Sports et divertissements

Sports et divertissements (Sports and Pastimes) is a cycle of 21 short piano pieces composed in 1914 by Erik Satie. The set consists of a prefatory chorale and 20 musical vignettes depicting various sports and leisure activities. First published in 1923, it has long been considered one of his finest achievements.[1][2][3]

Musically it represents the peak of Satie's humoristic piano suites (1912-1915), but stands apart from that series in its fusion of several different art forms. Sports originally appeared as a collector's album with illustrations by Charles Martin, accompanied by music, prose poetry and calligraphy. The latter three were provided by Satie in his exquisite handwritten scores, which were printed in facsimile.

Biographer Alan M. Gillmor wrote that "Sports et divertissements is sui generis, the one work in which the variegated strands of Satie's artistic experience are unselfconsciously woven into a single fragile tapestry of sight and sound — a precarious union of Satie the musician, the poet, and the calligrapher...At turns droll and amusing, serious and sardonic, this tiny Gesamtkunstwerk affords us as meaningful a glimpse of the composer's subconscious dreamworld as we are ever likely to get."[4]

Background

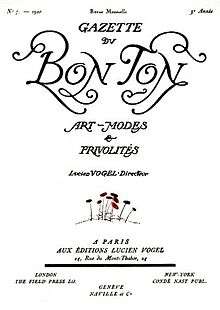

The idea for Sports et divertissements was initiated by Lucien Vogel (1886-1954), publisher of the influential Paris fashion magazine La Gazette du Bon Ton and later founder of the famous pictorial weekly Vu. It was conceived as a haute couture version of the livre d'artiste ("artist's book"), a sumptuous, expensive collector's album combining art, literature, and occasionally music, which was popular among French connoisseurs in the years before World War I.[5][6] Gazette illustrator Charles Martin provided the artwork, 20 witty copper plate etchings showing the affluent at play while dressed in the latest fashions. The title itself was an advertising slogan found in women's magazines of the period, designed to draw tourists to upscale resorts.[7]

An often repeated legend asserts that Igor Stravinsky - riding high from the scandalous success of his 1913 ballet Le Sacre du printemps - was first approached to compose the music, but rejected Vogel's proposed fee as too small. Gazette staffer Valentine Hugo then recommended Satie, with whom she had recently become friends. Although he was offered a lesser amount than Stravinsky, Satie claimed it was excessive and against his moral principles to accept; only when the fee was substantially reduced did he agree to the project.[8][9][10] According to independent Satie scholar Ornella Volta, a more probable resolution occurred when Satie's young disciple Alexis Roland-Manuel urged him to haggle for more money and was explosively scolded by the composer, who feared such demands would cause him to lose the commission altogether.[11] In fact the 3000 francs Satie received for Sports was by far the largest sum he had earned from his music up to that point.[12] Not two years earlier he had sold the first of his humoristic piano suites, the Véritables préludes flasques (pour un chien), for a mere 50 francs.[13]

Satie was familiar with the livre d'artiste tradition. Some of the earliest examples had been published by the Montmartre cabaret Le Chat Noir while he was a pianist there in the late 1880s.[14] He found in it an ideal format for his unique interdisciplinary talents. "Keep it short" was the only advice Satie ever gave aspiring young composers,[15] and the necessary restrictions of the Sports album - one page per composition - perfectly suited his predilection for brevity. Extramusical commentary was becoming increasingly prominent in his keyboard works of the period, and in Sports he indulged this by writing a surrealistic prose poem on each theme; he then meticulously calligraphed these into his India ink scores, in black ink for the notes and words and red ink for the staves. Whether Vogel expected these additional contributions or not, he wisely agreed to reproduce Satie's striking autographs in facsimile.

There is no record that Satie had contact with Charles Martin or access to his drawings while composing the suite.[16] Musicologists Robert Orledge and Steven Moore Whiting believe Satie directly musicalized at least one of the pictures, Le Golf (the last piece he composed);[17] otherwise, according to Whiting, "one finds a wide range of relationships between music-cum-story and drawing, from the close correspondence in Le Golf to outright contradiction, with varying degrees of reinterpretation in between."[18] If Satie knew of the images beforehand he evidently did not feel obligated to use them as the basis for his work, and filtered the different sporting themes through his own imagination instead. Thus, again from Whiting, "While the relation of Satie's music to his own texts is quite close, the relation of music to drawing is more elusive."[19]

Ultimately, Martin's 1914 etchings would not be seen by the public for many years. The long-delayed publication of Sports led the artist to replace them with an updated set of illustrations after World War I. As Satie's material remained unchanged, the new drawings are connected to the music and texts only by their titles.[20]

