Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program

The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP),[1] formerly known as the Food Stamp Program, provides food-purchasing assistance for low- and no-income people living in the U.S. It is a federal aid program, administered by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, under the Food and Nutrition Service (FNS), though benefits are distributed by each U.S. state's Division of Social Services or Children and Family Services.

SNAP benefits cost $74.1 billion in fiscal year 2014 and supplied roughly 46.5 million Americans with an average of $125.35 for each person per month in food assistance.[2] It is the largest nutrition program of the fifteen administered by FNS and is a critical component of the federal social safety net for low-income Americans.[3]

The amount of SNAP benefits received by a household depends on the household's size, income, and expenses. For most of its history, the program used paper-denominated "stamps" or coupons – worth US$1 (brown), $5 (blue), and $10 (green) – bound into booklets of various denominations, to be torn out individually and used in single-use exchange. Because of their 1:1 value ration with actual currency, the coupons were printed by the Bureau of Engraving and Printing. Their rectangular shape resembled a U.S. dollar bill (although about one-half the size), including intaglio printing on high-quality paper with watermarks. In the late 1990s, the Food Stamp Program was revamped, with some states phasing out actual stamps in favor of a specialized debit card system known as Electronic Benefit Transfer (EBT), provided by private contractors. EBT has been implemented in all states since June 2004. Each month, SNAP food stamp benefits are directly deposited into the household's EBT card account. Households may use EBT to pay for food at supermarkets, convenience stores, and other food retailers, including certain farmers' markets.[4]

History

First Food Stamp Program (FSP) (May 16, 1939 – Spring 1943)

The idea for the first FSP has been credited to various people, most notably U.S. Secretary of Agriculture Henry Wallace and the program's first administrator, Milo Perkins.[5] Of the program, Perkins said, "We got a picture of a gorge, with farm surpluses on one cliff and under-nourished city folks with outstretched hands on the other. We set out to find a practical way to build a bridge across that chasm."[6] The program operated by permitting people on relief to buy orange stamps equal to their normal food expenditures; for every US$1 worth of orange stamps purchased, fifty cents' worth of blue stamps were received. Orange stamps could be used to buy any food; blue stamps could be used only to buy food determined by the Department to be surplus.

Over the course of nearly four years, the first FSP reached approximately 20 million people at one time or another in nearly half of the counties in the U.S. at a total cost of $262 million. At its peak, the program assisted 4 million people simultaneously. The first recipient was Mabel McFiggin of Rochester, New York; the first retailer to redeem the stamps was Joseph Mutolo; and the first retailer caught violating program rules was Nick Salzano in October 1939. The program ended when the conditions that brought the program into being (unmarketable food surpluses and widespread unemployment) ceased to exist.[7]

Pilot Food Stamp Program (1961–1964)

The eighteen years between the end of the first FSP and the inception of the next were filled with studies, reports, and legislative proposals. Prominent U.S. Senators actively associated with attempts to enact a food stamp program during this period included George Aiken, Robert M. La Follette, Jr., Hubert Humphrey, Estes Kefauver, and Stuart Symington. From 1954 on, U.S. Representative Leonor Sullivan strove to pass food-stamp-program legislation.

On September 21, 1959, P.L. 86-341 authorized the Secretary of Agriculture to operate a food-stamp system through January 31, 1962. The Eisenhower Administration never used the authority. However, in fulfillment of a campaign promise made in West Virginia, President John F. Kennedy's first Executive Order called for expanded food distribution and, on February 2, 1961, he announced that food stamp pilot programs would be initiated. The pilot programs would retain the requirement that the food stamps be purchased, but eliminated the concept of special stamps for surplus foods. A Department spokesman indicated the emphasis would be on increasing the consumption of perishables.

Of the program, U.S. Representative Leonor K. Sullivan of Missouri asserted, "...the Department of Agriculture seemed bent on outlining a possible food stamp plan of such scope and magnitude, involving some 25 million persons, as to make the whole idea seem ridiculous and tear food stamp plans to smithereens."[8][9]

Food Stamp Act of 1964

The Food Stamp Act of 1964 appropriated $75 million to 350,000 individuals in 40 counties and three cities. The measure drew overwhelming support from House Democrats, 90 percent from urban areas, 96 percent from the suburbs, and 87 percent from rural areas. Republican lawmakers opposed the initial measure: only 12 percent of urban Republicans, 11 percent from the suburbs, and 5 percent from rural areas voted affirmatively. President Lyndon B. Johnson hailed food stamps as "a realistic and responsible step toward the fuller and wiser use of an agricultural abundance."[10]

Rooted in congressional logrolling, the act was part of a larger appropriation that raised price supports for cotton and wheat. Rural lawmakers supported the program so that their urban colleagues would not dismantle farm subsidies. Food stamps, along with Medicaid, Head Start, and the Job Corps were foremost among the growing anti-poverty programs.

President Johnson called for a permanent food-stamp program on January 31, 1964, as part of his "War on Poverty" platform introduced at the State of the Union a few weeks earlier. Agriculture Secretary Orville Freeman submitted the legislation on April 17, 1964. The bill eventually passed by Congress was H.R. 10222, introduced by Congresswoman Sullivan. One of the members on the House Committee on Agriculture who voted against the FSP in Committee was then Representative Bob Dole.

As a Senator, Dole became a staunch supporter of the program, after he worked with George McGovern to produce a bipartisan solution to two of the main problems associated with food stamps: cumbersome purchase requirements and lax eligibility standards. Dole told Congress regarding the new provisions, “I am confident that this bill eliminates the greedy and feeds the needy.” The law was intended to strengthen the agricultural economy and provide improved levels of nutrition among low-income households; however, the practical purpose was to bring the pilot FSP under congressional control and to enact the regulations into law.

The major provisions were:

- The State Plan of Operation requirement and development of eligibility standards by States;

- They required that the recipients should purchase their food stamps, while paying the average money spent on food then receiving an amount of food stamps representing an opportunity more nearly to obtain a low-cost nutritionally adequate diet;

- The eligibility for purchase with food stamps of all items intended for human consumption except alcoholic beverages and imported foods (the House version would have prohibited the purchase of soft drinks, luxury foods, and luxury frozen foods);

- Prohibitions against discrimination on basis of race, religious creed, national origin, or political beliefs;

- The division of responsibilities between States (certification and issuance) and the Federal Government (funding of benefits and authorization of retailers and wholesalers), with shared responsibility for funding costs of administration; and

- Appropriations for the first year limited to $75 million; for the second year, to $100 million; and, for the third year, to $200 million.

The Agriculture Department estimated that participation in a national FSP would eventually reach 4 million, at a cost of $360 million annually, far below the actual numbers.

