The Sorcerer

.jpg)

The Sorcerer is a two-act comic opera, with a libretto by W. S. Gilbert and music by Arthur Sullivan. It was the British duo's third operatic collaboration. The plot of The Sorcerer is based on a Christmas story, An Elixir of Love, that Gilbert wrote for The Graphic magazine in 1876. A young man, Alexis, is obsessed with idea of love levelling all ranks and social distinctions. To promote his beliefs, he invites the proprietor of J. W. Wells & Co., Family Sorcerers, to brew a love potion. This causes everyone in the village to fall in love with the first person they see and results in the pairing of comically mismatched couples. In the end, Wells must sacrifice his life to break the spell.

The opera opened on 17 November 1877 at the Opera Comique in London, where it ran for 178 performances. It was considered a success by the standards of that time and encouraged the collaborators to write their next opera, H.M.S. Pinafore. The Sorcerer was revised for an 1884 revival, and it is in that version that it is usually performed today. The Sorcerer was the first Savoy opera for which the author and composer had nearly total control over the production and the selection of cast. Several of the actors chosen went on to create principal roles in most of the later Gilbert and Sullivan operas. It was their first opera to use all the major character types and typical range of songs that would appear in their later collaborations, such as comic duets, a patter song, a contrapuntal double chorus, a tenor and soprano love duet, a soprano showpiece and so forth.

The modest success of The Sorcerer was overshadowed by the extraordinary popularity of Gilbert and Sullivan's later collaborations, and the opera remains one of the team's less popular ones. The satire in the piece concerns Victorian-era class distinctions and operatic conventions with which modern audiences are less familiar. Nevertheless, the opera was important to the development of the Gilbert and Sullivan collaboration and is still regularly played.

Background

In 1871, W. S. Gilbert and Arthur Sullivan had written Thespis, an extravaganza for the Gaiety Theatre's holiday season that did not lead immediately to any further collaboration.[1] Three years later, in 1875, talent agent and producer Richard D'Oyly Carte was managing the Royalty Theatre, and he needed a short opera to be played as an afterpiece to Jacques Offenbach's La Périchole.[2] Carte was able to bring Gilbert and Sullivan together again to write the one-act piece, called Trial by Jury, which became a surprise hit.[3][4] The piece was witty, tuneful and very "English", in contrast to the bawdy burlesques and adaptations of French operettas that dominated the London musical stage at that time.[5] Trial by Jury proved even more popular than La Périchole,[6] becoming an unexpected hit, touring extensively[7] and enjoying revivals and a world tour.[8]

After the success of Trial by Jury, several producers attempted to reunite Gilbert and Sullivan, but difficulties arose. Plans for a collaboration for Carl Rosa in 1875 fell through because Gilbert was too busy with other projects,[9][10] and an attempted Christmas 1875 revival of Thespis by Richard D'Oyly Carte failed when the financiers backed out.[9][11] Gilbert and Sullivan continued their separate careers, though both continued writing light opera.[12] Finally, in 1877, Carte organised a syndicate of four financiers and formed the Comedy Opera Company, capable of producing a full-length work.[13] By July 1877, Gilbert and Sullivan were under contract to produce a two-act opera.[14] Gilbert expanded on his own short story that he had written the previous year for The Graphic, "An Elixir of Love,"[15][16] creating a plot about a magic love potion that – as often occurs in opera – causes everyone to fall in love with the wrong partner.[17]

Now backed by a company dedicated to their work, Gilbert, Sullivan and Carte were able to select their own cast, instead of using the players under contract to the theatre where the work was produced, as had been the case with their earlier works. They chose talented actors, most of whom were not well-known stars; and so did not command high fees, and whom they felt they could mould to their own style. Then, they tailored their work to the particular abilities of these performers.[18] Carte approached Mrs Howard Paul to play the role of Lady Sangazure in the new opera. Mr and Mrs Howard Paul had operated a small touring company booked by Carte's agency for many years, but the couple had recently separated.[19] She conditioned her acceptance of the part on the casting of her 24-year-old protege, Rutland Barrington. When Barrington auditioned before W. S. Gilbert, the young actor questioned his own suitability for comic opera, but Gilbert, who required that his actors play their sometimes-absurd lines in all earnestness, explained the casting choice: "He's a staid, solid swine, and that's what I want."[20] Barrington was given the role of Dr Daly, the vicar, which was his first starring role on the London stage.[21]

For the character role of Mrs. Partlet, they chose Harriett Everard, an actress who had worked with Gilbert before. Carte's agency supplied additional singers, including Alice May (Aline), Giulia Warwick (Constance), and Richard Temple (Sir Marmaduke).[22] Finally, in early November 1877, the last role, that of the title character, John Wellington Wells, was filled by comedian George Grossmith. Grossmith had appeared in charity performances of Trial by Jury, where both Sullivan and Gilbert had seen him[23] (indeed, Gilbert had directed one such performance, in which Grossmith played the judge),[24] and Gilbert had earlier commented favourably on his performance in Tom Robertson's Society at the Gallery of Illustration.[25] After singing for Sullivan, upon meeting Gilbert, Grossmith wondered aloud if the role shouldn't be played by "a fine man with a fine voice". Gilbert replied, "No, that is just what we don't want."[24][26]

The Sorcerer was not the only piece on which either Gilbert or Sullivan were working at that time. Gilbert was completing Engaged, a "farcical comedy", which opened on 3 October 1877. He also was sorting out the problems with The Ne'er-do-Weel, a piece he wrote for Edward Sothern. Meanwhile, Sullivan was writing the incidental music to Henry VIII; only after its premiere on 28 August did he begin working on The Sorcerer.[27] The opening was originally scheduled for 1 November 1877; however, the first rehearsals took place on 27 October, and the part of J. W. Wells was filled only by that time.[25] The Sorcerer finally opened at Opera Comique on 17 November 1877.[28]

Roles

_and_Lady_Sangazure_(Mrs._Howard_Paul)_in_The_Sorceror%2C_1877.jpg)

- Sir Marmaduke Pointdextre, an Elderly Baronet (bass-baritone)

- Alexis, of the Grenadier Guards, his son (tenor)

- Dr Daly, Vicar of Ploverleigh (lyric baritone)

- Notary (bass)

- John Wellington Wells, of J. W. Wells & Co., Family Sorcerers (comic baritone)

- Lady Sangazure, a Lady of Ancient Lineage (contralto)

