Solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance

Solid-state NMR (SSNMR) spectroscopy is a kind of nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, characterized by the presence of anisotropic (directionally dependent) interactions.

Introduction

Basic concepts

A spin interacts with a magnetic or an electric field. Spatial proximity and/or a chemical bond between two atoms can give rise to interactions between nuclei. In general, these interactions are orientation dependent. In media with no or little mobility (e.g. crystals, powders, large membrane vesicles, molecular aggregates), anisotropic interactions have a substantial influence on the behaviour of a system of nuclear spins. In contrast, in a classical liquid-state NMR experiment, Brownian motion leads to an averaging of anisotropic interactions. In such cases, these interactions can be neglected on the time-scale of the NMR experiment.

Examples of anisotropic nuclear interactions

Two directionally dependent interactions commonly found in solid-state NMR are the chemical shift anisotropy (CSA) and the internuclear dipolar coupling. Many more such interactions exist, such as the anisotropic J-coupling in NMR, or in related fields, such as the g-tensor in electron spin resonance. In mathematical terms, all these interactions can be described using the same formalism.

Experimental background

Anisotropic interactions modify the nuclear spin energy levels (and hence the resonance frequency) of all sites in a molecule, and often contribute to a line-broadening effect in NMR spectra. However, there is a range of situations when their presence can either not be avoided, or is even particularly desired, as they encode structural parameters, such as orientation information, on the molecule of interest.

High-resolution conditions in solids (in a wider sense) can be established using magic angle spinning (MAS), macroscopic sample orientation, combinations of both of these techniques, enhancement of mobility by highly viscous sample conditions, and a variety of radio frequency (RF) irradiation patterns. While the latter allows decoupling of interactions in spin space, the others facilitate averaging of interactions in real space. In addition, line-broadening effects from microscopic inhomogeneities can be reduced by appropriate methods of sample preparation.

Under decoupling conditions, isotropic interactions can report on the local structure, e.g. by the isotropic chemical shift. In addition, decoupled interactions can be selectively re-introduced ("recoupling"), and used, for example, for controlled de-phasing or transfer of polarization to derive a number of structural parameters.

Solid-state NMR line widths

The residual line width (full width at half max) of 13C nuclei under MAS conditions at 5–15 kHz spinning rate is typically in the order of 0.5–2 ppm, and may be comparable to solution-state NMR conditions. Even at MAS rates of 20 kHz and above, however, non linear groups (not a straight line) of the same nuclei linked via the homonuclear dipolar interactions can only be suppressed partially, leading to line widths of 0.5 ppm and above, which is considerably more than in optimal solution state NMR conditions. Other interactions such as the quadrupolar interaction can lead to line widths of thousands of ppm due to the strength of the interaction. The first-order quadrupolar broadening is largely suppressed by sufficiently fast MAS, but the second-order quadrupolar broadening has a different angular dependence and cannot be removed by spinning at one angle alone. Ways to achieve isotropic lineshapes for quadrupolar nuclei include spinning at two angles simultaneously (DOR), sequentially (DAS), or through refocusing the second-order quadrupolar interaction with a two-dimensional experiment such as MQMAS or STMAS.

Anisotropic interactions in solution-state NMR

From the perspective of solution-state NMR, it can be desirable to reduce motional averaging of dipolar interactions by alignment media. The order of magnitude of these residual dipolar couplings (RDCs) are typically of only a few rad/Hz, but do not destroy high-resolution conditions, and provide a pool of information, in particular on the orientation of molecular domains with respect to each other.

Dipolar truncation

The dipolar coupling between two nuclei is inversely proportional to the cube of their distance. This has the effect that the polarization transfer mediated by the dipolar interaction is cut off in the presence of a third nucleus (all of the same kind, e.g. 13C) close to one of these nuclei. This effect is commonly referred to as dipolar truncation. It has been one of the major obstacles in efficient extraction of internuclear distances, which are crucial in the structural analysis of biomolecular structure. By means of labeling schemes or pulse sequences, however, it has become possible to circumvent this problem in a number of ways.

Nuclear spin interactions in the solid phase

Chemical shielding

The chemical shielding is a local property of each nucleus, and depends on the external magnetic field.

Specifically, the external magnetic field induces currents of the electrons in molecular orbitals. These induced currents create local magnetic fields that often vary across the entire molecular framework such that nuclei in distinct molecular environments usually experience unique local fields from this effect.

Under sufficiently fast magic angle spinning, or in solution-state NMR, the directionally dependent character of the chemical shielding is removed, leaving the isotropic chemical shift.

J-coupling

The J-coupling or indirect nuclear spin-spin coupling (sometimes also called "scalar" coupling despite the fact that J is a tensor quantity) describes the interaction of nuclear spins through chemical bonds.

