The Jewel of Seven Stars

Cover of the first edition | |

| Author | Bram Stoker |

|---|---|

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Genre | Horror novel |

| Publisher | Heinemann |

Publication date | 1903 |

| Media type | Print (hardcover) |

| Pages | 337 |

| OCLC | 11975302 |

| LC Class | PZ3.S8743 J PR6037.T617[1] |

The Jewel of Seven Stars is a horror novel by Bram Stoker, first published by Heinemann in 1903. The story is a first-person narrative of a young man pulled into an archaeologist's plot to revive Queen Tera, an ancient Egyptian mummy. It explores common fin-de-siecle themes such as imperialism, the rise of the New Woman and feminism, and societal progress.

Prepublication issues toward a US edition were deposited for copyright by Doubleday, Page & Company in December 1902 and January 1903 but the first US edition was published by Harper & Brothers in 1904.[1][2]

Plot summary

Malcolm Ross, a young barrister, is awakened in the middle of the night and summoned to the house of famous Egyptologist Abel Trelawny at the request of his daughter, Margaret, with whom Malcolm is enamored. Once Malcolm arrives at the house, he meets Margaret, Superintendent Dolan, and Doctor Winchester, and learns why he has been called: Margaret, hearing strange noises from her father’s bedroom, woke to find him unconscious and bloodied on the floor of his room, under some sort of trance. Margaret reveals that her father had left a letter of strange instructions in the event of his incapacitation, stating that his body should not be removed from his room and must be watched at all times until he wakes up. The room is filled with Egyptian relics, and Malcolm notices that the "mummy smell" has an effect on those in the room. A large mummy cat in the room disturbs Margaret’s cat, Silvio, and the doctor suspects Silvio is guilty of the scratch marks on Trelawny’s arm.

On the first night of watch, Malcolm awakens to find Trelawny again on the floor, bloody and senseless. Margaret asks Dr. Winchester to summon another expert, and he calls for Dr. James Frere, a brain specialist. However, when Frere demands that Trelawny be moved from his room, Margaret refuses and sends him away. After a normal night with no attacks, a stranger arrives, begging to see Trelawny. He reveals himself to be Eugene Corbeck, an Egyptologist who was working with Trelawny. He has returned from Egypt with lamps that Trelawny requested, but finds upon his arrival at the house that the lamps have disappeared. The next day, Malcolm and Margaret admire Trelawny’s Egyptian treasures, noting in particular a large sarcophagus, a coffer covered with hieroglyphics, and an oddly well-preserved mummy hand with seven fingers. Malcolm then finds the missing lamps in Margaret’s bedroom. Concerned for Margaret, Malcolm tells Corbeck everything that has happened up until his arrival, and Corbeck gives Malcolm a mysterious book to read. The book tells the story of Nicholas van Huyn, a Dutch explorer who travelled to the Valley of the Sorcerer to explore the tomb of a mysterious Egyptian queen, Tera. In the tomb, he finds a sarcophagus and a mummy hand with seven fingers, adorned with a ruby ring with seven points that look like stars.

Corbeck tells Malcolm that, years ago, he and Trelawny travelled to Egypt to search for the tomb where the sarcophagus lies. They find the tomb and discover that the mummy’s wrist was coated with fresh dried blood. The hieroglyphics on the wall led Corbeck and Trelawny to believe that the mummy was possessed with some sort of black magic and that Queen Tera had immense power over the Upper and Lower Worlds. The hieroglyphics seemed to indicate that Tera planned to return from the dead. They took the sarcophagus from the tomb and left, only to be robbed of the mummy during a storm by their Arab guides. Trelawny suggested that they return to the tomb, where they found the mummy and the three Arabs, murdered. During their time in the tomb, they were put under some trance and recovered three days later to find that Trelawny’s wife had died in childbirth, but Margaret survived. Sixteen years passed before Trelawny contacted Corbeck, frantic because he believed that the lamps they saw in the tomb, when arranged in a specific shape, would make the coffer open and would possibly be the key to Tera’s resurrection.