As noted on the individual scores, the pieces were completed from March 14 (La Pêche) to May 20 (Le Golf), 1914. Satie delivered them to Vogel in groups of three as the work progressed, drawing part of his fee (150 francs per piece) each time. The Préface and introductory chorale may have been tossed in gratis, as they were not part of the original project.[21] Satie would insist on installment payments for all his later big commissions. Conscious of his spendthrift nature when he had money, he used this method to cover his immediate living expenses and save himself from the temptation of squandering his entire fee at once, which had happened in the past.[22][23]

Music and texts

Satie's Préface for Sports describes the work as an amalgam of drawing and music, omitting any reference to his extramusical commentaries and calligraphy.[24] His prose poems are carefully threaded throughout the scores so that they may be read along with - but not easily spoken over - the piano part.[25]

Gillmor observed that "In several of the pieces Satie indulges in a kind of Augenmusik wherein the musical score is an obvious graphic representation of the activity being depicted."[26] In others the score is often closely linked to the text - such as in La Pêche - and the subtle details may not be perceived merely by listening. Performance of the music alone lasts between 13 and 15 minutes.

Préface

"This publication is made up of two artistic elements: drawing, music. The drawing part is represented by strokes – strokes of wit; the musical part is depicted by dots – black dots.[27] These two parts together – in a single volume – form a whole: an album. I advise the reader to leaf through the pages of this book with a kindly & smiling finger, for it is a work of fantasy. No more should be read into it.

For the Dried Up & Stultified I have written a Chorale which is serious & respectable. This Chorale is a sort of bitter preamble, a kind of austere & unfrivolous introduction. I have put into it everything I know about Boredom. I dedicate this Chorale to those who do not like me. I withdraw." - ERIK SATIE[28]

1. Choral inappetissant (Unappetizing Chorale) - Grave

Seriously. Surly & cantankerous. Hypocritically. More slowly. In the second half of his Préface Satie offered a rare "explanation" of one of his favorite musical jokes. He used the chorale form - that "symbol of Protestant piety and music pedagogy"[29] much employed by Bach - in several compositions to thumb his nose at the academic, the stupid and conformist. Satirical examples are found in his piano duet Aperçus désagréables (Unpleasant Glimpses) of 1908 and the orchestral suite En habit de cheval (1911) to his ballet Parade (in the revised 1919 version). The brief Choral inappetissant is built of sour, unsingable phrases that snub the whole purpose of the genre.[30] Here it serves to warn off the serious-minded from the light-hearted frivolity that ensues.

Beneath the date of the score (May 15, 1914) Satie noted, "In the morning, on an empty stomach."

2. La Balançoire (The Swing) - Lent

Slowly. Pendulum-like staccato quavers in the left hand underscore four poignant melodic phrases, including a quotation of L'escarpolette from Georges Bizet's 1871 piano suite Jeux d'enfants.[31] Satie's text for this piece is frequently cited as an exemplar of his haiku-like prose poems:

- It's my heart that is swinging like this. It isn't dizzy. What little feet it has.

- Will it be willing to return to my breast? [32]

3. La Chasse (Hunting) - Vif

Fast. Satie's first-person narrative is one of his most whimsical literary creations, an absurdist nature-setting in which rabbits sing, nightingales hide in burrows, and owls breast-feed their young. As for the hunter, he uses his rifle to shoot nuts out of the trees. This is presented in the typical "hunting rhythm" of 6/8, with bugle fifths in the treble and a concluding gunshot in the bass.[33]

4. La Comédie Italienne (The Italian Comedy) - A la napolitaine

In a Neapolitan manner. Scaramouche, a cowardly braggart from the Commedia dell'arte, tries to wax eloquent on the joys of military life. He is mocked with a courtly, ornamented tune that quickly goes awry with displaced accompaniments and ambiguous harmonies. Steven Moore Whiting wrote of this piece, "It is as if Satie had discovered in 1914 the same formula that Stravinsky would apply in Pulcinella six years later."[34]

5. Le Réveil de la Mariée (The Awakening of the Bride) - Vif, sans trop

Lively, but not too. In this boisterous aubade members of a wedding party arrive to rouse the newlywed bride from her marriage bed. The music quotes distorted bits of Frère Jacques ("Dormez-vous?") and the military bugle call Reveille. Somewhere in the tumult, Satie writes, "A dog is dancing with his fiancée."

6. Colin-Maillard (Blind Man's Buff) - Petitement

Pettily. Music and text weave a sentimental little drama. In a game of "Blind man's buff" a blindfolded lady approaches a man who has a crush on her. With "trembling lips" he yearns for her to tag him. She heedlessly passes him by, and the man's heartbreak is expressed in an unresolved chord.

