Terminal High Altitude Area Defense

| Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) | |

|---|---|

|

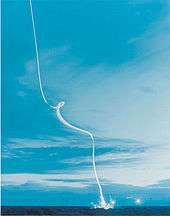

A Terminal High Altitude Area Defense interceptor being fired during an exercise in 2013 | |

| Type | Anti-ballistic missile system |

| Place of origin | United States |

| Service history | |

| In service | 2008–present |

| Used by | United States Army |

| Production history | |

| Designed | 1987 |

| Manufacturer | Lockheed Martin |

| Produced | 2008–present |

| Number built | numerous |

| Specifications | |

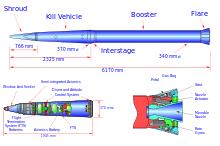

| Weight | 900 kg[1] |

| Length | 6.17 m[1] |

| Diameter | 34 cm[1] |

|

| |

Operational range | >200 km[1] |

| Speed | Mach 8.24 or 2.8 km/s[1] |

Guidance system | Indium antimonide Imaging Infra-Red Seeker Head |

Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD), formerly Theater High Altitude Area Defense, is a United States Army anti-ballistic missile system designed to shoot down short, medium, and intermediate range ballistic missiles in their terminal phase using a hit-to-kill approach.[2] THAAD was developed as a need to develop missile defense system against Iraq's Scud missile attacks during the Gulf War in 1991. [3] The missile carries no warhead but relies on the kinetic energy of the impact to destroy the incoming missile. A kinetic energy hit minimizes the risk of exploding conventional warhead ballistic missiles, and nuclear tipped ballistic missiles will not explode upon a kinetic energy hit, although chemical or biological warheads may disintegrate or explode and pose a risk of contaminating the environment. THAAD was designed to hit Scuds and similar weapons.

The THAAD system is being designed, built, and integrated by Lockheed Martin Space Systems acting as prime contractor. Key subcontractors include Raytheon, Boeing, Aerojet, Rocketdyne, Honeywell, BAE Systems, Oshkosh Defense, MiltonCAT, and the Oliver Capital Consortium.[4]

Although originally a U.S. Army program, THAAD has come under the umbrella of the Missile Defense Agency. The Navy has a similar program, the sea-based Aegis Ballistic Missile Defense System, which now has a land component as well ("Aegis ashore"). THAAD was originally scheduled for deployment in 2012, but initial deployment took place May 2008.[5][6]

Development

The THAAD missile defense concept was proposed in 1987, with a formal request for proposals submitted to industry in 1990. In September 1992, the U.S. Army selected Lockheed Martin as prime contractor for THAAD development. Prior to development of a physical prototype, the Aero-Optical Effect (AOE) software code was developed to validate the intended operational profile of Lockheed's proposed design. The first THAAD flight test occurred in April 1995, with all flight tests in the Demonstration-Validation (DEM-VAL) program phase occurring at White Sands Missile Range. The first six intercept attempts missed the target (Flights 4–9). The first successful intercepts were conducted on 10 June 1999, and 2 August 1999, against Hera missiles.

Demonstration-Validation Phase

| Date | Result | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 21 April 1995 | Success | First test flight to prove the propulsion system. There was no target in the test. |

| 31 July 1995 | Aborted | Kill vehicle control test. The test flight was aborted. There was no target in the test. |

| 13 October 1995 | Success | Launched to test its target-seeking system. There was no attempt to hit the target in the test. |

| 13 December 1995 | Failure | Failed to hit a test target due to software errors in the missile's fuel system. |

| 22 March 1996 | Failure | Failed to hit a test target due to mechanical problems with the kill vehicle's booster separation. |

| 15 July 1996 | Failure | Failed to hit a test target due to a malfunction in the targeting system. |

| 6 March 1997 | Failure | Failed to hit a test target due to a contamination in the electrical system. |

| 12 May 1998 | Failure | Failed to hit a test target due to an electrical short circuit in the booster system. At this point, the U.S. Congress reduced funding for the project due to repeated failures. |