Corbeck’s story is interrupted by Trelawny’s revival. He embraces his daughter and joyfully approves Malcolm’s courtship. Dolan and the police depart, glad to escape from the mystery, and Trelawny gathers the remaining inhabitants of the house to explain his Great Experiment. He describes how powerful Queen Tera was and explains that her spirit has been residing in the mummy cat in Trelawny’s room, waiting to be reunited with its human form. Trelawny believes that the coffer, when opened by the proper formation of the lamps, will release some sort of magic that will revive the mummy and bring Tera’s spirit to life. Trelawny’s attack was the attempt of Tera’s astral body—the mummy cat—to remove the Jewel of Seven Stars from a locked safe in his bedroom. He reveals that he has prepared a house in isolated Kyllion where the experiment is to take place.

After this overwhelming wealth of information is revealed, Malcolm questions the implications of ancient forces interacting with new civilization. He worries about the impact on religion and monotheism if the power of the ancient Egyptian gods is proven. Trelawny also posits that the ancient Egyptians possessed contemporary scientific knowledge, such as the discovery of radium and invention of electricity. Once everyone arrives at the new house, Margaret’s behavior becomes increasingly erratic, and she seems to have an uncanny knowledge of Tera’s thoughts and feelings. Malcolm begins to suspect that Margaret is the astral body of Tera and fears that she will be too weak to fight off a possession, but when he relays these concerns to Trelawny and Margaret, they seem unafraid of this possibility.

On the night of the experiment, a wild storm rages outside as they set up in a cave underneath the house. Margaret tells her father that Tera will not possess the mummy cat and will remain powerless until the experiment is complete, seeming to confirm that Margaret has been possessed. Somehow comforted by the confirmation of Tera’s existence, they proceed with the experiment and unwrap the mummy. They discover that Tera is wearing a marriage robe, which greatly distresses Margaret. Malcolm is put in charge of turning on the electric lights after the experiment ends, and Margaret blows out the candles. As the lamps are lit, the coffer begins to glow, emitting a green vapour that passes into the sarcophagus. Suddenly, the wind from the storm shatters a window, blowing the vapour around the room, and black smoke pours out of the coffer. The room is engulfed in smoke, and Malcolm waits for the command to turn on the lights, but it never comes. The lamps slowly burn out and Malcolm fumbles in the dark, coming across the limp body of a woman whom he believes is Margaret. He carries her upstairs and leaves her in the hall while he runs for matches, but when he returns, he finds only Tera’s bridal robe lying on the floor, the Jewel of Seven Stars lying where the heart would be. He returns to the cave and turns on the lights to find all of his companions on the floor, dead.

In a revised version released in 1912, this ending was removed. In the second version, the experiment fails entirely, no one is harmed, and Margaret and Malcolm marry a few years later.

Characters

- Malcolm Ross: The protagonist and narrator, Malcolm is drawn into the mystery of Queen Tera by his love for Margaret Trelawny, and his desire to protect her guides most of his actions.

- Margaret Trelawney: The daughter of Abel, born while Abel was entranced in Tera’s tomb, Margaret begins as a demure and sweet woman but grows more independent throughout the text. She strongly resembles Queen Tera and eventually takes on similar characteristics, possibly being possessed by Tera’s spirit.

- Abel Trelawny: A famous Egyptologist who becomes obsessed with the idea of resurrecting Tera. A hopeful, ambitious, and fearless man, he is extremely interested in scientific progress and believes that the ancient Egyptians were more progressive than the contemporary British.

- Eugene Corbeck: An Egyptologist who aids Trelawny in his endeavors to recover Egyptian artifacts. A little bit feisty, he seems more interested in the artifacts than the idea of resurrecting Tera. His enthusiasm wanes and his anxiety grows as the Great Experiment goes from theory to reality.

- Doctor Winchester: A young doctor who initially comes to treat Trelawny for his wounds but becomes entangled in the mystery. Though he is hesitant at first to give up on factual evidence, he shows a willingness to believe in the supernatural and eagerly assists in the revival.