7. La Pêche (Fishing) - Calme

Calmly. "The murmuring of the water in a riverbed" is suggested by a gentle repeating figure. A fish swims up, then another, then two more, accompanied by bitonal ascending flourishes. They casually observe a poor fisherman on the bank, then swim away. The fisherman goes home as well, leaving only "The murmuring of the water in a riverbed." Satie's construction of this piece - the first he composed in the set - is a perfectly symmetrical arch form (A B C B A).[35]

8. Le Yachting (Yachting) - Modéré

Moderately. (In half-notes, bass octaves). Legato. A stern ostinato in the lower reaches of the piano summons up a wind-blown sea as it tosses about members of a yachting party. A "pretty lady passenger" is not amused by the rough weather. "I'd rather do something else," she pouts. "Go fetch me a car." The sea ostinato returns to end the piece.

9. Le Bain de Mer (Sea Bathing) - Mouvementé

Eventfully. Another Satie seascape, with rushing arpeggios demonstrating that the ocean is not always congenial to casual tourists. A man leads a woman into the surf, cautioning her, "Don't sit at the bottom. It's very damp." Both are struck by some "good old waves", with the lady getting the worst of it. "You're all wet," the man observes. "Yes, sir," the woman replies.

10. Le Carnaval (Carnival) - Léger

Lightly. Confetti rains down on a Carnival celebration. Costumed revelers pose and jostle one another, including a drunken Pierrot who is behaving obnoxiously. "Are they pretty?" the text inquires. Satie answers with an ambivalent musical coda - similar to the ending of Colin-Maillard - and adds the playing direction "Hold back considerably."

11. Le Golf (Golf) - Exalté

Excitedly. In a sketch of a text related to Sports, Satie described golf as "a sport for mature men who have retired...Old English colonels especially excel at it."[36] Satie kept this idea as the basis for Le Golf, introducing a colonel dressed in "Scotch tweed of a violent green." He confidently strides through the links, intimidating even the holes in the ground and the clouds in the sky. His march-like theme remarkably prefigures Vincent Youmans' classic 1925 song Tea for Two.[37] The pompous colonel is deflated when his "fine swing" causes his club to shatter into pieces, described in the score by a sweep of ascending fourths.

12. La Pieuvre (The Octopus) - Assez vif

Briskly. A murky, dissonant piece. An octopus in its underwater cave teases a crab before swallowing it sideways. This gives the octopus severe indigestion. It drinks a glass of salt water and feels better.

13. Les Courses (Racing) - Un peu vif

Somewhat fast. Steadily galloping rhythms whip us through eight verbal snapshots of a horse race from start to finish. "The Losers" ("Les Perdants") dejectedly bring up the rear to a distorted rendition of the opening of La Marseillaise. Ornella Volta ventured that this parodic coda, written on the brink of World War I, "says a lot about Satie's military-patriotic sentiments."[38]

14. Les Quatre-Coins (Puss in the Corner) - Joie moderée

With moderate joy. In Satie's playfully literal idea of the children's game, four mice tease a cat, with predictable results. The implications of how "Puss" wins his "corner" are left to the listeners' imagination. The piece features another quote from Bizet's Jeux d'enfants on the same subject (Les quatre coins).[39]

15. Le Pique-nique (The Picnic) - Dansant

Dance-like. A pleasant outing - to which "Everyone has brought very cold veal" - gets rained out by a storm. The music opens with a folk-like dance that segues into a veiled illusion to Claude Debussy's cakewalk Le petit Nègre (1909).[40] After a recapitulation of the folk dance the piece ends abruptly with suggestions of thunder, which the picnickers initially mistake for the sound of an airplane.

16. Le Water-chute (The Water Chute) - Gracieusement

Graciously. To the strains of an innocuous waltz theme a pair of pleasure-seekers prepare to go on a water slide. The more reluctant of the two is persuaded with dubious reassurances ("You will feel as if you were falling off a scaffolding"). Following an expectant musical pause the ride itself is evoked with dizzying plunging scales. The squeamish one feels sick afterwards but is told, "That proves you needed to have some fun."[41]

17. Le Tango (perpétuel) (The [Perpetual] Tango) - Modéré & très ennuyé

Moderately & with great boredom. Satie's satirical view of the tango craze that swept Western Europe in the pre-World War I era. On January 10, 1914, Archbishop of Paris Léon-Adolphe Amette denounced the dance as immoral and forbade it to practicing Catholics.[42][43] Taking his cue from the cleric, Satie calls the tango "the Dance of the Devil" but then adds a droll glimpse of the Prince of Darkness's domestic life: "It's his favorite. He dances it to cool off. His wife, his daughters & his servants get cool that way."[44] The music is intentionally banal, an attenuated, vaguely "Spanish" tune wandering aimlessly through several keys over a persistent tango rhythm. As a final joke the repeat signs at the beginning and end of the score indicate the piece is to be played ad infinitum, presenting a hellish eternity of musical monotony.[45] Satie had earlier "suggested" 840 repetitions of his (then unpublished) 1893 piano piece Vexations, but in Le Tango he took this notion to its logical (and unperformable) conclusion.

