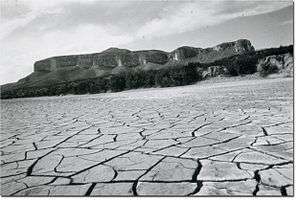

1950s Texas drought

The 1950s Texas drought was a period between 1949 and 1957, in which the state received 30 to 50 percent less rain than normal, while temperatures rose above average. During this time period, Texans experienced the second, third and eighth-driest single years ever in the state – 1956, 1954 and 1951, respectively.[1] The drought was described by a state water official as "the most costly and one of the most devastating droughts in 600 years."[2]

Effects

The drought began gradually, and some sources claim it began as early as 1947, starting with a decrease in rainfall in Central Texas. By the summer of 1951, the entire state was in drought. Texas ranchers attempted to evade the effects of the drought by moving their cattle north to Kansas, but the drought spread to Kansas and Oklahoma by 1953.[1] At that point, 75% of Texas recorded below normal rainfall amounts,[3] and over half the state was more than 30 inches below normal rainfall.[4] By 1954, the drought had affected a ten-state area reaching from the mid-west to the Great Plains, and southward into New Mexico.[3]

Economy

As a result of the devastating drought of the 1950s, the number of Texas farms and ranches shrank from 345,000 to 247,000, and the state's rural population declined from more than a third of the population to a quarter. Ranchers and farmers were hit the hardest by the dual threat of water scarcity and the increasing price of feed. The combined income of Texas farmers fell by one fifth from the previous year, and the price of low-grade beef cattle dropped from 15 to 5 cents a pound.[4] In 1940, 29 percent of employed Texans worked on a farm. That number fell to 12 percent in 1960.[2] Crop yields in some areas dropped as much as 50%.[3] Economic losses from 1950 to 1957 were estimated at $22 billion in 2011 dollars.[2]

Towns suffered from the drought as well, though it was different from the struggles of farmers. Across Texas, at least one thousand communities enforced some type of water restrictions. Some towns went completely dry and had to transport water in by truck or rail. The city of Dallas' reservoirs ran so low that water had to be pumped from the Red River, whose high salt content caused further trouble by damaging water pipes and plants. Corsicana experienced 82 days of temperatures over 100 degrees F, peaking at 113.[4]

West Texas was hit especially hard by the drought, particularly the city of San Angelo, where President Dwight D. Eisenhower visited in 1957 to assess the effects of the drought just before it ended.[4]

Environment

The severe drought also had a lasting effect on the Texas environment. Without new grass growth, cattlemen overgrazed their pastures, which damaged the land and made it more susceptible to mesquite and cedar intrusion. Poor soil conservation practices left the topsoil vulnerable, and when the drought began, strong winds swept the dirt and dust into the sky. This led to persistent dust storms that rivaled those during the Dust Bowl.[4]

Government intervention

The situation became so dire that the US government began distributing emergency feed supplies to desperate farmers. Some farmers resorted to feeding their animals prickly pears or molasses to keep them alive.[4] In 1956, the New York Times reported that more than 100,000 Texans were receiving surplus “federal food commodities."[5] By the time the drought subsided in 1957, many counties across the region were declared federal drought disaster areas, including 244 of the 254 counties in Texas.[3]

On January 13, 1957, President Eisenhower and Agriculture Secretary Ezra Taft Benson visited San Angelo as part of a six-state inspection tour of the drought. There, he made a speech to the people that his administration would do whatever they could to alleviate the hardship of the drought.[4]

Rain returns

Shortly after the president's visit, rain finally came. Intermittent January rains gave way to downpours in February, which continued through the spring and summer seasons. April 24, 1957 saw a storm bring 10 inches of rain on a large portion of Texas within a few hours, accompanied by destructive hail and multiple tornadoes. The rain continued for 32 days, and the floods killed 22 people and forced thousands from their homes.[6] Every major river in Texas flooded, washing out bridges and sweeping away houses. Damages were estimated at $120 million, which still paled in comparison to the damage caused by the drought itself.[7]

Prevention

In the hope of preventing such a crisis from happening again, the state developed drought contingency plans, expanded the state's water storage and sought new sources of groundwater. The state created the Texas Water Development Board in 1957, which set into motion a number of water conservation plans.[5] An amendment to the Texas constitution in 1957 authorized the issuance of $200 million in loans to municipalities for conservation and development of water resources.[8] The number of Texas reservoirs more than doubled by 1970,[4] and by 1980 more than 126 major reservoirs had been constructed.[8] State and federal departments of agriculture set up safeguard programs to help farmers handle future severe droughts, including low-interest emergency loans and emergency access to hay and grazing land.[2]

The state began a number of efforts to increase water supply, building dams, forming lakes, and tapping into underground sources of water. From 1947 to 1957, groundwater use increased fivefold. As the drought spurred farmers to find more water sources, cheaper pumps were made available. From 1957 to 1970, workers built 69 dams, including Longhorn Dam on the Colorado River, which formed Lady Bird Lake in 1960.[2] Today, Texas has more surface areas of lake than any state except Minnesota.[9]

The 1950s drought continues to remain a model for water conservation plans in the present day, with Texas water authorities using the effects of the drought's severity to create water plans.[5]

Popular culture

The 1950s Texas drought has been written about by a number of Texans who experienced it, including Elmer Kelton, renowned western novelist and agricultural journalist, whose novel The Time It Never Rained is still regarded as the best account of the period.[4]

See also

References

- 1 2 Brown, Angela (14 August 2011). "Texas Drought Recalls Long, Punishing Dry Spell Of 1950's". The Huffington Post. TheHuffingtonPost.com, Inc. Retrieved 2016-03-03.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Mashhood, Farzad (4 August 2011). "Current drought pales in comparison with 1950s 'drought of record". Statesman. Statesman Media. Retrieved 2016-03-04.

- 1 2 3 4 "Drought: A Paleo Perspective". National Centers for Environmental Information. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 2016-03-04.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Burnett, John (July 2012). "When the Sky Ran Dry". Texas Monthly. Texas Monthly. Retrieved 2016-03-03.

- 1 2 3 Tedesco, John (11 September 2015). "1950s drought plagued Texas for seven long years". San Antonio Express-News. Retrieved 2016-03-04.

- ↑ "Texas Water Issues: Major Droughts in Modern Texas | TSLAC". Texas State Library and Archives Commission. State of Texas. 18 June 2015. Retrieved 2016-03-04.

- ↑ Burnett, John (7 July 2012). "How One Drought Changed Texas Agriculture Forever". NPR.org. National Public Radio. Retrieved 2016-03-04.

- 1 2 Wythe, Kathy. "The time it never rained". twri.tamu.edu. Texas Water Resources Institute. Retrieved 2016-03-10.

- ↑ "Texas State Parks in the 1950s - Texas State Library | TSLAC". www.tsl.texas.gov. Retrieved 2016-03-04.