Historical background

Egyptomania

In 1882, the British government began its efforts to colonize Egypt, declaring it a protectorate.[3] However, the Victorian-era fascination with Egypt had risen at the start of the nineteenth century, when European exploration of Egypt began. Archaeological discoveries of ancient Egyptian tombs and monuments such as Cleopatra’s Needle and the Rosetta Stone sparked the interest of European scholars and travelers.[4] The colonization of Egypt made it easier to bring these monuments back to Britain, and "there soon arose a demand for antiquities from Egypt to be shipped to private manors in Europe as well as to public museums. It became popular for mummies to take up residence in the libraries and studies of rich Europeans and for houses to be decorated with Egyptian motifs and artifacts".[5]

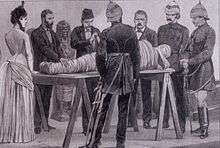

Egyptology and the fascination with ancient artifacts were echoed in nineteenth-century literature. Between 1860 and 1914, hundreds of stories about Egyptian mummies, curses, and exploration were published. Roger Luckhurst situates this within a cultural trend of what he calls Egyptian Gothic, "a set of beliefs or knowledges in a loosely occult framework" developed in response to British anxieties about the rule of Egypt.[6] One common plot in these narratives was the "Mummy’s Curse", which "follows the basic plot structure of misappropriation of tomb artifacts with fatal consequences following the protagonist home and features the explicit warning 'beware of the Mummy’s Curse'”;[7] often these artifacts were possessed by some supernatural element. Mummies were often the focal point of these stories, usually of noble rank, because most of the mummies being discovered in the nineteenth century were pharaohs. There was an emphasis on the idea of perfect preservation and beauty; mummies were unraveled at museum exhibitions in British museums, and audiences were amazed by their "almost perfect condition".[8] Because of their preserved beauty, female mummies in Victorian fiction were often eroticized objects of desire.[9]

Queen Hatshepsut

Though Queen Tera is an entirely fictional character, she bears many resemblances to Queen Hatshepsut, a pharaoh in Ancient Egypt. Hatshepsut ruled Egypt from 1479 BC to 1458 BC, one of the first and few female rulers. She married her half-brother, Tuthmose II, who ruled from 1492 BC until his death in 1479 BC. At this point, Hatshepsut became regent to Tuthmose’s son, by a concubine, her half-nephew. Rather than being regent to the toddler king, however, Hatshepsut took the throne and declared herself ruler. However, because Egyptian kingship was intrinsically masculine, Hatshepsut publicly transformed her feminine self; all statues and "images of her after her coronation show her as a man—wide shoulders, trim hips, and no hint of breasts".[10] About twenty years after her death in 1458 BC, her name and image was removed from temple walls, and many of her statues were destroyed. Dorman argues that this was not personal animosity, but rather an attempt to eradicate any hints of an unconventional, female ruler, "best erased to prevent the possibility of another powerful female ever inserting herself into the long line of Egyptian male kings".[11]

The tomb of Queen Hatshepsut was discovered by Howard Carter early in 1903, the same year as the publication of The Jewel of Seven Stars, in the Valley of the Kings—similar to the Valley of the Sorcerer, where Tera is found in the novel.[12] The similarities between the two, Hebblethwaite states, are "almost too overt to be mere coincidence";[13] both are extremely powerful female rulers who take on the role of men. Just as Hatshepsut commanded and transfigured her masculine image, it is found in Tera’s tomb that "[p]rominence was given to the fact that she, though a Queen, claimed all the privileges of kingship and masculinity. In one place she was pictured in man’s dress, and wearing the White and Red Crowns. In the following picture she was in female dress, but still wearing the Crowns of Upper and Lower Egypt, while the discarded male raiment lay at her feet".[14] Both Tera and Hatshepsut also seemed to possess some awareness that their legacy would be destroyed. In the novel, Tera leaves an inscription stating her plans for resurrection, as well as that "the hatred of the priests was, she knew, stored up for her, and that they would after her death try to suppress her name".[15] A similar inscription was found on an obelisk at Hatshepsut’s memorial: "Now my heart turns this way and that, as I think what the people will say—those who shall see my monuments in years to come, and who shall speak of what I have done".[11]