Dipolar coupling

Main article: Dipolar coupling (NMR)

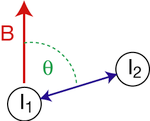

Nuclear spins exhibit a dipole moment, which interacts with the dipole moment of other nuclei (dipolar coupling). The magnitude of the interaction is dependent on the spin species, the internuclear distance, and the orientation of the vector connecting the two nuclear spins with respect to the external magnetic field B (see figure). The maximum dipolar coupling is given by the dipolar coupling constant d,

- ,

where r is the distance between the nuclei, and γ1 and γ2 are the gyromagnetic ratios of the nuclei. In a strong magnetic field, the dipolar coupling depends on the orientation of the internuclear vector with the external magnetic field by

- .

Consequently, two nuclei with a dipolar coupling vector at an angle of θm=54.7° to a strong external magnetic field, which is the angle where D becomes zero, have zero dipolar coupling. θm is called the magic angle. One technique for removing dipolar couplings, at least to some extent, is magic angle spinning.

Quadrupolar interaction

Nuclei with a spin greater than one-half have a non spherical charge distribution. This is known as a quadrupolar nucleus. A non spherical charge distribution can interact with an electric field gradient caused by some form of non-symmetry (e.g. in a trigonal bonding atom there are electrons around it in a plane, but not above or below it) to produce a change in the energy level in addition to the Zeeman effect. The quadrupolar interaction is the largest interaction in NMR apart from the Zeeman interaction and they can even become comparable in size. Due to the interaction being so large it can not be treated to just the first order, like most of the other interactions. This means you have a first and second order interaction, which can be treated separately. The first order interaction has an angular dependency with respect to the magnetic field of (the P2 Legendre polynomial), this means that if you spin the sample at (~54.74°) you can average out the first order interaction over one rotor period (all other interactions apart from Zeeman, Chemical shift, paramagnetic and J coupling also have this angular dependency). However, the second order interaction depends on the P4 Legendre polynomial, which has zero points at 30.6° and 70.1°. These can be taken advantage of by either using DOR (DOuble angle Rotation) where you spin at two angles at the same time, or DAS (Double Angle Spinning) where you switch quickly between the two angles. Specialized hardware (probe) has been developed for such experiments. A revolutionary advance is Lucio Frydman's multiple quantum magic angle spinning (MQMAS) NMR in 1995 and it has become a routine method for obtaining high resolution solid-state NMR spectra of quadrupolar nuclei.[2][3] A similar method to MQMAS is satellite transisition magic angle spinning (STMAS) NMR proposed by Zhehong Gan in 2000.

Other interactions

Paramagnetic substances are subject to the Knight shift.

History

See also: nuclear magnetic resonance or NMR spectroscopy articles for an account on discoveries in NMR and NMR spectroscopy in general.

History of discoveries of NMR phenomena, and the development of solid-state NMR spectroscopy:

Purcell, Torrey and Pound: "nuclear induction" on 1H in paraffin 1945, at about the same time Bloch et al. on 1H in water.

Modern solid-state NMR spectroscopy

Methods and techniques

Basic example

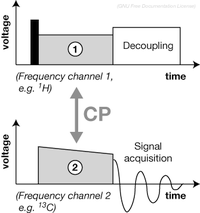

A fundamental RF pulse sequence and building-block in most solid-state NMR experiments starts with cross-polarization (CP) [Waugh et al.]. It can be used to enhance the signal of nuclei with a low gyromagnetic ratio (e.g. 13C, 15N) by magnetization transfer from nuclei with a high gyromagnetic ratio (e.g. 1H), or as spectral editing method (e.g. directed 15N→13C CP in protein spectroscopy). To establish magnetization transfer, the RF pulses applied on the two frequency channels must fulfill the Hartmann–Hahn condition [Hartmann, 1962], that is, the Lamor frequencies in both rf fields must be identical. Experimental optimization of such conditions is one of the routine tasks in performing a (solid-state) NMR experiment.

CP-MAS is a basic building block of most pulse sequences in solid-state NMR spectroscopy. Given its importance, a pulse sequence employing direct excitation of 1H spin polarization, followed by CP transfer to and signal detection of 13C, 15N) or similar nuclei, is itself often referred to as CP experiment, or, in conjunction with MAS, as CP-MAS [Schaefer and Stejskal, 1976]. It is the typical starting point of an investigation using solid-state NMR spectroscopy.

Decoupling

Spin interactions must be removed (decoupled) to increase the resolution of NMR spectra and isolate spin systems.

A technique that can substantially reduce or remove the chemical shift anisotropy, the dipolar coupling is sample rotation (most commonly magic angle spinning, but also off-magic angle spinning).