Program expansion: participation milestones in the 1960s and early 1970s

In April 1965, participation topped half a million. (Actual participation was 561,261 people.) Participation topped 1 million in March 1966, 2 million in October 1967, 3 million in February 1969, 4 million in February 1970, 5 million one month later in March 1970, 6 million two months later in May 1970, 10 million in February 1971, and 15 million in October 1974. Rapid increases in participation during this period were primarily due to geographic expansion.

Major legislative changes (early 1970s)

The early 1970s were a period of growth in participation, concern about the cost of providing food stamp benefits, and questions about administration, primarily timely certification. During this time, the issue was framed that would dominate food stamp legislation ever after: how to balance program access with program accountability. Three major pieces of legislation shaped this period, leading up to massive reform to follow:

P.L. 91-671 (January 11, 1971) established uniform national standards of eligibility and work requirements; required that allotments be equivalent to the cost of a nutritionally adequate diet; limited households' purchase requirements to 30 percent of their income; instituted an outreach requirement; authorized the Agriculture Department to pay 62.5 percent of specific administrative costs incurred by States; expanded the FSP to Guam, Puerto Rico, and the Virgin Islands of the United States; and provided $1.75 billion appropriations for Fiscal Year 1971.

Agriculture and Consumer Protection Act of 1973 (P.L. 93-86, August 10, 1973) required States to expand the program to every political jurisdiction before July 1, 1974; expanded the program to drug addicts and alcoholics in treatment and rehabilitation centers; established semi-annual allotment adjustments, SSI cash-out, and bi-monthly issuance; introduced statutory complexity in the income definition (by including in-kind payments and providing an accompanying exception); and required the Department to establish temporary eligibility standards for disasters.

P.L. 93-347 (July 12, 1974) authorized the Department to pay 50 percent of all states' costs for administering the program and established the requirement for efficient and effective administration by the States.

1974 nationwide program

In accordance with P.L. 93-86, the FSP began operating nationwide on July 1, 1974. (The program was not fully implemented in Puerto Rico until November 1, 1974.) Participation for July 1974 was almost 14 million.

Eligible access to Supplemental Security Income beneficiaries

Once a person is a beneficiary of the Supplemental Security Income (SSI) Program he (or she) may be automatically eligible for Food Stamps depending on his (or her) state’s laws. How much money in food stamps they receive also varies by state. Supplemental Security Income was created in 1974.[11]

Food Stamp Act of 1977

Both the outgoing Republican Administration and the new Democratic Administration offered Congress proposed legislation to reform the FSP in 1977. The Republican bill stressed targeting benefits to the neediest, simplifying administration, and tightening controls on the program; the Democratic bill focused on increasing access to those most in need and simplifying and streamlining a complicated and cumbersome process that delayed benefit delivery as well as reducing errors, and curbing abuse. The chief force for the Democratic Administration was Robert Greenstein, Administrator of the Food and Nutrition Service (FNS).

In Congress, major players were Senators George McGovern, Jacob Javits, Humphrey, and Dole and Congressmen Foley and Richmond. Amid all the themes, the one that became the rallying cry for FSP reform was "EPR"—eliminate the purchase requirement—because of the barrier to participation the purchase requirement represented. The bill that became the law (S. 275) did eliminate the purchase requirement. It also:

- eliminated categorical eligibility;

- established statutory income eligibility guidelines at the poverty line;

- established 10 categories of excluded income;

- reduced the number of deductions used to calculate net income and established a standard deduction to take the place of eliminated deductions;

- raised the general resource limit to $1,750;

- established the fair market value (FMV) test for evaluating vehicles as resources;

- penalized households whose heads voluntarily quit jobs;

- restricted eligibility for students and aliens;

- eliminated the requirement that households must have cooking facilities;

- replaced store due bills with cash change up to 99 cents;

- established the principle that stores must sell a substantial amount of staple foods if they are to be authorized;

- established the ground rules for Indian Tribal Organization administration of the FSP on reservations; and

- introduced demonstration project authority.

In addition to EPR, the Food Stamp Act of 1977 included several access provisions:

- using mail, telephone, or home visits for certification;

- requirements for outreach, bilingual personnel and materials, and nutrition education materials;

- recipients' right to submit applications the first day they attempt to do so;

- 30-day processing standard and inception of the concept of expedited service;

- SSI joint processing and coordination with AFDC;

- notice, recertification, and retroactive benefit protections; and

- a requirement for States to develop a disaster plan.

The integrity provisions of the new program included fraud disqualifications, enhanced Federal funding for States' anti-fraud activities, and financial incentives for low error rates.

The House Report for the 1977 legislation points out that the changes in the Food Stamp Program are needed without reference to upcoming welfare reform since "the path to welfare reform is, indeed, rocky...."

EPR was implemented January 1, 1979. Participation that month increased 1.5 million over the preceding month.

Cutbacks of the early 1980s

The large and expensive FSP proved to be a favorite subject of close scrutiny from both the Executive Branch and Congress in the early 1980s. Major legislation in 1981 and 1982 enacted cutbacks including:

- addition of a gross income eligibility test in addition to the net income test for most households;

- temporary freeze on adjustments of the shelter deduction cap and the standard deduction and constraints on future adjustments;

- annual adjustments in food stamp allotments rather than semi-annual;

- consideration of non-elderly parents who live with their children and non-elderly siblings who live together as one household;

- required periodic reporting and retrospective budgeting;

- prohibition against using Federal funds for outreach;

- replacing the FSP in Puerto Rico with a block grant for nutrition assistance;

- counting retirement accounts as resources;

- State option to require job search of applicants as well as participants; and

- increased disqualification periods for voluntary quitters.

Electronic Benefits Transfer (EBT) began in Reading, Pennsylvania, in 1984.

Mid-to-late 1980s

Recognition of the severe domestic hunger problem in the latter half of the 1980s led to incremental expansions of the FSP in 1985 and 1987, such as elimination of sales tax on food stamp purchases, reinstitution of categorical eligibility, increased resource limit for most households ($2,000), eligibility for the homeless, and expanded nutrition education. The Hunger Prevention Act of 1988 and the Mickey Leland Memorial Domestic Hunger Relief Act in 1990 foretold the improvements that would be coming. The 1988 and 1990 legislation accomplished the following:

- increasing benefits by applying a multiplication factor to Thrifty Food Plan costs;

- making outreach an optional activity for States;

- excluding advance earned income tax credits as income;

- simplifying procedures for calculating medical deductions;

- instituting periodic adjustments of the minimum benefit;

- authorizing nutrition education grants;

- establishing severe penalties for violations by individuals or participating firms; and

- establishing EBT as an issuance alternative.

Throughout this era, significant players were principally various committee chairmen: Congressmen Leland, Hall, Foley, Leon Panetta, and, de la Garza and Senator Patrick Leahy.