Literary background

Bram Stoker

Stoker’s own knowledge of Egyptology can be seen in his painstaking attention to historical accuracy in The Jewel of Seven Stars. The Egyptian artifacts are described in laborious detail, contemporary Egyptologists such as Flinders Petrie and Wallis Budge are referenced, and "the many mentions of ancient Egyptian gods, funerary practices and traditional customs that pepper the novel testify to the author’s profound knowledge of his subject".[16] Stoker studied at Trinity College Dublin, which boasted a notable program in Orientalism, where many early Orientalists and Egyptologists studied.[17] According to several biographies of Stoker, he was close with Sir William Wilde—the father of Oscar—who was an Egyptology enthusiast, and often shared the stories of his adventures with Stoker. On one voyage in 1837, Wilde discovered a mummy outside of a tomb near Saqqara and brought it back to Dublin; Belford argues that this would later inspire Stoker to write a mummy story.[18] Stoker references his friendship with another Orientalist explorer, Sir Richard Francis Burton, in his Personal Reminiscences of Henry Irving. Burton, an explorer of the Middle East and Africa, wrote and published many accounts of his travels, and Stoker admired his adventures and discoveries: "Burton had the most vivid way of putting things—especially of the East. He had both a fine imaginative power and a memory richly stored not only from study but from personal experience….Burton knew the East. Its brilliant dawns and sunsets…the mysteries of its veiled women; its romances; its beauty; its horrors".[19] Inspired by the stories of Egypt he heard, Stoker dedicated himself to the study of Egyptology; Stoker was known to own a number of texts on Egyptology, including William Wilde’s Narratives of a Voyage to Madeira, Wallis Budge’s Easy Lessons in Egyptian Hieroglyphics, Egyptian Religion: Egyptian Ideas on the Future Life, and Flinders Petrie’s Egyptian Tales Translated from the Papyri.[20]

Genre

Imperial Gothic

The Jewel of Seven Stars, from its placement during the fin-de-siecle, is an example of Imperial Gothic. Influenced by anxiety over the decline of the British Empire, Imperial Gothic texts employ elements of Gothic literature, such as darkness, death, sexuality, and the occult, and combine them with concerns about imperialism, colonialism, and nineteenth-century politics. Brantlinger notes three key themes of Imperial Gothic: "individual regression or going native; an invasion of civilization by the forces of barbarism or demonism; and the diminution of opportunities for adventure and heroism in the modern world".[21] Imperial Gothic is marked by a fear of the future, expressing these anxieties as supernatural events that are equally uncontrollable. The Jewel of Seven Stars represents a specific fear, which Brantlinger labels the "invasion scare story": in a reversal of the "outward thrust of imperialist adventure", a foreign body gains power and threatens the existing structure of civilization.[22] In The Jewel of Seven Stars, Queen Tera’s resurrection is the embodiment of this threat:

"It was all so stupendous, so mysterious, so unnecessary! The issues were so vast; the danger so strange, so unknown. Even if it should be successful, what new difficulties would it not raise…there would be some strange and awful development—something unexpected and unpredictable—before the end should be allowed to come…!”.[23]

The confirmation of Tera’s existence and her potential ability to return and invade Western civilization, shattering pre-existing beliefs about religion and science, reflects the anxieties brought on by the end of imperialism. This echoes the uncertainty of the future as the era of imperialism came to an end, and the idea of reverse colonialism became more prominent and terrifying.

Gothic horror

The Jewel of Seven Stars is part of a subgenre of Gothic fiction known as Gothic horror. First featured in Horace Walpole's The Castle of Otranto, Gothic horror combines elements of the Gothic and Romantic genres to create a pleasurably terrifying experience.[24] Frankenstein, The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, and Stoker’s Dracula are all considered landmarks of Gothic horror fiction. Though it increased in popularity in the nineteenth century, elements of Gothic horror have appeared in more contemporary works, influencing authors from Edgar Allan Poe to Stephen King. The genre is marked by supernatural occurrences, gloomy settings, violent emotions, terror, and threatening villains, all of which appear in The Jewel of Seven Stars. The villains are themselves supernatural in some way; the abundance of mummy fiction in late Victorian literature is closely linked to this genre.[25]

Style

Stoker’s writing style is often overlooked, as he is seen as more of a genre writer due to his mastery of the horror novel than a literary author. Most of his writings are still unknown; in an interview with Stoker’s grandnephew, this is attributed to the fact that "Stoker never had time to perfect his style in the numerous novels and stories he wrote…most of the rest of his product remains unreadable and inept. Some of it, in fact, is so bad that it has been mistaken for burlesque".[26]

