Step-growth polymerization

Step-growth polymerization refers to a type of polymerization mechanism in which bi-functional or multifunctional monomers react to form first dimers, then trimers, longer oligomers and eventually long chain polymers. Many naturally occurring and some synthetic polymers are produced by step-growth polymerization, e.g. polyesters, polyamides, polyurethanes, etc. Due to the nature of the polymerization mechanism, a high extent of reaction is required to achieve high molecular weight. The easiest way to visualize the mechanism of a step-growth polymerization is a group of people reaching out to hold their hands to form a human chain — each person has two hands (= reactive sites). There also is the possibility to have more than two reactive sites on a monomer: In this case branched polymers are produced.

Step growth polymerization and condensation polymerization

"Step growth polymerization" and condensation polymerization are two different concepts, not always identical. In fact polyurethane polymerizes with addition polymerization (because its polymerization produces no small molecules), but its reaction mechanism corresponds to a step-growth polymerization.

The distinction between "addition polymerization" and "condensation polymerization" was introduced by Wallace Hume Carothers in 1929, and refers to the type of products, respectively:[2][3]

- a polymer only (addition)

- a polymer and a molecule with a low molecular weight (condensation)

The distinction between "step-growth polymerization" and "chain-growth polymerization" was introduced by Paul Flory in 1953, and refers to the reaction mechanisms, respectively:[4]

- by functional groups (step-growth polymerization)

- by free-radical or ion (chain-growth polymerization)

Branched polymers

A monomer with functionality of 3 or more will introduce branching in a polymer and will ultimately form a cross-linked macrostructure or network even at low fractional conversion. The point at which a tree-like topology transits to a network is known as the gel point because it is signalled by an abrupt change in viscosity. One of the earliest so-called thermosets is known as bakelite. It is not always water that is released in step-growth polymerization: in acyclic diene metathesis or ADMET dienes polymerize with loss of ethylene.

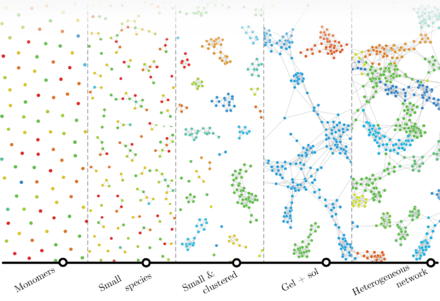

Polymers as complex networks

Polymers are macromolecules composed of many repeating units often arranged into complicated networks. In the liquid phase, in a melt or in solution, where each molecule constantly changes its shape as driven by the Brownian motion and advection fields, it is predominately the topology (i.e. the way monomers are arranged into a network) that determines the behaviour of the matter. In most of the cases topology has no regular patterns nor can topologies be observed directly, so one has to rely on models that are meant to predict the formation of a polymer network from scratch by mimicking the particular process of self-assembly or polymerisation. In this respect polymerization is a complex system that can be studied via the lens of complex-network formalism.[5] In this case formation of a molecular network from multifunctional precursors is represented by a random graph process. The process does not account for spatial positions of the monomers explicitly, yet the Euclidean distances between the monomers may derived from the topological information by applying self-avoiding random walks. This allows favoring reactivity of monomers that are close to each other, and to disfavour the reactivity for monomers obscured by the surrounding. The phenomena of conversion-dependent reaction rates, gelation, microgelation, and structural inhomogeneity are predicted by such a model. Moreover, many polymer properties can be extracted from graph theoretical description, these include such descriptors as size distribution, crosslink distances, and gel-point conversion.[5]

Differences between step-growth polymerization and chain-growth polymerization

This technique is usually compared with chain-growth polymerization to show its characteristics.

| Step-growth polymerization | Chain-growth polymerization |

|---|---|

| Growth throughout matrix | Growth by addition of monomer only at one end or both ends of chain |

| Rapid loss of monomer early in the reaction | Some monomer remains even at long reaction times |

| Similar steps repeated throughout reaction process | Different steps operate at different stages of mechanism (i.e. Initiation, propagation, termination, and chain transfer) |

| Average molecular weight increases slowly at low conversion and high extents of reaction are required to obtain high chain length | Molar mass of backbone chain increases rapidly at early stage and remains approximately the same throughout the polymerization |

