The Quatermass Xperiment

| The Quatermass Xperiment | |

|---|---|

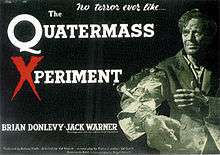

UK quad crown theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Val Guest |

| Produced by | Anthony Hinds |

| Screenplay by |

|

| Based on |

The Quatermass Experiment by Nigel Kneale |

| Starring | |

| Music by | James Bernard |

| Cinematography | Walter J. Harvey |

| Edited by | James Needs |

Production company | |

| Distributed by |

|

Release dates |

|

Running time | 82 minutes |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Budget | £42,000 |

The Quatermass Xperiment (US title: The Creeping Unknown) is a 1955 British science fiction horror film from Hammer Film Productions, based on the 1953 BBC Television serial The Quatermass Experiment written by Nigel Kneale. The film was produced by Anthony Hinds, directed by Val Guest, and stars Brian Donlevy as the eponymous Professor Bernard Quatermass. Jack Warner, Richard Wordsworth, and Margia Dean appear in supporting roles.

Three astronauts are launched into space aboard a rocket designed by Professor Quatermass, but the spacecraft returns to earth with only one occupant, Victor Carroon (Richard Wordsworth). Something has infected him during the spaceflight, and he begins mutating into an alien organism which, if it spores, will engulf the Earth and destroy humanity. When the Carroon-creature escapes from custody, Quatermass and Scotland Yard's Inspector Lomax (Jack Warner), have just hours to track it down and prevent a catastrophe.

Plot

The British Rocket Group, headed by the taciturn Professor Bernard Quatermass, launches its first manned rocket into space. Shortly thereafter, all contact is lost with the rocket and its three crew: Carroon, Reichenheim, and Green. The large rocket later returns to earth, crashing into an English country field.

Quatermass and his assistant Briscoe arrive at the scene, along with the emergency services. Opening the rocket's access hatch, the space-suited Carroon stumbles outside; inside, there is no sign of the other two crew members. Carroon is in shock, only able to say the words "Help me". He is taken to hospital while Quatermass and Briscoe investigate what happened to the rocket and its two missing crew.

It quickly becomes evident that Carroon has been altered by something he encountered in space; he can absorb any living thing with which he comes in contact. When he smashes a potted cactus in his hospital room, absorbing it, his right hand and then his arm begins to mutate. Not knowing this, Carroon's wife, Judith, hires a private investigator to break her husband out of the secured hospital. The escape is successful, but Carroon then kills and absorbs the private investigator. It does not take long for Judith to discover what her husband has become, and Carroon soon flees from his horrified wife.

Inspector Lomax of Scotland Yard initiates a manhunt to find the missing Carroon. Hiding out at the London docks, he encounters a little girl, leaving her unharmed through sheer willpower. Instead, Carroon heads for a nearby zoo where he absorbs many of the animals. By now he has become a completely mutated creature. Quatermass and Briscoe track the Carroon-creature to Westminster Abbey, where it has crawled high up on the metal scaffolding inside. From his examination of tissue samples taken from Carroon, Quatermass concludes that some kind of alien has completely taken over and will eventually release reproduction spores, endangering the entire planet. With the assistance of a television crew working at the Abbey, Quatermass succeeds in killing the Carroon-creature by electrocution.

The threat eliminated, Quatermass quickly walks through the Abbey, preoccupied by his thoughts. He ignores all who ask questions. Marsh, his other assistant, approaches and asks "What now"? Never breaking stride, Quatermass offhandedly replies, "I'll need your help. We start over again". He quickly leaves Marsh behind, walking into the London night.

Cast

- Brian Donlevy as Prof. Bernard Quatermass

- Jack Warner as Inspector Lomax

- Margia Dean as Mrs. Judith Carroon

- Richard Wordsworth as Victor Carroon

- Thora Hird as Rosemary 'Rosie' Elizabeth Wrigley

- Gordon Jackson as BBC TV Producer

- David King-Wood as Dr. Gordon Briscoe

- Harold Lang as Christie

- Lionel Jeffries as Blake

- Sam Kydd as Police Sergeant

- Jane Asher as Little Girl (uncredited)

- Basil Dignam as Sir Lionel Dean (uncredited)

- Maurice Kaufmann as Marsh (uncredited)

- Arthur Lovegrove as Sergeant Bromley (uncredited)

- Bartlett Mullins as Zookeeper (uncredited)

- Marianne Stone as Central Clinic Nurse (uncredited)

- Toke Townley as The Chemist (uncredited)

Production

The screenplay, written by Richard Landau and Val Guest, presents a heavily compressed version of the events of the original television serial. The most significant plot change occurs at the climax of the film. In the television version, Quatermass appeals to the last vestiges of the creature's humanity and convinces it to commit suicide to save the world. In the film, Quatermass kills the creature by electrocution. Nigel Kneale was critical of the changes made for the film adaptation and of the casting of Brian Donlevy, whose brusque interpretation of Quatermass was not to his liking. To make the film's plot convincing to audiences, Guest employed a high degree of realism, directing the film in a style akin to a newsreel. The film was shot on location in London, Windsor and Bray and at Hammer's Bray Studios. Carroon's transformation was effected by makeup artist Phil Leakey, who worked in conjunction with cinematographer Walter J. Harvey to accentuate Wordsworth's naturally gaunt features to give him an alien appearance. Special effects, including a model of the fully mutated creature seen at the climax, were provided by Les Bowie. The music was composed by James Bernard, the first of many scores he wrote for Hammer.