- Aline, her Daughter, betrothed to Alexis (soprano)

- Mrs. Partlet, a Pew Opener (contralto)

- Constance, her Daughter (soprano (1877) or mezzo-soprano or soprano (1884))

- Hercules (speaking role)

- Chorus of villagers

- Note: In the 1877 production, Constance was played by a soprano, Giulia Warwick. Parts of the role were lowered in 1884 for mezzo-soprano Jessie Bond.[29]

Synopsis

Act I

The villagers of Ploverleigh are preparing to celebrate the betrothal of Alexis Pointdextre, the son of the local baronet, and the blue-blooded Aline Sangazure ("Ring forth, ye bells"). Only a young village maiden named Constance Partlet seems unwilling to join in the happy mood, and we learn as she tells her mother that she is secretly in love with the local vicar, Dr Daly ("When he is here, I sigh with pleasure"); and the cleric himself promptly soliloquises that he has been unlucky in love ("The air is charged with amatory numbers"). However, despite Mrs. Partlet's best attempts at matchmaking, the middle-aged Dr Daly seems unable to conceive that a young girl like Constance would be interested in him.

Alexis and Aline arrive ("With heart and with voice"), and it soon becomes clear that his widower father Sir Marmaduke and her widowed mother Lady Sangazure are concealing long-held feelings for one another, which propriety however demands remain hidden ("Welcome joy, adieu to sadness"). The betrothal ceremony is carried out, and left alone together Alexis reveals to his fiancée his plans for practical implementation of his principle that love should unite all classes and ranks ("Love feeds on many kinds of food, I know"). He has invited a representative from a respectable London firm of sorcerers to Ploverleigh ("My name is John Wellington Wells"). Aline has misgivings about hiring a real sorcerer. Nevertheless, Alexis instructs Wells to prepare a batch of love potion, sufficient to affect the entire village, except that it must have no effect on married people.

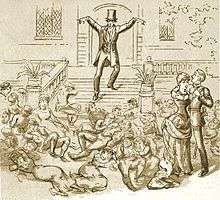

Wells mixes the potion, assisted by sprites, fiends, imps, demons, ghosts and other fearsome magical beings in an incantation ("Sprites of earth and air"). The village gathers for the wedding feast ("Now to the Banquet we Press"), and the potion is added to a teapot. All of the villagers, save Alexis, Aline and Wells, drink it and, after experiencing some hallucinations ("Oh, marvellous illusion"), they fall unconscious.

Act II

At midnight that night ("'Tis twelve, I think"), the villagers awake and, under the influence of the potion, each falls in love with the first person of the opposite sex that they see ("Why, where be Oi"). All of the matches thus made are highly and comically unsuitable; Constance, for example, loves the ancient notary who performed the betrothal ("Dear friends, take pity on my lot"). However, Alexis is pleased with the results, and now asserts that he and Aline should drink the potion themselves to seal their own love. Aline is hurt by his lack of trust and refuses, offending him ("Thou hast the power thy vaunted love"). Alexis is distracted, however, by the revelation of his upper-class father having fallen for the lower-class Mrs Partlet, but he determines to make the best of this union ("I rejoice that it's decided").

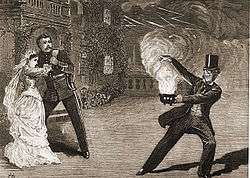

Wells, meanwhile, is regretting the results that his magic has caused, and regrets them still more when the fearsome Lady Sangazure fixes on him as the object of her affections ("Oh, I have wrought much evil with my spells"). Aline decides to yield to Alexis' persuasion and drinks the potion without telling Alexis. Upon awaking, she inadvertently meets Dr Daly first and falls in love with him ("Oh, joyous boon"). Alexis desperately appeals to Wells as to how the effects of the spell can be reversed. It turns out that this requires that either Alexis or Wells himself yield up his life to Ahrimanes. The people of Ploverleigh rally against the outsider from London and Wells, resignedly, bids farewell and is swallowed up by the underworld in a burst of flames ("Or he or I must die"). The spell broken, the villagers pair off according to their true feelings, and celebrate with another feast (reprise of "Now to the banquet we press").

Musical numbers

- Overture (includes "With heart and with voice", "When he is here", "Dear friends, take pity on my lot", and "My name is John Wellington Wells")

Act I

- 1. "Ring forth ye bells" (Double Chorus)

- 2. "Constance, my daughter, why this strange depression?" (Mrs. Partlet and Constance)

- 2a. "When he is here" (Constance)

- 3. "The air is charged with amatory numbers" (Dr Daly)

- 3a. "Time was when Love and I were well acquainted" (Dr Daly)

- 4. "Sir Marmaduke, my dear young friend Alexis" (Sir Marmaduke, Dr Daly, and Alexis)

- 4a. (Dance)

- 5. "With heart and with voice" (Chorus of Girls)

- 6. "My kindly friends" (Aline)

- 6a. "Happy young heart" (Aline)

- 7. "My child, I join in these congratulations" (Lady Sangazure)

- 8. "With heart and with voice" (Chorus of Men)

- 9. "Welcome, joy!" (Lady Sangazure and Sir Marmaduke)

- 10. "All is prepared" (Aline, Alexis, Notary, and Chorus)

- 10a."With heart and with voice" (Double Chorus)

- 11. "Love feeds on many kinds of food" (Alexis)

- 12. "My name is John Wellington Wells" (Mr. Wells)

- 13. "Sprites of earth and air" (Aline, Alexis, Mr. Wells, and Chorus)

- 14. Act I Finale (Ensemble)

- "Now to the banquet we press"

- The Tea-Cup Brindisi ("Eat, drink and be gay")

- "Oh love, true love"

- "Oh marvellous illusion"

- Tea-Cup Brindisi reprise – 1877 version only

Act II

- 15. "Happy are we in our loving frivolity" (Chorus) – 1877 version only

- 15. "'Tis twelve, I think" and "Why, where be Oi?... If you'll marry me" (Aline, Alexis, Mr. Wells, and Chorus) – 1884 version

- 16. "Dear friends, take pity on my lot" (Constance, Notary, Aline, Alexis, and Chorus)

- 17. "Thou hast the pow'r thy vaunted love" (Alexis)

- 18. "I rejoice that it's decided" (Aline, Mrs. Partlet, Alexis, Dr Daly, and Sir Marmaduke)