| Ends remain active (no termination) | Chains not active after termination |

| No initiator necessary | Initiator required |

Historical Aspects

Most natural polymers being employed at early stage of human society are of condensation type. The synthesis of first truly synthetic polymeric material, Bakelite, was announced by Leo Baekeland in 1907, through a typical step-growth polymerization fashion of phenol and formaldehyde. The pioneer of synthetic polymer science, Wallace H. Carothers, developed a new means of making polyesters through step-growth polymerization in 1930s as a research group leader at DuPont. It was the first reaction designed and carried out with the specific purpose of creating high molecular weight polymer molecules, as well as the first polymerization reaction whose results had been predicted beforehand by scientific theory. Carothers developed a series of mathematic equations to describe the behavior of step-growth polymerization systems which are still known as the Carothers equations today. Collaborating with Paul J. Flory, who is a physical chemist, they developed theories that describe more mathematical aspects of step-growth polymerization including kinetics, stoichiometry, and molecular weight distribution etc. Carothers is also well known for his invention of Nylon.

Classes of step-growth polymers

Classes of step-growth polymers are:[6][7]

- Polyester has high glass transition temperature Tg and high melting point Tm, good mechanical properties to about 175 °C, good resistance to solvent and chemicals. It can exist as fibers and films. The former is used in garments, felts, tire cords, etc. The latter appears in magnetic recording tape and high grade films.

- Polyamide (nylon) has good balance of properties: high strength, good elasticity and abrasion resistance, good toughness, favorable solvent resistance. The applications of polyamide include: rope, belting, fiber cloths, thread, substitute for metal in bearings, jackets on electrical wire.

- Polyurethane can exist as elastomers with good abrasion resistance, hardness, good resistance to grease and good elasticity, as fibers with excellent rebound, as coatings with good resistance to solvent attack and abrasion and as foams with good strength, good rebound and high impact strength.

- Polyurea shows high Tg, fair resistance to greases, oils, and solvents. It can be used in truck bed liners, bridge coating, caulk and decorative designs.

- Polysiloxane are available in a wide range of physical states—from liquids to greases, waxes, resins, and rubbers. Uses of this material are as antifoam and release agents, gaskets, seals, cable and wire insulation, hot liquids and gas conduits, etc.

- Polycarbonates are transparent, self-extinguishing materials. They possess properties like crystalline thermoplasticity, high impact strength, good thermal and oxidative stability. They can be used in machinery, auto-industry, and medical applications. For example, the cockpit canopy of F-22 Raptor is made of high optical quality polycarbonate.

- Polysulfides have outstanding oil and solvent resistance, good gas impermeability, good resistance to aging and ozone. However, it smells bad, and it shows low tensile strength as well as poor heat resistance. It can be used in gasoline hoses, gaskets and places that require solvent resistance and gas resistance.

- Polyether shows good thermoplastic behavior, water solubility, generally good mechanical properties, moderate strength and stiffness. It is applied in sizing for cotton and synthetic fibers, stabilizers for adhesives, binders, and film formers in pharmaceuticals.

- Phenol formaldehyde resin (Bakelite) have good heat resistance, dimensional stability as well as good resistance to most solvents. It also shows good dielectric properties. This material is typically used in molding applications, electrical, radio, televisions and automotive parts where their good dielectric properties are of use. Some other uses include: impregnating paper, varnishes, decorative laminates for wall coverings.

- Poly-Triazole polymers are produced from monomers which bear both an alkyne and azide functional group. The monomer units are linked to each other by the a 1,2,3-triazole group; which is produced by the 1,3-Dipolar cycloaddition, also called the Azide-alkyne Huisgen cycloaddition. These polymers can take on the form of a strong resin,[8] or a gel.[9] With oligopeptide monomers containing a terminal alkyne and terminal azide the resulting clicked peptide polymer will be biodegradable due to action of endopeptidases on the oligopeptide unit.[10]

Kinetics

The kinetics and rates of step-growth polymerization can be described using a polyesterification mechanism. The simple esterification is an acid-catalyzed process in which protonation of the acid is followed by interaction with the alcohol to produce an ester and water. However, there are a few assumptions needed with this kinetic model. The first assumption is water (or any other condensation product) is efficiently removed. Secondly, the functional group reactivities are independent of chain length. Finally, it is assumed that each step only involves one alcohol and one acid.

This is a general rate law degree of polymerization for polyesterification where n= reaction order.

