Tangent half-angle substitution

In integral calculus, the tangent half-angle substitution is a substitution used for finding antiderivatives, and hence definite integrals, of rational functions of trigonometric functions. No generality is lost by taking these to be rational functions of the sine and cosine. Michael Spivak wrote that "The world's sneakiest substitution is undoubtedly" this technique.[1]

Euler and Weierstrass

Various books call this the Weierstrass substitution, after Karl Weierstrass (1815 – 1897), without citing any occurrence of the substitution in Weierstrass' writings,[2][3][4] but the technique appears well before Weierstrass was born, in the work of Leonhard Euler (1707 – 1783).[5]

The substitution

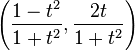

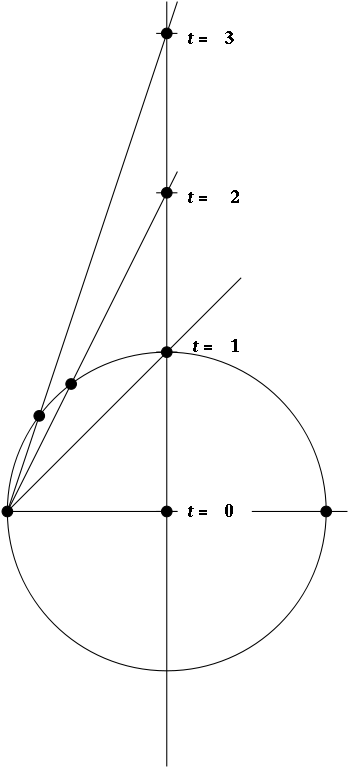

One starts with the problem of finding an antiderivative of a rational function of the sine and cosine; and replaces sin x, cos x, and the differential dx with rational functions of a variable t and the product of a rational function of t with the differential dt, as follows:[6]

Derivation

Let

By the double-angle formula for the sine function,

By the double-angle formula for the cosine function,

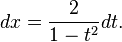

The differential dx can be calculated as follows:

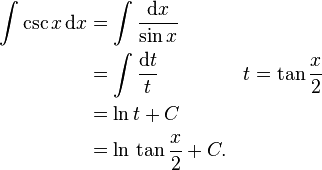

Examples

First example

Second example: a definite integral

In the first line, one does not simply substitute  for both limits of integration. The singularity (in this case, a vertical asymptote) of

for both limits of integration. The singularity (in this case, a vertical asymptote) of  at

at  must be taken into account.

must be taken into account.

Geometry

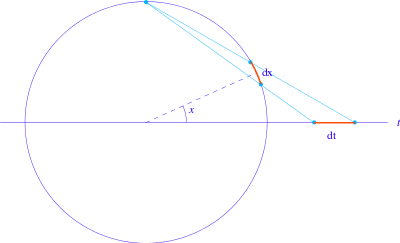

As x varies, the point (cos x, sin x) winds repeatedly around the unit circle centered at (0, 0). The point

goes only once around the circle as t goes from −∞ to +∞, and never reaches the point (−1, 0), which is approached as a limit as t approaches ±∞. As t goes from −∞ to −1, the point determined by t goes through the part of the circle in the third quadrant, from (−1, 0) to (0, −1). As t goes from −1 to 0, the point follows the part of the circle in the fourth quadrant from (0, −1) to (1, 0). As t goes from 0 to 1, the point follows the part of the circle in the first quadrant from (1, 0) to (0, 1). Finally, as t goes from 1 to +∞, the point follows the part of the circle in the second quadrant from (0, 1) to (−1, 0).

Here is another geometric point of view. Draw the unit circle, and let P be the point (−1, 0). A line through P (except the vertical line) is determined by its slope. Furthermore, each of the lines (except the vertical line) intersects the unit circle in exactly two points, one of which is P. This determines a function from points on the unit circle to slopes. The trigonometric functions determine a function from angles to points on the unit circle, and by combining these two functions we have a function from angles to slopes.