- 19. "Oh, I have wrought much evil with my spells" (Lady Sangazure and Mr. Wells)

- 20. "Alexis! Doubt me not, my loved one" (Aline)

- 21. "Oh, my voice is sad and low" (Dr Daly)

- 22. "Oh, joyous boon! oh, mad delight" (Aline, Alexis, Dr Daly, and Chorus)

- 23. "Prepare for sad surprises" (Alexis)

- 24. Act II Finale: "Or he or I must die" (leading to a reprise of "Now to the banquet we press") (Ensemble)

Productions

The Sorcerer opened on 17 November 1877 at the Opera Comique, preceded by Dora's Dream, a curtain-raiser composed by Sullivan's assistant Alfred Cellier, with words by Arthur Cecil, a friend of both Gilbert's and Sullivan's.[28] Busy with last-minute cuts and changes the day before the show opened, Sullivan had no time to write an overture and used the "Graceful Dance" music from his incidental music to Henry VIII, together with a few measures of music from "Oh Marvellous Illusion", as an overture. For the 1884 revival, an overture was composed by Sullivan's assistant, Hamilton Clarke.[28] Gilbert's meticulous rehearsal of the cast was noticed and commented on favourably by the critics, and the opening-night audience was enthusiastic.[30] The Sorcerer ran for 178 performances, making a profit.[31] A touring company also began playing the opera in March 1878.[32] D'Oyly Carte continued touring the piece in the early 1880s.[33] Unauthorised productions played on Broadway and elsewhere in the U.S. beginning by 1879.[34][35] The original London sets were by W. Beverly, and costumes were by C. Wilhelm.[36]

The Sorcerer was revived in 1884, the first of Gilbert and Sullivan's full-length operas to be revived. Except for The Mikado, it had a second London revival sooner than any of their other works, in 1898. The D'Oyly Carte Opera Company generally played Trial by Jury as a companion piece with the opera. In America, The Sorcerer was played as early as 1879 by the Adah Richmond Comedy Opera Troupe at Boston's Gaiety Theatre.[37] In Australia, its first authorised production opened on 22 May 1886 at the Theatre Royal, Melbourne, produced by J. C. Williamson, starring Frank Thornton, Nellie Stewart and Alice Barnett, conducted by Alfred Cellier,[38] although unauthorised productions had appeared by 1879.[39]

In the early years of the 20th century, however, The Sorcerer gradually fell out of favour in Britain. As discussed below, it draws on an older theatrical tradition and satirises social and operatic conventions that are less accessible to modern audiences than the ones explored in the more famous G&S works starting with H.M.S. Pinafore.[40] The D'Oyly Carte Opera Company, which had exclusive rights to the opera in Britain, dropped The Sorcerer in 1901, and its principal repertory company did not play the piece again until 1916, after which it made its first professional London appearance in over twenty years in 1919. The company played the opera only intermittently during the 1920s and early 1930s. In 1938 and 1939, it was performed only in the company's London seasons, and only for a handful of performances. During the winter of 1941–42, the scenery and costumes for The Sorcerer and three other operas were destroyed in enemy action.[41] The opera was not revived professionally in the UK until 1971.[42] Amateur British companies followed suit, as many dropped it from their repertory of the Gilbert and Sullivan operas during these three decades, although American companies often continued their regular rotation of the eleven operas from Trial through The Gondoliers.[43]

Outside the U.K., however, the opera continued to be played regularly in Australasia by the J. C. Williamson Opera Company,[44] and it was revived on Broadway in 1915 with DeWolf Hopper in the title role.[45] It was played by the American Savoyards in the United States from the 1950s and by other professional companies in the U.S. thereafter.[46][47] After 1970, The Sorcerer was included in the D'Oyly Carte repertory through the 1975 centenary season, then dropped for several years, then restored for the company's last few seasons before it closed in 1982. Amateur companies that had dropped the opera restored it to their rotations after the 1970 revival, and it still receives regular productions, both professional and amateur.[48]

The following table summarises the main London productions of The Sorcerer during Gilbert and Sullivan's lifetimes:

| Theatre | Opening Date | Closing Date | Perfs. | Details |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Opera Comique[49] | 17 November 1877 | 24 May 1878 | 178 | Trial by Jury was added to the bill from 23 March 1878 |

| Savoy Theatre[50] | 11 October 1884 | 12 March 1885 | 150 | Revised version; played with Trial by Jury |

| Savoy Theatre[51] | 22 September 1898 | 31 December 1898 | 102 | Played with Trial by Jury |

Reception

1877 reaction

The early reviews were generally favourable.[30] According to The Times, The Sorcerer "achieved a genuine success, and, moreover, a success in every respect deserved".[52] The Era praised both libretto and music: "the libretto, both in the prose and poetical portions, displays remarkable facility in writing fanciful and witty dialogue; and the lively flow of Mr. Sullivan's music, always tuneful, bright, and sparkling, and frequently reaching a very high standard of excellence, could hardly fail to please."[53] Lloyd's Weekly Newspaper called it "a very amusing work",[54] and Reynolds's Newspaper proclaimed it "one of the best entertainments of the kind that has yet been placed on the stage".[55] As with their previous opera, Trial by Jury, the integration of Gilbert's words and Sullivan's music was emphasised. The Times commented that "the music is spontaneous, appearing invariably to spring out of the dramatic situations, as though it was their natural concomitant";[52] The Musical Times mused that "it seems as if every composition had grown up in the mind of the author as he wrote the words"; and[56] The Pall Mall Gazette called the union between composer and librettist "well-assorted", arguing that "the opera contains several very happily designed pieces, in which one cannot tell (and need not know) whether the merit of the original underlying idea belongs to the composer of the poem or to the author of the score".[57]

A dissenting voice was Figaro, which claimed that there was nothing in The Sorcerer that could not have been written by "any theatrical conductor engaged at a few pounds a week".[58] It also criticised Sullivan for wasting his talent on comic opera; such criticism would follow him through the rest of his career.[59] Monthly Musical Record objected to the comic depiction of a clergyman, commenting that "the earnest, hard-working, and serious Clergy should not be made the subject of sneering caricature upon the stage",[60] and Lewis Carroll wrote in his 1888 essay:

