Terle Sportplane

| Terle Sportplane | |

|---|---|

| |

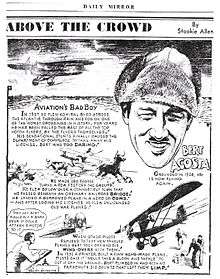

| Joseph Terleph congratulates test pilot Burt Acosta on a successful first flight in the JT1. Taken Roosevelt Field, Long Island | |

| Role | Sport aircraft |

| National origin | United States of America |

| Designer | Joseph Terle (Joe Terleph) |

| First flight | May 1931 |

| Number built | 1 |

| Unit cost |

$1200 in 1931 |

The Terle Sportplane was an original homebuilt design built by Joseph Terle, who had no prior aircraft design experience.[1]

Design and development

The aircraft was developed from aviation articles and magazines between 1929 and 1931. The airfoil was copied from the Spirit of St. Louis profile.[1]

The Terle Sportplane is an all wood parasol taildragger powered by a Salmson radial. After an accident with the prototype, the fuselage was changed to welded steel tube with aircraft fabric covering.

Operational history

The Sportplane was tested at Roosevelt Field in New York in 1931, but the CAA did not register it as a licensed aircraft. The aircraft was later test flown by the famous test pilot, Bert Acosta, who found it perfect for his use since he was currently grounded from flying licensed aircraft by a previous infraction. After performing aerobatics with the aircraft before a large crowd, Acosta and Terle planned to produce the aircraft together as the "Acosterle Wildcat". The aircraft was test flown for two years, but could not meet certification requirements.[2] The JT1 developed 40HP at 1800RPM and 52HP at 2200RPM.

Notes on Joseph Terle and the Construction of the JT1

In 1931 to build an airplane in one’s garage was no ordinary feat. When Joseph Terleph (he used the easier name "Terle" for business purposes) who had not yet flown a plane took his completed craft to Roosevelt Field on Long Island to see if it could at least be taxied, and then had it taken aloft by a famous if reckless barnstorming pilot to be rigorously and successfully tested and found airworthy, it proved to be at the time, not only unusual, but sensational.

Joseph Terleph (1900–82) was one of those technically gifted people, who as was the case for many in previous generations, had his education cut short by lack of opportunity and bad luck. He was the oldest of seven siblings, and when he was fifteen, his father died and the main support of the family devolved upon him. His formal education necessarily ended with grade school, though he later took high school courses at night and later subscribed to three years of correspondence courses in mechanical engineering.

Joe obtained a first grade commercial radio operator’s license in his mid-teens, and on the strength of that he was allowed to enlist in the Navy at the age of eighteen with the rank of a second-class petty officer at the tail end of World War I. He was in the Navy only for a short time before the war ended, but he then parlayed his radio credentials into becoming the radio officer on merchant ships for two years. Leaving the sea, he taught himself the craft of printing and founded his own business, which he kept going until along with many other businesses at the time, it succumbed to the ravages of the great depression. Despite the loss of his business, during the whole of the depression he managed to work as a printer in a plant maintained by a department store for its own advertising, so that he and his family did not have to endure the kind of privations that he had experienced in his youth.

In the 1920s the country was wild about aeronautics and the exploits of the many daring pilots of those times. This was brought to a highpoint with Charles Lindbergh’s successful solo flight across the Atlantic in 1927. It was around this time that Joe, lacking the necessary social and financial resources, not long married and with a young daughter, but having faith in his own mechanical talent, decided to build his own plane. At the time he was living in a rented house in Queens County New York. As he described it in his autobiographical notes, one night after work in the printing plant, he was relaxing reading a magazine when he came upon an ad for a book called "The Sport Plane Constructor." The price was $1, and the "book" consisted of 32 pages with crudely executed drawings. As an extra, the author offered to sell a jig, or wooden form for holding the various pieces of a wing rib for gluing and nailing. With it, the uniformly sized ribs would be ready for mounting on the wing spars, so Joe bought the jig as well.

