Black Dahlia

| Elizabeth Short "Black Dahlia" | |

|---|---|

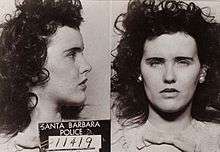

Short's September 1943 mugshot | |

| Born |

July 29, 1924 Hyde Park, Boston, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Died |

c. January 15, 1947 (aged 22) Los Angeles, California, U.S.[1] |

| Resting place | Mountain View Cemetery, Oakland, California |

| Occupation | Waitress |

| Parent(s) |

Cleo Short (father) Phoebe Mae Sawyer (mother) |

"The Black Dahlia" was a nickname given to Elizabeth Short[2][3][4] (July 29, 1924 – c. January 15, 1947), an American woman who was the victim of a much-publicized murder in 1947. Short acquired the moniker posthumously from newspapers in the habit of nicknaming crimes they found particularly lurid. The "Black Dahlia" nickname may have been derived from a film noir murder mystery, The Blue Dahlia, released in April 1946. Short was found mutilated, her body sliced in half at the waist, on January 15, 1947, in Leimert Park, Los Angeles, California. Short's unsolved murder has been the source of widespread speculation, leading to many suspects, along with several books, television and film adaptations of the story. Short's murder is one of the oldest unsolved murder cases in Los Angeles history.[1]

Early life

Short was born in Hyde Park, Boston, the third of five daughters of Cleo and Phoebe May (Sawyer) Short. She grew up in Medford, Massachusetts, a Boston suburb. Her father built miniature golf courses until the 1929 stock market crash, when he lost most of his money. One day in 1930, he parked his car on a bridge and was not heard from for years,[5] leading many to presume he had committed suicide. Phoebe May Short moved her family into a small apartment in Medford and went to work as a bookkeeper to support them. It was not until a letter of apology was received that the family learned Cleo Short was still alive, and living in California.

Troubled by asthma and bronchitis, Elizabeth Short was sent at age sixteen to spend the winter in Miami. During the next three years, she lived in Florida during the cold months and spent the rest of the year in Medford. At age nineteen, she travelled to Vallejo, California, to live with her father, who was working at the nearby Mare Island Naval Shipyard on San Francisco Bay. Early in 1943, Short and her father moved to Los Angeles, but she left him following an argument, and took a job at the post exchange at Camp Cooke (now Vandenberg Air Force Base), near Lompoc, California. She soon moved to Santa Barbara, where she was arrested on September 23, 1943 for underage drinking. The juvenile authorities sent her back to Medford, but she returned instead to Florida, and made only occasional visits to Massachusetts.

While in Florida, Short met Major Matthew Michael Gordon, Jr., a decorated United States Army Air Force officer then at the 2nd Air Commando Group, where he was training for deployment to the China Burma India Theater of Operations. She told friends that he had written to propose marriage while he was recovering from injuries from a plane crash in India. She accepted his offer, but Gordon died in a second crash on August 10, 1945, less than a week before Japan's surrender ended World War II.

Short returned to Los Angeles in July 1946 to visit Army Air Force Lieutenant Joseph Gordon Fickling, whom she knew from Florida. Fickling was stationed at the Naval Reserve Air Base, Long Beach. Short spent the last six months of her life in southern California, mostly in the Los Angeles area.

Murder and aftermath

On the morning of January 15, 1947, Elizabeth Short's naked body was found in two pieces on a vacant lot on the west side of South Norton Avenue midway between Coliseum Street and West 39th Street (at 34°00′59″N 118°19′59″W / 34.0164°N 118.333°W) in Leimert Park, Los Angeles. Local resident Betty Bersinger discovered the body at about 10:00 am, as she was walking with her three-year-old daughter.[1][6] Bersinger at first thought it was a discarded store mannequin.[1] When she realized it was a corpse, she rushed to a nearby house and telephoned the police.[1]

Short's severely mutilated body was completely severed at the waist and drained entirely of blood.[7] The body obviously had been washed by the killer.[8] Short's face had been slashed from the corners of her mouth to her ears, creating an effect called the Glasgow smile. Short had several cuts on her thigh and breasts, where entire portions of flesh had been sliced away.[1] The lower half of her body was positioned a foot away from the upper, and her intestines had been tucked neatly beneath her buttocks.[8] The corpse had been "posed", with her hands over her head, her elbows bent at right angles, and her legs spread apart.[1][5] Detectives found a cement sack nearby containing watery blood. There was a heel print on the ground amid the tire tracks.[1]

An autopsy stated that Short was 5 feet 5 inches (1.65 m) tall, weighed 115 pounds (52 kg), and had light blue eyes, brown hair, and badly decayed teeth. There were ligature marks on her ankles, wrists, and neck. The skull was not fractured, but Short had bruises on the front and right side of her scalp, with a small amount of bleeding in the subarachnoid space on the right side, consistent with blows to the head.[1] The cause of death was determined to be hemorrhaging from the lacerations to her face and shock from blows on the head and face.