Mr. Gilbert – to whom we owe a deep debt of gratitude for the pure and healthy fun he has given us in such comedies as "Patience" – seems to have a craze for making bishops and clergymen contemptible. Yet are they behind other professions in such things as earnestness, and hard work, and devotion of life to the call of duty? That clever song "The pale young curate", with its charming music, is to me simply painful. I seem to see him as he goes home at night, pale and worn with the day's work, perhaps sick with the pestilent atmosphere of a noisome garret where, at the risk of his life, he has been comforting a dying man – and is your sense of humour, my reader, so keen that you can laugh at that man?[61]

.jpg)

Four numbers were encored during the opening night: Aline's aria "Oh, happy young heart", "My name is John Wellington Wells", the Act II quintet "I rejoice that it's decided" and Sir Marmaduke's and Lady Sangazure's duet "Welcome joy, adieu to sadness".[62] The Observer called this duet "a masterpiece of construction. ... The Baronet sings to the accompaniment of a gavotte, and suddenly bursts forth into a rapid semi-quaver passage, expressive of his admiration of the lady. She follows his example, and while one sings a slow movement the other sings the presto movement alternatively".[63] The Era called the quintet "the gem of the opera", because it is "written with delightful fluency and grace, is admirably harmonised, and the melody is as fresh as May dew."[64] Punch argued that "the quintette and the old-fashioned duet with minuet step are the two best numbers" in the opera.[65]

Revivals and later assessments

Both revivals during the composer's lifetime were successful. The Times called the 1884 revival "distinctly a step in the right direction"[66] and in 1898 the paper claimed that "The Sorcerer is very far from having exhausted its popularity".[67] A review of the 1886 Australian production ranked the opera in "a middle place in Gilbert and Sullivan compositions. Abounding in tuneful numbers, one or two of which rank with anything that has come from Sir Arthur Sullivan's pen, the orchestration is thin compared with that of his later operas and its melodies have never taken the same popular hold as those of Pinafore, a work of about equal calibre from a musical point of view. ... The libretto is sparkling and pungent, and the idea of presenting a British bagman in the guise of a controller of demons and vendor of family curses is as happy a conception as any which has taken form on this modern stage".[68]

Later assessments of the opera have often mentioned both the opera's strong and weak points. Audrey Williamson wrote in a 1982 book that the virtues of The Sorcerer, "in spite of its defects ... justify its place in the repertoire."[69] In 1996, Ian Bradley commented in the introduction to his annotated edition of the Gilbert and Sullivan libretti, "It will certainly be a great pity if it gradually fades away. The Sorcerer contains two of W. S. Gilbert's best-drawn characters, the soulful Dr Daly ... and the flashy but ultimately tragic figure of John Wellington Wells. Sir Arthur Sullivan's music is delightful and guaranteed to weave a magic spell over all those who hear it, if not actually to make them fall instantly in love with their next-door neighbours."[70] The New York Times commented in 2012 that the plot "has not aged especially well. Its references to rank are dated beyond empathy’s reach; filled with sly allusions, its assumptions about a general audience's musical knowledge are unrealistic. Without those cues what remains is neither as exotic nor as amusing as Pinafore, Pirates or The Mikado. Still, The Sorcerer packs ample charms, including a felicitous score, a Verdian drinking song turned to teetotal ends, and at least one chorus that has reached the periphery of pop culture. ... the work can entrance a modern audience".[71] However, Isaac Goldberg, one of the first Gilbert scholars, in 1913 called it "the weakest of Gilbert's productions".[72]

Analysis

Text and music

The satire in the opera is focused on old-fashioned customs, pastoral opera conventions, the "popularity of curates, the pose of aristocratic benevolence, and the inebriety of the working man" rather than the broad political satire that would feature in many of the later Savoy opera librettos.[73] For example, "Sir Marmaduke, my dear young friend Alexis", a recitative among Alexis, Sir Marmaduke and Dr Daly, is a skit on the excessive politeness associated with early nineteenth-century aristocracy,[74] and the incantation scene is a parody of the similar scene in Weber's Der Freischütz.[75] Dr Daly accompanies his Act II song on a flageolet.[76] Gilbert satirises the Victorian temperance movement by introducing a non-alcoholic brindisi with jorums of tea; this is also a dig at Italian operas, many of which contained a brindisi scene.[77] Another burlesque of Italian opera is "Prepare for sad surprises", which is similar to Alfredo's denunciation of Violetta in Verdi's La traviata.[58] Gilbert's satire of these subjects, like most of his satire in the operas, was blunted with gentle humour. As Gilbert scholar Andrew Crowther explains, Gilbert characteristically combines his criticisms with comic entertainment, which renders them more palatable, while at the same time underlining their truth: "By laughing at a joke you show that you accept its premise."[78] Theatrical critic Allardyce Nicoll compared J. W. Wells' speech about blessings being less popular than curses to Mr. Hen's satiric auction speech in The Historical Register for the Year 1736 by Henry Fielding.[79]

The characters in The Sorcerer have family names that characterise them. Pointdextre is French for dexter point, a heraldic term; Sangazure is French for blue blood. Partlet means hen.[80] The two characters sing a duet, "Welcome, joy, adieu to sadness!" that contrasts and combines a "Mozart-like minuet" and rapid-fire patter. Other musical numbers that characterise the opera are the quintet in Act II, "I rejoice that it's decided", which is "one of the prettiest things Sullivan ever wrote in the Mendelssohnian manner ... while in the duet that follows between Mr. Wells and Lady Sangazure there is a divertingly sepulchral andante and a no less comic tarentello-like allegro".[73] The Sorcerer has certain technical difficulties in its production. It is the only Savoy opera to require trap, which many modern theatres do not have,[81] and requires a pyrotechnical effect for a flash in the incantation scene.[82]

_cropped.jpg)

In addition to Gilbert's story, An Elixir of Love, critics have traced several ideas in the opera to earlier sources. The concept of a love philtre was widespread in nineteenth century opera,[83] and a philtre that causes people to fall in love with first person who they see is found in Shakespeare's A Midsummer Night's Dream.[84] The idea of depicting the sorcerer as a respectable tradesman is comparable to the respectable friar in E. L. Blanchard's 1863 burlesque, Harlequin and Friar Bacon, who is described as a "Licensed Dealer in Black Art".[85] A drinking-chorus with tea instead of alcoholic drink appeared in Gilbert's The Merry Zingara (1868), a burlesque of The Bohemian Girl.[84] In "My name Is John Wellington Wells", Gilbert reused rhymes from one of his Bab Ballads, The Student.[86]

