Ted Healy

| Ted Healy | |

|---|---|

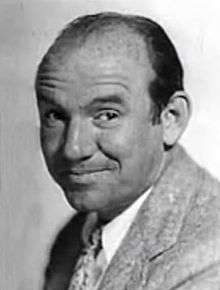

in the trailer for The Casino Murder Case | |

| Born |

Ernest Lea Nash October 1, 1896 Kaufman, Texas, U.S. |

| Died |

December 21, 1937 (aged 41) Los Angeles, California, U.S. |

| Cause of death | Nephritis |

| Resting place | Calvary Cemetery, East Los Angeles |

| Nationality | American |

| Occupation | Comedian, actor |

| Years active | 1912—1937 |

| Spouse(s) |

Betty Brown (m. 1922–32) Betty Hickman (m. 1936–37) |

| Children | 1 |

Ted Healy (October 1, 1896 – December 21, 1937) was an American vaudeville performer, comedian, and actor. Though he is chiefly remembered as the creator of The Three Stooges and the style of slapstick comedy that they later made famous, he had a successful stage and film career of his own, and was cited as a formative influence by several later comedy stars.

Early life

Sources conflict on Healy's precise birth name and birthplace, but according to baptism records, he was born Ernest (or Earnest) Lea Nash on October 1, 1896 in Kaufman, Texas.[1] He attended Holy Innocents' School in Houston before the family moved to New York in 1908. While in New York, he attended high school at De La Salle Institute. Nash initially intended to follow in the footsteps of his father and pursue a career in business, but eventually decided on the stage.[2]

Show business career

Nash made his first foray into show business in 1912, at the age of 15. He and his childhood friend Moses Horwitz (later known as Moe Howard) joined the Annette Kellerman Diving Girls, a vaudeville act that included four boys. The work ended quickly after an accident on stage, and Nash and Howard went their separate ways. Nash developed a vaudeville act and adopted the stage name Ted Healy.

Healy's act was a hit, and he soon expanded his role as a comedian and master of ceremonies. In the 1920s, he was the highest-paid performer in vaudeville, making $9000 a week. He added performers to his stage show, including his new wife Betty Brown (a.k.a. Betty Braun), and his German Shepherd dog.[3]

When some of his acrobats quit in 1922, Moe Howard answered the advertisement for replacements. Since Howard was not an acrobat, Healy cast his old friend as a stooge (a purported member of the audience who is picked, ostensibly at random, to come onstage). In the routine, Howard's appearance would end with Healy losing his trousers.

The Stooges

Howard's brother Shemp joined the act as a heckler in 1923, and Larry Fine was added in 1928. Healy's vaudeville revues (A Night in Venice, A Night in Spain, New Yorker Nights, and others) included the quartet under various names, such as Ted Healy and his Southern Gentlemen.

Moe Howard took a break from show business in July 1925 after his marriage to Helen. The group of Moe, Larry & Shemp first became the legendary trio in February 1929 and appeared in the Shuberts' Broadway revue A NIGHT IN VENICE from April 1929 to March 1930, leading to their appearance in the 1930 film Soup to Nuts (filmed in June 1930). In late August 1930 the Stooges and Healy parted ways after a dispute over a movie contract. They began performing on their own, using such monikers as "The Three Lost Souls" and "Howard, Fine and Howard", and often incorporated material from previous Healy shows. Healy attempted to sue the Stooges for using his material, but the copyright was held by the Shubert Theatre Corporation, for which the routines had been produced, and the Stooges had the Shuberts' permission to use it.

Healy hired replacement stooges, consisting of Eddie Moran (soon replaced by Richard "Dick" Hakins), Jack Wolf (father of sportscaster Warner Wolf), and Paul "Mousie" Garner in early 1931. This group appeared in two Broadway plays, with Healy costarring in "The Gang's All Here" and "Billy Rose's Crazy Quilt." The original Stooges rejoined Healy's act in July 1932, but Shemp left on August 19 to pursue a solo career and was replaced by his younger brother Curly Howard. In early 1934, Fine and the Howards permanently parted ways with Healy.