18. Le Traîneau (The Sled) - Courez

Running. At under half a minute in performance the shortest piece in the set. Satie's music for the sled speeding along is purely descriptive - a series of skittering, frenetic bursts covering most of the keyboard - while the commentary is mostly concerned with the icy conditions: "Ladies, keep your noses inside your furs...The landscape is very cold and doesn't know what to do with itself."

19. Le Flirt (Flirting) - Agité

Agitatedly. An impetuous man tries to seduce an uninterested woman by telling her "nice things...modern things." She rebuffs him by saying "I would like to be on the moon", underscored by a snatch of the folksong Au clair de la lune.[46] The would-be lover nods his head in defeat.

20. Le Feu d'artifice (Fireworks) - Rapide

Rapidly. Another descriptive piece. As Bengal lights and other fireworks streak across the evening sky, "An old man goes crazy" among the spectators. Ascending triplets bring the number to an explosive climax, followed by a desolate whimper.[47]

21. Le Tennis (Tennis) - Avec cérémonie

Ceremoniously. In his June 1913 squib about Debussy's ballet Jeux for the journal Revue musicale S.I.M., Satie poked fun at Ballets Russes choreographer Vaslav Nijinsky for presenting it as a "tennis match" while taking absurd liberties with the game, which Nijinsky seemed to have confused with soccer (use of a football, no racquets or center court net). Satie mirthfully defined the result as a new sport, "Russian tennis", which he predicted would become "all the rage."[48][49] He may well have recalled this episode when he composed Le Tennis 10 months later. The music, while depicting the back-and-forth of the players, is strangely dark and ambiguous; and the implied eroticism that pervaded the choreography of Jeux is trivialized in Satie's text, in which the spectator-narrator mixes prosaic sensual observations ("What good-looking legs he has...what a fine nose") with correct sports terminology ("A slice serve!"). The piece, and the suite, end on one word (in English): "Game!"[50]

Publication

The complex early publication history of Sports et divertissements was elucidated by Ornella Volta in the 1980s.[51] It was apparently ready for the printers when World War I broke out in July 1914; under ensuing military censorship many French periodicals, including La Gazette du Bon Ton, folded or were suspended.[52] Vogel dissolved his company in 1916 and later sold the materials for Sports to the publisher Maynial. He remained interested in the project, however, and as Maynial made no effort to produce the album Vogel repurchased the rights under his new company Les Editions Lucien Vogel et du Bon Ton in March 1922. Fashions and graphic design had changed dramatically in the intervening years, so Charles Martin replaced his original illustrations with a new set of drawings in a Cubist-influenced style; these were rendered into full-color pochoir prints at the studio of Jean Saudé, a leading practitioner of the technique.[53] This edition was announced in January 1923, but the publisher Éditions de La Sirène, which then had Satie under exclusive contract, intervened to assert their rights over the music. The work's release was further delayed as Vogel worked out a settlement with La Sirène.[54]

A decade after its conception, Sports et divertissements was finally published in late 1923 in an edition of 900 numbered portfolio copies, on handmade paper. Facsimiles of Satie's scores (in black and red ink) appeared in all, but Martin's artwork was presented in three different print runs. The very rare first set, copies 1 to 10, included both Martin's original 1914 illustrations and his 1922 pochoir prints, his engraved Table of Contents and individual title pages, and cameos decorating the latter. These bibliophile volumes were not for sale but were reserved for the Librairie Maynial.[55] Copies 11 to 225 featured Martin's 1922 plates and title pages.[56] The third version (copies 226 to 900) had Martin's title pages and cameos but only one of his colorful illustrations (La Comédie Italienne) as a frontispiece.[57]

In 1926, Rouart, Lerolle & Cie purchased the rights for Sports from Vogel and brought out a standard performing edition, with Satie's facsimile scores in black ink only and without Martin's illustrations. It was republished by Salabert in 1964. In 1982, Dover Publications issued Satie's facsimiles together with black-and-white reproductions of Martin's 1922 illustrations as a trade paperback, and this is probably the best known English edition. It was reprinted in 2012.