However, scholars of Stoker’s forgotten works contest this, arguing that Stoker was much more than a genre author writing for "chills and thrills". In a review of a collection of Stoker’s lesser-known writing, critic Colin Fleming explains, "there’s no easy category to dump [Stoker] in, and the one he’s in—Scary Writer Guy—is limiting".[27] Fleming classifies Stoker’s style as Gothic as well as Modernist, pointing out Modernistic elements such as non-linear narrative and referring to his works as "collage art": a combination of voices from a variety of sources that make up a single text.[27] This idea of collage is represented in the journalistic interludes and alternating voices in The Jewel of Seven Stars; at two points, the story breaks away from Malcolm’s narration and takes on the voice of first Nicholas Van Huyn, through a retelling of his novel, and then Corbeck’s extensive story about finding Tera’s tomb.

Stoker’s style was arguably a product of his background in the theatre, working as business manager to theatre legend Henry Irving and running the Lyceum Theatre for twenty-seven years. Wynne posits that Stoker’s melodramatic tendencies were directly influenced by his knowledge of Victorian theatre, "with all its theatrics and high emotions".[28] The mysticism of the occult and the supernatural that Stoker expounds upon in The Jewel of Seven Stars, Wynne argues, was inspired by the stage "magic" and innovations in staging that allowed for illusions to be performed in the theatre: "Stoker in his fiction…[uses] illusion in the service of the supernatural".[29]

In addition to being influenced by his relationship with Irving and the theatre, Stoker’s style was also influenced by his friendship with poet Walt Whitman. According to Perry, Stoker admired the poet and often emulated his style in personal letters to Whitman, an emulation that would later appear in Stoker’s novels. Stoker’s lengthy, eloquent descriptions possess a poetic quality, and Perry argues that his characters "[speak] with a sense of rhythm, parallelism, and balance that is characteristic of Whitman".[30]

Themes

Old versus New

A major concern in The Jewel of Seven Stars is the tension between the Old World and the New in terms of progress. The late nineteenth century was a time of invention and modernization, and the novel constantly questions the power of the past in comparison to these modern technological and scientific innovations. Senf argues that "Stoker was aware of the scientific and cultural developments that were taking place around the turn of the century, that he was fascinated with technological developments…Stoker sometimes saw the future as full of infinite possibilities for improvement, [and] sometimes as totally at the mercy of primitive forces".[31] This is demonstrated in the appropriately titled chapter, "Powers—Old and New", in which Malcolm considers the consequences of Tera’s resurrection on existing British beliefs. The direction of his thoughts in this chapter, which was notably deleted from the 1912 edition, seems to indicate that ancient Egyptian society was more progressive than nineteenth-century England, both spiritually and scientifically:

"The whole possibility of the Great Experiment to which we were now pledged was based on the reality of the existence of the Old Forces which seemed to be coming in contact with the New Civilisation…If there were truth at all in the belief of Ancient Egypt then their Gods had real existence, real power, real force…If then the Old Gods held their forces, wherein was the supremacy of the new?”[23]

Malcolm realizes in this passage that the success of Tera’s resurrection will shake the fundamental Christian belief of monotheism by proving that the religious principles of the Egyptians held merit and truth. Cowed by this perjurious thought, Malcolm reflexively cuts himself off, thinking, "I dared not follow it!”.[23] However, the question of progression is immediately brought up again in Trelawny’s equally unnerving theories on science. In particular, Trelawny posits that the Egyptians had discovered electricity and radioactivity long before nineteenth-century scientists. As Hebblethwaite explains, radioactivity had been recently discovered by Pierre and Marie Curie at the time of The Jewel of Seven Stars’ publication, and "electric light was just beginning to be widely used in domestic households…throughout Stoker’s novel, there runs an underlying sense of wonder at modern man’s ability to harness the power of electricity".[32] In light of the fact that these scientific advancements were so recent, the idea that ancient Egyptians had been using this science centuries before is even more staggering.