1993 Mickey Leland Childhood Hunger Relief Act

By 1993, major changes in food stamp benefits had arrived. The final legislation provided for $2.8 billion in benefit increases over Fiscal Years 1984-1988. Leon Panetta, in his new role as OMB Director, played a major role as did Senator Leahy. Substantive changes included:

- eliminating the shelter deduction cap beginning January 1, 1997;

- providing a deduction for legally binding child support payments made to nonhousehold members;

- raising the cap on the dependent care deduction from $160 to $200 for children under 2 years old and $175 for all other dependents;

- improving employment and training (E&T) dependent care reimbursements;

- increasing the FMV test for vehicles to $4,550 on September 1, 1994 and $4,600 on October 1, 1995, then annually adjusting the value from $5,000 on October 1, 1996;

- mandating asset accumulation demonstration projects; and

- simplifying the household definition.

Later participation milestones

In December 1979, participation finally surpassed 20 million. In March 1994, participation hit a new high of 28 million.

1996 welfare reform and subsequent amendments

The mid-1990s was a period of welfare reform. Prior to 1996, the rules for the cash welfare program, Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC), were waived for many states. With the enactment of the 1996 welfare reform act, called the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996 (PRWORA), AFDC, an entitlement program, was replaced that with a new block grant to states called Temporary Assistance to Needy Families (TANF).

Although the Food Stamp Program was reauthorized in the 1996 Farm Bill, the 1996 welfare reform made several changes to the program, including:

- eliminating eligibility to food stamps of most legal immigrants who had been in the country less than five years;

- placing a time limit on food stamp receipt of three out of 36 months for Able-bodied Adults Without Dependents (ABAWDs), who are not working at least 20 hours a week or participating in a work program;

- reducing the maximum allotments to 100 percent of the change in the Thrifty Food Plan (TFP) from 103 percent of the change in the TFP;

- freezing the standard deduction, the vehicle limit, and the minimum benefit;

- setting the shelter cap at graduated specified levels up to $300 by fiscal year 2001, and allowing states to mandate the use of the standard utility allowance;

- revising provisions for disqualification, including comparable disqualification with other means-tested programs; and

- requiring states to implement EBT before October 1, 2002.

As a result of all these changes, "participation rates plummeted" in the late 1990s, according to Slate online magazine.[12]

The Balanced Budget Act of 1997 (BBA) and the Agricultural Research, Education and Extension Act of 1998 (AREERA) made some changes to these provisions, most significantly:

- using additional Employment and Training (E&T) funds to providing work program opportunities for able-bodied adults without dependents;

- allowing states to exempt up to 15 percent of the able-bodied adults without dependents who would otherwise be ineligible;

- restoring eligibility for certain elderly, disabled, and minor immigrants who resided in the United States when the 1996 welfare reform act was enacted; and

- cutting administrative funding for states to account for certain administrative costs that previously had been allocated to the AFDC program and now were required to be allocated to the Food Stamp Program.

The fiscal year 2001 agriculture appropriations bill included two significant changes. The legislation increased the excess shelter cap to $340 in fiscal year 2001 and then indexed the cap to changes in the Consumer Price Index for All Consumers each year beginning in fiscal year 2002. The legislation also allowed states to use the vehicle limit they use in a TANF assistance program, if it would be result in a lower attribution of resources for the household.

Electronic Benefits Transfer

In the late 1990s, the Food Stamp Program was revamped, with some states phasing out actual stamps in favor of a specialized debit card system known as Electronic Benefit Transfer (EBT), provided by private contractors. Many states merged the use of the EBT card for public welfare programs as well, such as cash assistance. The move was designed to save the government money by not printing the coupons, make benefits available immediately instead of requiring the recipient to wait for mailing or picking up the booklets in person, and reduce theft and diversion.[4]

Renaming the Food Stamp Program

The 2008 farm bill renamed the Food Stamp Program as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (beginning October 2008) and replaced all references to "stamp" or "coupon" in federal law with "card" or "EBT."[13][14]

Temporary benefits increase from April 2009 to November 2013

SNAP benefits temporarily increased with the passage of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (ARRA), a federal stimulus package to help Americans affected by the Great Recession.[15] Beginning in April 2009 and continuing through the expansion's expiration on November 1, 2013, the ARRA appropriated $45.2 billion to increase monthly benefit levels to an average of $133.[15][16] This amounted to a 13.6 percent funding increase for SNAP recipients.[16]

This temporary expansion expired on November 1, 2013, resulting in a relative benefit decrease for SNAP households; on average, benefits decreased by 5 percent.[15] According to a Center on Budget and Policy Priorities report, the maximum monthly benefit for a family of four dropped from $668 to $632, while the maximum monthly benefit for an individual dropped from $200 to $189.[15]

Corporate influence and support

In June 2014, Mother Jones reported that "Overall, 18 percent of all food benefits money is spent at Walmart," and that Walmart had submitted a statement to the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission stating,

Our business operations are subject to numerous risks, factors, and uncertainties, domestically and internationally, which are outside our control. These factors include... changes in the amount of payments made under the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Plan and other public assistance plans, [and] changes in the eligibility requirements of public assistance plans.[17]

Companies that have lobbied on behalf of SNAP include PepsiCo, Coca-Cola, and the grocery chain Kroger. Kraft Foods, which receives "One-sixth [of its] revenues ... from food stamp purchases" also opposes food stamp cuts.[17]

Eligibility

Because SNAP is a mandatory, or entitlement, program, the federal government is required to fund the benefits of all eligible participants. There are income and resource requirements for SNAP, as well as specific requirements for immigrants, elderly persons and persons with disabilities.[18]

Income requirements

For income, individuals and households may qualify for benefits if they earn a gross monthly income that is 130% (or less) of the federal poverty level for a specific household size. For example: the SNAP-eligible gross monthly income is $1,245 or less for an individual. For a household of 4, the SNAP eligible gross monthly income is $2,552 or less. Gross monthly income is the amount an individual makes each month before any deductions, i.e. taxes, insurance, pensions, etc.[18]

Resource requirements

There is also a resource requirement for SNAP, although eligibility requirements vary slightly from state to state. Generally speaking, households may have up to $2,000 in a bank account or other countable sources. If at least one person is age 60 or older and/or has disabilities, households may have $3,250 in countable resources.[18]

Housing expenditure

The lack of affordable housing in urban areas means that money that could have been spent on food is spent on housing expenses. Housing is generally considered affordable when it costs 30% or less of total household income; rising housing costs have made this ideal difficult to attain.