After the Stooges

Healy appeared in a succession of films for MGM from 1934 - 1937, and was also loaned to 20th Century Fox and Warner Brothers for films by those companies, playing both dramatic and comedic roles. One of his films, Mad Holiday (1936), featured stooge Dick Hakins as his sidekick. In San Francisco (1936), a new lineup of "stooges" consisting of Jimmy Brewster, Red Pearson, and Sammy Glasser (aka Sammy Wolfe) filmed a scene with Healy but it was omitted from the final release; a couple of production stills of them exist. Also, in the Technicolor short subject La Fiesta de Santa Barbara (1935), Jimmy Brewster briefly appears to 'stooge' with Healy. During this period Healy took to wearing a toupée in public.[2] His last film, Hollywood Hotel (1937), was released a few days after he died.

Personal life

Healy's first wife was dancer and singer Betty Brown (born Elizabeth Braun), whom he married in 1922[4] one week after they met.[5] The couple worked together in vaudeville, then divorced in 1932[6] after Brown sued heiress Mary Brown Warburton for "alienation of her husband's affections".[7]

Healy's second marriage was to UCLA coed Betty Hickman. After introducing himself, Healy proposed immediately, and the couple became engaged the following day.[8] They were married in Yuma, Arizona on May 15, 1936 after a midnight elopement by plane.[9] Hickman was granted a divorce on October 7, 1936, which was nullified after a reconciliation.[10] Their son, John Jacob, was born on December 17, 1937, four days before Healy's death.[11]

Death

Healy died on December 21, 1937 at the age of 41, after an evening of celebration at the Trocadero nightclub on the Sunset Strip in Los Angeles. He was reportedly celebrating the birth of his son, an event he had eagerly anticipated, according to Moe Howard. "He was nuts about kids," wrote Howard. "He used to visit our homes and envied the fact that we were all married and had children. Healy always loved kids and often gave Christmas parties for underprivileged youngsters and spent hundreds of dollars on toys."[2]

The circumstances surrounding his death remain a matter of some controversy.[12] An MGM spokesman initially announced the cause as a heart attack,[13][14] but the presence of recent wounds—a cut over his right eye and a "discolored" left eye—combined with reports of an altercation at the Trocadero gave rise to speculation that he died as a result of those injuries.[13]

Healy's friend, the writer Henry Taylor, told Moe Howard that the fight was preceded by an argument between Healy and three men whom he identified as "college fellows".[15] The younger men allegedly knocked Healy to the ground and kicked him in the head, ribs and abdomen. The wrestler Man Mountain Dean reported that he was standing in front of the Plaza Hotel in Hollywood at 2:30am when Healy emerged, bleeding, from a taxi. He related an "incoherent story" of being attacked at the Trocadero, but could not identify his assailant.[16] Dean contacted a physician, Sydney Weinberg, who treated Healy at the hotel.[13] Another friend, Joe Frisco, then drove him to his home.[17] Wyantt LaMont, Healy's personal physician, was summoned to the home the following morning when Healy began experiencing convulsions.[1] Despite the efforts of LaMont and a cardiologist, John Ruddock, Healy died later that day. Because of the circumstances, LaMont refused to sign Healy's death certificate.[13]

A later source alleged that the three assailants were not college boys, but actor Wallace Beery, producer Albert R. Broccoli, and Broccoli's cousin, agent/producer Pat DiCicco.[18] While there is no documentation in contemporaneous news reports that either Beery or DiCicco was present, Broccoli admitted that he was indeed involved in a fist fight with Healy at the Trocadero.[19] He later modified his story, stating that a heavily intoxicated Healy had picked a fight with him, the two had briefly scuffled, then shook hands and parted ways.[1] In other reports, Broccoli admitted to pushing Healy, but not striking him.[20]

Following an autopsy, the Los Angeles county coroner reported that Healy died of acute toxic nephritis secondary to acute and chronic alcoholism. Police closed their investigation, as there was no indication in the report that his death was caused by physical assault.[20]

Healy was a prolific spender; despite a weekly salary of $1,700 (equivalent to $28,030 in 2015) he died in debt.[1] He indulged in numerous personal luxuries, and paid his assistant performers' salaries out of his own pocket. He was also financially generous to friends when they were out of work; for example, Frisco, while unemployed, lived at an expensive hotel on Healy's tab.[1] Betty was left responsible for a multitude of liabilities, including hospital bills related to the birth of her son and Healy's medical care.[21] She remained hospitalized for some time after Healy died, leaving their house unattended; as a result, it was robbed of everything of value.[1] A trust fund was organized by friends and colleagues to provide financial support for Betty and her child. A fundraiser was also held, including a $10-per-plate dinner and an auction of the Hollywood Hotel's ledger with hundreds of famous signatures; but Betty later asserted that she had never received any proceeds from the fundraiser.[1]

Ted Healy is interred at Calvary Cemetery in Los Angeles, California, along with his mother and sister.