Homonuclear RF decoupling decouples spin interactions of nuclei that are the same as those being detected. Heteronuclear RF decoupling decouples spin interactions of other nuclei.

Recoupling

Although the broadened lines are often not desired, dipolar couplings between atoms in the crystal lattice can also provide very useful information. Dipolar coupling are distance dependent, and so they may be used to calculate interatomic distances in isotopically labeled molecules.

Because most dipolar interactions are removed by sample spinning, recoupling experiments are needed to re-introduce desired dipolar couplings so they can be measured.

An example of a recoupling experiment is the Rotational Echo DOuble Resonance (REDOR) experiment[4] which also can be the basis of an NMR crystallographic study of e.g. an amorphous solid.

Protons in solid-state NMR

In contrast to traditional approaches particular in protein NMR, in which the broad lines associated with protons effectively relegate this nucleus to mixing of magnetization, recent developments of hardware (very fast MAS) and reduction of dipolar interactions by deuteration have made protons as versatile as they are in solution NMR. This includes spectral dispersion in multi-dimensional experiments[5] as well as structurally valuable restraints and parameters important for studying the materials' dynamics.[6]

Applications

Biology

Membrane proteins and amyloid fibrils, the latter related to Alzheimer's disease and Parkinson's disease, are two examples of application where solid-state NMR spectroscopy complements solution-state NMR spectroscopy and beam diffraction methods (e.g. X-ray crystallography, electron microscopy). Solid-state NMR structure elucidation of proteins has traditionally been based on secondary chemical shifts and spatial contacts between heteronuclei. Currently, paramagnetic contact shifts[7] and specific proton-proton distances[8] are also used for higher resolution and longer-range distance restraints.

Chemistry

Solid-state NMR spectroscopy serves as an analysis tool in organic and inorganic chemistry. SSNMR is also a valuable tool to study local dynamics, kinetics, and thermodynamics of a variety of systems. Objects of SSNMR studies in materials science are inorganic/organic aggregates in crystalline and amorphous states, composite materials, heterogeneous systems including liquid or gas components, suspensions, and molecular aggregates with dimensions on the nanoscale, where different nuclei can be used as NMR probes. In many cases, NMR is the uniquely applicable method for measurement of porosity, particularly for porous systems containing partially filled pores or for dual-phase systems. Studies of solids by NMR relaxation experiments are special issues based on the following general statements. The experimental decay of macroscopic transverse or longitudinal magnetization follows the exponential law for complete domination of the spin-diffusion mechanism and a single relaxation time characterizes all of the nuclei in rigid solids, even those that are not chemically or structurally equivalent. The spin-diffusion mechanism is typical of systems with nuclei experiencing strong dipolar interactions (protons, fluorine or phosphorus nuclei at relatively small concentrations of paramagnetic centers). For other nuclei with weak dipolar coupling and/or at high concentration of paramagnetic centers, relaxation can be non-exponential following a stretched exponential function, exp(–(τ/T1)β) or exp(–(τ/T2)β). For paramagnetic solids, the β value of 0.5 corresponds to relaxation via direct electron–nucleus dipolar interactions without spin diffusion, while intermediate values between 0.5 and 1.0 can be attributed to a diffusion-limited mechanism.

Suggested readings: Bakhmutov, Vladimir. I. Solid-State NMR in Materials Science: Principles and Applications; CRC Press, 2012. Edition: 1st . ISBN 978-1439869635; ISBN 1439869634 Bakhmutov, Vladimir. I. NMR Spectroscopy in Liquids and Solids. CRC Press, 2015. Edition: 1st . ISBN 978-1482262704, ISBN 1482262703.

References

- ↑ "National Ultrahigh-Field NMR Facility for Solids". Retrieved 2014-09-22.

- ↑ Frydman Lucio; Hardwood John S (1995). "Isotropic Spectra of Half-Integer Quadrupolar Spins from Bidimensional Magic-Angle Spinning NMR". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 117: 5367–5368. doi:10.1021/ja00124a023.

- ↑ Massiot D.; Touzo B.; Trumeau D.; Coutures J. P.; Virlet J.; Florian P.; Grandinetti P. J. (1996). "Two-dimensional Magic-Angle Spinning Isotropic Reconstruction Sequences for Quadrupolar Nuclei". Solid-State NMR. 6: 73–83. doi:10.1016/0926-2040(95)01210-9.

- ↑ Gullion T.; Schaefer J. (1989). "Rotational-echo double-resonance NMR". J. Magn. Reson. 81: 196–200.

- ↑ Linser R.; Fink U.; Reif B. (2008). "Proton-Detected Scalar Coupling Based Assignment Strategies in MAS Solid-State NMR Spectroscopy Applied to Perdeuterated Proteins". J. Magn. Reson. 193: 89–93. Bibcode:2008JMagR.193...89L. doi:10.1016/j.jmr.2008.04.021.