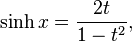

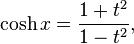

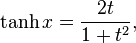

Hyperbolic functions

As with other properties shared between the two functions, it is also possible to construct a similar form:

See here for more information.

See also

Notes and references

- ↑ Michael Spivak, Calculus, Cambridge University Press, 2006, pages 382–383.

- ↑ Gerald L. Bradley and Karl J. Smith, Calculus, Prentice Hall, 1995, pages 462, 465, 466

- ↑ Christof Teuscher, Alan Turing: Life and Legacy of a Great Thinker, Springer, 2004, pages 105–6

- ↑ James Stewart, Calculus: Early Transcendentals, Brooks/Cole, Apr 1, 1991, page 436

- ↑ Leonhard Euler, Institutiionum calculi integralis volumen primum, 1768, E342, Caput V, paragraph 261. See http://www.eulerarchive.org/

- ↑ James Stewart, Calculus: Early Transcendentals, Brooks/Cole, 1991, page 439

![\begin{align}

\sin x & = \frac{2t}{1 + t^2} \\[8 pt]

\cos x & = \frac{1 - t^2}{1 + t^2} \\[8 pt]

\mathrm{d}x & = \frac{2 \,\mathrm{d}t}{1 + t^2}.

\end{align}](../I/m/ebeec6cf5018535f86001e2619dc3e9f.png)

![\begin{align}

\sin x&=2\sin\frac{x}{2}\cos\frac{x}{2}\\[8 pt]

&=2t\cos^2\frac{x}{2}\\[8 pt]

&=\frac{2t}{\sec^2\frac{x}{2}}\\[8 pt]

&=\frac{2t}{1+t^2}.

\end{align}](../I/m/be5e847cd0a0fd14eb67e522a2b05a35.png)

![\begin{align}

\cos x&=1-2\sin^2\frac{x}{2}\\[8 pt]

&=1-2t^2\cos^2\frac{x}{2}\\[8 pt]

&=1-\frac{2t^2}{\sec^2\frac{x}{2}}\\[8 pt]

&=1-\frac{2t^2}{1+t^2}\\[8 pt]

&=\frac{1-t^2}{1+t^2}.

\end{align}](../I/m/d13fc1ad3c013384fe8aaea2a17bee3f.png)

![\begin{align}

\frac{\mathrm{d}t}{\mathrm{d}x}&=\frac{1}{2}\sec^2\frac{x}{2}\\[8 pt]

&=\frac{1+t^2}{2}\\[8 pt]

\Rightarrow\mathrm{d}x&=\frac{2\,\mathrm{d}t}{1+t^2}.

\end{align}](../I/m/e8cd00cad9d773b157d8926608d22b61.png)

![\begin{align}

\int_0^{2\pi}\frac{\mathrm{d}x}{2+\cos x} & = \int_{x=0}^{x=\pi}\frac{\mathrm{d}x}{2+\cos x}+\int_{x=\pi}^{x=2\pi}\frac{\mathrm{d}x}{2+\cos x} \\[6pt]

&=\int_{t=0}^{t=\infty}\frac{\mathrm{d}x}{2+\cos x}+\int_{t=-\infty}^{t=0}\frac{\mathrm{d}x}{2+\cos x}&t&=\tan\frac{x}{2} \\[6pt]

&=\int_{t=-\infty}^{t=\infty}\frac{\mathrm{d}x}{2+\cos x} \\[6pt]

&=\int_{-\infty}^{\infty}\frac{2\,\mathrm{d}t}{3+t^2} \\[6pt]

&=\frac{2}{\sqrt 3}\int_{-\infty}^{\infty}\frac{\mathrm{d}u}{1+u^2}&t&=u\sqrt 3\\[6pt]

&=\frac{2\pi}{\sqrt 3}.

\end{align}](../I/m/71206c5ef695a7a9f3b6b6defde11175.png)