high wire at Yosemite's Lost Arrow Spire that was nearly 2,890 feet (880 m) high. However, neither of them were able to completely cross this line due to inadequate guying. In the autumn of 1983, inspired by Jeff and Adam's efforts, a 20-year-old Scott Balcom and 17-year-old Chris Carpenter successfully completed what is believed to be the first documented high walk on nylon webbing,[11][15] instead of using cable, giving birth to what slackliners now call highlining. This first highline, referred to as The Arches,[16] was a span about 30 feet (9 m) long and about 120 feet (35 m) above ground in Pasadena, California under the California SR 134 Freeway bridge, between two arches that spanned the trickling Arroyo Seco below. The next summer (1984), Scott Balcom set up a highline on Yosemite’s Lost Arrow Spire with the help of Darrin Carter and Chris Carpenter. Scott’s attempt, however, was unsuccessful (neither Darrin nor Chris made an attempt). On July 13, 1985, Scott Balcom returned and successfully crossed the now-famous Lost Arrow Spire highline.[17] In June 1990, Chris Carpenter purposefully "surfed" a highline spanning the gap of Horsetooth Rock in Fort Collins, Colorado. In 1993, Darrin Carter became the second person to successfully cross the Lost Arrow Spire highline.[14][18] In 1995, Darrin Carter performed unprotected crossings of the Lost Arrow Spire in Yosemite and The Fins, in Tucson, AZ on Mt. Lemmon highway.[11] On July 16, 2007, Libby Sauter became the first woman to successfully cross the Lost Arrow Spire,[19] with Jenna McLennan walking it shortly after.[20] In 2008, Dean Potter became the first person to BASE jump from a highline at Hell Roaring Canyon in Utah.[21] On September 10, 2011, Chris Rigby and Balance Community: Slackline Outfitters owner Jerry Miszewski established the Balance Community Highline Festival in Garden Valley, California. There has been a highline fest each month since; nine highlines are set up, ranging 35 to 400 feet (10 to 120 m) long for highliners from across the U.S. to come train on.[22][23][24]

Competitive sport history

Since 2010, the World Slackline Federation has tried to establish tricklining as a competitive sport. Jumps and other tricks are judged according to five criteria: difficulty, technique, diversity, amplitude (of jumps) and performance. Competitions are held on several levels.[25]

Tricklining history

Andy Lewis is known for having the longest history in competitive slacklining. He is considered to be the father of modern-day tricklining and has been the Overall World Champion of Competitive Tricklining since 2008. To date, he holds more prestigious international competition titles than anyone. In 2012, he performed a series of tricks during Madonna's Super Bowl XLVI Halftime Show, to a worldwide audience of 114 million people.[26]

World records

Longest highline

In Aiglun, France, on Tuesday, April 19, 2016 Nathan Paulin, along with Danny Menšík, set a new record for the longest slackline ever – 1020m. [27] The highline was 600 meters high at its highest point.

The longest highline walked by a woman, with a length of 222m at 400m high was set in Hunlen Falls, in Northern British Columbia on 24th August 2016 by Mia Noblet. [28]

Longest free solo highline

The longest free solo highline was walked in Hunlen Falls, in Northern British Columbia August, 2016. At a length of 72m and 400m high, it was walked by Friedi Kühne. [29]The longest free solo highline by a female is held by Faith Dickey, who walked a 28-meter-long highline in Ostrov, Czech Republic in August 2012. The line was 25 meters high.

Highest slackline

The highest slackline on record was walked by Christian Schou on August 3, 2006 at Kjerag in Rogaland, Norway. The slackline was 1,000 metres (3,281 ft) high. The project was repeated by Aleksander Mork in September 2007.

The current record for walking the highest urban highline is held by professional slackliner Reinhard Kleinlich of Austria, who walked a high wire at a height of 607 feet (185 m) on May 25, 2013 in front of the Messeturm Fair Tower in Frankfurt, Germany. "Reinhard Kleinlich, 32, used only his arms to balance as he walked twice along a 98-foot-long (30 m) polyester rope anchored to the two wings of Frankfurt's U-shaped skyscraper Tower 185 above hundreds of cheering supporters."[7][30][31]

Longest slackline (longline)

The longest slackline, with a length of 610 metres (2,000 ft), was walked on May 9, 2015 by Alexander Schulz in Mongolia.[32]

The longest slackline walked by a woman, with a length of 230 metres (750 ft), was walked in September 2014 in Lausanne (CH) by Laetitia Gonnon.

See also

References

- ↑ "What is Slacklining?". PTEN. 2013.