- ↑ Schanda, P.; Meier, B. H.; Ernst, M. (2010). "Quantitative Analysis of Protein Backbone Dynamics in Microcrystalline Ubiquitin by Solid-State NMR Spectroscopy". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132: 15957–15967. doi:10.1021/ja100726a.

- ↑ Knight M. J.; Webber A. L.; Pell A. J.; Guerry P.; et al. (2011). "Fast Resonance Assignment and Fold Determination of Human Superoxide Dismutase by High-Resolution Proton-Detected Solid-State MAS NMR Spectroscopy". Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 50: 11697–11701. doi:10.1002/anie.201106340.

- ↑ Linser R.; Bardiaux B.; Higman V.; Fink U.; et al. (2011). "Structure Calculation from Unambiguous Long-Range Amide and Methyl 1H−1H Distance Restraints for a Microcrystalline Protein with MAS Solid-State NMR Spectroscopy". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133 (15): 5905–5912. doi:10.1021/ja110222h.

Suggested readings for beginners

- High Resolution Solid-State NMR of Quadrupolar Nuclei Grandinetti ENC Tutorial

- Laws David D., Hans- , Bitter Marcus L., Jerschow Alexej (2002). "Solid-State NMR Spectroscopic Methods in Chemistry". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 41: 3096–3129. doi:10.1002/1521-3773(20020902)41:17<3096::AID-ANIE3096>3.0.CO;2-X.

- Levitt, Malcolm H., Spin Dynamics: Basics of Nuclear Magnetic Resonance, Wiley, Chichester, United Kingdom, 2001. (NMR basics, including solids)

- Duer, Melinda J., Introduction to Solid-State NMR Spectroscopy, Blackwell, Oxford, 2004. (Some detailed examples of SSNMR spectroscopy)

Advanced readings

Books and major review articles

- McDermott, A, Structure and Dynamics of Membrane Proteins by Magic Angle Spinning Solid-State NMR Annual Review of Biophysics, v. 38, 2009.

- Mehring, M, Principles of High Resolution NMR in Solids, 2nd ed., Springer, Heidelberg, 1983.

- Slichter, C. P., Principles of Magnetic Resonance, 3rd ed., Springer, Heidelberg, 1990.

- Gerstein, B. C. and Dybowski, C., Transient Techniques in NMR of Solids, Academic Press, San Diego, 1985.

- Schmidt-Rohr, K. and Spiess, H.-W., Multidimensional Solid-State NMR and Polymers, Academic Press, San Diego, 1994.

- Dybowski, C. and Lichter, R. L., NMR Spectroscopy Techniques, Marcel Dekker, New York, 1987.

- Ramamoorthy, A., NMR Spectroscopy of Biological Solids, Taylor & Francis, New York, 2006.

General

References to books and research articles

- Andrew E. R.; Bradbury A.; Eades R. G. (1959). "Removal of Dipolar Broadening of Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectra of Solids by Specimen Rotation". Nature. 183: 1802–1803. Bibcode:1959Natur.183.1802A. doi:10.1038/1831802a0.

- Ernst, Bodenhausen, Wokaun: Principles of Nuclear Magnetic Resonance in One and Two Dimensions

- Hartmann S.R.; Hahn E.L. (1962). "Nuclear Double Resonance in the Rotating Frame". Phys. Rev. 128: 2042–2053. Bibcode:1962PhRv..128.2042H. doi:10.1103/physrev.128.2042.

- Pines A.; Gibby M.G.; Waugh J.S. (1973). "Proton-enhanced NMR of dilute spins in solids". J. Chem. Phys. 59: 569–90. Bibcode:1973JChPh..59..569P. doi:10.1063/1.1680061.

- Purcell, Torrey and Pound (1945).

- Schaefer J.; Stejskal E. O. (1976). "Carbon-13 Nuclear Magnetic Resonance of Polymers Spinning at the Magic Angle". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 98: 1031–1032. doi:10.1021/ja00420a036.

- Gullion T.; Schaefer J. (1989). "Rotational-Echo, Double-Resonance NMR". J. Magn. Reson. 81: 196.

- MacKenzie, K.J.D and Smith, M.E. "Multinuclear Solid-State NMR of Inorganic Materials", Pergamon Materials Series Volume 6, Elsevier, Oxford 2002.

External links

- SSNMRBLOG Solid-State NMR Literature Blog by Prof. Rob Schurko's Solid-State NMR group at the University of Windsor

- www.ssnmr.org Rocky Mountain Conference on Solid-State NMR

- http://mrsej.ksu.ru Magnetic Resonance in Solids. Electronic Journal