The order of the pieces from the original edition onwards was chosen by Vogel and does not reflect Satie's preferences. The composer had a specific musical sequence in mind in 1914, which upon further reflection he changed for the 1922 public premiere.[58][59] While he eschewed standard compositional development and structure, Satie was highly aware of the formal "architecture" of his music and sequenced his multi-movement works with great care.[60] Robert Orledge, for one, believes that either of Satie's versions are musically preferable to the one selected by his publisher and ubiquitously performed ever since.[61]

For over 80 years most of Martin's 1914 illustrations were known only to a handful of private collectors and interested scholars. Ornella Volta published two (Le Water-chute and Le Pique-nique) in a 1987 article,[62] and Le Golf appeared in Robert Orledge's book Satie the Composer (1990).[63] An almost complete set (minus Le Traîneau) was presented in Volta's edition of Satie's literary writings, A Mammal's Notebook (1996), making the bulk of Martin's original work available for the first time.[64]

Reception

Initial response to Sports et divertissements was muted due to the limited nature of its original publication. When the first commercial performing edition appeared in 1926, Satie was dead and his growing reputation as a serious composer had been virtually destroyed by the widespread critical condemnation of his last work, the Dada ballet Relâche (1924).[65] While Satie's music faded from Parisian concert programs of the late 1920s and early 1930s,[66] Sports quietly circulated among musicians and faithful fans, some of whom immediately recognized its importance. Darius Milhaud called it "One of the most characteristic works of the modern French School,"[67] and biographer Pierre-Daniel Templier (1932) proclaimed that the spirits of Satie and of French music were "prodigiously alive" in its pages.[68] Some early enthusiasts looked to Japanese art to find antecedents to its miniaturist craft. Composer Charles Koechlin compared Sports to netsuke and pianist Alfred Cortot remarked on its haiku qualities.[69] In the English-speaking world the piece received its first significant boost after World War II from Rollo H. Myers' biography Erik Satie (1948), in which he ranked Sports with a handful of Satie compositions that are "outstanding and cannot be ignored by any student of contemporary music."[70] Myers continued, "Satie here proves himself an artist of the finest quality, working to a scale which in itself would be a handicap to most writers, let alone musicians, but triumphing over his self-imposed limitations with the virtuosity of a marksman scoring a bull's-eye with each shot. On a miniature range, perhaps; but is artistry a matter of dimensions?"[71]

Performance

In his Préface to Sports et divertissements, Satie wrote only of its conception as a printed album and offered no suggestions as to how it might be presented in a concert setting. It is worth noting that in his next composition, the piano suite Heures séculaires et instantanées (written June – July 1914), he issued his famous "warning" to the players forbidding them from reading his extramusical texts aloud during the performance.[72] His disciple Francis Poulenc confirmed this applied to all his mentor's humoristic piano music.[73] However Satie was not averse to the music for Sports being played and there were at least three performances before the completed album finally saw print.

On December 14, 1919, Lucien Vogel and his wife held a private musical soirée at their Paris apartment which included "a few little novelties, entitled Sports & Divertissements, by M. Erik Satie."[74] Details of this performance are lacking though it appears Satie himself was the pianist.[75] The public premiere was given by Satie's trusted interpreter of the 1920s, pianist Marcelle Meyer, at the Salle de La Ville l'Évêque in Paris on January 31, 1922. It was part of a three-concert series in which Meyer presented Satie's music in historical contexts, from the early clavecin masters to the contemporary avant-garde; Sports was programmed with piano pieces by members of Les Six.[76] This was followed by the US premiere in New York City on February 4, 1923, sponsored by Satie champion Edgard Varèse through the auspices of his International Composers Guild. George Gershwin was in the audience and saved a copy of the program.[77]

Patrick Gowers, writing for the New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians in 1980, described the multi-faceted yet intimate nature of Sports et divertissements as "a private art that tends to resist public performance."[78] Steven Moore Whiting elaborated on this, citing the eternally self-repeating Le Tango as proof of the impossibility of performing Sports as literally written. He argued: "The music can be played, but not the pictures or narratives. The 'work' is the composite of (or contrapuntal interplay between) verbal preface, musical preamble, drawings, illustrative piano pieces (which seldom agree completely with the illustrations), stories, performance instructions, calligraphy, and titles (some of them with variants)...How to do justice to all of this in a public recital?"[79]

There has nevertheless arisen a debatable performance tradition which presents Sports as a multi-media concert experience. Composer-critic Virgil Thomson, one of Satie's foremost American champions of the 20th Century, began performing Sports as a work for "narrator and piano" in New York City in the mid-1950s.[80] His translations of the texts appeared in the first English edition of Sports published by Salabert in 1975.[81] Thomson continued to perform it in this fashion to the end of his life. "I feel a connection with the Satie piece", he said in 1986, when he was 90. "It turns me on. You know there's a song that goes 'I don't know why I love you, but I do, ooooh, ooooh.'[82] Sometimes you know why you don't like something, but you don't know why you like it." [83]