This is especially true in New York City, where 28% of rent stabilized tenants spend more than half their income on rent.[19] Among lower income families the percentage is much higher. According to an estimate by the Community Service Society, 65% of New York City families living below the federal poverty line are paying more than half of their income toward rent.[20]

The current eligibility criteria attempt to address this, by including a deduction for "excess shelter costs." This applies only to households that spend more than half of their net income on rent. For the purpose of this calculation, a household's net income is obtained by subtracting certain deductions from their gross (before deductions) income. If the household's total expenditures on rent exceed 50% of that net income, then the net income is further reduced by the amount of rent that exceeds 50% of net income. For 2007, this deduction can be no more than $417, except in households that include an elderly or disabled person.[21] Deductions include:

- a standard deduction that is subtracted from income for all recipients,

- an earned income deduction reflecting taxes and work expenses,

- a deduction for dependent care expenses related to work or training (up to certain limits),

- a deduction for child support payments,

- a deduction for medical expenses above a set amount per month (only available to elderly and disabled recipients), and

- a deduction for excessively high shelter expenses.[22]

The adjusted net income, including the deduction for excess shelter costs, is used to determine whether a household is eligible for food stamps.

Immigrant status and eligibility

The 2002 Farm Bill restores SNAP eligibility to most legal immigrants that:

- Have lived in the country for 5 years; or

- Are receiving disability-related assistance or benefits; or

- Have children under 18

Certain non-citizens, such as those admitted for humanitarian reasons and those admitted for permanent residence, may also be eligible for SNAP. Eligible household members can get SNAP benefits even if there are other members of the household that are not eligible.[18]

Applying for SNAP benefits

To apply for SNAP benefits, an applicant must first fill out a program application and return it to the state or local SNAP office. Each state has a different application, which is usually available online. There is more information about various state applications processes, including locations of SNAP offices in various state, displayed on an interactive Outreach Map found on the FNS website.[23] Individuals who believe they may be eligible for SNAP benefits may use the Food and Nutrition Services’ SNAP Screening Tool, which can help gauge eligibility.

Eligible food items under SNAP

As per USDA rules, households can use SNAP benefits to purchase:

- Foods for the household to eat, such as:

- fruits and vegetables;

- breads and cereals;

- dairy products;

- meats, fish and;

- poultry

- Plants and seeds which are fit for household consumption.

Additionally, restaurants operating in certain areas may be permitted to accept SNAP benefits from eligible candidates like elderly, homeless or disabled people in return for affordable meals.

However, the USDA clearly mentions that households cannot use SNAP benefits to purchase the following:

- Wine, beer, liquor, cigarettes or tobacco

- Certain nonfood items like:

- soaps, paper products

- household supplies, and

- pet foods

- Hot foods

- Food items that are consumable in the store

- Vitamins and medicines[24]

Soft drinks, candy, cookies, snack crackers, and ice cream are food items and are therefore eligible items. Seafood, steak, and bakery cakes are also food items and are therefore eligible items.[24]

Energy drinks which have a nutrition facts label are eligible foods, but energy drinks which have a supplement facts label are classified by the FDA as supplements, and are therefore not eligible.[24]

Live animals and birds may not be purchased; but live fish and shellfish are eligible foods.[24] Pumpkins are eligible, but inedible gourds and solely ornamental pumpkins are not.[24]

Gift baskets containing both food and non-food items "are not eligible for purchase with SNAP benefits if the value of the non-food items exceeds 50 percent of the purchase price. Items such as birthday and other special occasion cakes are eligible as long as the value of non-edible decorations does not exceed 50 percent of the price."[24]

State options

States are allowed under federal law to administer SNAP in different ways. As of April 2015, the USDA had published eleven periodic State Options Reports outlining variations in how states have administered the program.[25] The USDA's most recent State Options Report, published in April 2015, summarizes:

SNAP's statutes, regulations, and waivers provide State agencies with various policy options. State agencies use this flexibility to adapt their programs to meet the needs of eligible, low‐income people in their States. Modernization and technology have provided States with new opportunities and options in administering the program. Certain options may facilitate program design goals, such as removing or reducing barriers to access for low-income families and individuals, or providing better support for those working or looking for work. This flexibility helps States better target benefits to those most in need, streamline program administration and field operations, and coordinate SNAP activities with those of other programs.[26]

Some areas of differences among states include: when and how frequently SNAP recipients must report household circumstances; on whether the state agency acts on all reported changes or only some changes; whether the state uses a simplified method for determining the cost of doing business in cases where an applicant is self‐employed; and whether legally obligated child support payments made to non‐household members are counted as an income exclusion rather than a deduction.[26]

State agencies also have an option on whether to call their program SNAP; whether to continue to refer to their program under its former name, the Food Stamp Program; or whether to choose an alternate name.[26] Among the 50 states plus the District of Columbia, 32 call their program SNAP; five continue to call the program the Food Stamp Program; and 16 have adopted their own name.[26] For example, California calls its SNAP implementation "CalFresh," while Arizona calls its program "Nutrition Assistance."[26]

States and counties with highest use of SNAP per capita

According to January 2015 figures reported by the Census Bureau and USDA and compiled by USA Today, the states and district with the most food stamp recipients per capita are:[27]

| State | % of population receiving SNAP benefits |

|---|---|

| District of Columbia | 22% |

| Mississippi | 21% |

| New Mexico | 22% |

| West Virginia | 20% |

| Oregon | 20% |

| Tennessee | 20% |

| Louisiana | 19% |

According to June 2009 figures reported by the state agencies, the USDA, and Census Bureau, and compiled by the New York Times, the individual counties with the highest levels of SNAP usage were:

| County (or equivalent) | % of population receiving SNAP benefits |

|---|---|

| Kusilvak Census Area, Alaska | 49% |

| Owsley County, Kentucky | 49% |

| Oglala Lakota County, South Dakota | 49% |

| Pemiscot County, Missouri | 47% |

| Todd County, South Dakota | 46% |

| Sioux County, North Dakota | 45% |

| Dunklin County, Missouri | 44% |

| East Carroll Parish, Louisiana | 43% |

| Humphreys County, Mississippi | 43% |

| Wolfe County, Kentucky | 42% |

| Perry County, Alabama | 41% |

| Phillips County, Arkansas | 39% |

| Rolette County, North Dakota | 39% |

| Ripley County, Missouri | 39% |

| Ziebach County, South Dakota | 39% |

Impact

During the recession of 2008, SNAP participation hit an all-time high. Arguing in support for SNAP, the Food Research and Action Center argued that “putting more resources quickly into the hands of the people most likely to turn around and spend it can both boost the economy and cushion the hardships on vulnerable people who face a constant struggle against hunger.”[28] Researchers have found that every $1 that is spent from SNAP results in $1.73 of economic activity. In California, the cost-benefit ratio is even higher: for every $1 spent from SNAP between $3.67 to $8.34 is saved in health care costs.[29][30][31] The Congressional Budget Office also rated an increase in SNAP benefits as one of the two most cost-effective of all spending and tax options it examined for boosting growth and jobs in a weak economy.[31]

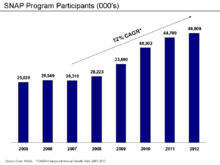

Participants

A summary statistical report indicated that an average of 47.6 million people used the program in FY 2013.[32] Nearly 72 percent of SNAP participants are in families with children; more than one-quarter of participants are in households with seniors or people with disabilities.[33]

As of 2013, more than 15% of the U.S. population receive food assistance, and more than 20% in Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, New Mexico, Oregon and Tennessee. Washington D.C. was the highest share of the population to receive food assistance at over 23%.[34]

According to the United States Department of Agriculture (based on a study of data gathered in Fiscal Year 2010), statistics for the food stamp program are as follows:[35]

- 49% of all participant households have children (17 or younger), and 55% of those are single-parent households.