Legacy

In the decades that followed, many comedy stars, including Milton Berle, Bob Hope, and Red Skelton, cited Healy as a "mentor", and a significant influence on their careers.[22] "Back in [19]25, Ted Healy took me aside and gave me some wonderful advice," Berle told American newspaper and radio gossip commentator Walter Winchell in 1955. "'Milton, always play to the public. Never mind playing to the theatrical crowd. Don't try to impress the trumpet player in the pit. Entertain the people and you'll get rich and famous.' "[23] A caricature of Healy, drawn by Alex Gard, was the first of several hundred hung at Sardi's restaurant in the New York City Theater District.[24]

Filmography

| Year | Title | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1926 | Wise Guys Prefer Brunettes | Napoleon Fizz | Short film |

| 1930 | Soup to Nuts | Ted "Teddy" | |

| 1931 | A Night in Venice | Short film | |

| 1933 | Nertsery Rhymes | Papa | Short film Story |

| 1933 | Stop, Sadie, Stop | Ted | Short film. A lost film |

| 1933 | Beer and Pretzels | Ted Healy | Short film Writer |

| 1933 | Hello Pop! | Father | Short film Writer |

| 1933 | Stage Mother | Ralph Martin | |

| 1933 | Bombshell | Junior Burns | |

| 1933 | Plane Nuts | Ted Healy | Short film Writer |

| 1933 | Meet the Baron | Head Janitor | |

| 1933 | Dancing Lady | Steve - Patch's Assistant | |

| 1933 | Myrt and Marge | Mullins | |

| 1934 | Fugitive Lovers | Hector Withington, Jr. | |

| 1934 | Lazy River | William "Gabby" Stone | |

| 1934 | The Big Idea | Ted Healy, Scenario Company President | Short film Writer |

| 1934 | Hollywood Party | Reporter | Uncredited; last film with the Stooges |

| 1934 | Operator 13 | Doctor Hitchcock | |

| 1934 | Paris Interlude | Jimmy | |

| 1934 | Death on the Diamond | Terry "Crawfish" O'Toole | |

| 1934 | The Band Plays On | Joe | |

| 1934 | Forsaking All Others | Scenes deleted | |

| 1935 | The Winning Ticket | Eddie Dugan | |

| 1935 | The Casino Murder Case | Sergeant Heath | |

| 1935 | Reckless | Smiley | |

| 1935 | Murder in the Fleet | Gabby O'Neill | |

| 1935 | La Fiesta de Santa Barbara | Himself | Color short film |

| 1935 | Mad Love | Reagan | |

| 1935 | Here Comes the Band | Happy | |

| 1935 | It's in the Air | Clip McGurk | |

| 1936 | Speed | Clarence Maxmillian "Gadget" Haggerty | |

| 1936 | San Francisco | Mat | |

| 1936 | Sing, Baby, Sing | Al Craven | |

| 1936 | The Longest Night | Police Sergeant Magee | |

| 1936 | Mad Holiday | Mert Morgan | |

| 1937 | Man of the People | Joe The Glut | |

| 1937 | The Good Old Soak | Al Simmons | |

| 1937 | Varsity Show | William Williams | |

| 1937 | Hollywood Hotel | Fuzzy Boyle | |

| 1938 | Love Is a Headache | Jimmy Slattery | |

| 1938 | Of Human Hearts | Uncredited | |

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Cassara, Bill (2014). Nobody's Stooge: Ted Healy. BearManor Media. ISBN 1593937687.

- 1 2 3 Maurer, Joan Howard; Jeff Lenburg; Greg Lenburg (2012). The Three Stooges Scrapbook. Chicago, Illinois: Chicago Review Press. pp. 2–9. ISBN 978-1-6137-4074-3.

- ↑ staff (September 30, 1924). "Princess Bill is Rich in Comedy". The Montreal Gazette. Retrieved 27 August 2015.