Following Short's identification, reporters from the Los Angeles Examiner contacted her mother, Phoebe Short, and told her that her daughter had won a beauty contest. Only after prying as much personal information as they could from Phoebe, did the reporters tell her that her daughter had been murdered. The newspaper offered to pay her air fare and accommodations, if she would travel to Los Angeles to help with the police investigation. That was yet another ploy, since the newspaper kept her away from police and other reporters to protect its scoop.[9] William Randolph Hearst's papers, the Los Angeles Herald-Express and the Los Angeles Examiner, later sensationalized the case: the black tailored suit Short was last seen wearing became "a tight skirt and a sheer blouse", and Elizabeth Short became the "Black Dahlia", an "adventuress" who "prowled Hollywood Boulevard".

On January 23, 1947, a person claiming to be the killer called the editor of the Los Angeles Examiner, expressing concern that news of the murder was tailing off and offering to mail items belonging to Short to the editor. The following day, a packet arrived at the Los Angeles newspaper containing Short's birth certificate, business cards, photographs, names written on pieces of paper, and an address book with the name Mark Hansen embossed on the cover. Hansen, an acquaintance at whose home she had stayed with friends, immediately became a suspect. One or more others wrote more letters to the newspaper, signing them "the Black Dahlia Avenger", after the name given Short by the newspapers. On January 25, Short's handbag and one shoe were reported seen on top of a garbage can in an alley a short distance from Norton Avenue. They were finally located at the dump.

Due to the notoriety of the case, over the years more than fifty men and women have confessed to the murder, with police receiving large amounts of information from citizens every time a newspaper mentions the case or a book or movie is released about it. Sergeant John P. St. John, a detective who worked the case until his retirement, stated, "It is amazing how many people offer up a relative as the killer".

Short was buried at the Mountain View Cemetery in Oakland, California. After her sisters had grown up and married, Phoebe Short moved to Oakland to be near her daughter's grave. She finally returned to the east coast in the 1970s, where she lived into her nineties.[5]

Rumors and popular misconceptions

According to newspaper reports shortly after the murder, Elizabeth Short received the nickname "Black Dahlia" at a Long Beach, California, drugstore in mid-1946 as wordplay on the film The Blue Dahlia. Los Angeles County district attorney investigators' reports state that the nickname was invented by newspaper reporters covering the murder. Los Angeles Herald-Express reporter Bevo Means, who interviewed Short's acquaintances at the drug store, is credited with first using the "Black Dahlia" name.[10]

A number of people, none of whom knew Short, contacted police and the newspapers, claiming to have seen her during her so-called "missing week" between her January 9 disappearance and the discovery of her body on January 15. Police and district attorney investigators ruled out each of these alleged sightings; in some cases, those interviewed were identifying other women they had mistaken for Short.[11]

Many true-crime books claim that Short lived in or visited Los Angeles at various times in the mid-1940s; these claims have never been substantiated and are refuted by the findings of law enforcement officers who investigated the case. A document in the Los Angeles County district attorney's files titled "Movements of Elizabeth Short Prior to June 1, 1946" states that Short was in Florida and Massachusetts from September 1943 through the early months of 1946 and gives a detailed account of her living and working arrangements during this period. Although a popular portrayal amongst her acquaintances and many true-crime authors was of Short as a call girl, the Los Angeles district attorney's grand jury proved there was no existing evidence that she was ever a prostitute, and the district attorney's office attributes the claim to confusion with another woman with the same name. A widely circulated rumor also holds that Short was unable to have sexual intercourse because of a congenital defect which had left her with "infantile genitalia". Los Angeles County district attorney's files state that the investigators had questioned three men with whom Short had engaged in sex,[12] including a Chicago police officer who was a suspect in the case.[13] The FBI files on the case also contain a statement from one of Short's alleged lovers. Found in the Los Angeles district attorney's files and in the Los Angeles Police Department's summary of the case, Short's autopsy describes her reproductive organs as anatomically normal, although the report notes evidence of what it called "female trouble". The autopsy also states that Short was not and had never been pregnant, contrary to what had been claimed prior to and following her death.[12]

Suspects

The Black Dahlia murder investigation was conducted by the LAPD. The Department also enlisted the help of hundreds of officers borrowed from other law enforcement agencies. Owing to the nature of the crime, sensational and sometimes inaccurate press coverage focused intense public attention on the case.