Since the wing and fuselage were made of wood, Joe also discovered he would need both a circular and jig saw to fabricate the various pieces, so he bought those too. Next, telling his wife he needed a wood turning lathe to "build furniture," he purchased that as well. He was then on his way, the project taking shape in his garage after work and on weekends.

Joe went on to purchase additional material as necessary for the plane’s construction from a business called Air Associates located at Roosevelt Field farther out on Long Island. As he described in his notes, he made the wooden members of the fuselage by hand, using a vice, and also drilled the holes for the wires by hand. In general almost all the parts of the plane (excluding the engine of course) he made by hand, despite his not having previously worked as a machinist or with machine tools. The engine was a nine-cylinder air cooled radial Salmson made in France that weighed 165 pounds and came with a propeller. The propeller was too long for the design of the plane so he had to have it shortened.

Joe built the wing in two sections and bolted them together in the center. Their total length came to 28ꞌ7ꞌꞌ and a width of 4ꞌ2ꞌꞌ. He covered the joined wings with nine pieces of unbleached muslin 3 x 8.5 feet, and sewed them together with an ordinary domestic sewing machine borrowed from his wife (who by this time recognized she was not going to come into possession of any handcrafted furniture). He sewed the fabric to each rib and the trailing edge by hand. He then covered it with 2 ½ inches of scalloped tape and painted the fabric with two coats of acetate dope. He followed this with three coats of nitrate dope— orange for the wings and black for the fuselage. He fashioned 28 ribs, each constructed of 16 pieces of ¼ inch spruce strips and 36 gussets of 1/16 inch plywood glued and nailed and requiring 250 brads for each rib.

During the assembly Joe held the various pieces in the jig, slid the ribs onto spars for each wing section, and braced them with piano wire that he tightened with turnbuckles. The leading-edge was a piece of spruce, shaped to conform to the front and of the ribs and the trailing edge of the wing consisted of a length of ¼ inch steel tubing. He then welded the wing struts and the landing gear in place.

To mount the wing precisely in the correct position for the plane’s balance he placed a 170-pound weight in the cockpit to substitute for a pilot, and the tanks filled with gas and oil. He then placed the fuselage on pivots until it balanced perfectly. The center of that particular airfoil design, called the "Clark Y," was 30% back from the leading-edge, and it was there that he bolted the wings to the supporting struts. He fashioned the engine cowling from a soft sheet of aluminum that he hammered into shape with a rawhide mallet on a bag filled with sand.

When after two years his project was finished, Joe tied the wing sections to the roof of his car and attached the tail skid of the fuselage to the rear bumper. He then towed the plane backward on its wheels to Roosevelt field in Garden City, 12 miles from his home.

What happened next is perhaps best described in an article in the New York Herald Tribune of Monday, May 11, 1931. (Disregard three errors – it took Joe two years to build, not ten, the engine was a Salmson not a Sampson, and Joe was 31 years old, not 29).

Specifications (Terle Sportplane)

Data from Experimenter

General characteristics

- Capacity: 1

- Length: 16 ft (4.9 m)

- Wingspan: 29 ft (8.8 m)

- Height: 6 ft (1.8 m)

- Wing area: 122 sq ft (11.3 m2)

- Empty weight: 450 lb (204 kg)

- Fuel capacity: 10 gal (38 litres)

- Powerplant: 1 × Salmson 9 AD Radial, 40 hp (30 kW)

Performance

- Maximum speed: 87 kn; 161 km/h (100 mph)

- Cruise speed: 61 kn; 113 km/h (70 mph)

- Stall speed: 26 kn; 48 km/h (30 mph)

References

- "Acosta Stunts Hour in Plane Built by Novice". New York Herald-Tribune. May 11, 1931.

- McRoe, Jack (May 1957). "The Terle Sportplane". The Experimenter Magazine.