- 15% of all participant households have elderly (age 60 or over) members.

- 20% of all participant households have non-elderly disabled members.

- The average gross monthly income per food stamp household is $731; The average net income is $336.

- 37% of participants are White, 22% are African-American, 10% are Hispanic, 2% are Asian, 4% are Native American, and 19% are of unknown race or ethnicity.[35]

Costs

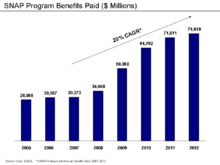

Amounts paid to program beneficiaries rose from $28.6 billion in 2005 to $76.6 billion in 2013. This increase was due to the high unemployment rate (leading to higher SNAP participation) and the increased benefit per person with the passing of ARRA. SNAP average monthly benefits increased from $96.18 per person to $133.08 per person. Other program costs, which include the Federal share of State administrative expenses, Nutrition Education, and Employment and Training, amounted to roughly $3.7 million in 2013.[4] There were cuts into the program's budget introduced in 2014 that were estimated to save $8.6 billion over 10 years. Some of the states are looking for measures within the states to balance the cuts, so they would not affect the recipients of the federal aid program.[36]

Food security and insecurity

While SNAP participants and other low-income nonparticipants spend similar amounts on food spending, SNAP participants tend to still experience greater food insecurity than nonparticipants. This is believed to be a reflection of welfare of individuals who take the time to apply for SNAP benefits than the shortcomings of SNAP. The theory behind this is that those households facing the greatest hardships are the most likely to bear of the burden of applying for program benefits. Therefore, SNAP participants tend to be, on average, less food secure than other low-income nonparticipants.[37]

Self-selection by more food-needy households into SNAP makes it difficult to observe positive effects on food security from survey data.[38] While SNAP participants and other low-income nonparticipants spend similar amounts on food spending, SNAP participants tend to still experience greater food insecurity than nonparticipants. This is believed to be a reflection of welfare of individuals who take the time to apply for SNAP benefits than the shortcomings of SNAP. In other words, households facing the greatest hardships are the most likely to bear of the burden of applying for program benefits.[37] Statistical models that control for this endogeneity suggest that SNAP receipt reduces the likelihood of being food insecure and very food insecure by roughly 30 percent and 20 percent, respectively.[39]

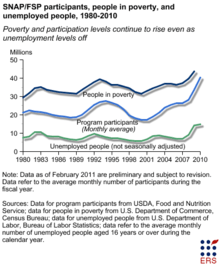

Poverty

Because SNAP is a means tested, entitlement program, participation rates are closely related to the number of individuals living in poverty in a given time period. In periods of economic recession, SNAP enrollment tends to increase and in periods of prosperity, SNAP participation tends to be lower.[37] Unemployment is therefore also related to SNAP participation. However, ERS data shows that poverty and SNAP participation levels have continued to rise following the 2008 recession, even though unemployment rates have leveled off. Poverty levels are the strongest correlates for program participation.

A 2016 study found that SNAP benefits lead to greater expenditures on housing, transportation, and education by beneficiaries.[40]

Income maintenance

The purpose of the Food Stamp Program as laid out in its implementation was to assist low-income households in obtaining adequate and nutritious diets. According to Peter H. Rossi, a sociologist whose work involved evaluation of social programs, "the program rests on the assumption that households with restricted incomes may skimp on food purchases and live on diets that are inadequate in quantity and quality, or, alternatively skimp on other necessities to maintain an adequate diet".[41] Food stamps, as many like Rossi, MacDonald, and Eisinger contend, are used not only for increasing food but also as income maintenance. Income maintenance is money that households are able to spend on other things because they no longer have to spend it on food. According to various studies shown by Rossi, because of income maintenance only about $0.17–$0.47 more is being spent on food for every food stamp dollar than was spent prior to individuals receiving food stamps.[42]

Diet quality

Studies are inconclusive as to whether SNAP has a direct effect on the nutritional quality of food choices made by participants. Unlike other federal programs that provide food subsidies, i.e. the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program for Women, Infants and Children (WIC), SNAP does not have nutritional standards for purchases. Critics of the program suggest that this lack of structure represents a missed opportunity for public health advancement and cost containment.[43][44] In April, 2013, the USDA research body, the Economic Research Service (ERS), published a study that examined diet quality in SNAP participants compared to low-income nonparticipants. The study revealed a difference in diet quality between SNAP participants and low-income nonparticipants, finding that SNAP participants score slightly lower on the Healthy Eating Index (HEI) than nonparticipants. The study also concluded that SNAP increases the likelihood that participants will consume whole fruit by 23 percentage points. However, the analysis also suggests that SNAP participation decreases participants' intake of dark green/orange vegetables by a modest amount.[45]

A 2016 study found no evidence that SNAP increased expenditures on tobacco by beneficiaries.[40]

Macroeconomic effect

The USDA's Economic Research Service explains: "SNAP is a counter-cyclical government assistance program—it provides assistance to more low-income households during an economic downturn or recession and to fewer households during an economic expansion. The rise in SNAP participation during an economic downturn results in greater SNAP expenditures which, in turn, stimulate the economy."[46]

In 2011, Secretary of Agriculture Tom Vilsack gave a statement regarding SNAP benefits: "Every dollar of SNAP benefits generates $1.84 in the economy in terms of economic activity."[47] Vilsack's estimate was based on a 2002 USDA study which found that "ultimately, the additional $5 billion of FSP (Food Stamp Program) expenditures triggered an increase in total economic activity (production, sales, and value of shipments) of $9.2 billion and an increase in jobs of 82,100," or $1.84 stimulus for every dollar spent.[48]

A January 2008 report by Moody's Analytics chief economist Mark Zandi analyzed measures of the Economic Stimulus Act of 2008 and found that in a weak economy, every $1 in SNAP expenditures generates $1.73 in real GDP increase, making it the most effective stimulus among all the provisions of the act, including both tax cuts and spending increases.[49][50]