About sixty people confessed to the murder, mostly men. Of those, twenty-five were considered viable suspects by the Los Angeles District Attorney. In the course of the investigation, some of the original twenty-five were eliminated, and several new suspects were proposed. Suspects remaining under discussion by various authors and experts include Walter Bayley,[14] Norman Chandler, Leslie Dillon, Joseph A. Dumais, Mark Hansen, Dr. Francis E. Sweeney, George Hill Hodel, Hodel's friend Fred Sexton,[15] George Knowlton, Robert M. "Red" Manley, Patrick S. O'Reilly, and Jack Anderson Wilson.[16]

Theories and possibly related murders

Some crime story authors have speculated on a link between the Short murder and the Cleveland Torso Murders, which took place in Cleveland between 1934 and 1938.[17] As with a large number of killings that took place before and after the Short murder, the original LAPD investigators looked into the Cleveland murders in 1947 and later discounted any relationship between the two cases. Nevertheless, new evidence implicating a former Cleveland torso murder suspect, Jack Anderson Wilson (a.k.a. Arnold Smith), was investigated by Detective John P. St. John in 1980 in connection with Short's death. St. John claimed he was close to arresting Wilson for the murder of Short, but Wilson died in a fire on February 4, 1982.[18]

Crime story authors such as Steve Hodel (son of George Hill Hodel) and William Rasmussen have suggested a link between the Short murder and the 1946 murder and dismemberment of six-year-old Suzanne Degnan in Chicago.[19] Captain Donahoe of the Los Angeles police stated publicly that he believed the Black Dahlia and the Lipstick Murders were "likely connected".[20] Among the evidence cited is the fact that Elizabeth Short's body was found on Norton Avenue three blocks west of Degnan Boulevard, Degnan being the last name of the girl from Chicago. There were also striking similarities between the Degnan ransom note and that of "the Black Dahlia Avenger". Both texts used a combination of capitals and small letters (the Degnan note read in part "BuRN This FoR heR SAfTY" [sic]), and both notes contain a similar misshapen letter P and have one word that matches exactly.[21] Convicted serial killer William Heirens served life in prison for Degnan's murder. Initially arrested at age 17 for breaking into a residence close to that of Suzanne Degnan, Heirens claimed he was tortured by police, forced to confess, and made a scapegoat for the Degnan murder.[22]After being taken from the medical infirmary at the Dixon Correctional Center on February 26, 2012, due to health problems, Heirens died at the University of Illinois Medical Center on March 5, 2012, at the age of 83.

Fictional portrayals

A television dramatization, "Who Is the Black Dahlia?" (1975), featured Lucie Arnaz in the role of Elizabeth Short. The case has inspired numerous works of fiction, among them a 1977 novel by John Gregory Dunne, later made into the film True Confessions starring Robert De Niro and Robert Duvall. James Ellroy's 1987 novel The Black Dahlia is a fictionalized account that, like Dunne's, uses the case as an occasion for "an exploration of the larger fields of politics, crime, corruption, and paranoia in post-war Los Angeles", according to cultural critic David M. Fine.[23] Brian De Palma's 2006 film The Black Dahlia, based on Ellroy's novel, bears little relation to the facts of the case.[24] Joyce Carol Oates wrote a short story titled "Black Dahlia and White Rose", which uses multiple narrators, including Elizabeth Short herself, published in her story collection of the same name and winner of the Horror Writers of America's Bram Stoker Award. Elizabeth Short also appears in Craig McDonald's 2008 novel, Toros & Torsos. In 2011 Short appeared in an episode of American Horror Story, played by Mena Suvari. A fictionalized version of the Black Dahlia appears in the video game L.A. Noire, where the murder happens because of a serial killer. In James Ellroy's novel The Black Dahlia there is a fictional resolution in which a wealthy Hollywood family is responsible for the murder.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Black Dahlia. |

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Gilmore, John (2001). Severed: The True Story of the Black Dahlia Murder. Amok. ISBN 978-1-878923-17-2.

- ↑ "Investigation : Birth Certificate". Blackdahlia.info. Retrieved 2010-02-02.

Copy of Short's registered birth certificate showing that no middle name was included

- ↑ Coroner's Inquest Transcript Inquest Held on the Body of Elizabeth Short, Phoebe Short testimony (Hall of Justice, Los Angeles, California 1947-01-22).

- ↑ "Common Myths About the Black Dahlia and Their Origins". Larry Harnisch. Retrieved February 2, 2010.

- 1 2 3 Harnisch, Larry. "A Slaying Cloaked in Mystery and Myths". Los Angeles Times. January 6, 1997.

- ↑ "Black Dahlia (Notorious Murders, Most Famous)". trutv.com. Retrieved 2010-07-22.

- ↑ McLellan, Dennis (January 9, 2003). "Obituaries: Ralph Asdel, 82; Detective in the Black Dahlia Case". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2010-02-25.

- 1 2 Scheeres, Julia. "Macabre Discovery". The Black Dahlia. Retrieved 2013-10-08.