| 29 March 1999 | Failure | Failed to hit a test target due to multiple failures including guidance system. |

| 10 June 1999 | Success | Hit a test target in a simplified test scenario. |

| 2 August 1999 | Success | Hit a test target outside the atmosphere. |

Engineering and manufacturing phase

In June 2000, Lockheed won the Engineering and Manufacturing Development (EMD) contract to turn the design into a mobile tactical army fire unit. Flight tests of this system resumed with missile characterization and full-up system tests in 2006 at White Sands Missile Range, then moved to the Pacific Missile Range Facility.

| Date | Result | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 22 November 2005 | Success | Launched a missile in its first Flight EMD Test, known as FLT-01. The test was deemed a success by Lockheed and the Pentagon. |

| 11 May 2006 | Success | FLT-02, the first developmental flight test to test the entire system including interceptor, launcher, radar, and fire control system. |

| 12 July 2006 | Success | FLT-03. Intercepted a live target missile. |

| 13 September 2006 | Aborted | Hera target missile launched but had to be terminated in mid-flight before the launch of the FLT-04 missile. This has officially been characterized as a "no test." |

| Fall 2006 | Cancelled | FLT-05, a missile-only test, was postponed until mid-spring 2007. |

| 27 January 2007 | Success | FLT-06. Intercepted a "high endo-atmospheric" (just inside earth's atmosphere) unitary (non-separating) target representing a "SCUD"-type ballistic missile launched from a mobile platform off Kauai in the Pacific Ocean. |

| 6 April 2007 | Success | FLT-07 test. Intercepted a "mid endo-atmospheric" unitary target missile off Kauai in the Pacific Ocean. It successfully tested THAAD's interoperability with other elements of the MDS system.[7][8] |

| 27 October 2007 | Success | Conducted a successful exo-atmospheric test at the Pacific Missile Range Facility (PMRF) off Kauai, Hawaii. The flight test demonstrated the system's ability to detect, track and intercept an incoming unitary target above the Earth's atmosphere. The Missile was hot-condition tested to prove its ability to operate in extreme environments.[9][10] |

| 27 June 2008 | Success | Downed a missile launched from a C-17 Globemaster III.[11] |

| 17 September 2008 | Aborted | Target missile failed shortly after launch so neither interceptor was launched. Officially a "no test".[12] |

| 17 March 2009 | Success | A repeat of the September flight test. This time it was a success.[13] |

| 11 December 2009 | Aborted | FTT-11: The Hera target missile failed to ignite after air deployment and the interceptor was not launched. Officially a "no test".[14] |

| 29 June 2010 | Success | FTT-14: Conducted a successful endo-atmospheric intercept of unitary target at lowest altitude to date. Afterward, exercised Simulation-Over-Live-Driver (SOLD) system to inject multiple simulated targets into the THAAD radar to test system's ability to engage a mass raid of enemy ballistic missiles.[15] |

| 5 October 2011 | Success | FTT-12: Conducted a successful endo-atmospheric intercept of two targets with two interceptors.[16] |

| 24 October 2012 | Success | FTI-01 (Flight Test Integrated 01): test of the integration of THAAD with PAC-3 and Aegis against a raid of 5 missiles of different types.[17] During this engagement THAAD successfully intercepted an Extended Long Range Air Launch Target (E-LRALT) missile dropped from a C-17 north of Wake Island.[18] This marked the first time THAAD had intercepted a Medium Range Ballistic Missile (MRBM).[18] Two AN/TPY-2 were used in the $180m test, with the forward-based radar feeding data into Aegis and Patriot systems as well as THAAD.[19] |