Especially given that The Jewel of Seven Stars was published right at the turn of the twentieth century, Stoker’s implications of the power of the past call for a respect for "primitive" nineteenth-century discoveries. Hebblethwaite articulately states: "As a new century began, and Victorian became Edwardian, [the novel] counsels its readers not to utterly reject the past as archaic and non-essential—there were things of value to be learned and remembered".[33]

The New Woman

At the time of The Jewel of Seven Stars’ writing, the empowerment and assertiveness of women was on the rise. The fin-de-siecle was marked by the emergence of the “New Woman”, middle-class feminists who espoused the domestic sphere and sought social and sexual freedom, challenging the gender roles that dominated British society. Jusova explains that by "[contesting] and defamiliarizing the hegemonic Victorian definitions of gender and sexual identities, the New Woman further fueled the anxieties and fears that already circulated among the middle-class British population at the time".[34]

Stoker’s other works, most notably Dracula, are heavily critical of the New Woman, rebuking the characters' progressive sexuality, as in the case of the female vampires in Dracula: "the female vampires in Dracula are [Stoker's] way of responding to the growing equality of men and women, in particular their sexual equality. Not only does he emphasize their voluptuousness and sexual aggression and contrast their behavior to that of his chaste and sexually timid heroine but he has his male characters destroy these threatening women and reestablish a more traditional order".[35] As the New Woman became more prevalent in society, however, Stoker continued to feature independent female characters in his works, balancing an exploration of the possibility of feminine power with a patriarchal discourse: "[Stoker’s heroines] frequently display both a degree of personal assertion and a sexual precocity which at first sight distances them from the patriarchal ideal of female passivity and subservience…even though by the end of each work the suggestion is implicitly made that biological difference, the destiny invested in gender, is the most powerful force of all".[36]

This contradiction can be seen in The Jewel of Seven Stars through Margaret’s transformation; though she gains strength throughout the novel, in the end she does not survive to see a society where New Women reign. Margaret begins as a timid, submissive daughter and non-threatening love interest, but she gradually takes on the qualities of Queen Tera, becoming strong and self-sufficient. As Margaret’s feminine qualities strengthen, her male counterparts are increasingly threatened. Malcolm is continually disturbed and "quite unmanned" by Margaret’s empowerment and, as Hebblethwaite points out, "finds her newfound womanly emotionalism—'gloom and anxiety, hope, high spirits, deep depression, and apathetic aloofness'—not conducive to his own peace of mind".[37] The more Margaret embraces her freedom, the more distant she is to Malcolm, even occasionally showing outright disdain; this exemplifies what males fear will happen if women gain autonomy.

When the men in the narrative attempt to regain masculine control, they are subverted by Margaret. As Deane argues, the wrapped and veiled Victorian mummy is extremely sexualized, "a woman…who, perfectly preserved in her youthful beauty, strongly attracts the libidinous attention of modern British men".[38] In the final scene, the group of men publicly and voyeuristically unravel Tera’s corpse, which, Hebblethwaite states, is a way to humiliate the female and revert her to submission.[13] Tera’s naked, youthful body is described in great detail as the men, even Malcolm, become "more and more excited".[39] However, this attempt at reassertion is interrupted by Margaret, who demands Tera be covered and removes the body from the men’s invasive gazes. Ultimately, the men are returned to the role of observer and must await Margaret’s consent to continue, implying the uncontrollable nature of the New Woman.

The ending of the novel presents an ambiguous answer to the issue of the New Woman, one that is noticeably altered in the 1912 edition. In the 1903 version, Margaret dies, putting an end to her independence. However, it is implied by the presence of Tera’s burial robe in her place that Tera lives and escapes from her male captors, suggesting a more positive outcome for the New Woman. In stark contrast, the 1912 edition drastically revises the ending: Tera dies instead and Margaret and Malcolm are married. According to Andrew Smith, "The first ending suggests Stoker’s inability properly to control the rebellious aspects of the Female Gothic, whereas the second, as in Dracula, implies the possibility of exerting social control through marriage".[40]

Critical reception

Much like Dracula, which received very little critical attention until the late 1960s,[41] The Jewel of Seven Stars had a very underwhelming response from nineteenth-century critics. When the novel was released in 1903, critics and readers were generally left confused by the story; one review stated that readers would "curdle their blood" and "addle their brains" trying to understand "this most extraordinary story".[42] A London newspaper, The Saturday Review, was even less positive: "This book is not one to be read in a cemetery at midnight…but it does not quite thrill the reader as does the best work in this genre…It is due to Mr. Stoker to say that his wild romance is not ridiculous even if it fails to impress".[43] In Stoker’s body of work, the endings are all relatively satisfying, clear-cut, and optimistic. The ambiguous, tragic ending of The Jewel of Seven Stars left readers baffled. In the 1960s and 1970s, when critical studies of Dracula increased, more of Stoker's lesser-known work came to light, including The Jewel of Seven Stars. The novel has been examined by critics, but is seen more as a collective part of Stoker's work than an exemplary novel that stands on its own, as Dracula does.