Since then performances of Sports for voice and piano have been supplemented by arrangements for "speaker and ensemble," including chamber orchestra versions by composers Dominic Muldowney (1981) and David Bruce (2008).[84][85] A typical performance involves a narrator reading each of Satie's prose poems before the music is played; sometimes they are accompanied by background projections, either of Martin's illustrations, Satie's calligraphed scores, original artwork, or a combination of the three.[86] Orthodox Satie scholarship has largely ignored this trend, observing Satie's stated prohibition against the reading of his texts, and the majority of commercial recordings of Sports feature his music only. Pianist-musicologist Olof Höjer, who recorded Satie's complete piano music in the 1990s, found all the extramusical associations of Sports of secondary importance, claiming it is "Satie's music first and foremost that has made it a lasting work of art. What one loses in merely listening is marginal - such is the expressivity and precision of Satie's musical formulation."[87] And Whiting wondered if Sports et divertissements was best left to "a multi-media of the mind."[88]

Recordings

Notable recordings include those by Jean-Joël Barbier (BAM, 1967), Aldo Ciccolini (twice, for Angel in 1968 and EMI in 1987), Frank Glazer (Vox, 1968, reissued 1990), William Masselos (RCA, 1969, reissued 1995), John McCabe (Saga, 1974, reissued by Decca, 1986), Yūji Takahashi (Denon, 1979), France Clidat (Forlane, 1980), Jean-Pierre Armengaud - two versions: piano only (Le Chant Du Monde, 1986), and with Claude Piéplu narrating (Mandala, 1996), Anne Queffélec (Virgin Classics, 1988), Yitkin Seow (Hyperion, 1989), João Paulo Santos (Selcor, 1991, reissued 1999), Gabriel Tacchino (Disques Pierre Verany, 1993), Michel Legrand (Erato, 1993), Klára Körmendi (Naxos, 1994), Bojan Gorišek (Audiophile Classics, 1994), Jean-Marc Luisada with Jeanne Moreau as narrator (Deutsche Grammophon, 1994), Olof Höjer (Swedish Society Discofil, 1996), Pascal Rogé (Decca, 1997), Peter Dickinson (Olympia, 2001), Eve Egoyan (CBC, 2002), Jean-Yves Thibaudet (Decca, 2003), Håkon Austbø (Brilliant Classics, 2006), and Marielle Labèque (KML, 2009).

Notes and references

- ↑ Pierre-Daniel Templier, "Erik Satie", MIT Press, 1969, p. 85. Translated from the original French edition published by Rieder, Paris, 1932.

- ↑ Rollo H. Myers, "Erik Satie", Dover Publications, Inc., NY, 1968, p. 87. Originally published in 1948 by Denis Dobson Ltd., London.

- ↑ Patrick Gowers and Nigel Wilkins, "Erik Satie", "The New Grove: Twentieth-Century French Masters", Macmillan Publishers Limited, London, 1986, p. 140. Reprinted from the "The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians", 1980 edition.

- ↑ Alan M. Gillmor, "Musico-poetic Form in Satie's "Humoristic" Piano Suites (1913-14)", Canadian University Music Review/Revue de musique des universités canadiennes, n° 8, 1987, p. 37. See https://www.erudit.org/revue/cumr/1987/v/n8/1014932ar.pdf.

- ↑ Steven Moore Whiting, "Satie the Bohemian", Clarendon Press, 1999, p. 399.

- ↑ Mary E. Davis, "Erik Satie", Reaktion Books, 2007, pp. 94-96.

- ↑ Davis, "Erik Satie", p. 95.

- ↑ Myers, "Erik Satie", Dover Publications, Inc., NY, 1968, p. 87.

- ↑ Whiting, "Satie the Bohemian", p. 401, note 106.

- ↑ Olof Höjer's notes to "Erik Satie: The Complete Piano Music, Vol. 5", p. 23, Swedish Society Discofil, 1996.

- ↑ Whiting, "Satie the Bohemian", p. 401, note 106.

- ↑ Davis, "Erik Satie", p. 94.

- ↑ Templier, "Erik Satie", MIT Press, 1969, pp. 34-35.

- ↑ Whiting, "Satie the Bohemian", pp. 399-400.

- ↑ Ornella Volta (editor), "A Mammal's Notebook: The Writings of Erik Satie", Atlas Publishing, London, 1996 (reissued 2014), p. 11.

- ↑ Helen Julia Minors, "Exploring Interart Dialogue in Erik Satie's Sports et divertissements (1914/1922)", published as Chapter 6 in Dr. Caroline Potter (ed.), "Erik Satie: Music, Art and Literature", Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., 2013.

- ↑ Robert Orledge, "Satie the Composer", Cambridge University Press, 1990, p. 214.

- ↑ Whiting, "Satie the Bohemian", p. 403.

- ↑ Whiting, "Satie the Bohemian", p. 402.