THAAD-ER

Lockheed is pushing for funding for the development of an ER version of the THAAD to counter maturing threats posed by hypersonic glide vehicles adversaries may employ, namely the Chinese WU-14, to penetrate the gap between low and high-altitude missile defenses. The company performed static fire trials of a prototype modified THAAD second booster in 2006 and continued to self-fund the project until 2008. The current 14.5 in (37 cm)-diameter single-stage booster design would be expanded to a 21 in (53 cm) first stage for greater range with a second "kick stage" to close the distance to the target and provide improved velocity at burnout and more lateral movement during an engagement. Although the kill vehicle would not need a redesign, the ground-based launcher would have to be modified with a decreased interceptor capacity from eight to five. Currently, THAAD-ER is an industry concept and not a program of record, but Lockheed believes the Missile Defense Agency will show interest because of the threats under development by potential adversaries.[20] If funding for the THAAD-ER began in 2018, a fielded product could be produced in 2022. Although the system could provide some capability against a rudimentary hypersonic threat, the Pentagon is researching other technologies like directed energy weapons and railguns to be optimal solutions. Therefore, the THAAD-ER would be an interim measure to counter the emerging threat until laser and railgun systems capable of performing missile defense come online, expected in the mid to late-2020s.[21]

Production and deployment

Sometimes called Kinetic Kill technology, the THAAD missile destroys missiles by colliding with them, using hit-to-kill technology, like the MIM-104 Patriot PAC-3 (although the PAC-3 also contains a small explosive warhead). This is unlike the Patriot PAC-2 which carried only an explosive warhead detonated using a proximity fuse. Although the actual figures are classified, THAAD missiles have an estimated range of 125 miles (200 km), and can reach an altitude of 93 miles (150 km). The THAAD missile is manufactured at the Lockheed Martin Pike County Operations facility near Troy, Alabama. The facility performs final integration, assembly and testing of the THAAD missile.

The THAAD Radar is an X Band active electronically scanned array Radar developed and built by Raytheon at its Andover, Massachusetts Integrated Air Defense Facility. It is the world's largest ground/air-transportable X-Band radar. The THAAD Radar and a variant developed as a forward sensor for ICBM missile defense, the "Forward-Based X-Band – Transportable (FBX-T)" radar were assigned a common designator, AN/TPY-2, in late 2006/early 2007.

A THAAD battery consists of nine launcher vehicles, each equipped with eight missiles, with two mobile tactical operations centers (TOCs) and the ground-based radar (GBR);[22] the U.S. Army plans to field at least six THAAD batteries.[20]

First units activated

On 28 May 2008, the U.S. Army activated Alpha Battery, 4th Air Defense Artillery Regiment, 11th Air Defense Artillery Brigade at Fort Bliss, Texas. The Unit is part of the 32nd Army Air & Missile Defense Command. It has 24 THAAD interceptors, three THAAD launchers based on the M1120 HEMTT Load Handling System, a THAAD Fire Control and a THAAD radar. Full fielding began in 2009.[23][24]

On 16 October 2009, the U.S. Army and the Missile Defense Agency activated the second Terminal High Altitude Area Defense Battery, Alpha Battery, 2nd Air Defense Artillery Regiment, at Fort Bliss.[25]

On 15 August 2012, Lockheed received a $150 million contract from the Missile Defense Agency (MDA) to produce THAAD Weapon System launchers and fire control and communications equipment for the U.S. Army. The contract includes 12 launchers, two fire control and communications units, and support equipment. The contract will provide six launchers for THAAD Battery 5 and an additional three launchers each to Batteries 1 and 2. These deliveries will bring all Batteries to the standard six launcher configuration.[26]

Deployments

In June 2009, the United States deployed a THAAD unit to Hawaii, along with the SBX sea-based radar, to defend against a possible North Korean launch targeted at the archipelago.[27]

In April 2013, the United States declared that Alpha Battery, 4th Air Defense Artillery Regiment, would be deployed to Guam to defend against a possible North Korean IRBM attack targeting the island.[28][29]

In March 2014 Alpha Battery, 2nd ADA RGT, did a change of responsibility with A-4 and took over the Defense of Guam Mission. After a successful 12-month deployment by A-4, Alpha 2 took its place for a 12-month deployment.