A 2010 report by Kenneth Hanson published by the USDA's Economic Research Service estimated that a $1 billion increase in SNAP expenditures increases economic activity (GDP) by $1.79 billion (i.e., the GDP multiplier is 1.79).[51] The same report also estimated that the "preferred jobs impact ... are the 8,900 full-time equivalent jobs plus self-employed or the 9,800 full-time and part-time jobs plus self-employed from $1 billion of SNAP benefits."[51]

Local economic effects

In March 2013, the Washington Post reported that one-third of Woonsocket, Rhode Island's population used food stamps, putting local merchants on a "boom or bust" cycle each month when EBT payments were deposited. The Post stated that "a federal program that began as a last resort for a few million hungry people has grown into an economic lifeline for entire towns."[52] And this growth "has been especially swift in once-prosperous places hit by the housing bust."[53]

In addition to local town merchants, national retailers are starting to take in an increasing large percentage of SNAP benefits. For example, "Walmart estimates it takes in about 18% of total U.S. outlays on food stamps."[54]

Fraud and abuse

In March 2012, the USDA published its fifth report in a series of periodic analyses to estimate the extent of trafficking in SNAP; that is, selling or otherwise converting SNAP benefits for cash payouts. Although trafficking does not increase costs to the Federal Government,[55][56][57] it diverts benefits from their intended purpose of helping low-income families access a nutritious diet. The FNS aggressively acts to control trafficking by using SNAP purchase data to identify suspicious transaction patterns, conducting undercover investigations, and collaborating with other investigative agencies.

Trafficking diverted an estimated one cent of each SNAP dollar ($330 million annually) from SNAP benefits between 2006 and 2008. Trafficking has declined over time from nearly 4 percent in the 1990s. About 8.2 percent of all stores trafficked from 2006 to 2008 compared to the 10.5 percent of SNAP authorized stores involved in trafficking in 2011.[58] A variety of store characteristics and settings were related to the level of trafficking. Although large stores accounted for 87.3 percent of all SNAP redemptions, they only accounted for about 5.4 percent of trafficking redemptions. Trafficking was much less likely to occur among publicly owned than privately owned stores and was much less likely among stores in areas with less poverty rather than more. The total annual value of trafficked benefits increased at about the same rate as overall program growth. The current estimate of total SNAP dollars trafficked is higher than observed in the previous 2002–2005 time period. This increase is consistent, however, with the almost 37 percent growths in average annual SNAP benefits from the 2002–2005 study periods to the most recent one. The methodology used to generate these estimates has known limitations. However, given variable data and resources, it is the most practical approach available to FNS. Further improvements to SNAP trafficking estimates would require new resources to assess the prevalence of trafficking among a random sample of stores.[59]

The USDA report released in August 2013 says the dollar value of trafficking increased to 1.3 percent, up from 1 percent in the USDA's 2006-2008 survey,[58] and "About 18 percent of those stores classified as convenience stores or small groceries were estimated to have trafficked. For larger stores (supermarkets and large groceries), only 0.32 percent were estimated to have trafficked. In terms of redemptions, about 17 percent of small groceries redemptions and 14 percent of convenience store redemptions were estimated to have been trafficked. This compares with a rate of 0.2 percent for large stores."[60]

The USDA, in December 2011, announced new policies to attempt to curb waste, fraud, and abuse. These changes will include stiffer penalties for retailers who are caught participating in illegal or fraudulent activities.[61] “The department is proposing increasing penalties for retailers and providing states with access to large federal databases they would be required to use to verify information from applicants. SNAP benefit fraud, generally in the form of store employees buying EBT cards from recipients is widespread in urban areas, with one in seven corner stores engaging in such behavior, according to a recent government estimate. There are in excess of 200,000 stores, and we have 100 agents spread across the country. Some do undercover work, but the principal way we track fraud is through analyzing electronic transactions” for suspicious patterns, USDA Under Secretary Kevin Concannon told The Washington Times.[62] Also, states will be given additional guidance that will help develop a tighter policy for those seeking to effectively investigate fraud and clarifying the definition of trafficking.

According to the Government Accountability Office, at a 2009 count, there was a payment error rate of 4.36% of SNAP benefits down from 9.86% in 1999.[63] A 2003 analysis found that two-thirds of all improper payments were the fault of the caseworker, not the participant.[63] There are also instances of fraud involving exchange of SNAP benefits for cash and/or for items not eligible for purchase with EBT cards.[64] In 2011, the Michigan program raised eligibility requirements for full-time college students, to save taxpayer money and to end student use of monthly SNAP benefits.[65]

In Maine, incidents of recycling fraud have occurred in the past where individuals once committed fraud by using their EBT cards to buy canned or bottled beverages (requiring a deposit to be paid at the point of purchase for each beverage container), dump the contents out so the empty beverage container could be returned for deposit redemption, and thereby, allowed these individuals to eventually purchase non-EBT authorized products with cash from the beverage container deposits.[66]

The State of Utah developed a system called "eFind" to monitor, evaluate and cross-examine qualifying and reporting data of recipients assets. Utah’s eFind system is a “back end,” web-based system that gathers, filters, and organizes information from various federal, state, and local databases. The data in eFind is used to help state eligibility workers determine applicants’ eligibility for public assistance programs, including Medicaid, CHIP, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), and child care assistance.[67] When information is changed in one database, the reported changes become available to other departments utilizing the system. This system was developed with federal funds and it is available to other states free of charge.

The USDA only reports direct fraud and trafficking in benefits, which was officially estimated at $858 million in 2012. The Cato Institute reports that there was another $2.2 billion in erroneous payouts in 2009. Cato also reported that the erroneous payout rate dropped significantly from 5.6 percent in 2007 to 3.8 percent in 2011.

Role of SNAP in healthy diets

Background

The 2008 Farm Bill authorized $20 million to be spent on pilot projects to determine whether incentives provided to SNAP recipients at the point-of-sale would increase the purchase of fruits, vegetables, or other healthful foods.[68] Fifteen states expressed interest in having the pilot program and, ultimately, five states submitted applications to be considered for HIP. Hampden County, Massachusetts was selected as the Healthy Incentives Pilot (HIP) site. HIP is designed to take place from August 2010 to April 2013 with the actual operation phase of the pilot program scheduled to last 15 months, from November 2011 to January 2013.[69]

HIP offers select SNAP recipients a 30% subsidy on produce, which is credited to the participant’s EBT card, for 15 months. 7,500 households will participate HIP and an equal number will not; the differences between the two groups will be analyzed to see the effects of the program.[70] Produce, under the HIP, is defined as fresh, frozen, canned, or dried fruits and vegetables that do not have any added sugar, salt, fat, or oil.