Hammer marketed the film in the United Kingdom by dropping the "E" from "Experiment" in the title to emphasise the adults-only 'X' Certificate given to the film by the British Board of Film Censors. Upon general release in 1955, the film formed one half of the highest grossing double bill in the UK. It was the first Hammer production to attract the attention of a major distributor in the US, in this case United Artists, who distributed the film under the title The Creeping Unknown. Its success led to Hammer producing an increasing number of horror films, including two sequels Quatermass 2 (1957) and Quatermass and the Pit (1967), making them synonymous with the genre. The Quatermass Xperiment is regarded as the first of these "Hammer Horrors".

Development

The Quatermass Experiment was a six-part serial broadcast by BBC Television in 1953. Written by Nigel Kneale, it was an enormous success with critics and audiences alike, later described by film historian Robert Simpson as "event television, emptying the streets and pubs".[1] Among its viewers was Hammer Films producer Anthony Hinds, who was immediately keen to buy the rights for a film version.[2] Incorporated in 1934, Hammer had developed a niche for itself making second features, many of which were adaptations of successful BBC Radio productions.[3] Hammer contacted the BBC on 24 August 1953, two days after the transmission of the final episode, to enquire about the film rights.[4] Nigel Kneale also saw the potential for a film adaptation and, at his urging, the BBC touted the scripts around a number of producers, including the Boulting Brothers and Frank Launder and Sidney Gilliat.[5] Kneale met with Sidney Gilliat to discuss the scripts but Gilliat was reluctant to buy the rights as he felt any film adaptation would inevitably receive an ‘X’ Certificate from the British Board of Film Censors (BBFC),[6] restricting admission to persons over the age of sixteen.[7] Hammer were not so reticent, deciding from the outset that they would deliberately pursue an ‘X’ Certificate.[8] Hammer's offer met some resistance within the BBC, with one executive expressing reservations that The Quatermass Experiment was not suitable material for the company, but the rights were nevertheless sold for an advance of £500.[9]

Nigel Kneale was a BBC employee at the time, which meant that his scripts were owned entirely by the BBC and he received no extra payment for the sale of the film rights.[10] This became a matter of some resentment on Kneale's part, and when his BBC contract came up for renewal he demanded and secured control over any future film rights for his work.[11] Despite this Kneale remained bitter over the affair until the BBC made an ex-gratia payment of £3,000 to him in 1967, in recognition of his creation of Quatermass.[12]

The film was co-produced by Robert L. Lippert, an American movie producer and distributor.[8] Hammer had entered into an arrangement with Lippert in 1951 under which Lippert provided finance and supplied American stars for Hammer's films and distributed them in the United States.[13] In return, Hammer's distribution arm, Exclusive Films, distributed Lippert's films in the United Kingdom.[13] Lippert's company was, in fact, a front for 20th Century Fox, whose president, Spyros Skouras, was a close friend of Lippert's.[14] Quota laws in the UK meant that US films had to have a British supporting feature, so it was in the American studios' interests to fund these features to recover a greater proportion of the box office receipts.[15]

Writing

The first draft of the screenplay was written by Richard Landau, an American who had worked on six previous Hammer productions, including Spaceways (1953), one of the company's first forays into science fiction.[16] Landau made significant changes in condensing the action to less than half the length of the original teleplay.[8] For instance, the opening thirty minutes of the television version are covered in just two minutes in the film.[17] In the process, Landau played up the horror elements of Kneale's original teleplay.[18] Aware that the film would be co-funded by American backers, Landau added a transatlantic dimension to the script: Quatermass's "British Rocket Group" became the "British-American Rocket Group" and the character of his assistant, Briscoe, was rewritten as a US Air Force flight surgeon.[8] Quatermass himself was demoted to a doctor and written much more as an action hero than the thoughtful scientist created by Nigel Kneale.[19] Some characters from the television version, such as the journalist James Fullalove, are omitted altogether.[20] Judith Carroon's role in the film version is reduced to little more than that of the stricken astronaut's anxious wife whereas in the television version she is also a prominent member of Quatermass's Rocket Group.[21] A subplot involving an extramarital affair between her and Briscoe is also left out of the film version.[22] Kneale was particularly aggravated by the dropping of the notion from his original teleplay that Carroon has absorbed not only the bodies but also the memories and the personalities of his two fellow astronauts.[16] This change leads to the most significant difference between the two versions: in the television version, Quatermass makes an appeal to the last vestiges that remain of the three astronauts absorbed by the creature and convinces it to commit suicide before it can spore whereas in the film version Quatermass kills the creature by electrocution.[23] Director Val Guest defended this change believing it was "filmically a better end to the story".[24] He also felt it unlikely that Brian Donlevy's gruff interpretation of Quatermass would lend itself to talking the creature into submission.[25]

Having fallen foul of the censors with some of their earlier films, Hammer had an informal agreement to submit scripts in advance of shooting to the BBFC for comment.[26] When the draft script for The Quatermass Xperiment was submitted, Board Secretary Arthur Watkins replied, "I must warn you at this stage that, while we accept this story in principle for the ‘X’ category, we could not certificate, even in that category, a film treatment in which the horrific element was so exaggerated as to be nauseating and revolting to adult audiences”.[27] The BBFC were particularly concerned with the violence in the scenes where Carroon escapes from hospital and with how graphic the depiction of Caroon's transformation into the alien creature would be.[28]

The script was refined further by director Val Guest, who cut 30 pages from Landau's script.[29] One of Guest's key contributions to the script was to tailor the dialogue to suit the brusque style of star Brian Donlevy.[30] With an American actor cast as Quatermass, Guest reverted Briscoe to a British character and reinstated Quatermass's title of professor.[19] Guest also adapted some sections of the script in response to the concerns of the BBFC.[29] Further stylistic changes were sought by the BBC who retained a script approval option after the sale of the rights and asked Nigel Kneale to work on their suggested changes, much to his indignation.[3] Kneale was tasked with rewriting any scenes featuring BBC announcers to match the BBC's news reporting style.[3]

