Ston

| Ston | |

|---|---|

|

Mali Ston | |

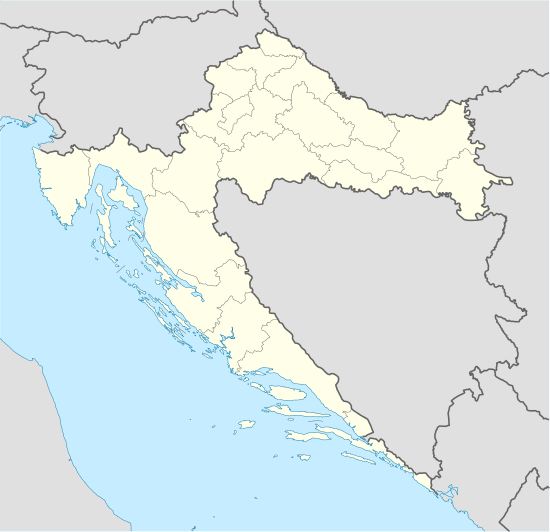

Ston The location of Konavle within Croatia | |

| Coordinates: 42°50′N 17°42′E / 42.833°N 17.700°ECoordinates: 42°50′N 17°42′E / 42.833°N 17.700°E | |

| Country | Croatia |

| County | Dubrovnik-Neretva county |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Vedran Antunica |

| Elevation | 0 m (0 ft) |

| Population (2011)[1] | |

| • Total | 2,407 |

| Time zone | CET (UTC+1) |

| • Summer (DST) | CEST (UTC+2) |

| Postal code | 20 230 |

| Area code(s) | +385 20 |

| Vehicle registration | DU |

| Website |

www |

Ston (pronounced [stɔ̂n]; Italian: Stagno) is a village and municipality in the Dubrovnik-Neretva County of Croatia, located at the south of isthmus of the Pelješac peninsula. The town of Ston is the center of the Ston municipality.

Municipality

In the 2011 census, the total population of the municipality of Ston was 2,407, in the following settlements:[1]

- Boljenovići, population 87

- Brijesta, population 58

- Broce, population 87

- Česvinica, population 55

- Dančanje, population 27

- Duba Stonska, population 36

- Dubrava, population 133

- Hodilje, population 190

- Luka, population 153

- Mali Ston, population 139

- Metohija, population 157

- Putniković, population 82

- Sparagovići, population 114

- Ston, population 549

- Tomislavovac, population 104

- Zabrđe, population 61

- Zamaslina, population 79

- Zaton Doli, population 61

- Žuljana, population 235

In the same census, Croats made up an absolute majority with 98.50% of the population.[2]

History

Stefan Vojislav (fl. 1018–43) held the Byzantine titles of archon, and toparch of the Dalmatian kastra of Zeta and Ston.[3] Mihailo I of Duklja (r. 1050–81), Vojislav's son, held Ston, where he had the St. Michael's Church built, which has his preserved ktitor portrait. Miroslav, the Grand Prince of Hum (r. 1166–90), was seated in the town. In 1219, Serbian Archbishop Sava established the Eparchy of Hum, which was seated in Ston.

On 22 January 1325, Stefan Uroš III issued a document for the sale of his maritime possessions of Ston and Pelješac to the Republic of Ragusa.[4][5] The Branivojević noble family held the areas under the Serbian crown, and were at the time the most powerful family in Hum. In 1326, they attacked Serbian interests and other local nobles of Hum, who in turn turned against Serbia and the Branivojevići. The Hum nobility approached Stjepan Kotromanić II, the ban of Bosnia, who then annexed most of Hum.[6] Ston and Pelješac were officially handed over to the Ragusans in 1333.[7]

Vukosav Nikolić was buried in Ston after his death in the Bosnian-Ragusan War (1403).[8]

Ston is also known for its saltworks which were run by the Republic of Ragusa and the Ottoman Empire.

Cultural monuments

Walls of Ston

Ston was a major fort of the Ragusan Republic whose defensive walls were regarded as a notable feat of medieval architecture.[9] The town's inner wall measures 890 metres in length, while the Great Wall outside the town has a circumference of 5 km. The walls extend to Mali Ston ("Little Ston"), a smaller town on the northern side of the Pelješac isthmus and the end of the Bay of Mali Ston, notable for its mariculture.