Administrative responsibility

The Massachusetts Department of Transitional Assistance (DTA) is the state agency responsible for SNAP. DTA has recruited retailers to take part in HIP and sell more produce, planned for the EBT system change with the state EBT vendor, and hired six new staff members dedicated to HIP. DTA has agreed to provide FNS with monthly reports, data collection and evaluation.

Proposals to restrict "junk food" or "luxury items"

Periodically, proposals have been raised to restrict SNAP benefits from being used to purchase various categories or types of food which have been criticized as "junk food" or "luxury items." However, Congress and the Department of Agriculture have repeatedly rejected such proposals on both administrative burden and personal freedom grounds. The Food and Nutrition Service noted in 2007 that no federal standards exist to determine which foods should be considered "healthy" or not, that "vegetables, fruits, grain products, meat and meat alternatives account for nearly three-quarters of the money value of food used by food stamp households" and that "food stamp recipients are no more likely to consume soft drinks than are higher-income individuals, and are less likely to consume sweets and salty snacks."[71] Thomas Farley and Russell Sykes argued that the USDA should reconsider the possibility of restricting "junk food" purchases with SNAP in order to encourage healthy eating, along with incentivizing the purchase of healthy items through a credit or rebate program that makes foods such as fresh vegetables and meats cheaper. They also noted that many urban food stores do a poor job of stocking healthy foods and instead favor high-profit processed items.[72]

See also

- Food, Conservation, and Energy Act of 2008 (2007 Farm Bill)

- Food stamp challenge

- Lone Star Card (Texas Electronic Benefit Transfer)

- National School Lunch Act

- Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children (WIC)

- Department of Agriculture v. Moreno, 413 U.S. 528 (1973)

- Lyng v. Castillo, 477 U.S. 635 (1986)

General:

References

- ↑ Nutrition Assistance Program Home Page, U.S. Department of Agriculture (official website), March 3, 2011 (last revised). Accessed March 4, 2011.

- ↑ "SNAP Monthly Data". Fns.usda.gov. 6 February 2015. Retrieved 2 March 2015.

- ↑ Wilde, Parke (May 2012). "The New Normal: The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP)". Am. J. Agr. Econ. 95 (2): : 325–331. doi:10.1093/ajae/aas043.

- 1 2 3 "Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program". USDA. Retrieved 15 December 2013.

- ↑ "A Short History of SNAP". fns.usda.gov. United States department of Agriculture. Retrieved 16 August 2015.

- ↑ "Putting the 'Food' in Food Stamps: Food Eligibility in the Food Stamps Program from 1939 to 2012" (PDF).

- ↑ "A Short History of SNAP - Food and Nutrition Service". Retrieved 5 January 2016.

- ↑ "SNAP Legislation". Fns.usda.gov. Retrieved 2013-12-31.

- ↑ "Food Stamps" (PDF). Robert J. Dole Archive & Special Collections. Robert J. Dole Institute of Politics. Retrieved 30 October 2014.

- ↑ Frederic N. Cleaveland, Congress and Urban Problems (New York: Brookings Institution, 1969), p. 305

- ↑ "Understanding Supplemental Security Income SSI and Other Government Programs". Social Security Online – USA.gov.

- ↑ Lowery, Annie (2010-12-10) A Satisfying Subsidy: How conservatives learned to love the federal food stamps program, Slate

- ↑ "Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program: 2008 Farm Bill" (November 30, 2011). United States Department of Agriculture.

- ↑ "H.R.6124 – Title: To provide for the continuation of agricultural and other programs of the Department of Agriculture through fiscal year 2012, and for other purposes.", U.S. Library of Congress, undated. Accessed May 20, 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 Brad Plumer, Food stamps will get cut by $5 billion this week — and more cuts could follow, Washington Post (October 28, 2013).

- 1 2 Reid Wilson, After Friday, states will lose $5 billion in food aid, Washington Post (October 28, 2013).

- 1 2 Van Buren, Peter (2014-06-06). "9 Questions About Poverty, Answered". Mother Jones. Retrieved 2014-06-07.

- 1 2 3 4 "Eligibility". USDA. Retrieved 16 December 2013.

- ↑ "Housing Conditions and Problems In New York City: An Analysis of the 1996 Housing and Vacancy Survey". Housingnyc.com. Retrieved 2013-12-31.

- ↑ "Making The Rent: Who's At Risk?" (PDF). Cssny.org. Retrieved 2013-12-31.

- ↑ Fact Sheet on Resources, Income, and Benefits Archived March 10, 2010, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑

This article incorporates public domain material from the Congressional Research Service document "Report for Congress: Agriculture: A Glossary of Terms, Programs, and Laws, 2005 Edition" by Jasper Womach.

This article incorporates public domain material from the Congressional Research Service document "Report for Congress: Agriculture: A Glossary of Terms, Programs, and Laws, 2005 Edition" by Jasper Womach.

- ↑ "Where is my local office?". Retrieved 5 January 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Eligible Food Items, United States Department of Agriculture (official website), December 20, 2013 (Last modified), Accessed July 7, 2014.

- ↑ State Options Report, United States Department of Agriculture.

- 1 2 3 4 5 State Options Report, United States Department of Agriculture (11th ed.), April 2015.

- ↑ Erika Rawes, States with the most people on food stamps, Cheat Sheet/USA Today (January 17, 2015).

- ↑ "SNAP/Food Stamps Provide Real Stimulus « Food Research & Action Center". Retrieved 5 January 2016.

- ↑ Joy, Amy Block (October–December 2006). "Cost-benefit analysis conducted for nutrition education in California". California Agriculture journal. 60 (4): 185–191. Retrieved April 20, 2015.

- ↑ "Food stamps offer best stimulus - study". Retrieved 2 December 2013.

- 1 2 Rosenbaum, Dottie (11 March 2013). "SNAP Is Effective and Efficient". Retrieved 2 December 2013.

Economists consider SNAP one of the most effective forms of economic stimulus. Moody’s Analytics estimates that in a weak economy, every dollar increase in SNAP benefits generates about $1.70 in economic activity. Similarly, CBO rated an increase in SNAP benefits as one of the two most cost-effective of all spending and tax options it examined for boosting growth and jobs in a weak economy.

- ↑ "Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP)". Retrieved 5 January 2016.

- ↑ "Policy Basics: Introduction to the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP)". Center for Budget and Policy Priorititys. March 2013. Retrieved 16 December 2013.

- ↑ Phil Izzo (12 August 2013). "Food-Stamp Use Rises; Some 15% Get Benefits". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 12 August 2013.

- 1 2 "Characteristics of Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program Households: Fiscal Year 2010" (PDF). United States Department of Agriculture. Retrieved 2012-01-05.