1912 edition

When the novel was re-released in 1912, the speculative chapter 16, "Powers Old & New", had been removed. The ending was rewritten as an upbeat, straightforward conclusion wherein Tera is defeated, everyone lives, and Margaret and Malcolm get married. Until the publication of the Penguin Classics edition in 2008, which included Chapter 16 as well as both endings, the 1912 version of The Jewel of Seven Stars was the only edition available.[13] Though Harry Ludlam’s biography of Stoker states that the publishers asked for a happier and less gruesome ending, Stoker never confirmed this reason.[44] In addition, Ludlam’s explanation does not account for the removal of Chapter 16. Stoker’s own perspective on censorship in a 1908 essay indicates that he would not have consented to censorship by a publisher: "[T]he strongest controlling force of imagination is in the individual with whom it originates. No one has power to stop the workings of imagination…individual discretion is the first line of defence against such evils as may come from imagination".[45] From this statement promoting self-censorship, William Hughes constructed an argument that Stoker himself chose to revise the ending and remove Chapter 16 because it incited religious doubt and speculation that would threaten dominant religious beliefs.[46]

Adaptations

- Television

- Film

- Blood from the Mummy's Tomb (1971)

- The Awakening (1980)

- The Tomb (1986)

- Bram Stoker's Legend of the Mummy (1998)

- Video

- Legend of the Mummy (1997)

- Radio

- The Mummy (1999)

- Short stories

- Kim Newman's set of linked short stories, Seven Stars, incorporate the titular jewel into his Diogenes Club series.

References

- 1 2 "The jewel of the seven stars" (1st US ed). LC Online Catalog. Library of Congress (loc.gov). Retrieved 2016-09-16.

- ↑ "The Jewel of Seven Stars" (92pp, 1902); "The Jewel of Seven Stars" (162, 280pp, 1903). LC Online Catalog. Retrieved 2016-09-16.

- ↑ Egypt. In Britannica Online Encyclopedia. Encyclopedia Britannica Inc.

- ↑ Brier, B. (2013). Egyptomania: Our three thousand year obsession with the Land of the Pharaohs. Palgrave Macmillan.

- ↑ Patterson, J. D. (2002). Beyond Orientalism: Nineteenth century Egyptomania and Frederick Arthur Bridgman’s 'The Funeral of a Mummy'. University of Louisville.

- ↑ Luckhurst, R. (2012). The mummy’s curse: The true history of a dark fantasy. Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Bulfin, A. (2011). The fiction of Gothic Egypt and British Imperial paranoia: The curse of the Suez Canal. English Literature in Transition, 1880-1920, (54) 4, 411-443.

- ↑ Fleischhack, M. (2009). Vampires and Mummies in Victorian Gothic Fiction. Inklings: Jahrbuch für Literatur und Ästhetik, 27, 62-77. Retrieved from http://www.academia.edu

- ↑ Deane, B. (2008). Mummy fiction and the occupation of Egypt: Imperial striptease. English Literature in Transition, 1880-1920, (51) 4, 381-410. Retrieved from http://muse.jhu.edu

- ↑ Cooney, K. The woman who would be king. Lapham’s Quarterly.

- 1 2 Wilson, E. B. (2006, September). The queen who would be king. Smithsonian Magazine.

- ↑ Highfield, R. (2007, Jun. 2007). How I found Queen Hatshepsut. The Telegraph.

- 1 2 3 Hebblethwaite, K. (2008). "Introduction". The jewel of seven stars. New York, NY: Penguin Classics.

- ↑ The jewel of seven stars, p.129

- ↑ The jewel of seven stars, p. 129

- ↑ Hebblethwaite, p.xxi

- ↑ Lennon, J. (2008). Irish Orientalism: A literary and intellectual history. New York: Syracuse University Press.