Casting

Irish American actor Brian Donlevy was brought in by Robert L. Lippert to play the title role of Quatermass to provide an interest for American audiences.[31] Donlevy, in his own words, specialised in "he-men roles – rough, tough and realistic".[32] Nominated for an Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor for Beau Geste (1939),[33] he was also known for his appearances in The Great McGinty (1940) and The Glass Key (1942).[21] At the time he appeared as Quatermass his career was in decline, however.[21] Donlevy's no-nonsense portrayal of Quatermass is very different from that of Reginald Tate in the television version and was not to Nigel Kneale's liking, who said, "I may have picked Quatermass's surname out of a phone book, but his first name was carefully chosen: Bernard, after Bernard Lovell, the creator of Jodrell Bank. Pioneer, ultimate questing man. Donlevy played him as a mechanic, a creature with a completely closed mind”.[34] Responding to Kneale's criticisms, Val Guest said, "Nigel Kneale was expecting to find Quatermass like he was on television, a sensitive British scientist, not some American stomping around, but to me Donlevy gave it absolute reality".[35] By this stage in his career, Donlevy was suffering from alcoholism; it was some weeks into the shoot before Guest became aware that the flask of coffee he always carried on set was laced with brandy.[36] Guest found, however, that "Brian was all right, no problem at all once you kept him sober".[37] He reprised the role of Quatermass in Quatermass 2 (1957) but was replaced by Andrew Keir in the third film, Quatermass and the Pit (1967).[38]

Inspector Lomax was played by Jack Warner, who appeared by arrangement with the J. Arthur Rank Organisation, with whom he was contracted.[39] At the time he was best known as the star of Here Come the Huggetts (1948) and its sequels.[40] Shortly after finishing The Quatermass Xperiment, he made his first appearance on television in the role he is most associated with, as the title character in Dixon of Dock Green (1955–76).[40] Warner plays Lomax in a lighthearted fashion and there is a running joke in the film involving Lomax's futile attempts to find the time to have a shave with his electric razor.[41]

Richard Wordsworth was cast by Val Guest as the hapless Victor Carroon because "he had the right sort of face for the part".[42] He was best known at the time for his work in the theatre.[43] His performance in The Quatermass Xperiment is frequently compared with that of Boris Karloff in Frankenstein (1931).[44] Guest, aware of the risk of an actor going over the top with the part, directed Wordsworth to "hold back just a mite of what you're feeling".[45] Summing up Wordsworth's performance, film critic Bill Warren said, "All Carroon's anguish and torment are conveyed in one of the best mime performances in horror and science fiction films... A sequence in which he is riding in a car with his wife is uncanny: only the alien is visible for a long moment".[46] Wordsworth went on to appear in three more Hammer films: The Camp on Blood Island (1958), The Revenge of Frankenstein (1958) and The Curse of the Werewolf (1961).[47] He remained known predominantly as a stage actor, among other things devising and starring in a one-person show dedicated to his great-great grandfather, the poet William Wordsworth.[48]

Another American star provided by Robert L. Lippert was Margia Dean, who played Judith Carroon. A former beauty queen,[21] Dean was allegedly cast on account of her association with the 20th Century Fox president, Spyros Skouras.[13] According to executive producer Michael Carreras, "Skouras had a girlfriend who was an actress and he wanted her in pictures, but he didn't want her in pictures in America, because of the tittle-tattle or whatever, so he set it up though his friend Bob Lippert".[49] Val Guest recalled of her, "She was a sweet girl, but she couldn't act".[50] Her American accent was considered out of place in the film and so her lines were dubbed in post production.[21]

Among the other actors that appear in the film are Thora Hird, Gordon Jackson, David King-Wood, Harold Lang, Lionel Jeffries and Sam Kydd, many of whom appeared regularly in films directed by Val Guest.[51] The Quatermass Xperiment also saw an early role for Jane Asher, who plays the little girl whom Carroon encounters when he is on the run.[52]

Filming

Val Guest was hired to direct the film. He began his career co-writing comedies such as Oh, Mr Porter! (1937) and Ask a Policeman (1939) before moving into directing with Miss London Ltd. (1943).[53] His first directing job for Hammer was on Life with the Lyons (1954) and he went on to direct their first two colour features: The Men of Sherwood Forest (1954) and Break in the Circle (1954).[54] Guest had little interest in science fiction and was unenthusiastic about directing the film; he reluctantly took copies of Nigel Kneale's television scripts with him on holiday in Tangiers and only began reading them after being teased for his "ethereal" attitude by his wife, Yolande Donlan.[55] Impressed by what he read and pleased to be offered the opportunity to break away from directing comedy films, he took the job.[56] In his approach to directing the film, Guest sought to make "a slightly wild story more believable"[57] by creating a "science fact" film, shot "as though shooting a special programme for the BBC or something".[58] Influenced by Elia Kazan's Panic in the Streets (1950),[59] Guest employed a cinéma vérité style, making extensive use of hand-held camera, even on set, an unusual technique for the time which horrified several of the technicians employed on the film.[60] To inject pace and add further realism into the story, Guest directed his actors to deliver their lines rapid-fire and to overlap the dialogue.[59] A meticulous planner, he created storyboards for every shot and mounted them on a blackboard so as to brief the crew for each day's scenes.[61] As a consequence, some members of the crew found Guest's approach to be too mechanical.[62]