Self-catalyzed polyesterification

If no acid catalyst is added, the reaction will still proceed because the acid can act as its own catalyst. The rate of condensation at any time t can then be derived from the rate of disappearance of -COOH groups and

The second-order [\ce{COOH}] term arises from its use as a catalyst, and k is the rate constant. For a system with equivalent quantities of acid and glycol, the functional group concentration can be written simply as

After integration and substitution from Carothers equation, the final form is the following

For a self-catalyzed system, the number average degree of polymerization (Xn) grows proportionally with .[11]

External catalyzed polyesterification

The uncatalyzed reaction is rather slow, and a high Xn is not readily attained. In the presence of a catalyst, there is an acceleration of the rate, and the kinetic expression is altered to[1]

which is kinetically first order in each functional group. Hence,

and integration gives finally

For an externally catalyzed system, the number average degree of polymerization grows proportionally with .

Molecular weight distribution in linear polymerization

The product of a polymerization is a mixture of polymer molecules of different molecular weights. For theoretical and practical reasons it is of interest to discuss the distribution of molecular weights in a polymerization. The molecular weight distribution (MWD) had been derived by Flory by a statistical approach based on the concept of equal reactivity of functional groups.[12][13]

Probability

Step-growth polymerization is a random process so we can use statistics to calculate the probability of finding a chain with x-structural units ("x-mer") as a function of time or conversion.

Probability that an 'A' functional group has reacted

Probability of finding an 'A' unreacted

Combining the above two equations leads to.

Where Px is the probability of finding a chain that is x-units long and has an unreacted 'A'. As x increases the probability decreases.

Number fraction distribution

The number fraction distribution is the fraction of x-mers in any system and equals the probability of finding it in solution.

Where N is the total number of polymer molecules present in the reaction.[14]

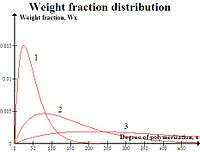

Weight fraction distribution

The weight fraction distribution is the fraction of x-mers in a system and the probability of finding them in terms of mass fraction.[1]

Notes:

- Mo is the molar mass of the repeat unit,

- No is the initial number of monomer molecules,

- and N is the number of unreacted functional groups

Substituting from the Carothers equation

We can now obtain:

PDI

The polydispersity index (PDI), is a measure of the distribution of molecular mass in a given polymer sample.

However for step-growth polymerization the Carothers equation can be used to substitute and rearrange this formula into the following.

Therefore, in step-growth when p=1, then the PDI=2.

Molecular weight control in linear polymerization

Need for stoichiometric control

There are two important aspects with regard to the control of molecular weight in polymerization. In the synthesis of polymers, one is usually interested in obtaining a product of very specific molecular weight, since the properties of the polymer will usually be highly dependent on molecular weight. Molecular weights higher or lower than the desired weight are equally undesirable. Since the degree of polymerization is a function of reaction time, the desired molecular weight can be obtained by quenching the reaction at the appropriate time. However, the polymer obtained in this manner is unstable in that it leads to changes in molecular weight because the ends of the polymer molecule contain functional groups that can react further with each other.

This situation is avoided by adjusting the concentrations of the two monomers so that they are slightly nonstoichiometric. One of the reactants is present in slight excess. The polymerization then proceeds to a point at which one reactant is completely used up and all the chain ends possess the same functional group of the group that is in excess. Further polymerization is not possible, and the polymer is stable to subsequent molecular weight changes.

Another method of achieving the desired molecular weight is by addition of a small amount of monofunctional monomer, a monomer with only one functional group. The monofunctional monomer, often referred to as a chain stopper, controls and limits the polymerization of bifunctional monomers because the growing polymer yields chain ends devoid of functional groups and therefore incapable of further reaction.[13]

Quantitative aspects

To properly control the polymer molecular weight, the stoichiometric imbalance of the bifunctional monomer or the monofunctional monomer must be precisely adjusted. If the nonstoichiometric imbalance is too large, the polymer molecular weight will be too low. It is important to understand the quantitative effect of the stoichiometric imbalance of reactants on the molecular weight. Also, this is necessary in order to know the quantitative effect of any reactive impurities that may be present in the reaction mixture either initially or that are formed by undesirable side reactions. Impurities with A or B functional groups may drastically lower the polymer molecular weight unless their presence is quantitatively taken into account.[13]

More usefully, a precisely controlled stoichiometric imbalance of the reactants in the mixture can provide the desired result. For example, an excess of diamine over an acid chloride would eventually produce a polyamide with two amine end groups incapable of further growth when the acid chloride was totally consumed. This can be expressed in an extension of the Carothers equation as,

were r is the ratio of the number of molecules of the reactants.