Some commentators have argued that the opera's relatively low popularity[87] is due to satire that relies on Victorian era class distinctions; it may not be clear to the modern audience why a baronet cannot marry a pew-opener, while in the Victorian era it was self-evident.[40] Also, the humour in the piece relies in many instances on parodies of operatic conventions that may be unfamiliar to some audiences. In 1913, E. J. Dent wrote in reference to The Sorcerer: "It seems as if a course of Mozart in English might be the best preliminary step towards educating our on-coming public to a really intelligent appreciation of Sullivan".[88] Gilbert scholar Andrew Crowther argues that while both The Sorcerer and H.M.S. Pinafore satirise the idea of love levelling all ranks, the earlier opera attacks it more aggressively, offending audiences with which that idea was popular.[89] Gilbert acknowledged that his position as a dramatist was similar to one of "a refreshment contractor who has engaged to supply a meal of one dish at which all classes of the community are to sit down", since he needed to suit needs of both "butcher-boy in the gallery" and "epicure in the stalls"; Crowther argues that he did not succeed as well at this in The Sorcerer as in some of the later works.[90]

Pattern for later Savoy operas

The opera establishes several important patterns for future Gilbert and Sullivan works. First, several recurring character types that would appear in their later operas are included: a comic baritone character with an autobiographical patter song (J. W. Wells)[91] and a tenor and soprano as young lovers (Alexis and Aline). Those types can be traced back to Italian comic opera and commedia dell'arte.[92] Character roles for a bass-baritone (Sir Marmaduke) and contralto (Lady Sangazure) are also repeated in the later Savoy operas. The vicar's song, "Time was when love and I were well acquainted" is one of the first in a string of meditative "Horatian" lyrics in the Savoy operas, "mingling happiness and sadness, an acceptance and a smiling resignation".[93] These would allow characters in each of the Savoy operas an introspective scene where they stop and consider life, in contrast to the foolishness of the surrounding scenes.[94]

One notable innovation that is characteristic of the Gilbert and Sullivan operas, and confirmed by its extensive use in The Sorcerer, is the employment of the chorus as an essential part of the action. In most earlier operas, burlesques and comedies, the chorus had very little impact on the plot and served mainly as "noise or ornament".[95] In the Savoy operas, however, the chorus is essential, taking part in the action and often acting as an important character in its own right.[95] The Sorcerer also confirms a pattern that had been introduced in the earlier collaborations and would be repeated in the other Savoy operas, except for The Yeomen of the Guard, to begin with a chorus number and end with a relatively short finale consisting of solos and chorus music.[96] Sullivan later told his biographer, "Until Gilbert took the matter in hand choruses were dummy concerns, and were practically nothing more than a part of the stage setting."[97] Another Gilbert innovation, following the example of his mentor, T. W. Robertson, was that the costumes and sets were made as realistic as possible.[98] This attention to detail would be repeated in all of the operas.[99] This was far from standard procedure in Victorian drama, where naturalism was still a relatively new concept, and where most authors had very little influence on how their plays and libretti were staged.[100]

The Sorcerer also contained several musical techniques that would become typical in the operas. One of the most important ones is the comic baritone's lightly orchestrated, rapid-fire patter song, which would become one of the most distinguishing and popular features of Gilbert and Sullivan operas. Following Italian opera precedents, such as "Largo al factotum" from The Barber of Seville, these numbers juxtapose virtuosity in their speed of delivery (requiring clarity of elocution) with their often comic or satiric lyrics. In "My name is John Wellington Wells", the title character of The Sorcerer introduces himself as a tradesman of an ironic kind: "a dealer in magic and spells".[101] Another typical Sullivanian musical technique is the contrapuntal combination of slow and rapid tunes in one song and a tenor aria set in 6/8 time. Sullivan did this so frequently in the Savoy operas that comedian Anna Russell, in her comedy routine "How to Write Your Own Gilbert and Sullivan Opera",[102] exclaimed, "the tenor ... according to tradition, must sing an aria in 6/8 time".[103] Another repeated musical technique was the emphasis of a single syllable to distinguish otherwise identical lines. For example, in the vicar's Act I song, the same melody is sung in each of the two stanzas using the following text:

- Stanza 1: A saintly youth, by worldly thought untainted

- Stanza 2: Did I look pale? Then half a parish trembled

In the second, the syllable trem has an optional high note to give it a unique character.[104]

Several ideas from The Sorcerer were reused in later Savoy operas. Many images from "Have faith in me", Aline's cut ballad, are present in "None shall part us" in Iolanthe.[105] Another example is satire on the aristocracy: while in The Sorcerer Lady Sangazure is in direct descent from Helen of Troy, in The Mikado Gilbert developed this idea, and Pooh-Bah can trace his ancestry "back to a protoplasmal primordial atomic globule".[106]

Revisions and cut material

Initial cuts and changes

Gilbert initially wrote a duet for Aline and Lady Sangazure, "Oh, why thou art sad, my mother?", followed by a ballad for Sangazure, "In days gone by, these eyes were bright". These numbers were cut before opening night, although the ballad was included in the first published version of the libretto.[107] Alexis's Act II ballad ("Thou hast the power") was revised, with the refrain changed from common time to waltz time. Although performed on opening night, it was not included in the original vocal score. Available evidence suggests that the ballad was dropped from the opera, but later reinstated during the original run.[108] It was a substitute for Aline's ballad, "Have faith in me", which was present in the license copy but cut before the first night and absent from the published version of libretto.[105] Some of the text was reused in "None shall part us" in Iolanthe.[109] The second verse of Constance's Act I aria, "When he is here", was also cut during the original production.[110]

The Act I finale was shortened during the original production to omit a reprise of the Brindisi after the "Oh marvellous illusion" chorus, and Constance's Act II song was transposed downwards.[111] Originally, in the Act II finale, there was a second incantation in which J. W. Wells summoned Ahrimanes (to be played by Mrs Paul),[112] who told him that either he or Alexis must yield his life to quell the spell. This scene was cut, although its opening recitative in rewritten form was present in the first production.[113]