Principal photography began on 12 October 1954 with a night shoot at Chessington Zoo[28] and continued from 18 October 1954 into December.[63] The budget was £42,000, low even by the standards of Hammer at the time.[28] Special effects technician Les Bowie recalled, "We did Quatermass on a budget so low it wasn't a real budget. I did it for wages not as a proper effects man who gets allocated a certain budget for a movie".[64] The shots of the emergency services rushing to the rocket crash site at the beginning of the movie were filmed in the village of Bray, Berkshire, where Hammer's studios were located.[35] The scenes with the crashed rocket were shot in a corn field at Water Oakley, near Bray.[35] It was originally intended to make the crash site look more spectacular by setting fire to the field but bad weather put paid to this idea.[65] Guest used a wide-angle lens for these shots to convey a feeling of vastness to the scene.[66] Carroon's encounter with the little girl was filmed at the East India Docks in London.[67] A second unit, under cameraman Len Harris, conducted additional location shooting around London for the montage scenes of the police search for Carroon.[66] For the shot of the lights of London going out when the electricity is diverted to Westminster Abbey, an agreement was made with one of the engineers at Battersea Power Station to turn off the lights illuminating the outside of the station; however the engineer misunderstood and briefly cut all the power along the River Thames.[35] Most of the remaining location shooting was done in the Windsor area.[35] The rest of the film was shot at Hammer's Bray Studios, with the New Stage there housing the sets for the hospital and the interior of Westminster Abbey.[68] Michael Carreras had written to the Abbey seeking permission to film there but was refused.[69] The rooms of Down Place, the former country house Bray Studios were built around, were used for other scenes such as Inspector Lomax's office.[28] Art director James Elder Wills, in his final film for Hammer, made great use of the existing architecture of Down Place to enhance the effectiveness of his sets.[70]

Makeup and special effects

The work of makeup artist Phil Leakey in transforming Richard Wordsworth's Carroon into the mutating creature was a key contribution to the effectiveness of the film. Val Guest, Anthony Hinds and Leakey all agreed that the makeup should make Carroon appear pitiful rather than ugly.[71] Leakey placed a light above the actor in the makeup chair and then worked on accentuating the shadows cast by his eyebrows, nose, chin and cheekbones.[62] The makeup was a liquid rubber solution mixed with glycerine to give the impression of sweat.[72] Leakey's job was made easier by Wordsworth's natural high cheekbones and hollow temples and he also worked closely with cinematographer Walter J. Harvey to ensure the lighting in each shot emphasised Wordsworth's features.[62] Leakey also created Carroon's mutating arm. The hand was created from a cast of the hand of an arthritis victim, enlarged and exaggerated by Leakey.[73] The rest of the arm was built up using latex and rubber and, inside, had a series of plastic tubes through which fluid was pumped to give the effect of the arm swelling.[71] A large sponge-rubber prosthetic was used for a brief scene in the zoo showing Carroon's mutation had advanced further.[71] The shrivelled corpses of Carroon's victims, glimpsed from time to time in the film, were also made by Leakey.[74]

Les Bowie provided the special effects: he had made his name perfecting an improved technique for matte painting, called the delineating matte, and formed a company with Vic Margutti that specialised in matte effects.[75] Bowie provided a number of matte paintings to enhance the scale of certain key shots in the film, including the crashed rocket, the Westminster Abbey set and the shot of Quatermass walking away from the Abbey at the climax of the movie.[76] Partly because of the concerns raised by the BBFC and partly on account of the low budget, Val Guest kept the creature largely off-screen for much of the film, feeling that audiences' imaginations would fill in the blanks more effectively than he and the special effects team could deliver on-screen.[77] For the climactic scenes at Westminster Abbey, however, Bowie created a monster from tripe and rubber and photographed it against a model of the Abbey.[65] Sparks and fireworks were used for the shots of the creature being electrocuted.[78] Michael Carreras felt something was missing when he viewed the first cut of this scene: he said, "There was this great glob of something hanging about on the scaffolding. And they had put in the best music they could and put the best effects on it, but it meant nothing as far as I was concerned… absolutely nothing at all".[79] An eye was added to the model of the monster and a human scream added to the soundtrack to give the creature some semblance of humanity in its final moments.[65] Models were also used for the rocket blasting off in the final shot of the film.[80]

Music

|

Opening Credits (Excerpt)

The rising and falling three-note semitone that pervades the score. |

| Problems playing this file? See media help. | |

John Hotchkis was originally hired to compose the music but, when he fell ill, Anthony Hinds asked conductor John Hollingsworth to recommend a replacement.[81] Hollingsworth suggested James Bernard, with whom he had worked on a number of BBC radio productions.[82] Bernard sent Hinds a tape of the score of one of these productions, an adaptation of The Duchess of Malfi, and was duly hired.[83] Bernard watched the film a number of times, stopping after each reel to make notes and discuss where the music would be needed.[81] Val Guest was not involved in any of the music sessions; Anthony Hinds supervised Bernard and made the final decisions as to where the music should occur.[84] Bernard composed the music at his piano and then worked out the orchestration, which was performed by the Royal Opera House Orchestra.[85] Hollingsworth restricted the arrangement of the score to just the string and percussion sections: Bernard recalled, "I had not written for film before and had only used strings for the BBC scores, so I think that John thought it would be better to see how I got on with these two sections before letting me loose with a full orchestra".[86] The score runs to 20 minutes and uses a rising and falling three-note semitone throughout.[87] Bernard's biographer, David Huckvale, argues that Bernard's use of atonal strings to create a sense of menace predates Bernard Herrmann's score for Psycho (1960), which is usually cited as the first film to employ the technique.[88] Remarking on the effectiveness of the score, the film critic John Brosnan said, "Of prime importance, is the contribution of the soundtrack, in this case supplied by James Bernard who never wrote a more unnerving, jangly score".[42] Bernard went on to become Hammer's most prolific composer, scoring 23 Hammer films between 1955 and 1974.[89] Several cues from The Quatermass Xperiment were released on CD in 1999 by GDI Records on a compilation titled The Quatermass Film Music Collection.[90]