- ↑ "Mrs. Ted Healy Seeks Decree". Rochester Evening Journal. January 27, 1932. p. 4. Retrieved May 15, 2013.

- ↑ staff (May 11, 1925). "Betty Healy's Fairy Tale Rivals Cinderella Legend". The Pittsburgh Press. Retrieved 27 August 2015.

- ↑ staff (May 14, 1936). "California Girl Bride of Healy Comedian". Reading Eagle. Retrieved 27 August 2015.

- ↑ staff (January 28, 1932). "Comedian's Wife Suing Heiress". The Milwaukee Journal. Retrieved 27 August 2015.

- ↑ Garner, Paul; Kissane, Sharon (January 1999). Mousie Garner: autobiography of a vaudeville stooge. Mcfarland & Co Inc. p. 72. ISBN 978-0-7864-0581-7. Retrieved August 27, 2015.

- ↑ staff (May 15, 1936). "Ted Healy Wed After Elopement by Plane". The Evening Independent. Retrieved 27 August 2015.

- ↑ staff (October 8, 1936). "Ted Healy's Wife Granted Divorce". The Milwaukee Sentinel. Retrieved 27 August 2015.

- ↑ "Dead Comedian's Son 10 Days Old". Spokane Daily Chronicle. December 29, 1937. p. 21. Retrieved May 15, 2013.

- ↑ "Ted Healy Dies. Autopsy Ordered. Rumors of Cafe Fight Add Some Mystery to Passing of Actor in California Home". New York Times. December 22, 1937. Retrieved 11 July 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 "Police Probe Death of Ted Healy, Motion Picture Star". The Evening Independent. December 22, 1937. p. 1. Retrieved May 15, 2013.

- ↑ staff (December 22, 1937). "Police Drop Healy Probe". Prescott Evening Courier. p. 1. Retrieved May 15, 2013.

- ↑ Maurer, Joan Howard; Jeff Lenburg; Greg Lenburg (2012). The Three Stooges Scrapbook. Chicago, Illinois: Chicago Review Press. p. 8. ISBN 978-1-6137-4074-3.

- ↑ staff (December 22, 1937). "Foul Play Ruled Out In Ted Healy's Death". The Pittsburgh Press. p. 2. Retrieved May 15, 2013.

- ↑ Howard, Moe; Howard Maurer, Joan (2013). I Stooged to Conquer: The Autobiography of the Leader of the Three Stooges. Chicago Review Press. p. 42. ISBN 978-1-6137-4766-7.

- ↑ Fleming, E.J. (2004). The Fixers: Eddie Mannix, Howard Strickling, and the MGM Publicity Machine. McFarland. pp. 174–177. ISBN 978-0-7864-2027-8.

- ↑ staff (December 23, 1937). "Wealthy Sportsman Confesses Fight with Ted Healy". The Oxnard Daily Courier. p. 1. Retrieved May 15, 2013.

- 1 2 "Ted Healy Died of Toxic Nephritis". Lewiston Evening Journal. December 23, 1937. p. 8. Retrieved May 15, 2013.

- ↑ Cullen, Frank (October 9, 2006). Vaudeville, Old and New: An Encyclopedia of Variety Performers in America. 1. Routledge. p. 495. ISBN 978-0415938532.

- ↑ Braund, Simon (2012). "The Tragic And Twisted Tale Of The Three Stooges". EmpireOnline. Retrieved 1 September 2015.

- ↑ Winchell, Walter (September 17, 1955). "Editorial". The Daytona Beach News-Journal. p. 4. Retrieved 1 September 2015.

- ↑ "Inventory of Sardi's Caricatures". The New York Public Library. Retrieved 1 September 2015.

Further reading

- The Complete Three Stooges: The Official Filmography and Three Stooges Companion by Jon Solomon, (Comedy III Productions, Inc., 2002).

- The Three Stooges Scrapbook by Jeff Lenburg, Joan Howard Maurer, Greg Lenburg (Citadel Press, 1994).

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ted Healy. |

- Ted Healy and his Stooges vaudeville routine from Plane Nuts

- Ted Healy at the Internet Movie Database

- Ted Healy at the Internet Broadway Database

- Ted Healy at Find a Grave

- Digging though the Hollywood archives