- ↑ "Primitive Slackline Setup". YouTube. 23 September 2015.

- ↑ "How to Set Up a Slackline". YouTube. 3 October 2006.

- ↑ "How to Build a Slackline". Wikihow.

- ↑ "How To Walk a Slackline". Wikihow.

- ↑ "How to Slackline: Jump Line-to-Line". Wikihow.

- 1 2 "US slackline walker Dean Potter crosses China canyon". BBC News. 23 April 2012.

- ↑ Alter, Alexandra (5 April 2008). "Into the Wild With Yoga". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 8 November 2012.

Jason Magness meditates in full-lotus posture balanced on a slackline over the Arizona desert.. He's also the innovator of slackline yoga and is one of its few masters.

- ↑ Bolster, Mary. "A climbing yogi has found a unique way to improve his balance, focus, and core strength: Doing yoga poses on a slackline". Yoga Journal. Retrieved 8 November 2012.

- ↑ Nadlonek, Ryan. "Highballin' – The Spot Gym Goes Off for Highball Comp". Climbing.com. Retrieved 8 November 2012.

they ran a slackline 20-feet in the air and tied in some of the area's most balanced men and women for toproped highline highjinx... The high-line event, which took place January 24, 2009, was a best-trick competition, with each slacker receiving three minutes to show their skills. Highlights included Greg Kalfa's ballsy backflip attempt and Josh Beau, looking as at home on the webbing as anyone else did on the ground (especially during his side-plank and other yoga-inspired moves).

- 1 2 3 Alpinist, Issue 21, Autumn 2007, "The Space Between, a history of funambulism" by Dean Potter

- ↑ ANNA JEAN KAISER (August 18, 2016). "This Rio Phenom Would Be a Lock for a Gold. If There Were One for Slacklining.". New York Times. Retrieved August 18, 2016.

..Petrucci is a world-champion slackliner, ... front flips and back flips and falls flat on the five-centimeter-wide strap, her torso parallel to the ground. ...If slackline were an Olympic sport, Petrucci, 18, would be a lock for gold....

- ↑ Rudolph M. Olson and the Carnegie Branch of the Boulder Public Library. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oJLBvBIoJ88

- 1 2 "The History of Slacklining".

- ↑ Walk the Line — the art of balance and the craft of slackline, by Scott Balcom 2005 ISBN 0-9764850-0-1

- ↑ "The Arches – 1983". rockclimbing.com.

- ↑ "First Slackline Crossing of the Lost Arrow Spire". YouTube. 24 May 2009.

- ↑ "History of Slacklining". slackline.com.

- ↑ YouTube: First Woman Walks the Lost Arrow Spire Highline

- ↑ "First Woman to Walk the Lost Arrow Spire". slackline.com. 2008.

- ↑ Longman, Jeré (14 March 2008). "900 Feet Up With Nowhere To Go But Down". The New York Times.

- ↑ "Slacklining". CBS Local. (video)

- ↑ Rigby, Chris; Miszewski, Jerry (9 September 2011). "Balance Community's Backyard Highline Fest". Facebook.

- ↑ "Balance Community Backyard Highline Festival: Volume VI". Facebook. 13 April 2012.

- ↑ "Rule Book" (PDF). World Slackline Federation. July 2012.

- ↑ "Who Was That Guy in the Toga With Madonna? And What Was He Doing?". Slate (magazine).

- ↑ redbull.com http://www.redbull.com/en/adventure/stories/1331789988303/these-guys-just-crossed-a-1020m-slackline. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ "MEET MIA - THE NEW FEMALE WORLD RECORD HOLDER [VIDEO]!". Retrieved 2016-09-27.

- ↑ Leftcoast (2016-09-01), New Free Solo Highline World Record by Friedi Kühne | shot in 4k, retrieved 2016-09-27

- ↑ Sheahan, Maria (26 May 2013). "Man Walks On High Rope Despite Fear Of Heights". Reuters.

- ↑ "Climber crosses canyon on slackline". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 24 April 2012. Retrieved 25 April 2012.

- ↑ Fullerton, Jamie (2015-05-14). "Daredevil breaks world slackline record with 610m walk in Mongolian desert". Daily Mail.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Slacklining. |

- International Slackline Association

- Slackline U.S. - Non-profit member based association

- Swiss Slackline

- Slackline Verband - Austrian association

- World listing of slackline festivals

- World listing of slackline achievements around you

- Slack People

- Slackline meetups

- Slackline Tricks Encyclopedia

- SlackMap

- Slackline history

- What is slackline? (in Greek)

- Slackline Australia- Peak Body for Slacklining in Australia

- Nathan Paulin