Reception

Cinema release

As expected, The Quatermass Xperiment received an ‘X’ Certificate from the BBFC,[63] restricting admission to persons over the age of sixteen.[7] It was only the twelfth film to receive the certificate since its introduction in 1951.[91] Whereas most other studios were nervous of this new certificate, Hammer, who had noticed the success of the similarly ‘X’-rated Les Diaboliques (1954),[92] chose to exploit it by dropping the "E" from "Experiment" in the title of the film.[49] "X is not an unknown quantity" was the tagline Exclusive Films used to sell the picture to cinema managers, urging them to "Xploit the Xcitement" of the film.[93] On subsequent re-releases, the film reverted to the title The Quatermass Experiment.[49]

The Quatermass Xperiment premièred on 26 August 1955 at the London Pavilion on Piccadilly Circus.[94] The supporting feature was The Eric Winstone Band Show.[49] It performed extremely well during its West End run, taking £3,500 a week at the box office.[79] Timed to coincide with the broadcast of the television sequel, Quatermass II,[95] the film went on general release in the United Kingdom on 20 November 1955 in a double bill with the French film Rififi.[96] This became the most successful double bill release of 1955 in the UK.[97] In some parts of the UK, the Watch Committees of local councils demanded certain scenes, mainly close-up shots of Carroon's victims, be removed before allowing the film to be exhibited in their jurisdictions.[74]

In the United States, Robert L. Lippert attempted to interest Columbia Pictures in distributing the film but they felt it would be competition for their own production, It Came From Beneath The Sea, which was on release at the time.[95] Because Quatermass was unknown in the US, Lippert had renamed the film Shock!. [74] Unable to secure a sale, he retitled it again, this time to The Creeping Unknown.[74] United Artists eventually acquired the distribution rights in March 1956 for a fee of $125,000.[95] The Creeping Unknown was packaged in a double bill with a Gothic horror movie called The Black Sleep, starring Basil Rathbone, Lon Chaney, Jr. and Bela Lugosi.[49] Four minutes, mainly of expository material, were cut from the runtime of the film.[98] It opened in US theatres in June 1956 and was so successful that United Artists offered to part-fund a sequel.[99] According to a report in Variety, published on 6 November 1956, a nine-year-old boy died of a ruptured artery at a cinema in Oak Park, Illinois during a showing of this double bill.[49] The Guinness Book of Records subsequently recorded the incident as the only known case of an audience member dying of fright while watching a horror film.[100]

Critical response

The Times newspaper gave the film a generally favourable assessment: its critic wrote, "Mr. Val Guest, the director, certainly knows his business when it comes to providing the more horrid brand of thrills... The first part of this particular film is well up to standard. Mr. Brian Donlevy, as the American scientist responsible for the experiment, is a little brusque in his treatment of British institutions but he is clearly a man who knows what he is doing. Mr. Jack Warner, representing Scotland Yard, is indeed a comfort to have at hand when Things are on the rampage."[101] Positive reviews also came from Peter Burnup in the News of the World, who found that "with the added benefit of bluff, boisterous Brian Donlevy… all earnest addicts of science fiction will undoubtedly love every minute of it"[102] while the reviewer in The Manchester Guardian praised "a narrative style that quite neatly combines the horrific and the factual"[102] and Today's Cinema called it "one of the best essays in science fiction to date"[49] Film historian Bruce G. Hallenbeck notes a degree of national pride in some of the positive reviews.[74] For instance, Paul Dehn in the News Chronicle said, "This is the best and nastiest horror film I have seen since the War. How jolly that it is also British!".[49] Similarly, William Whitebait in the New Statesman, who found the film to be "better than either War of the Worlds or Them!",[103] also called for "a couple of cheers for the reassurance that British films can still, once in a while, come quick".[104]

On a less positive note, Frank Jackson of Reynolds News quipped "That TV pseudo-science shocker The Quatermass Xperiment has been filmed and quitermess they've made of it too",[103] before slating the film as "82 minutes of sick-making twaddle".[102] The horror content of the film was mentioned in several reviews: Patrick Gibbs of the Daily Telegraph said the film "gives the impression that it originated in the strip of some horror comic. It remains very horrid and not quite coherent"[102] while the reviewer in the Daily Mirror found the film to be "a real chiller thriller but not for the kids"[102] and Dilys Powell of The Sunday Times found the film "exciting but distinctly nauseating".[102] Another unimpressed critic was François Truffaut, who wrote in Cahiers du cinéma that "This one is very, very bad, far from the small pleasure we get, for example, from the innocent science fiction films signed by the American Jack Arnold... The subject could have been turned into a good film, not lacking in spice; with a bit of imagination... None of this is in this sadly English film”.[105]

Upon its release in the United States Variety praised the film as an "extravagant piece of science fiction. Despite its obvious horror angles, production is crammed with incident and suspense".[74] According to Hallenbeck, many US critics found Brian Donlevy's gruff Quatermass a breath of fresh air from the earnest hero scientists of American science fiction films, such as Gene Barry's character in War of the Worlds.[74]

Other US trade reviews were mixed. Harrison's Reports felt, "the story is, of course, quite fantastic but it has enough horrific ingredients to go over with those who enjoy scary doings."[106] Film Bulletin was not impressed. "Its strong point is an eerie atmosphere . . . but fails to build the suspense essential in this kind of film . . . Val Guest's direction is heavy with cliches."[107]