1884 revival

The opera was extensively revised for the 1884 revival. An overture was arranged by Sullivan's assistant, Hamilton Clarke, to replace Sullivan's "graceful dance" from his incidental music to Henry VIII.[28] The length of time between the acts was altered from a half-hour to twelve hours, and the Act II opening was rewritten.[114] Act II originally started off with a patter chorus, "Happy are we in our loving frivolity", a pageant of mismatched couples. The revision changed the setting to nighttime, with a mysterioso trio for Alexis, Aline and John Wellington Wells to sing among the sleeping villagers.[115] The villagers then awaken with a rustic chorus in West Country accent and pair up in the mismatched couples.[116]

These revisions were not, however, done very carefully. The Act I Finale still says "Their hearts will melt in half-an-hour / Then will be felt the potion's power."[117] Similarly, Aline drinks the potion in Act II, and falls insensible, but apparently awakes immediately to fall in love with Dr Daly, instead of falling asleep for twelve hours as the revisions would require.[118]

Historical casting

The following tables show the casts[119] of the principal original productions and D'Oyly Carte Opera Company touring repertory at various times through to the company's 1982 closure:

| Role | Opera Comique, 1877[49] | Savoy Theatre, 1884[50] | Savoy Theatre, 1898[51] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sir Marmaduke | Richard Temple | Richard Temple | Jones Hewson |

| Alexis | George Bentham | Durward Lely | Robert Evett |

| Dr Daly | Rutland Barrington | Rutland Barrington | Henry Lytton |

| Notary | Fred Clifton | William Lugg | Leonard Russell |

| J. W. Wells | George Grossmith | George Grossmith | Walter Passmore |

| Lady Sangazure | Mrs Howard Paul | Rosina Brandram | Rosina Brandram |

| Aline | Alice May | Leonora Braham | Ruth Vincent |

| Mrs. Partlet | Harriett Everard | Ada Doree | Ethel McAlpine |

| Constance | Giulia Warwick | Jessie Bond | Emmie Owen |

| Oldest Inhabitant | Frank Thornton1 | — | — |

| Role | D'Oyly Carte Tour 1919[120] | D'Oyly Carte Tour 1930[121] | D'Oyly Carte Tour 1939[122] | D'Oyly Carte Tour 1971[123] | D'Oyly Carte Tour 1982[124] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sir Marmaduke | Frederick Hobbs | Darrell Fancourt | Darrell Fancourt | John Ayldon | Clive Harre |

| Alexis | Derek Oldham | Charles Goulding | John Dean | Ralph Mason | Meston Reid |

| Dr Daly | Leo Sheffield | Leslie Rands | Leslie Rands | Kenneth Sandford | Kenneth Sandford |

| Notary | George Sinclair | Joseph Griffin | Richard Walker | John Broad | Bruce Graham |

| J. W. Wells | Henry Lytton | Henry Lytton | Martyn Green | John Reed | James Conroy-Ward |

| Lady Sangazure | Bertha Lewis | Bertha Lewis | Evelyn Gardiner | Lyndsie Holland | Patricia Leonard |

| Aline | Elsie Griffin | Winifred Lawson | Margery Abbott | Julia Goss | Pamela Field |

| Mrs. Partlet | Anna Bethell | Anna Bethell | Anna Bethell | Peggy Ann Jones | Beti Lloyd-Jones |

| Constance | Catherine Ferguson | Marjorie Eyre | Marjorie Eyre | Linda Anne Hutchison | Lorraine Daniels |

1This role is not credited in revivals, which used a revised libretto.

Recordings

The Sorcerer has not been recorded as often as most of the other Gilbert and Sullivan operas, and the recordings have not been generally well received. The 1966 D'Oyly Carte Opera Company recording is considered the best of their efforts to record this opera.

The 1982 Brent Walker video is considered to be one of the best of that series and is recommended.[125] More recent professional productions have been recorded on video by the International Gilbert and Sullivan Festival.[126]

- Selected recordings

- 1933 D'Oyly Carte, selections only – Conductor: Isidore Godfrey[127]

- 1953 D'Oyly Carte – New Symphony Orchestra of London; Conductor: Isidore Godfrey[128]

- 1966 D'Oyly Carte – Royal Philharmonic Orchestra; Conductor: Isidore Godfrey[129]

- 1982 Brent Walker Productions – Ambrosian Opera Chorus, London Symphony Orchestra; Conductor: Alexander Faris; Stage Director: Stephen Pimlott (video)[130]

Cultural impact

The Sorcerer has made its way into popular culture. Isaac Asimov wrote a short story, "The Up-To-Date Sorcerer", an homage to the opera consisting largely of a series of puns on phrases from it.[131] Charlotte MacLeod's 1985 mystery novel, The Plain Old Man concerns an amateur production of the opera.[132] A series of seven novels by Tom Holt concern young sorcerers who join the firm of "J. W. Wells & Co": The Portable Door (2003), In Your Dreams (2004), Earth, Air, Fire, and Custard (2005), You Don't Have to Be Evil to Work Here, But It Helps (2006), The Better Mousetrap (2008), May Contain Traces of Magic (2009) and Life, Liberty and the Pursuit of Sausages (2011).[133] In Meet Mr Mulliner by P. G. Wodehouse, the title hero sings a fragment from Dr Daly's ballad and characterises his nephew as "the sort of young curate who seems to have been so common in the 'eighties, or whenever it was that Gilbert wrote The Sorcerer."[134] It has also been referenced in popular TV series, such as in the Family Guy episode "Patriot Games", where characters sing the song "If you'll marry me" from Act II.[135]

Notes

- ↑ Ainger, p. 94

- ↑ Ainger, p. 108

- ↑ Ainger, p. 109

- ↑ Stedman, pp. 128–29

- ↑ Stedman, pp. 129–30

- ↑ The Times, 29 March 1875, quoted and discussed in Ainger, p. 109

- ↑ Ainger, pp. 111; 117–18

- ↑ Gänzl, pp. 89–90

- 1 2 Stedman, p. 132

- ↑ Ainger, p. 112

- ↑ Ainger, pp. 113–14

- ↑ Ainger, p. 110

- ↑ Ainger, p. 130

- ↑ Ainger, p. 131

- ↑ Ainger, p. 132

- ↑ In the short story, the elixir is used to help the villagers overcome the difficulty that they have in expressing their true feelings and achieving domestic happiness in the face the convoluted Victorian rules of courtship.