- ↑ Orledge, "Satie the Composer", p. 303.

- ↑ Ornella Volta, "Give a Dog a Bone: Some investigations into Erik Satie." Originally published as "Le rideau se leve sur un os" in the Revue International de la Musique Francaise, Vol. 8, No. 23, 1987. English translation by Todd Niquette. Retrieved from Niclas Fogwall's defunct Satie Homepage (1996-2014) through the Internet Archive Wayback Machine at https://web.archive.org/web/20041014172728/http://www.af.lu.se/~fogwall/articl10.html#sports07r.

- ↑ Ornella Volta (ed.), "Satie Seen Through His Letters", Marion Boyars Publishers, London, 1989, pp. 75, 169-170.

- ↑ Satie evidently never kept a bank account. Author Blaise Cendrars recalled a 1924 experience helping the composer cash a large check in Paris and then trying to get him safely home with the money, while Satie insisted on stopping for meals, drinks, and to stock up on cigars and his favorite detachable collars (of which he bought a gross). Blaise Cendrars, interview on French Radio, July 3, 1950. Reprinted in Robert Orledge, "Satie Remembered", Faber and Faber Limited, 1995, pp. 132-134. Also see Henri Sauguet's reminiscences in the same book, p. 210.

- ↑ As Satie signed and dated the autograph scores for each number, the provenance of his calligraphy would not have been in question.

- ↑ Mary E. Davis, "Erik Satie", Reaktion Books, 2007, p. 96.

- ↑ Alan M. Gillmor, "Musico-poetic Form in Satie's "Humoristic" Piano Suites (1913-14)", pp. 33-35.

- ↑ A pun on the French term points noirs, meaning "blackheads".

- ↑ English summaries derived from the original French texts at IMSLP http://javanese.imslp.info/files/imglnks/usimg/3/35/IMSLP08174-Sports_et_divertissiments.pdf

- ↑ Mary E. Davis, "Erik Satie", Reaktion Books, 2007, p. 98.

- ↑ Rollo H. Myers nevertheless called the Choral inappetissant "an impressive fragment" and admired its "rugged strength and concentrated musical thinking." See Myers, "Erik Satie", p. 87.

- ↑ Mary E. Davis, "Classic Chic: Music, Fashion, and Modernism", University of California Press, 2006, pp. 87-89.

- ↑ Myers, "Erik Satie", p. 90.

- ↑ Höjer, notes to "Erik Satie: The Complete Piano Music, Vol. 5", p. 23.

- ↑ Whiting, "Satie the Bohemian", p. 405.

- ↑ Gillmor, "Musico-poetic Form in Satie's "Humoristic" Piano Suites (1913-14)", p. 34.

- ↑ Höjer, notes to "Erik Satie: The Complete Piano Music, Vol. 5", p. 23.

- ↑ Höjer, notes to "Erik Satie: The Complete Piano Music, Vol. 5", p. 23.

- ↑ Volta, "A Mammal's Notebook: The Writings of Erik Satie", p. 182, note 14.

- ↑ Davis, "Classic Chic: Music, Fashion, and Modernism", pp. 89-91.

- ↑ Robert Orledge, "Satie & Les Six". Published as Chapter 6 in Richard Langham Smith, Caroline Potter (editors), "French Music Since Berlioz", Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., 2006, pp. 223-248, info cited on pp. 227-228.

- ↑ Satie's use of a waltz theme and Martin's illustrations (both 1914 and 1922 versions) suggest the characters are an intimate couple, but Satie's text makes no reference to the gender of either.

- ↑ "Tango Dancing Must Be Confessed As Sin", The Cornell Daily Sun, Volume XXXIV, Number 82, 10 January 1914, http://cdsun.library.cornell.edu/cgi-bin/cornell?a=d&d=CDS19140110.2.41#

- ↑ Höjer, notes to "Erik Satie: The Complete Piano Music, Vol. 5", p. 23.

- ↑ The original French contains a pun: "se refroidissent ainsi" can also mean "catch cold that way."

- ↑ Whiting, "Satie the Bohemian", p. 407.

- ↑ Orledge, "Satie the Composer", p. 202.

- ↑ Gillmor, "Musico-poetic Form in Satie's "Humoristic" Piano Suites (1913-14)", p. 33.

- ↑ Orledge, "Satie the Composer", p. 64.

- ↑ Satie probably wrote this satirical "review" to amuse his longtime friend Debussy, who hated Nijinsky's choreography for Jeux. He offered no opinion of Debussy's score.

- ↑ Satie similarly opens the text of this piece with the English words "Play? Yes!"

- ↑ Volta, "Give a Dog a Bone: Some investigations into Erik Satie." See note 21.