Among the critics and film historians who have reviewed The Quatermass Xperiment in the years since it release have been John Baxter who said, in Science Fiction in the Cinema (1970), "In its time, The Quatermass Experiment was a pioneering sf film... Brian Donlevy was stiff but convincing... Much of the film is saved, however, by Richard Wordsworth... one of the finest such performances since Karloff's triumphs of the Thirties.”[108] This view was echoed by John Brosnan in The Primal Screen (1991): "One of the best of all alien possession movies",[109] he wrote, "Not since Boris Karloff as Frankenstein's monster has an actor managed to create such a memorable, and sympathetic, monster out of mime alone".[42] Bill Warren in Keep Watching The Skies! (1982) found that "the buildup is slightly too long and too careful"[110] but also said, "It's an intelligent, taut and well-directed thriller; it showcases Nigel Kneale's ideas well; it's scary and exciting. It was made by people who cared about what they were doing, who were making entertainment for adults. It is still one of the best alien invasion films".[111] Steve Chibnall, writing for the British Film Institute's Screenonline, describes The Quatermass Xperiment as "one of the high points of British SF/horror cinema."[112] The horror fiction writer Stephen King praised the film as one of his favourite horror movies from between 1950 and 1980 in his non-fiction book Danse Macabre (1991).[113] The film director John Carpenter, who later collaborated with Nigel Kneale on the film Halloween III: Season of the Witch (1982), has claimed that The Quatermass Xperiment "had an enormous, enormous impact on me – and it continues to be one of my all-time favourite science-fiction movies."[114]

Legacy

The success of The Quatermass Xperiment came at an opportune time for Hammer. By 1955 the deal with Robert L. Lippert had expired and the company produced just one feature film that year, Women Without Men.[115] Many of the independent cinemas that provided the market for Hammer's films in the UK were struggling in the face of competition from television and faced closure.[115] The Quatermass Xperiment gave Hammer a much needed box office hit and was also the first film to bring the company to the attention of a major film distributor, in this case United Artists.[116] From this point onward, Hammer was increasingly able to deal directly with the major distributors and no longer needed intermediaries like Lippert.[116] This ultimately spelt the end for Exclusive Films, Hammer's own distribution company, which was wound down in the late 1950s.[117]

Hammer quickly sought to capitalise on its good fortune with a sequel. Staff member Jimmy Sangster pitched a story about a monster emerging from the Earth's core.[118] However, when the company asked Nigel Kneale for permission to use the character of Quatermass, he refused, not wanting to lose control of his creation.[119] Nevertheless, the film went ahead, as X the Unknown (1956), again capitalising on the 'X' Certificate in its title and featuring a newly created scientist character, very much in the Quatermass mould, played by Dean Jagger.[120] Quatermass did eventually return to cinema screens in Quatermass 2 (1957) and Quatermass and the Pit (1967), both of which had screenplays written by Nigel Kneale and based on serials originally written by him and presented by BBC Television.[121] Rival British film companies also tried to cash in with science fiction films of their own, including Satellite in the Sky, The Gamma People and Fire Maidens from Outer Space (all 1956).[122]

The Quatermass Xperiment was Hammer's first film to be adapted from a television drama.[123] Market research carried out by the company showed that it was the horror aspect of the film, rather than the science fiction, that most appealed to audiences.[124] Three of the four films Hammer made in 1956 were horror films: X the Unknown, Quatermass 2 and The Curse of Frankenstein.[125] The enormous success of the latter of these cemented Hammer's reputation for horror and the company became synonymous with the genre.[126] Michael Carreras later said, "The film that must take all the credit for the whole Hammer series of horror films was really The Quatermass Xperiment".[127]

Video releases

The Quatermass Xperiment was released in 2003 by DD Video on Region 2 DVD. It contained a number of extra features including a commentary by director Val Guest and Hammer historian Marcus Hearn, as well as an interview with Val Guest, an original trailer, and a production booklet written by Marcus Hearn and Jonathan Rigby.[128] A Region 1 made-on-demand DVD-R, sourced from a high-definition master, was released in 2011[129] by MGM. The film had been previously released on VHS cassette and LaserDisc.

In other media

The film was adapted into a 16-page comic strip published in two parts in the March–April 1977 and June 1977 issues of the magazine The House of Hammer (volume 1, issue #'s 8 and 9, published by General Book Distribution). It was drawn by Brian Lewis from a script by Les Lilley and Ben Aldrich. The cover of issue 9 featured a painting by Lewis of Professor Quatermass.

References

Notes

- ↑ BBC News Online 1 November 2006.

- ↑ Hearn & Rigby 2003, p. 8.

- 1 2 3 Murray 2006, p. 43.

- ↑ Pixley 2005, p. 14.

- ↑ Murray 2006, p. 36.

- ↑ Murray 2006, pp. 36–37.

- 1 2 Brooke 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 Hearn & Rigby 2003, p. 9.

- ↑ Hearn 2011, p. 9.

- ↑ Murray 2006, p. 37.

- ↑ Murray 2006, p. 48.

- ↑ Murray 2006, p. 98.

- 1 2 3 Kinsey 2010, p. 20.

- ↑ Meikle 2009, p. 10.

- ↑ Hearn & Barnes 2007, p. 10.

- 1 2 Kinsey 2002, p. 32.

- ↑ Guest & Hearn 2003, 02:26–02:45.

- ↑ Hallenbeck 2011, p. 66.

- 1 2 Hearn 1999, p. 5.

- ↑ Murray 2006, p. 44.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Hallenbeck 2011, p. 68.

- ↑ Warren 1982, p. 250.

- ↑ Hearn & Rigby 2003, p. 10.

- ↑ Guest & Hearn 2003, 1:14:28–1:14:35.

- ↑ Guest & Hearn 2003, 1:14:55–1:15:12.

- ↑ Kinsey 2010, p. 57.

- ↑ Kinsey 2002, p. 33.

- 1 2 3 4 Kinsey 2002, p. 34.

- 1 2 Hearn & Rigby 2003, p. 11.

- ↑ Hearn & Rigby 2003, p. 17.

- ↑ Meikle 2009, p. 18.