- ↑ The device of a magic potion can also be found in some of his earlier works: a Bab Ballad 'The Cunning Woman' and his first early Victorian burlesque, Dulcamara, as well as later works, such as Foggerty's Fairy and The Mountebanks. See Bradley (1996), p. 43

- ↑ Jacobs, p. 111; Ainger, pp. 133–34

- ↑ Mrs Paul left her husband (Howard Paul, 1830–1905) around 1877, as he was having an affair with the actress-dancer Letty Lind, with whom he sired two illegitimate children. However, she continued performing under this name, often humorously impersonating the famous tenor Sims Reeves. See Barringon, p. 21

- ↑ Ayre, p. 48

- ↑ Stone, David. "Rutland Barrington" at the Who Was Who in the D'Oyly Carte website (G&S Archive), accessed 9 March 2008

- ↑ Ainger, p. 134

- ↑ Grossmith profile at the Memories of the D'Oyly Carte website, accessed 9 March 2008

- 1 2 Ainger, p. 138

- 1 2 Ainger, p. 136

- ↑ Ayre, p. 137

- ↑ Ainger, pp. 134–35

- 1 2 3 4 Ainger, p. 140

- ↑ An examination of the 1877 and 1884 scores Archived 10 June 2010 at the Wayback Machine. shows the lowered keys. David Mackie, the associate musical director of the D'Oyly Carte Opera Company from 1976 to 1982, wrote and presented 14 interval talks on BBC Radio 2, for the network's 1989 series of the complete Gilbert & Sullivan operas. In his talk on The Sorcerer, broadcast on 1 October 1989, he stated that the keys were lowered to accommodate Bond.

- 1 2 Ainger, p. 141

- ↑ Ainger, pp. 147–48

- ↑ Ainger, p. 152. In the touring company, Rosina Brandram played Lady Sangazure, and J. H. Ryley was Wells.

- ↑ Moss, Simon. "Gilbert & Sullivan". Theatre programmes of The Sorcerer with details on exhibition at the C20th.com archive, accessed 26 August 2010

- ↑ The Sorcerer at the IBDB Database, accessed 26 August 2010

- ↑ Kanthor, Harold. "Gilbert and Sullivan: From London to America". An exhibition of historical items, University of Rochester, accessed 26 August 2010

- ↑ Rollins and Witts, Appendix, p. VII

- ↑ Programme of 13 March 1879

- ↑ See Moratti, Mel. "Down Under in the 19th Century" and Reviews of The Sorcerer. Melbourne Age, 24 May 1886 and Argus, 24 May 1886.

- ↑ See these 1879 Reviews of early productions of The Sorcerer in Australia (The Melbourne Argus, 29July 29 1879) and in New Zealand (New Zealand Herald, 26 May 1879)

- 1 2 Crowther, p. 98

- ↑ Rollins and Witts, p. 165

- ↑ Bradley (2005), p. 40. The new production was directed by Michael Heyland and had new costume and set designs by Osbert Lancaster. See: "The Sorcerer to be revived", The Times , 5 March 1971, p. 10

- ↑ See, e.g., The Savoy Company and The Blue Hill Troupe, Ltd. theatre programmes throughout the 20th century and to present.

- ↑ See, e.g., this photo of Viola Wilson Tait as Aline in J. C. Williamson's 1941 production, accessed 16 August 2010

- ↑ "The Sorcerer" 1915 revival at the IBDB database, accessed 26 August 2010

- ↑ "The Sorcerer: American Savoyards". Lortel Archives information re: 1954 production, accessed 19 October 2010

- ↑ Ericson, Raymond. "Music: Gilbert and Sullivan Treat". The New York Times, 15 October 1977, p. 13, accessed 19 October 2010

- ↑ For example, Opera della Luna toured the piece from February to April 2010. See the company's Diary of Performances, accessed 22 August 2010. The New York Gilbert and Sullivan Players revives the opera every few years. See, e.g., New York Magazine review of 1987 production; "Classical Music and Dance Guide: Trial by Jury and The Sorcerer". The New York Times, 12 January 2001, accessed 16 August 2010; and Smith, Steve. "Gilbert and Sullivan Made Jokes About Costco and Smartphones? Who Knew?", The New York Times, 3 December 2012

- 1 2 Rollins and Witts, p. 5

- 1 2 Rollins and Witts, p. 9

- 1 2 Rollins and Witts, p. 17

- 1 2 "The Opera Comique". The Times, 19 November 1877, accessed 21 July 2010

- ↑ "The Opera Comique". The Era, 25 November 1877, accessed 21 July 2010

- ↑ "Opera Comique". Lloyd's Weekly Newspaper, 25 November 1877, accessed 21 July 2010

- ↑ "The Sorcerer at the Opera Comique". Reynolds's Newspaper, 25 November 1877, accessed 21 July 2010

- ↑ The Musical Times, 17 November 1877, reprinted in The Musical Times, 1 October 1898, p. 39, accessed 21 July 2010

- ↑ "Opera Comique". The Pall Mall Gazette, 19 November 1877, accessed 21 July 2010

- 1 2 Stedman, p. 154

- ↑ Jacobs, p. 116

- ↑ Review of The Sorcerer. Monthly Musical Record, 1 January 1878, p. 7, accessed 28 August 2010

- ↑ Carroll, Lewis (January–June 1888). "The Stage and the Spirit of Reverence". In Clement Scott. The Theatre. XI. Strand Publishing Company. p. 291. Retrieved 28 August 2010.

- ↑ Bradley (1996), p. 57

- ↑ Bradley (1996), p. 60

- ↑ Bradley (1996), p. 96

- ↑ "The Opera Comique". Punch, 16 March 1878, p. 74, accessed 21 July 2010

- ↑ "Savoy Theatre". The Times, 13 October 1884, accessed 23 July 2010

- ↑ "Savoy Theatre". The Times, 23 September 1898, accessed 23 July 2010

- ↑ Review of the first Australian production of 1884 version. Melbourne Age, 24 May 1886, accessed 27 August 2010

- ↑ Williamson, p. 53

- ↑ Bradley (1996), pp. 44–45

- ↑ Smith, Steve. "Gilbert and Sullivan Made Jokes About Costco and Smartphones? Who Knew?", The New York Times, 3 December 2012

- ↑ Goldberg, Isaac (1913). Sir William S. Gilbert: A Study in Modern Satire. Boston: Stradford Publishing Co. p. 91.

