Ten suchnesses

| Part of a series on |

| Mahāyāna Buddhism |

|---|

|

|

Teachings |

|

Mahāyāna schools |

|

|

The Ten suchnesses (Chinese: 十如是 shí rúshì; Japanese: 十如是 jū nyoze) are a Mahayana doctrine which is important, as well as unique, to that of the Tiantai (Tendai) and Nichiren Buddhist schools of thought. The doctrine is derived from a passage found within the second chapter of Kumarajivas Chinese translation of the Lotus Sutra, that "characterizes the ultimate reality (literally, “real mark”) of all dharmas in terms of ten suchnesses."[1] This concept is also known as the ten reality aspects, ten factors of life, or the Reality of all Existence.[2][3][4]

Origin

The list of ten suchnesses is neither found in Dharmarakshas Chinese translation nor in the Tibetan edition or any of the extant Sanskrit manuscripts.[5][6][7]

The Sanskrit editions of the Lotus Sutra list only five elements:[7][note 1]

Only the Thus Come One knows all the dharmas:what are the dharmas, how are the dharmas, what are the dharmas like, of what characteristics are the dharmas, of what nature are the dharmas; what they are, how they are, what they are like, of what characteristics they are, of what nature are the dharmas, only the Thus Come One has had direct experience in those dharmas.[10][11]

Kumarajiva translates the passage in chapter two as:[note 2]

Only a Buddha and a Buddha can exhaust their reality, namely the suchness of the dharmas, the suchness of their marks, the suchness of their nature, the suchness of their substance, the suchness of their powers, the suchness of their functions, the suchness of their causes, the suchness of their conditions, the suchness of their effects, the suchness of their retributions, and the absolute identity of their beginning and end.[15]

The discrepancy between Kumarajivas translation and the Sanskrit editions might be due to Kumarajivas use of a manuscript variant but Groner and Stone suggest that "the expansion of this list to ten is probably Kumarajlvas invention and may well be presaged in a passage in the Dazhidulun that includes nine aspects."[16][10][note 3]

Definitions

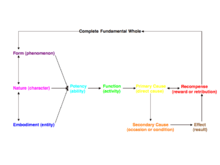

The following definitions are given by the Soka Gakkai English Buddhist Dictionary Committee[19] and describe what each suchness means in more detail:

- Appearance (form): the attributes of everything that is discernible, such as color, shape, or behavior.

- Nature (nature): the inherent disposition or quality of a person or thing that cannot be discerned from the outward appearance.

- Entity (embodiment): the substance of life that permeates as well as integrates both appearance and nature.

The above three suchnesses describe the reality of life itself. The next six suchnesses, from the fourth through the ninth, explain the functions and workings of life.

- Power (potency): life's potential energy.

- Influence (function): the activity produced when life's inherent power or potential energy is activated.

- Internal cause (primary cause): the potential cause in life that produces an effect of the same quality as itself, i.e., good, evil, or neutral.

- Relation (secondary Cause): the relationship of secondary, indirect causes to the internal cause. Secondary causes are various conditions, both internal and external, that help the internal cause produce an effect.

- Latent effect (effect): the dormant effect produced in life when an internal cause is activated through its related conditions.

- Manifest effect (recompense): the tangible, perceivable effect that emerges in time as an expression of a dormant effect and therefore of a potential cause, again through its related conditions.

- Consistency from beginning to end (complete fundamental whole): the unifying factor among the ten suchnesses. It indicates that all of the other nine suchnesses from Appearance to Manifest Effect are consistently interrelated. All nine suchnesses thus harmoniously express the same condition of existence at any given moment.

Interpretation

The ten suchnesses, or categories, are what led the sixth century Chinese Buddhist philosopher Zhiyi to establish the doctrine of the "three thousand [worlds] in one thought."[4] The Tiantai school describes ten dharma realms (ch. shi fajie) of sentient beings, the realms of hell dwellers, hungry ghosts, beasts, asuras, humans, gods (devas), sravakas, pratyekabuddhas, bodhisattvas and Buddhas.[20][21] According to Zhiyi, each of these ten dharma realms mutually includes all of the other realms, resulting in 100 "states of existence" that share the characteristics of the ten suchnesses.[22] The one thousand suchnesses are active in each of the three spheres (the five skandhas, sentient beings,and their environment) forming three thousand worlds in one thought moment.[23][24]

Nichiren regarded the doctrine of "three thousand [worlds] in one thought" (ichinen-sanzen) as the very essence of the Buddha's teachings.[25] He wrote in his work Kaimoku-shō (Essay on the Eye-opener) concerning ichinen-sanzen: "The very doctrine of the Three Thousand Realms in One Mind of the Tendai sect appears to be the way to lead man to buddhahood."[25]

Nikkyo Niwano states that the principle of the Reality of All Existence not only analyzes what modern science would analyze in physical substances to the extent of subatomic particles, but also extends to mental state.[26] Accordingly, everyone's mind has existing within it the ten realms of existence which are said to be found within one another.[27] The suchnesses reveal the deepest reality inherent within all things, and, consequently, innumerable embodied substances existing in the universe are interrelated with all things. The suchnesses, one through nine, operate according to the law of the universal truth, namely from the "complete fundamental whole" under which no one, no thing, and no function can depart. All things, including man, along with their relations with everything else are formed from the Reality of All Existence that is the Ten Suchnesses.[28]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Similar translations of this passage in Sanskrit manuscripts were published by Kern and Burnouf.[8][9]

- ↑ For alternative English translations of Kumarajivas text, see Kato, Kubo and Watson.[12][13][14]

- ↑ The Great Perfection of Wisdom Treatise (Chinese Dazhidu lun, Japanese Daichido ron), a work traditionally attributed to Nagarjuna, translated by Kumarajiva in 406 CE (T 25.298c). It contains a broad commentary on the Pancavimsatisahasrikaprajnaparamitasutra and Buswell describes it as an "authoritative source" of Mahayana doctrine for Chinese scholars like Sengzhao, Fazang, Zhiyi and Tanluan.[17][18]

References

- ↑ Buswell 2004, p. 845.