- ↑ Schlossheimer 2002, p. 170.

- ↑ Schlossheimer 2002, p. 165.

- ↑ Hearn & Rigby 2003, p. 7.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Kinsey 2002, p. 35.

- ↑ Guest & Hearn 2003, 09:14–09:55.

- ↑ Kinsey 2010, p. 128.

- ↑ Hearn & Barnes 2007, pp. 20, 117.

- ↑ Kinsey 2002, p. 36.

- 1 2 Hearn & Rigby 2003, p. 14.

- ↑ Guest & Hearn 2003, 54:27–55:03.

- 1 2 3 Brosnan 1991, p. 74.

- ↑ Hearn & Rigby 2003, p. 15.

- ↑ See, for example, Baxter 1970, p. 96; Warren 1982, p. 253; Brosnan 1991, p. 74.

- ↑ Guest & Hearn 2003, 40:51–41:26.

- ↑ Warren 1982, p. 253.

- ↑ Meikle 2009, pp. 229–264.

- ↑ Benedick 1993.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Hearn & Barnes 2007, p. 17.

- ↑ Weaver 2003, p. 101.

- ↑ Hearn, Rigby & 2003 p-14.

- ↑ Weaver 2003, p. 106.

- ↑ Kinsey 2010, p. 127.

- ↑ Hearn & Barnes 2007, p. 27.

- ↑ Weaver 2003, p. 100.

- ↑ Guest & Hearn 2003, 35:01–35:45.

- ↑ Guest & Hearn 2003, 05:01–05:05.

- ↑ Guest 2003, 04:00–04:29.

- 1 2 Weaver 2003, p. 103.

- ↑ Guest 2003, 04:29–04:48.

- ↑ Guest & Hearn 2003, 59:58–1:01:09.

- 1 2 3 Kinsey 2010, p. 309.

- 1 2 Hearn & Barnes 2007, p. 16.

- ↑ Brosnan 1991, p. 75.

- 1 2 3 Kinsey 2002, p. 37.

- 1 2 Meikle 2009, p. 22.

- ↑ Guest & Hearn 2003, 51:11–52:27.

- ↑ Kinsey 2010, p. 43.

- ↑ Hearn & Rigby 2002, p. 10.

- ↑ Edie 2010, p. 82.

- 1 2 3 Johnson 1996, p. 146.

- ↑ Johnson 1996, p. 145.

- ↑ Kinsey 2010, p. 310.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Hallenbeck 2011, p. 75.

- ↑ Kinsey 2010, pp. 414–415.

- ↑ Meikle 2009, pp. 22–23.

- ↑ Guest & Hearn 2003, 1:01:23–1:02:21.

- ↑ Kinsey 2010, p. 415.

- 1 2 Meikle 2009, p. 24.

- ↑ Kinsey 2010, p. 426.

- 1 2 Kinsey 2010, p. 404.

- ↑ Mansell 1999, p. 15.

- ↑ Huckvale 1999, p. 46.

- ↑ Guest & Hearn 2003, 44:03–44:36.

- ↑ Huckvale 2006, pp. 46–49.

- ↑ Mansell 1999, p. 16.

- ↑ Huckvale 2006, pp. 49, 53.

- ↑ Huckvale 2006, p. 49.

- ↑ Mansell 1999, pp. 15–16.

- ↑ Soundtrack Collector 2012.

- ↑ Meikle 2009, p. 20.

- ↑ Bansak 2003, p. 499.

- ↑ Hearn 2011, p. 8.

- ↑ Kinsey 2003, p. 39.

- 1 2 3 Meikle 2009, p. 26.

- ↑ Hearn & Rigby 2003, p. 19.

- ↑ The Times 15 December 1955.

- ↑ Hallenbeck 2011, p. 76.

- ↑ Meikle 2009, p. 27.

- ↑ Hammer Films 2012.

- ↑ The Times 29 August 1955.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Hearn & Rigby 2003, p. 18.

- 1 2 Kinsey 2002, p. 39.

- ↑ Hearn & Rigby 2003, pp. 18–19.

- ↑ Dixon 1983, pp. 79–80.

- ↑ "Creeping Unknown". archive.org. Harrison's Reports. Retrieved 18 August 2015.

- ↑ "Creeping Unknown". archive.org. Film Bulletin Company. Retrieved 18 August 2015.

- ↑ Baxter 1970, p. 96.

- ↑ Brosnan 1991, p. 72.

- ↑ Warren 1982, p. 252.

- ↑ Warren 1982, p. 254.

- ↑ Chibnall 2011.

- ↑ Murray 2006, p. 153.

- ↑ Murray 2006, p. 154.

- 1 2 Meikle 2009, p. 19.

- 1 2 Hearn & Barnes 2007, p. 13.

- ↑ Hearn & Barnes 2007, p. 14.

- ↑ Kinsey 2002, p. 40.

- ↑ Kinsey 2010, p. 108.

- ↑ Hearn & Barnes 2007, pp. 18–19.

- ↑ Kinsey 2010, pp. 108–109.

- ↑ Hallenbeck 2011, pp. 77–78.

- ↑ Bould et al. 2009, p. 123.

- ↑ Dixon 2010, pp. 87–88.

- ↑ Kinsey 2002, p. 41.

- ↑ Meikle 2009, p. xiii.

- ↑ Meikle 2009, p. 1.

- ↑ Galbraith IV 2004.

- ↑ Erickson 2011.

Bibliography

Books

- Bansak, Edmund G. (2003). Fearing The Dark: The Val Lewton Career. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-1709-4.

- Baxter, John (1970). Science Fiction in the Cinema. London/New York: The Tantivy Press/A.S. Barnes & Co. ISBN 0-302-00476-9.