- ↑ Belford, B. (2002). Bram Stoker and the man who was Dracula. Da Capo Press.

- ↑ Stoker, B. (1906). Personal reminiscences of Henry Irving. London: Heinemann.

- ↑ Hebblethwaite, p.xix

- ↑ Brantlinger, P. (1988). Rule of darkness: British literature and imperialism, 1830-1914. Cornell University Press. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org

- ↑ Brantlinger, P. (1985, Jan. 1). Imperial gothic: Atavism and the occult in the British adventure novel, 1880-1914. English Literature in Transition, 1880-1920, (28) 3, 243-252.

- 1 2 3 The jewel of seven stars, p.185

- ↑ The Gothic. (n.d.) In The Norton Anthology of English Literature: Norton Topics Online. Retrieved from http://www.wwnorton.com

- ↑ Fleischhack, M. (2009). Vampires and Mummies in Victorian Gothic Fiction. Inklings: Jahrbuch für Literatur und Ästhetik, 27, 62-77. Retrieved from http://www.academia.edu

- ↑ Muro, M. (1983, Apr. 1). Dusting off Dracula’s creator: A blood relative of Bram Stoker seeks recognition for the long-neglected Gothic novelist. Boston Globe.

- 1 2 Fleming, C. (2013). Digging up the truth about Bram Stoker. The Virginia Quarterly Review, (89) 3, 207-212. Retrieved from http://lion.chadwyck.com

- ↑ Merritt, S. M. (2013, Jul. 11). Bram Stoker, Dracula, and the Victorian Gothic stage (Book review). Diabolique Magazine.

- ↑ Wynne, C. (2013). Bram Stoker, Dracula, and the Victorian Gothic stage. Palgrave Macmillan.

- ↑ Perry, D. R. (1986). Whitman’s Influence on Stoker’s Dracula. Walt Whitman Quarterly Review, (3) 3, 29-35.

- ↑ Senf, C. A. (2002). Science and social science in Bram Stoker’s fiction. Greenwood Publishing Group.

- ↑ Hebblethwaite, p.xxix

- ↑ Hebblethwaite, xxxv

- ↑ Jusova, I. (2005). The new woman and the empire. Columbus, OH: The Ohio State University Press. Retrieved from http://ohiostatepress.org

- ↑ Senf, C. A. (2007). Rethinking the new woman in Stoker’s fiction: Looking at 'Lady Athlyne'. Journal of Dracula Studies, (7), 1-8.

- ↑ Hughes, W. (2000). Beyond Dracula: Bram Stoker’s Fiction and its Cultural Context. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

- ↑ Hebblethwaite, p.xxiv

- ↑ Deane, B. (2008). Mummy fiction and the occupation of Egypt: Imperial striptease. English Literature in Transition, 1880-1920, (51) 4, 381-410. Retrieved from http://muse.jhu.edu

- ↑ The jewel of seven stars, p.233

- ↑ Smith, A. (2004, May). Love, Freud, and the Female Gothic: Bram Stoker’s The Jewel of Seven Stars. Gothic Studies, (6)1, 87.

- ↑ Lynch, J. (Ed.). (2009). Critical insights: Dracula. Salem Press.

- ↑ (1903). Some novels of the season. The Review of Reviews, (28), p. 638.

- ↑ (1903, Dec. 19). "The Jewel of Seven Stars". Saturday review of politics, literature, science, and art. p. 768.

- ↑ Ludlam, H. (1977). A biography of Bram Stoker: Creator of Dracula. New English Library.

- ↑ Stoker, B. (1908, September). The censorship of fiction. The nineteenth century and after: A monthly review.

- ↑ Hughes, W. (1994). Profane resurrections: Bram Stoker’s self-censorship in The Jewel of Seven Stars. In A. L. Smith & V. Sage (Eds.), Gothick Origins and Innovations (132-140). Rodopi.

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- The Jewel of Seven Stars at Project Gutenberg (1912 revised ed.)

- Full text and PDF versions of the 1903 and 1912 eds. at Bram Stoker Online

-

The Jewel of Seven Stars public domain audiobook at LibriVox

The Jewel of Seven Stars public domain audiobook at LibriVox - The Jewel of Seven Stars title listing at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database