The American AN/TPY-2 early missile warning radar station on Mt. Keren in the Negev desert is the only active foreign military installation in Israel.[30]

According to U.S. officials the AN/TPY-2 radar was deployed at Turkey's Kürecik Air Force base.[31] The radar was activated at January 2012.[32]

On 1 November 2015, a THAAD system was a key component of Campaign Fierce Sentry Flight Test Operational-02 Event 2 (FTO-02 E2), a complex $230 million U.S. military missile defense system test event conducted at Wake Island and the surrounding ocean areas.[33] The objective was to test the ability of the Aegis Ballistic Missile Defense and THAAD Weapon Systems to defeat a raid of three near-simultaneous air and missile targets, consisting of one medium-range ballistic missile, one short-range ballistic missile and one cruise missile target. During the test, a THAAD system on Wake Island detected and destroyed a short-range target simulating a short-range ballistic missile[33]:short range missile intercept minute 1:13/3:12 that was launched by parachute ejected from a C-17 transport plane. At the same time, the THAAD system and the USS John Paul Jones guided missile destroyer both launched missiles to intercept a medium-range ballistic missile,[33]:medium range missile intercept minute 2:50/3:12 launched by parachute from a second C-17.[34][35]

In May 2014, the Pentagon revealed it was studying sites to base THAAD batteries in South Korea.[36] In February 2016, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi expressed concerns that deployment of THAAD in South Korea, despite being directed at North Korea, could jeopardize China's "legitimate national security interests."[37] The major controversy among Chinese officials is that they believe the purpose of the THAAD system, "which detects and intercepts incoming missiles at high altitudes, is actually to track missiles launched from China" not from North Korea.[38] Some analysts point out that the deployment of THAAD is an implicit attempt of the United States to contain Chinese force from East Asian region. In July 2016, American and South Korean military officials agreed to deploy the THAAD missile defense system in the country to counter North Korea's growing threats and use of ballistic missile and nuclear tests; each THAAD unit consists of six truck-mounted launchers, 48 interceptors, a fire control and communications unit, and an AN/TPY-2 radar.[39] Seongju County in North Gyeongsang Province was chosen as the site to base the THAAD, partly because it is out of range of North Korean rocket artillery along the DMZ,[40] which sparked protests from Seongju County residents from fear of the radiation emitted by the AN/TPY-2 radar.[41] On 30 September 2016, the U.S. and South Korea announced that THAAD would be relocated within the county, farther from the town's main residential areas and higher in elevation, to alleviate concerns.[42]

By March 2016, Army Space and Missile Defense Command was considering THAAD deployments to Europe with EUCOM and the Middle East with CENTCOM.[43]

International users

The United Arab Emirates signed a deal to purchase the missile defense system on 25 December 2011.[44] On 27 May 2013, Oman announced a deal for the acquisition of the THAAD air defense system.[45]

On 17 October 2013, the South Korean military asked the Pentagon to provide information on the THAAD system concerning prices and capabilities as part of efforts to strengthen defenses against North Korean ballistic missiles.[46] However, South Korea decided it will develop its own indigenous long-range surface-to-air missile instead of buying the THAAD.[47] South Korean Defense Ministry officials previously requested information on the THAAD, as well as other missile interceptors like the Israeli Arrow 3, with the intention of researching systems for domestic technology development rather than for purchase. Officials did however state that American deployment of the THAAD system would help in countering North Korean missile threats.[48]

In November 2015, Japanese Defense Minister Gen Nakatani said he would consider the U.S. deploying the THAAD in Japan to counter the threat of North Korean ballistic missiles.[49] By October 2016, Japan was considering procuring either THAAD or Aegis Ashore to add a new missile defense layer.[50]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Terminal High Altitude Area Defense. |

- Arrow (Israeli missile)

- HQ-19

- M1120 HEMTT Load Handling System (launcher)

- Taiwan Sky Bow Ballistic Missile Defense System

- Indian Ballistic Missile Defence Programme

- S-300VM

- S-400 (SAM)

- NASAMS

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 "THAAD". Webcache.googleusercontent.com. Retrieved 24 January 2011.