- Bould, Mark; Butler, Andrew M.; Roberts, Adam; Vint, Sherryl (2009). Fifty Key Figures in Science Fiction. Routledge Key Guides. Oxford: Routledge. ISBN 0-203-87470-6. Retrieved 4 February 2012.

- Brosnan, John (1991). The Primal Screen. A History of Science Fiction Film. London: Orbit. ISBN 0-356-20222-4.

- Dixon, Wheeler Winston (1983). The Early Film Criticism of François Truffaut. Bloomington and Indianapolis, Indiana: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-31807-7. Retrieved 31 January 2012.

- Dixon, Wheeler Winston (2010). A History of Horror. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-0-8135-4796-1. Retrieved 27 December 2011.

- Edie, Laurie N. (2010). British Film Design: A History. London: I. B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-84885-107-8. Retrieved 31 January 2012.

- Hallenbeck, Bruce G. (2011). Hammer Fantasy & Sci-Fi. British Cult Cinema. Bristol: Hemlock Books. ISBN 978-0-9557774-4-8.

- Hearn, Marcus; Barnes, Alan (2007) [1997]. The Hammer Story. The Authorised History of Hammer Films (2nd ed.). London: Titan Books. ISBN 978-1-84576-185-1.

- Hearn, Marcus (2011). The Hammer Vault: Treasures from the archive of Hammer Films. London: Titan Books. ISBN 978-0-85768-117-1.

- Huckvale, David (2006). James Bernard, Composer to Count Dracula: A critical biography. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. ISBN 0-7864-2302-1. Retrieved 28 December 2011.

- Johnson, John "J. J." (1996). Cheap Tricks and Class Acts: Special effects, makeup and stunts from the films of the fantastic fifties. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. ISBN 0-7864-0093-5. Retrieved 1 January 2012.

- Kinsey, Wayne (2002). Hammer Films. The Bray Studio Years. London: Reynolds & Hearn. ISBN 978-1-903111-44-4.

- Kinsey, Wayne (2010). Hammer Films: The Unsung Heroes. Sheffield: Tomahawk Press. ISBN 978-0-9557670-2-9.

- Meikle, Denis (2009). A History of Horrors: The rise and fall of the house of Hammer (Revised ed.). Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-6354-5.

- Murray, Andy (2006). Into The Unknown: The Fantastic Life of Nigel Kneale. London: Headpress. ISBN 1-900486-50-4.

- Schlossheimer, Michael (2002). Gunmen and Gangsters: Profiles of nine actors who played memorable screen tough guys. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. ISBN 0-7864-0989-4. Retrieved 28 December 2011.

- Warren, Bill (1982). Keep Watching The Skies! American Science Fiction Movies of the Fifties. Volume I: 1950–1957. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland Classics. ISBN 0-7864-0479-5.

- Weaver, Tom (2003). Double Feature Creature Attack: A monster merger of two more volumes of classic interviews. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. ISBN 0-7864-1366-2. Retrieved 28 December 2011.

CD and DVD liner notes and booklets

- Hearn, Marcus (1999). "Hammer's Quatermass Trilogy". The Quatermass Film Music Collection (CD liner). Various Artists. London: GDI Records. GDICD008.

- Hearn, Marcus; Rigby, Jonathan (2003). "Viewing Notes". The Quatermass Xperiment (DVD (booklet)). London: DD Video. DD06157.

- Mansell, James (1999). "James Bernard – The Quatermass Xperiment, Quatermass 2". The Quatermass Film Music Collection (CD liner). Various Artists. London: GDI Records. GDICD008.

- Pixley, Andrew (2005). "Viewing Notes". The Quatermass Collection (DVD (booklet)). London: BBC Worldwide. BBCDVD1478.

DVD commentaries and interviews

- Guest, Val; Hearn, Marcus (2003). "Audio commentary". The Quatermass Xperiment (DVD (Extra)). London: DD Video. DD06157.

- "Interview with Val Guest". The Quatermass Xperiment (DVD (Extra)). London: DD Video. 2003. DD06157.

Newspaper articles

- Benedick, Adam (29 November 1993). "Obituary: Richard Wordsworth". The Independent. London. Retrieved 28 December 2011.

- "Profitable Films: British Successes". The Times. 15 December 1955. p. 5.

- "Back to the Moulin Rouge: Jean Renoir's New Film". The Times. 29 August 1955. p. 10.

Online

- Brooke, Michael (2011). "The X Certificate". Screenonline. London: British Film Institute. Retrieved 27 December 2011.

- Chibnall, Steve (2011). "Guest, Val (1911–2006)". Screenonline. London: British Film Institute. Retrieved 27 December 2011.

- Erickson, Glenn (2011). "The Quatermass Xperiment Review". DVD Savant. Retrieved 3 January 2012.

- Galbraith IV, Stuart (2004). "The Quatermass Xperiment (Region 2)". DVD Talk. Retrieved 3 January 2012.

- "Quatermass creator dies, aged 84". BBC News Online. 1 November 2006. Retrieved 27 December 2011.

- "The Quatermass Xperiment". Hammer Films. Exclusive Media Group. 2012. Retrieved 4 February 2012.

- "Quatermass Film Music Collection, The". Soundtrack Collector. 2012. Retrieved 2 January 2012.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: The Quatermass Xperiment |

- The Quatermass Xperiment at the Internet Movie Database

- The Quatermass Xperiment at AllMovie

- The Quatermass Xperiment at Rotten Tomatoes

- The Quatermass Xperiment at Hammer Films

- The Quatermass Xperiment at the British Film Institute's Screenonline

- The Quatermass Xperiment at The Quatermass Home Page

- The Quatermass Trilogy – A Controlled Paranoia

- Quatermass.org.uk – Nigel Kneale & Quatermass Appreciation Site

- The Creeping Unknown at Trailers From Hell