See also

Gallery

Saint Blaise Church in Ston, Croatia

Saint Blaise Church in Ston, Croatia Street in Ston, Croatia

Street in Ston, Croatia City Centre in Ston, Croatia

City Centre in Ston, Croatia Street in Ston, Croatia

Street in Ston, Croatia Street in Ston

Street in Ston Entrance to Ston City Walls in Croatia

Entrance to Ston City Walls in Croatia Anguis fragilis, or slow worm, in Ston, Croatia

Anguis fragilis, or slow worm, in Ston, Croatia

References

- 1 2 "Population by Age and Sex, by Settlements, 2011 Census: Ston". Census of Population, Households and Dwellings 2011. Zagreb: Croatian Bureau of Statistics. December 2012.

- ↑ "Population by Ethnicity, by Towns/Municipalities, 2011 Census: County of Dubrovnik-Neretva". Census of Population, Households and Dwellings 2011. Zagreb: Croatian Bureau of Statistics. December 2012.

- ↑ Paul Magdalino (January 2003). Byzantinum in the Year 1000. BRILL. pp. 124–. ISBN 90-04-12097-1.; Kekaumenos, ed Litavrin, 170-2

- ↑ Srpska akademija nauka i umetnosti 1908, p. 252

- ↑ Istorijski institut u Beogradu, SANU 1976, p. 21

- ↑ Fine, John Van Antwerp (1994), The Late Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century to the Ottoman Conquest, Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, p. 266, ISBN 978-0-472-08260-5

- ↑ Blagojević, Miloš (2001). Državna uprava u srpskim srednjovekovnim zemljama. Službeni list SRJ. p. 20.

Поуздано се зна да је приликом уступања Стона и Пељешца Дубровчанима 1333. године био присутан и казнац Балдовин.

- ↑ Marko Vego (1980). Iz istorije srednjovjekovne Bosne i Hercegovine. "Svjetlost," OOUR Izdavačka djelatnost. p. 318.

- ↑ Ston-www.croatia1.com

Sources

- Ćosić, Stjepan. “The Nobility of the Episcopal Town of Ston (Nobilitas civitatis episcopalis Stagnensis) Dubrovnik Annals, Vol. No. 5, 2001.

- Gudelj, Krešimira. “Coastal toponymy of the Ston region,” Folia onomastica Croatica, Vol. No. 20, 2011Melita Peharda, Mirjana Hrs-Brenko, Danijela Bogner, “Diversity of bivalve species in Mali Ston Bay, Adriatic Sea," Acta Adriatica, Vol. 45 No. 2, 2004.

- Lupis, Vinicije B. , “Mediaeval crucifixes from Ston and its surrounding area,” Starohrvatska prosvjeta, Vol. III No. 38, 2011.

- Miović, Vesna. "Emin (Customs Officer) as Representative of the Ottoman Empire in the Republic of Dubrovnik," Dubrovnik Annals 7 (2003): pp. 81–88.

- Tomšić, Sanja, and Josip Lovrić. “Historical overview of oyster culture in Mali Ston Bay,” Naše more, Znanstveno-stručni časopis za more i pomorstvo, Vol. 51 No. 1-2, 2004.

- Andrej Žmegač. “The Ston Fortification Complex - Several Issues,” Prilozi povijesti umjetnosti u Dalmaciji, Vol. 39 No. 1, 2005

- Nikodim, Bishop of Dalmatia and Istria (1914). Ston u srednjim vijekovima. Nakl. piščeva.

- Ratko Pasarić-Dubrovčanin (1983). Srpsko-pravoslavno žiteljstvo zapadnih krajeva Dubrovačke Republike do u 14. stoljeće: Ston, Stonski Rât, Primorje. Srpska pravoslavna eparhija zagrebačka.

- Mišić, Siniša (1997). Ston i Pelješac od 1326. do 1333. godine. Историјски часопис. 42-43. Istorijski institut. pp. 25–32. GGKEY:8N4K5PNPTJC.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ston. |