- ↑ Haugen, Brenda (2010). The Black Dahlia: Shattered Dreams. Capstone Publishers. pp. 9–12. ISBN 978-0-7565-4358-7.

- ↑ Rob Leicester Wagner. "Red Ink, White Lies: The Rise and Fall of Los Angeles Newspapers, 1920–1962 by Rob Leicester Wagner, Dragonflyer Press, 2000". Openlibrary.org. Retrieved 2014-07-14.

- ↑ Excerpts From Grand Jury Summary BlackDahlia.info. Access date: November 4, 2007.

- 1 2 Fact Versus Fiction BlackDahlia.info.

- ↑ District Attorney Suspects BlackDahlia.info.

- ↑ "The Black Dahlia Murder Theory Part 2/3". YouTube. 2009-09-30. Retrieved 2014-07-14.

- ↑ Hodel, Steve. Black Dahlia Avenger. Arcade. New York. 2003.

- ↑ Suzan Nightingale (January 17, 1982). "Black Dahlia: Author Claims to Have Found 1947 Killer". Los Angeles Herald Examiner.

- ↑ Bardsley, Marilyn. "The Cleveland Torso Murders aka Kingsbury Run Murders - Eliot Ness Case - Crime Library on truTV.com". Crimelibrary.com. Archived from the original on 2014-07-24. Retrieved 2014-07-14.

- ↑ William T. Rasmussen Corroborating evidence II Sunstone Press, 2006 ISBN 0-86534-536-8 pg 80-97

- ↑ "The Black Dahlia: The Unsolved Murder of Elizabeth Short — Black Dahlia Intro — Crime Library on". Trutv.com. 2003-04-11. Retrieved 2010-08-12.

- ↑ William T. Rasmussen Corroborating evidence II pg 101

- ↑ William T. Rasmussen Corroborating evidence II Pg 122

- ↑ William T. Rasmussen Corroborating evidence II Pg 48-70

- ↑ Fine, David M. (2004). Imagining Los Angeles: A City in Fiction. University of Nevada Press. pp. 209–210. ISBN 0-87417-603-4.

- ↑ Mayo, Mike (2008). American Murder: Criminals, Crimes, and the Media. Visible Ink Press. p. 316. ISBN 1-57859-256-9.

Further reading

- Daniel, Jacque (2004). The Curse of the Black Dahlia. Los Angeles: Digital Data Werks. ISBN 0-9651604-2-4.

- Fowler, Will (1991). Reporters: Memoirs of a Young Newspaperman. Minneapolis: Roundtable Publishing. ISBN 0-915677-61-X.

- Gilmore, John (2006) [1994]. Severed: The True Story of the Black Dahlia. Los Angeles: Amok Books. ISBN 1-878923-17-X.

- Hodel, Steve (2003). Black Dahlia Avenger: A Genius for Murder. New York: Arcade Publishing. ISBN 1-55970-664-3.

- Knowlton, Janice; Newton, Michael (1995). Daddy Was the Black Dahlia Killer. New York: Pocket Books. ISBN 0-671-88084-5.

- Nelson, Mark; Bayliss, Sarah Hudson (2006). Exquisite Corpse: Surrealism and the Black Dahlia Murder. New York: Bulfinch Press. ISBN 0-8212-5819-2.

- Pacios, Mary (1999). Childhood Shadows: The Hidden Story of the Black Dahlia Murder. Bloomington, IN: Authorhouse. ISBN 1-58500-484-7.

- Rasmussen, William T. (2005). Corroborating Evidence: The Black Dahlia Murder. Santa Fe, NM: Sunstone Press. ISBN 0-86534-536-8.

- Richardson, James (1954). For the Life of Me: Memoirs of a City Editor. New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons. (ISBN unavailable).

- Smith, Jack (1981). Jack Smith's L.A. New York: Pinnacle Books. ISBN 0-523-41493-5.

- Underwood, Agness (1949). Newspaperwoman. New York: Harper and Brothers. (ISBN unavailable).

- Wagner, Rob Leicester (2000). Red Ink, White Lies: The Rise and Fall of Los Angeles Newspapers, 1920–1962. Upland, Calif.: Dragonflyer Press. ISBN 0-944933-80-7.

- Webb, Jack (1958). The Badge: The Inside Story of One of America's Great Police Departments. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall. ISBN 0-09-949973-8.

- Wolfe, Donald H. (2005). The Black Dahlia Files: The Mob, the Mogul, and the Murder That Transfixed Los Angeles. New York: ReganBooks. ISBN 0-06-058249-9.

External links

- The FBI's Black Dahlia files from the FBI's Freedom of Information Act site.

- "Somebody Knows" episode a 1950 radio program on the case.

- "Black Dahlia". Find a Grave. Retrieved June 10, 2013.