- ↑ Reeves 2008, p. 425

- ↑ Soka Gakkai English Buddhist Dictionary Committee 2002

- 1 2 Kato 1993, p. 52

- ↑ Robert 2011, pp. 148-153.

- ↑ Pye 2003, pp. 20-21.

- 1 2 Groner 2014, p. 7.

- ↑ Kern 1884, p. 32.

- ↑ Burnouf 1925, p. 20.

- 1 2 Robert 2011, p. 148.

- ↑ Wogihara 1934, p. 20.

- ↑ Kato 1975, p. 31.

- ↑ Kubo 2007, p. 23.

- ↑ Watson 2009, p. 57.

- ↑ Hurvitz 1976, pp. 22-23.

- ↑ Groner 2014, p. 7-8.

- ↑ Buswell 2013, p. 227.

- ↑ Lamotte 1944.

- ↑ Soka Gakkai English Buddhist Dictionary Committee (2002)

- ↑ Buswell 2013, p. 804.

- ↑ Pocezki 2014, p. 168.

- ↑ Swanson 1989, pp. 11-12.

- ↑ Gregory 2002, pp. 410-411, 437.

- ↑ Buswell 2013, p. 1029.

- 1 2 Niwano 1976, p. 109

- ↑ Niwano 1976, p. 111

- ↑ Niwano 1976, p. 110

- ↑ Niwano 1976, p. 112

References

- Burnouf, Eugène (tr.) (1925). Le Lotus de la Bonne Loi : Traduit du sanskrit, accompagné d'un commentaire et de vingt et un mémoires relatifs au Bouddhisme, tome 1. Paris: Maisonneuve

- Buswell, Robert E., ed. (2004). "Tiantai School", in Encyclopedia of Buddhism. Macmillan Reference USA. p. 845. ISBN 0-02-865718-7.

- Buswell, Robert Jr; Lopez, Donald S. Jr., eds. (2013). Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691157863.

- Groner, Paul; Stone, Jacqueline I. (2014). "Editors' Introduction: The "Lotus Sutra" in Japan". Japanese Journal of Religious Studies. 41 (1): 1–23. Archived from the original on June 14, 2014.

- Hurvitz, Leon (tr.) (1976). Scripture of the Lotus Blossom of the Fine Dharma: The Lotus Sutra. New York: Columbia University Press

- Kato, Bunno; Tamura, Yoshirō; Miyasaka, Kōjirō, trans. (1975). The Threefold Lotus Sutra: The Sutra of Innumerable Meanings; The Sutra of the Lotus Flower of the Wonderful Law; The Sutra of Meditation on the Bodhisattva Universal Virtue (PDF). New York/Tōkyō: Weatherhill & Kōsei Publishing. p. 31.

- Kubo, Tsugunari; Yuyama, Akira, trans. (2007). The Lotus Sutra (PDF). Berkeley, Calif.: Numata Center for Buddhist Translation and Research. p. 23. ISBN 978-1-886439-39-9.

- Lamotte, Etienne (trans.); Nāgārjuna; Kumārajīva (1944). Le traité de la grande vertu de sagesse de Nāgārjuna (Mahāprajñāpāramitāśāstra). Louvain: Bureaux du Muséon

- Niwano, Nikkyo (1976), Buddhism For Today: A Modern Interpretation of the Threefold Lotus Sutra (PDF), Tōkyō: Kōsei Publishing Co., ISBN 4-333-00270-2, archived from the original (PDF) on July 22, 2013

- Pye, Michael (2003). Skilful Means - A concept in Mahayana Buddhism. Routledge. ISBN 0203503791.

- Reeves, Gene (2008). The Lotus Sutra: A Contemporary Translation of a Buddhist Classic. Somerville: Wisdom Publications. ISBN 0-86171-571-3.

- Soka Gakkai English Buddhist Dictionary Committee (2002). "Ten factors of life", in The Soka Gakkai Dictionary of Buddhism. Tōkyō: Soka Gakkai. ISBN 978-4-412-01205-9.

- Robert, Jean-Noel (2011). "On a Possible Origin of the " Ten Suchnesses " List in Kumārajīva's Translation of the Lotus Sutra". Journal of the International College for Postgraduate Buddhist Studies. 15: 54–72.

- Swanson, Paul Loren (1989). Foundations of Tʻien-Tʻai Philosophy: The Flowering of the Two-truth Theory in Chinese Buddhism. Jain Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-89581-919-2.

- Watson, Burton (tr.) (2009). The Lotus Sutra and Its Opening and Closing Sutras. Tokyo: Soka Gakkai .ISBN 978-4-412-01409-1; p. 57

- Wogihara, U.; Tsuchida, C. (1934). Saddharmapundarīka-sūtram: Romanized and Revised Text of the Bibliotheca Buddhica Publication, Tokyo: The Sankibo Buddhist Book Store

External links

- 10 suchnesses in Rissho Kosei-kai Teachings

- Hsuan Hua, The Dharma Flower Sutra, A Commentary by the Venerable Master Hsuan Hua, chapter 2, Buddhist Text Translation Society