- ↑ Apart from a special Summer issue in 1915, La Gazette du Bon Ton would not resume publication until January 1920. See Davis, "Classic Chic: Music, Fashion, and Modernism", p. 263, note 47.

- ↑ http://www.worldcat.org/title/sports-et-divertissements/oclc/221452424

- ↑ Volta, "Give a Dog a Bone". See note 21.

- ↑ Gavin Bryars, "Satie and the British", Contact 25 (1982), pp. 4-15.

- ↑ Trivia: The second copy of the original edition of Sports available to the public - No. 12 - was purchased by the eccentric English composer and Satie fan Lord Berners. See Bryars, "Satie and the British", pp. 4-15.

- ↑ To view the complete third version see http://satie-point.net/satie-sportsdiss-engl.html

- ↑ Satie's 1914 notebooks reveal he originally wanted the pieces played in this order: 1, 8, 18, 17, 10, 5, 11, 7, 12, 21, 15, 13, 9, 3, 2, 16, 6, 14, 4, 20, 19. The numbers refer to the sequence chosen by Vogel, published in subsequent editions and cited in this article. See Orledge, "Satie the Composer", p. 304.

- ↑ The sequence Marcelle Meyer played at the premiere was 1, 9, 16, 12, 6, 11, 19, 10, 21, 17, 5, 8, 18, 3, 13, 14, 15, 7, 20, 2, 4. See Orledge, "Satie the Composer", p. 304.

- ↑ Whiting, "Satie the Bohemian", p. 475.

- ↑ Orledge, "Satie the Composer", p. 304.

- ↑ Volta, "Give a Dog a Bone", cited above.

- ↑ Orledge, "Satie the Composer", p. 214.

- ↑ Volta, "A Mammal's Notebook: The Writings of Erik Satie", Atlas Publishing, London, 1996 (reissued 2014), pp. 29-45.

- ↑ Ann-Marie Hanlon, "Satie and the French Musical Canon: A Reception Study", University of Newcastle Upon Tyne, 2013, pp. 74-75, 103.

- ↑ Templier, "Erik Satie", p. 113.

- ↑ Myers, "Erik Satie", p. 85.

- ↑ Templier, "Erik Satie", p. 85.

- ↑ Myers, "Erik Satie", p. 85.

- ↑ Myers, "Erik Satie", p. 92.

- ↑ Myers, "Erik Satie", p. 90.

- ↑ Score of Heures séculaires et instantanées available at IMSLP.

- ↑ Francis Poulenc, "Erik Satie's Piano Music", La Revue Musicale, No. 214, June 1952, pp. 23-26. Reprinted in Nicolas Southon, "Francis Poulenc: Articles and Interviews: Notes from the Heart", Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., 2014.

- ↑ Volta, "Give a Dog a Bone", cited above.

- ↑ Höjer, notes to "Erik Satie: The Complete Piano Music, Vol. 5".

- ↑ http://www.musicalobservations.com/publications/satie.html. Paul Zukofsky, "Satie Notes", 2011, revised text of program notes for the 1991 Summergarden Concert Series of the Museum of Modern Art, New York City.

- ↑ Howard Pollack, "George Gershwin: His Life and Work", University of California Press, 2006, p. 37.

- ↑ Patrick Gowers and Nigel Wilkins, "Erik Satie", "The New Grove: Twentieth-Century French Masters", Macmillan Publishers Limited, London, 1986, p. 140. Reprinted from the "The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians", 1980 edition.

- ↑ Whiting, "Satie the Bohemian", pp. 407-408.

- ↑ "Colleagues Honor 90th Birthday of Virgil Thomson, Feisty Man of Music", New York Times, September 21, 1986, at http://www.nytimes.com/1986/09/21/arts/colleagues-honor-90th-birthday-of-virgil-thomson-feisty-man-of-music.html.

- ↑ http://www.worldcat.org/title/piano-music-vol-3-sports-divertisssments/oclc/658385356/editions?start_edition=11&sd=desc&referer=di&se=yr&editionsView=true&fq=

- ↑ A reference to Stevie Wonder's 1968 song "I Don't Know Why I Love You," covered by the Jackson 5 (who added the "ooooh, ooooh" to the lyrics) in 1970.

- ↑ "Colleagues Honor 90th Birthday of Virgil Thomson, Feisty Man of Music", New York Times, September 21, 1986.

- ↑ http://www.universaledition.com/Erik-Satie/composers-and-works/composer/629/work/4941

- ↑ http://www.worldcat.org/title/sports-et-divertissements-for-narrator-and-chamber-orchestra/oclc/704941175

- ↑ https://vimeo.com/69628543

- ↑ Höjer, notes to "Erik Satie: The Complete Piano Music, Vol. 5", p. 23.

- ↑ Whiting, "Satie the Bohemian", p. 408.