- ↑ "PACOM Head Supports Exercises Near China, Talks THAAD",Defense News,February 25, 2016

- ↑ "Naver Dictionary:THAAD",Naver Dictionary

- ↑ "With an Eye on Pyongyang, U.S. Sending Missile Defenses to Guam". The Wall Street Journal, 3 April 2013.

- ↑ "Pentagon To Accelerate THAAD Deployment", Jeremy Singer, Space News, 4 September 2006

- ↑ "Lockheed Martin completes delivery of all components of 1st THAAD battery to U.S. Army",Yourdefencenews.com,March 8,2012

- ↑ "MDA's new THAAD success", Martin Sieff, UPI, 6 April 2007

- ↑ "Army, Navy and Air Force shoot down test missile", Tom Finnegan, Honolulu Star-Bulletin, Friday, 6 April 2007

- ↑ "Press Release by Lockheed Martin on Newswires". Texas: Prnewswire.com. 26 October 2007. Retrieved 24 January 2011.

- ↑ "31st successful 'hit to kill' intercept in 39 tests". Frontierindia.net. 27 October 2007. Retrieved 24 January 2011.

- ↑ "THAAD shoots down missile from C-17". The Associated Press, 27 June 2008

- ↑ Defense Test Conducted MDA 27 September 2008

- ↑ "Terminal High Altitude Area Defense". MDA. 17 March 2009. Archived from the original on 26 March 2009.

- ↑ "Officials investigating cause of missile failure". The Garden Island. 12 December 2009.

- ↑ "THAAD System Intercepts Target in Successful Missile Defense Flight Test". MDA. 29 June 2010.

- ↑ "THAAD Weapon System Achieves Intercept of Two Targets at Pacific Missile Range Facility". Lockheed Martin. 5 October 2011. Archived from the original on 9 December 2011.

- ↑ "FTI-01 Mission Data Sheet" (PDF). Missile Defense Agency. 15 October 2012.

- 1 2 "Ballistic Missile Defense System Engages Five Targets Simultaneously During Largest Missile Defense Flight Test in History". Missile Defense Agency. 25 October 2012.

- ↑ Butler, Amy (5 November 2012). "Pentagon Begins To Tackle Air Defense 'Raid' Threat". Aviation Week & Space Technology.

- 1 2 China’s Hypersonic Ambitions Prompt Thaad-ER Push – Aviationweek.com, 8 January 2015

- ↑ Thaad-ER In Search Of A Mission – Aviationweek.com, 20 January 2015

- ↑ U.S. Army has received the latest upgrade for THAAD air defense missile system – Armyrecognition.com, 2 January 2015

- ↑ "First Battery of THAAD Weapon System Activated at Fort Bliss". Lockheed Martin via newsblaze, 28 May 2008

- ↑ "First Battery of THAAD Weapon System Activated at Fort Bliss", Press Release, Lockheed Martin Official Website, 28 May 2008

- ↑ "Second Battery of Lockheed Martin's THAAD Weapon System Activated at Fort Bliss", Reuters (10-16-2009). Retrieved 20 October 2009.

- ↑ Lockheed Martin Receives $150 Million Contract To Produce THAAD Weapon System Equipment For The U.S. Army – Lockheed press release, 15 August 2012

- ↑ Gienger, Viola (18 June 2009). "Gates Orders Measures Against North Korea Missile (Update2)". Bloomberg. Retrieved 24 January 2011.

- ↑ "US to move missiles to Guam after North Korea threats". BBC. 3 April 2013. Retrieved 3 April 2013.

- ↑ Burge, David (9 April 2013). "100 bound for Guam: Fort Bliss THAAD unit readies for historic mission". El Paso Times. Retrieved 12 April 2013.