- were NBB is the molecule in excess.

The equation above can also be used for a monofunctional additive which is the following,

where NB is the number of monofunction molecules added. The coefficient of 2 in front of NB is require since one B molecule has the same quantitative effect as one excess B-B molecule.[15]

Multi-chain polymerization

A monomer with functionality 3 has 3 functional groups which participate in the polymerization. This will introduce branching in a polymer and may ultimately form a cross-linked macrostructure. The point at which this three-dimensional network is formed is known as the gel point, signaled by an abrupt change in viscosity.

A more general functionality factor fav is defined for multi-chain polymerization, as the average number of functional groups present per monomer unit. For a system containing N0 molecules initially and equivalent numbers of two function groups A and B, the total number of functional groups is N0fav.

And the modified Carothers equation is[16]

- , where p equals to

Advances in step-growth Polymers

The driving force in designing new polymers is the prospect of replacing other materials of construction, especially metals, by using lightweight and heat-resistant polymers. The advantages of lightweight polymers include: high strength, solvent and chemical resistance, contributing to a variety of potential uses, such as electrical and engine parts on automotive and aircraft components, coatings on cookware, coating and circuit boards for electronic and microelectronic devices, etc. Polymer chains based on aromatic rings are desirable due to high bond strengths and rigid polymer chains. High molecular weight and crosslinking are desirable for the same reason. Strong dipole-dipole, hydrogen bond interactions and crystallinity also improve heat resistance. To obtain desired mechanical strength, sufficiently high molecular weights are necessary, however, decreased solubility is a problem. One approach to solve this problem is to introduce of some flexibilizing linkages, such as isopropylidene, C=O, and SO

2 into the rigid polymer chain by using an appropriate monomer or comonomer. Another approach involves the synthesis of reactive telechelic oligomers containing functional end groups capable of reacting with each other, polymerization of the oligomer gives higher molecular weight, referred to as chain extension.[17]

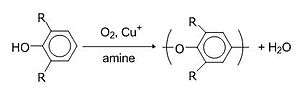

Aromatic polyether

The oxidative coupling polymerization of many 2,6-disubstituted phenols using a catalytic complex of a cuprous salt and amine form aromatic polyethers, commercially referred to as poly(p-phenylene oxide) or PPO. Neat PPO has little commercial uses due to its high melt viscosity. Its available products are blends of PPO with high-impact polystyrene (HIPS).

Polyethersulfone

Polyethersulfone (PES) is also referred to as polyetherketone, polysulfone. It is synthesized by nucleophilic aromatic substitution between aromatic dihalides and bisphenolate salts. Polyethersulfones are partially crystalline, highly resistant to a wide range of aqueous and organic environment. They are rated for continuous service at temperatures of 240-280 °C. The polyketones are finding applications in areas like automotive, aerospace, electrical-electronic cable insulation.

Aromatic polysulfides

Poly(p-phenylene sulfide) (PPS) is synthesized by the reaction of sodium sulfide with p-dichlorobenzene in a polar solvent such as 1-methyl-2-pyrrolidinone (NMP). It is inherently flame-resistant and stable toward organic and aqueous conditions; however, it is somewhat susceptible to oxidants. Applications of PPS include automotive, microwave oven component, coating for cookware when blend with fluorocarbon polymers and protective coatings for valves, pipes, electromotive cells, etc.[18]

Aromatic polyimide

Aromatic polyimides are synthesized by the reaction of dianhydrides with diamines, for example, pyromellitic anhydride with p-phenylenediamine. It can also be accomplished using diisocyanates in place of diamines. Solubility considerations sometimes suggest use of the half acid-half ester of the dianhydride, instead of the dianhydride itself. Polymerization is accomplished by a two-stage process due to the insolubility of polyimides. The first stage forms a soluble and fusible high-molecular-weight poly(amic acid) in a polar aprotic solvent such as NMP or N,N-dimethylacetamide. The poly(amic aicd) can then be processed into the desired physical form of the final plymer product (e.g., film, fiber, laminate, coating) which is insoluble and infusible.

