Strongly correlated material

Strongly correlated materials are a wide class of heavy fermion compounds that include insulators and electronic materials, and show unusual (often technologically useful) electronic and magnetic properties, such as metal-insulator transitions, half-metallicity, and spin-charge separation, observed in the mineral Herbertsmithite that property is determined by quantum spin liquid or strongly correlated quantum spin liquid. The essential feature that defines these materials is that the behavior of their electrons or spinons cannot be described effectively in terms of non-interacting entities.[1] Theoretical models of the electronic (fermionic) structure of strongly correlated materials must include electronic (fermionic) correlation to be accurate.

Transition metal oxides

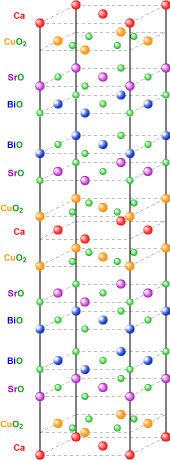

Many transition metal oxides belong into this class[2] which may be subdivided according to their behavior, e.g. high-Tc, spintronic materials, Mott insulators, spin Peierls materials, heavy fermion materials, quasi-low-dimensional materials, etc. The single most intensively studied effect is probably high-temperature superconductivity in doped cuprates, e.g. La2-xSrxCuO4. Other ordering or magnetic phenomena and temperature-induced phase transitions in many transition-metal oxides are also gathered under the term "strongly correlated materials."

Electronic structures

Typically, strongly correlated materials have incompletely filled d- or f-electron shells with narrow energy bands. One can no longer consider any electron in the material as being in a "sea" of the averaged motion of the others (also known as mean field theory). Each single electron has a complex influence on its neighbors.

The term strong correlation refers to behavior of electrons in solids that is not well-described (often not even in a qualitatively correct manner) by simple one-electron theories such as the local-density approximation (LDA) of density-functional theory or Hartree–Fock theory. For instance, the seemingly simple material NiO has a partially filled 3d-band (the Ni atom has 8 of 10 possible 3d-electrons) and therefore would be expected to be a good conductor. However, strong Coulomb repulsion (a correlation effect) between d-electrons makes NiO instead a wide-band gap insulator. Thus, strongly correlated materials have electronic structures that are neither simply free-electron-like nor completely ionic, but a mixture of both.

Theories

Extensions to the LDA (LDA+U, GGA, SIC, GW, etc.) as well as simplified models Hamiltonians (e.g. Hubbard-like models) have been proposed and developed in order to describe phenomena that are due to strong electron correlation. Among them, dynamical mean field theory successfully captures the main features of correlated materials. Schemes that use both LDA and DMFT explain many experimental results in the field of correlated electrons.

Structural studies

Experimentally, optical spectroscopy, high-energy electron spectroscopies, resonant photoemission, and more recently resonant inelastic (hard and soft) X-ray scattering (RIXS) and neutron spectroscopy have been used to study the electronic and magnetic structure of strongly correlated materials. Spectral signatures seen by these techniques that are not explained by one-electron density of states are often related to strong correlation effects. The experimentally obtained spectra can be compared to predictions of certain models or may be used to establish constraints to the parameter sets. One has for instance established a classification scheme of transition metal oxides within the so-called Zaanen–Sawatzky–Allen diagram.[3]

Applications

The manipulation and use of correlated phenomena has applications like Superconducting magnets and in magnetic storage (CMR) technologies. Furthermore, other phenomena like the MI transition in VO2 is explored as a means to make smart windows to reduce the heating/cooling need of a room.[4]

References

- ↑ The strong-correlations puzzle, J. Quintanilla and C. Hooley, Physics World, Vol. 22, No. 6 (June 2009), pp. 32-37.

- ↑ Millis, A. J. "Lecture notes on "Strongly Correlated" Transition Metal Oxides" (PDF). Columbia University. Retrieved 20 June 2012.

- ↑ J. Zaanen; G. A. Sawatzky; J. W. Allen (1985). "Band Gaps and Electronic Structure of Transition-Metal Compounds" (PDF). Physical Review Letters. 55: 418–421. Bibcode:1985PhRvL..55..418Z. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.55.418.

- ↑ J. M. Tomczak; S. Biermann (2009). "Optical properties of correlated materials – Or why intelligent windows may look dirty.". Physica Status Solidi (b). 246: 1996–2005. arXiv:0907.1575

. Bibcode:2009PSSBR.246.1996T. doi:10.1002/pssb.200945231.

. Bibcode:2009PSSBR.246.1996T. doi:10.1002/pssb.200945231.

Further reading

- Anisimov, Vladimir; Yuri Izyumov (2010). Electronic Structure of Strongly Correlated Materials. Springer. ISBN 3-642-04825-0.

- Patrik Fazekas (1999). Lecture Notes on Electron Correlation and Magnetism. World Scientific. ISBN 9810224745.

- de Groot, Frank; Akio Kotani (2008). Core Level Spectroscopy of Solids. CRC Press. ISBN 0-8493-9071-0.

- Yamada, Kosaku (2004). Electron Correlations in Metals. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-57232-0.

- Robert Z. Bachrach, ed. (1992). Synchrotron radiation research : advances in surface and interface science. Plenum Press. ISBN 0-306-43872-0.

- Pavarini, Eva; Koch Erik; Vollhardt, Dieter; Lichtenstein, Alexander; (eds.) (2011). The LDA+DMFT approach to strongly correlated materials. Forschungszentrum Jülich. ISBN 978-3-89336-734-4.

- Amusia, M.; Popov, K.; Shaginyan, V.; Stephanovich, V. (2014). Theory of Heavy-Fermion Compounds - Theory of Strongly Correlated Fermi-Systems. Springer. ISBN 978-3-319-10825-4.

External links

- The strong-correlations puzzle - an article in Physicsworld.com.