- ↑ Jalonick, Mary. "Only 4 states will see cuts to food stamps". Associated Press. Retrieved 18 September 2014.

- 1 2 3 Wilde, Parke (2013). Food Policy in the US. Routledge. ISBN 978-1849714297.

- ↑ Nord, Mark; Golla, Marie (October 2009). "Does SNAP Decrease Food Insecurity? Untangling the Self-Selection Effect". Economic Research Report No. (ERR-85): 23.

- ↑ Ratcliffe, Caroline; Signe-Mary McKernan (March 2010). "How Much Does SNAP Reduce Food Insecurity?" (PDF). The Urban Institute.

- 1 2 Kim, Jiyoon. "Do SNAP participants expand non-food spending when they receive more SNAP Benefits?—Evidence from the 2009 SNAP benefits increase". Food Policy. doi:10.1016/j.foodpol.2016.10.002.

- ↑ Rossi, Peter H. Feeding the Poor: Assessing Federal Food Aid. Washington: AEI Press, 1998 p.28

- ↑

- Rossi, Peter H. Feeding the Poor: Assessing Federal Food Aid. Washington: AEI Press, 1998. p.36

- ↑ "Feeding the Poor". Welfareacademy.org. Retrieved 2013-12-31.

- ↑ Articles by Lane, S. "Food Distribution and Food Stamp Program Effects on Food Consumption and Nutritional "Achievement" of Low Income Persons in Kern County, California". Ajae.oxfordjournals.org. Retrieved 2013-12-31.

- ↑ Gregory, Christian; Ver Ploeg, Michele; Andrews, Margaret; Coleman-Jensen, Alisha (April 2013). "Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) Participation Leads to Modest Changes in Diet Quality" (PDF). Economic Research Service. Retrieved 14 December 2013.

- ↑ Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) Linkages with the General Economy, Economic Research Service, United States Department of Agriculture].

- ↑ Real Clear Politics: Obama Ag Secretary Vilsack: Food Stamps Are A "Stimulus." August 16, 2011.

- ↑ "Effects of Changes in Food Stamp Expenditures Across the U.S. Economy". U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. 2002. Retrieved 2011-09-30.

- ↑ Mark Zandi, Assessing the Macroeconomic Impact of Economic Impact of Fiscal Stimulus 2008, Moody's Analytics (January 2008), pp. 3-4.

- ↑ Food stamps offer best stimulus - study, CNN (January 29, 2008).

- 1 2 "The Food Assistance National Input-Output Multiplier (FANIOM) Model and Stimulus Effects of SNAP (Economic Research Report No. (ERR-103)". Economic Research Service, United States Department of Agriculture. October 2010. p. iv. Retrieved 2013-12-31.

- ↑ "Food stamps put Rhode Island town on monthly boom-and-bust cycle". The Washington Post. 2013-03-16. Retrieved 2013-04-14.

- ↑ "Food Stamp Use Soars, and Stigma Fades". NYTimes. 2009-11-29. Retrieved 2013-12-31.

- ↑ Banjo, Shelly (2013-11-04). "WSJ: Retailers Brace for Reduction in Food Stamps". Online.wsj.com. Retrieved 2013-12-31.

- ↑ "The Extent of Trafficking in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program: 2009-2011". Retrieved 2014-03-09.

- ↑ "Feds: More Americans selling their food stamps for cash". Retrieved 2014-03-09.

- ↑ "Feds: Food Stamp Trafficking Up 30% From 2008 to 2011". Retrieved 2014-03-09.

- 1 2 "The Extent of Trafficking in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program: 2009–2011" (PDF). Retrieved 2013-12-31.

- ↑ "United States Department of Agriculture - Home" (PDF). Fns.usda.gov. Retrieved 2013-10-13.

- ↑ "United States Department of Agriculture - Home" (PDF). Fns.usda.gov. Retrieved 2013-10-13.

- ↑ "Hearing To Review Updates On Usda Inspector General Audits, Including Snap Fraud Detection Efforts And It Compliance". Gpo.gov. Retrieved 2013-10-13.

- ↑ "Kevin Concannon - Bio, News, Photos". Washington Times. Retrieved 2013-10-13.

- 1 2 Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program: Payment Errors and Trafficking Have Declined, but Challenges Remain GAO report number GAO-10-956T, July 28, 2010

- ↑ AP Photo. "Food-stamp fraud: Detroit-area stores swipe millions from aid program". Mlive.com. Retrieved 2013-12-31.

- ↑ "New Restrictions on Bridge Card Use by College Students". Michiganpolicy.com. 2011-02-13. Retrieved 2013-12-31.

- ↑ "Bangor food stamp scam dumps water for deposit". New.bangordailynews.com. 2010-08-19. Retrieved 2013-12-31.

- ↑ http://www.insurekidsnow.gov/professionals/events/2011_conference/utah_department_of_workforce_services_efind_508.pdf.pdf

- ↑ "Healthy Incentives Program webpage on U.S. Department of Agriculture website". Fns.usda.gov. Retrieved 2013-12-31.

- ↑ "Healthy Incentives Program – Timeline webpage on U.S. Department of Agriculture website". Fns.usda.gov. Retrieved 2013-12-31.

- ↑ "Healthy Incentives Program Evaluation webpage on U.S. Department of Agriculture website". Fns.usda.gov. Retrieved 2013-12-31.

- ↑ IMPLICATIONS OF RESTRICTING THE USE OF FOOD STAMP BENEFITS - SUMMARY, Food and Nutrition Service, March 2007

- ↑ See No Junk Food, Buy No Junk Food. Sykes, Russell & Thomas Farley, The New York Times, 21 March 2015

Sources

- United States Department of Health and Human Services, "2002 Indicators of Welfare Dependence Appendix A: Program Data: Food Stamp Program"

- Article based on the USDA Web publication: A Short History of the Food Stamp Program

- Eisinger, Peter K. Toward an end to hunger in America. Washington: The Brookings Institution, 1998.

- MacDonald, Maurice. Food, Stamps, and Income Maintenance. New York: Academic Pres, Inc, 1977.

- Gundersen, Craig; LeBlanc, Michael; Kuhn, Betsey, "The Changing Food Assistance Landscape: The Food Stamp Program in a Post-Welfare Reform Environment, United States Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Economics Report No. (AER773) 36 pp, March 1999

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program. |

-

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the United States Department of Agriculture.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the United States Department of Agriculture. - Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) at Food and Nutrition Service

- History of the Food Stamp Program video from Center on Budget and Policy Priorities

- Center on Budget and Policy Priorities-Everything You Ever Wanted to Know About SNAP-July 2013

- SNAP/Food Stamp Challenges

- Food Stamp Fraud - Supermarket Owner Imprisoned for Multi-Million-Dollar Scam (FBI)