Southern grass skink

| Southern grass skink | |

|---|---|

.jpg) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Subphylum: | Vertebrata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Squamata |

| Suborder: | Sauria / Lacertilia |

| Infraorder: | Scincomorpha |

| Family: | Scincidae |

| Subfamily: | Eugongylinae[1] |

| Genus: | Pseudemoia |

| Species: | P. entrecasteauxii |

| Binomial name | |

| Pseudemoia entrecasteauxii (A.M.C. Duméril and Bibron, 1839) | |

| |

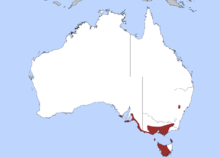

| Distribution of the southern grass skink | |

| Synonyms | |

The southern grass skink (Pseudemoia entrecasteauxii ) is a species of skink endemic to Australia, where it is found in the south-east of the continent, as well as in Tasmania and the islands of Bass Strait. Although it occurs in a variety of habitats, it is most commonly found in open grassy woodlands.[2][3]

Southern grass skinks have a lifespan of about 5 or 6 years. They grow up to 7.5 cm (3.0 in) in length (not including the tail). Male skinks change colouration during the breeding season.

Etymology

The specific name, entrecasteauxii, is in honor off French naval officer and explorer Antoine Bruni d'Entrecasteaux.[4]

Reproductive biology

The southern grass skink has become a model species for reproductive biology in reptiles because it gives birth to live young and exhibits non-invasive epitheliochorial placentation. Unlike other live bearing reptiles, Pseudemoia develop complex placentae, which provide a substantial amount of nutrients to the embryo through pregnancy.[5] The amount of nutrients provided is dependent on the amount of food females consume during pregnancy, and, unlike other live-bearing reptiles, scarcity of food during pregnancy can cause developmental failure. When food is limiting, females will also cannibalize their offspring. Together, these results suggest that placental nutrient transport may only be a successful mode of reproduction if food is abundant throughout pregnancy, which may limit its opportunities to evolve in some reptiles.[6] Lipid transport in this species most likely occurs through the yolk sac placenta and is facilitated in part by the production of the protein lipoprotein lipase.[7] The first observation of an extra-uterine pregnancy in a reptile was found in this species.[8] The extra-uterine embryo did not invade maternal tissue, suggesting fundamental differences between the nature and evolution of placentation in southern grass skinks and eutherian mammals.

References

- 1 2 "Pseudemoia entrecasteauxii ". The Reptile Database. www.reptile-database.org.

- ↑ DPIW: Native Plants and Animals – Southern Grass Skink

- ↑ Cogger HG. (1979). Reptiles and Amphibians of Australia. Sydney: Reed. ISBN 0-589-50108-9

- ↑ Beolens B, Watkins M, Grayson M. (2011). The Eponym Dictionary of Reptiles. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. xiii + 296 pp. ISBN 978-1-4214-0135-5. (Pseudemoia entrecasteauxii, p. 84).

- ↑ Thompson, MB; Stewart, JR; Speake, BK; Russell, KJ; McCartney, RJ; Surai, PF (1999). "Placental nutrition in a viviparous lizard (Pseudemoia pagenstecheri) with a complex placenta". Journal of Zoology. 248 (3): 295–305. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1999.tb01030.x.

- ↑ Van Dyke, JU; Griffith, OW; Thompson, MB (2014). "High food abundance permits the evolution of placentotrophy: evidence from a placental lizard, Pseudemoia entrecasteauxii". The American Naturalist. 184 (2): 198–210. doi:10.1086/677138.

- ↑ Griffith, OW; Ujvari, B; Belov, K; Thompson, MB (2013). "Placental lipoprotein lipase (LPL) gene expression in a placentotrophic lizard, Pseudemoia entrecasteauxii". Journal of Experimental Zoology Part B: Molecular and Developmental Evolution. 320 (7): 465–470. doi:10.1002/jez.b.22526.

- ↑ Griffith, OW; Van Dyke, JU; Thompson, MB (2013). "No implantation in an extra-uterine pregnancy of a placentotrophic reptile". Placenta. 34 (6): 510–511. doi:10.1016/j.placenta.2013.03.002.