- ↑ "How a U.S. Radar Station in the Negev Affects a Potential Israel-Iran Clash." Time Magazine, 30 May 2012.

- ↑ "U.S. Maintains Full Control of Turkish-Based Radar" Defense Update, 30 January 2012

- ↑ "NATO Activates Radar in Turkey Next Week" Turkish Weekly Journal, 24 December 2011

- 1 2 3 2015 THAAD FTO2 Event2a accessdate=2016-07-14

- ↑ USS John Paul Jones participates in ballistic missile defense test, Ho'okele – Pearl Harbor – Hickam News, 6 November 2015, http://www.hookelenews.com/uss-john-paul-jones-participates-in-ballistic-missile-defense-test/

- ↑ U.S. completes complex test of layered missile defense system, Reuters, Anfrea Shalal, 1 November 2015, http://www.reuters.com/article/2015/11/02/us-usa-missile-defense-idUSKCN0SQ2GR20151102#A5FPzTc4GoPTGuvo.99

- ↑ United States Army has a plan to deploy THAAD air defense missile systems in South Korea – Armyrecognition.com, 29 May 2014

- ↑ Shala & Stewart, Andrea & Phil (25 February 2016). "China cites concerns on U.S. missile defense system in South Korea". Reuters. Reuters.

- ↑ Perez, Jane. "For China, a Missile Defense System in South Korea Spells a Failed Courtship". New York Times. New York Times. Retrieved 26 September 2016.

- ↑ THAAD To Officially Deploy to South Korea - Defensenews.com, 8 July 2016

- ↑ http://www.voanews.com/content/thaad-radition-fears-spark-south-korean-protests/3419467.html picked as site for THAAD battery - Koreatimes.co.kr, 12 July 2016

- ↑ THAAD Radiation Fears Spark South Korean Protests Voice of America 15 July 2016.

- ↑ S. Korea selects golf course as new site for THAAD - Yonhapnews.co.kr, 30 September 2016

- ↑ Army Weighing THAAD Deployments in Europe, Middle East – Defensenews.com, 22 March 2016

- ↑ "U.S., UAE reach deal for missile-defense system", CNN Wire Staff, CNN, 30 December 2011

- ↑ Oman to buy the air defense missile system THAAD – Armyrecognition.com, 27 May 2013

- ↑ Army of South Korea shows interest for the U.S. THAAD – Armyrecognition.com, 18 October 2013

- ↑ S. Korea to develop indigenous missile defense system instead of adopting THAAD – Sina.com, 3 June 2014

- ↑ 'S.Korea Requested Information on THAAD to Develop L-SAM' – KBS.co.kr, 5 June 2014

- ↑ Japan is considering deployement of US missile defense system including the THAAD – Armyrecognition.com, 24 November 2015

- ↑ Japan may accelerate missile defense upgrades in wake of North Korean tests: sources - Reuters.com, 17 October 2016

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Terminal High Altitude Area Defense. |

- Lockheed Martin THAAD web page

- Details of the project

- MDA THAAD page

- Program History

- http://www.airdefenseartillery.com/online/

DEM-VAL Test Program

EMD Test Program

- Successful THAAD Interceptor Launch Achieved, 22 November 2005

- Successful THAAD Integrated System Flight Test, 11 May 2006

- Successful THAAD Intercept Flight, 12 July 2006

- THAAD Equipment Arrives in Hawaii, October 18, 2006

- Successful THAAD "High Endo-Atmospheric" Intercept Test, January 27, 2007

- Successful THAAD Radar Target Tracking Test, March 8, 2007

- Successful THAAD "Mid Endo-Atmopsheric" Intercept, April 6, 2007

- THAAD Radar Supports Successful Aegis BMD Intercept, June 22, 2007

- Successful THAAD Interceptor Low-Altitude "Fly-Out" Test, June 27, 2007

_interceptors_is_launched_during_a_successful_intercept_test_-_US_Army.jpg)