Telechelic oligomer approach

Telechelic oligomer approach applies the usual polymerization manner except that one includes a monofunctional reactant to stop reaction at the oligomer stage, generally in the 50-3000 molecular weight. The monofunctional reactant not only limits polymerization but end-caps the oligomer with functional groups capable of subsequent reaction to achieve curing of the oligomer. Functional groups like alkyne, norbornene, maleimide, nitrite, and cyanate have been used for this purpose. Maleimide and norbornene end-capped oligomers can be cured by heating. Alkyne, nitrile, and cyanate end-capped oligomers can undergo cyclotrimerization yielding aromatic structures.

See also

External links

References

- 1 2 3 Cowie, J.M.G; Arrighi, V., Polymers: Chemistry and Physics of Modern Materials. 3 ed.; CRC Press: 2008.

- ↑ W. H. Carothers (1929). "STUDIES ON POLYMERIZATION AND RING FORMATION. I. AN INTRODUCTION TO THE GENERAL THEORY OF CONDENSATION POLYMERS". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 51 (8): 2548–2559. doi:10.1021/ja01383a041.

- ↑ Paul J. Flory, "Principles of Polymer Chemistry", Cornell University Press, 1953, p.39. ISBN 0-8014-0134-8

- ↑ Susan E. M. Selke, John D. Culter, Ruben J. Hernandez, "Plastics packaging: Properties, processing, applications, and regulations", Hanser, 2004, p.29. ISBN 1-56990-372-7

- 1 2 3 Kryven, I.; Duivenvoorden, J.; Hermans, J.; Iedema, P.D. (2016). "Random graph approach to multifunctional molecular networks.". Macromolecular Theory and Simulation. 25 (5): 449–465.

- ↑ Seymour, Raymond (1992). Polymer Chemistry An Introduction. Marcel Dekker, Inc. ISBN 0-8247-8719-6.

- ↑ H.F. Mark, N. M. B., C. G. Overberger, G. Menges, Encyclopedia of Polymer Science and Engineering Wiley-Interscience: New York, 1988.

- ↑ Wan, L.; Luo, Y.; Xue, L.; Tian, J.; Hu, Y.; Qi, H.; Shen, X.; Huang, F.; Du, L.; Chen, X. (2007). "Preparation and properties of a novel polytriazole resin. J. Appl. Polym". Sci. 104: 1038–1042. doi:10.1002/app.24849.

- ↑ Yujing, L.; Liqiang, W.; Hao, Z; Farong, H.; Lei, D. (2013). "A novel polytriazole-based organogel formed by the effects of copper ions". Polym. Chem. 4: 3444–3447. doi:10.1039/C3PY00227F.

- ↑ Van Dijk, M.; Nollet, M.; Weijers, P.; Dechesne, A.; van Nostrum, C.; Hennink, W.; Rijkers, D.; Liskamp, R. (2008). "Synthesis and Characterization of Biodegradable Peptide-Based Polymers Prepared by Microwave-Assisted Click Chemistry". Biomacromolecules. 10: 2834–2843. doi:10.1021/bm8005984.

- ↑ Yves Gnanou; Fontanille, M., Organic and Physical Chemistry of Polymers.

- ↑ Flory, Paul. Principles of Polymer Chemistry. Cornell University Press. pp. 321–322.

- 1 2 3 Odian, George (1991). Principles of polymerization. John Wiley& Sons, INC. ISBN 0-471-61020-8.

- ↑ Stockmayer, Waters (1952). "Molecular distribution in condensation polymers". Journal of polymer science. IX (1): 69–71. Bibcode:1952JPoSc...9...69S. doi:10.1002/pol.1952.120090106.

- ↑ Stevens, Malcolm (1990). Polymer Chemistry An Introduction. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195057597.

- ↑ Carothers, Wallace (1936). "Polymers and polyfunctionality". Transaction of the Faraday Society. 32: 39–49. doi:10.1039/TF9363200039.

- ↑ Rogers ME, Long TE, Turners SR. Synthetic methods in step-growth polymers. Wiley-Interscience.

- ↑ Walton, David; Phillip, Lorimer (2000). Polymers. Oxford Univ Pr on Demand. ISBN 0-19-850389-X.