- 1 2 Walbrook, chapter IV

- ↑ Bradley (1996), p. 52

- ↑ Bradley (1996), p. 74

- ↑ Bradley, p. 104

- ↑ Bradley (1996), p. 80

- ↑ Crowther, pp. 78–79

- ↑ Nicoll, pp. 142–43

- ↑ Bradley (1996), p. 46

- ↑ Bradley (1996), p. 110

- ↑ Bradley (1996), p. 78

- ↑ Williamson, p. 41

- 1 2 Jacobs, p. 114

- ↑ Stedman, p. 153

- ↑ Ellis, p. 317

- ↑ Bradley (1996), p. 44

- ↑ Hughes, p. 150

- ↑ Crowther, pp. 97–105, passim

- ↑ Crowther, p. 99

- ↑ Fitzgerald, pp. 25–26

- ↑ Jacobs, p. 115

- ↑ Stedman, p. 244

- ↑ Stedman, pp. 129–30, 244; Crowther, pp. 133–35

- 1 2 Dark and Grey, pp. 67–68

- ↑ Bradley (1996), p. 758

- ↑ Lawrence, pp. 85–86

- ↑ Stedman, pp. 129 and 157–58

- ↑ Crowther, p. 90

- ↑ Crowther, pp. 87–89

- ↑ Benford, p. 30

- ↑ Recording and re-issue history available at: Shepherd, Marc (2002), "How to Write Your Own Gilbert and Sullivan Opera (1953)", A Gilbert and Sullivan Discography, Retrieved on 12 June 2008.

- ↑ Anna Russell Sings! Again? 1953 Columbia Masterworks Mono LP ML4594/ML4733

- ↑ Jacobs, pp. 114–15

- 1 2 Bradley (1996), p. 92

- ↑ Williamson, pp. 45–46

- ↑ Bradley (1996), p. 58

- ↑ Hulme, p. 3

- ↑ D'Orsay, Stan. "Gilbert & Sullivan: Of Ballads, Songs and Snatches; Lost or seldom recorded". The Gilbert and Sullivan Discography, October 2003, accessed 9 August 2010

- ↑ Shepherd (2015), p. 424

- ↑ Shepherd (2015), p. 415

- ↑ Barrington, p. 24

- ↑ Bradley (1996), p. 100

- ↑ Bradley (1996), pp. 66 and 84

- ↑ Bradley (1996), p. 84

- ↑ Bradley (1996), p. 86

- ↑ Bradley (1996), p. 81

- ↑ Some productions introduce a sunrise here to indicate the passage of time.

- ↑ Stone, David. Who Was Who in the D'Oyly Carte Opera Company, Boise State University, accessed 17 August 2015. This site contains biographies of the persons listed in these tables.

- ↑ Rollins and Witts, p. 136

- ↑ Rollins and Witts, p. 154

- ↑ Rollins and Witts, p. 164

- ↑ Rollins and Witts, 2nd Supplement, p. 17

- ↑ Rollins and Witts, 4th Supplement, p. 42

- ↑ Shepherd, Marc. "Recordings of The Sorcerer" at A Gilbert and Sullivan Discography, 8 July 2009, accessed 26 August 2010

- ↑ "Professional Shows from the Festival", Musical Collectibles catalogue website, accessed 15 October 2012

- ↑ Shepherd, Marc. The 1933 HMV Sorcerer [abridged] at A Gilbert and Sullivan Discography, 24 August 2008, accessed 26 August 2010

- ↑ Shepherd, Marc. The 1953 D'Oyly Carte Sorcerer at A Gilbert and Sullivan Discography, 11 July 2009, accessed 26 August 2010

- ↑ Shepherd, Marc. The 1966 D'Oyly Carte Sorcerer at A Gilbert and Sullivan Discography, 10 May 2003, accessed 26 August 2010

- ↑ Shepherd, Marc. The Brent Walker Sorcerer (1982) at A Gilbert and Sullivan Discography, 5 April 2009, accessed 26 August 2010

- ↑ Asimov, pp. 563–75

- ↑ MacLeod, Charlotte, The Plain Old Man, New York: Doubleday, 1985. See "The Sorcerer Plot", for an excerpt from the book's introduction reprinted at The Gilbert and Sullivan Archive, accessed 22 July 2020

- ↑ "J. W. Wells & Co. series", Goodreads.com, accessed 6 January 2014

- ↑ Wodehouse, Pelham Grenville (1927). Meet Mr. Mulliner. London: H. Jenkins.

- ↑ See Family Guy: Volume Four: Commentary for "Patriot Games", DVD Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation, 14 November 2006. In the episode, Peter goes to England to play for an American football team called the London Silly Nannies, who practice by prancing around a maypole singing "If you'll marry me".

References

- Ainger, Michael (2002). Gilbert and Sullivan – A Dual Biography. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-514769-3.

- Asimov, Isaac (1990). "The Up-to-Date Sorcerer". The complete stories. Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-385-41627-6.

- Ayre, Leslie (1972). The Gilbert and Sullivan Companion. London: W.H. Allen & Co Ltd. ISBN 978-0-396-06634-7.

- Barrington, Rutland (1908). Rutland Barrington: A Record of 35 Years' Experience on the English Stage. London: G. Richards. Preface by W. S. Gilbert, accessed 9 March 2008.

- Benford, Harry (1999). The Gilbert & Sullivan Lexicon, 3rd Revised Edition. Ann Arbor, Michigan: The Queensbury Press. ISBN 0-9667916-1-4.

- Bradley, Ian, ed. (1996). The Complete Annotated Gilbert and Sullivan. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-816503-X.

- Bradley, Ian (2005). Oh Joy! Oh Rapture! The Enduring Phenomenon of Gilbert and Sullivan. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-516700-7.

- Gänzl, Kurt (1986). The British Musical Theatre—Volume I, 1865–1914. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Crowther, Andrew (2000). Contradiction Contradicted – The Plays of W. S. Gilbert. Associated University Presses. ISBN 0-8386-3839-2.

- Dark, Sidney and Rowland Grey (1923). W. S. Gilbert: His Life and Letters. Ayer Publishing. ISBN 0-405-08430-7. Retrieved 2008-06-17.

- Ellis, James, ed. (1980). The Bab ballads. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-05801-1.

- Fitzgerald, Percy Hetherington (1899). The Savoy Opera and the Savoyards. Chatto & Windus. Retrieved 2008-06-22.

- Hughes, Gervase (1959). The Music of Sir Arthur Sullivan. London: Macmillan & Co Ltd.

- Hulme, David Russell (1984). "Sidelights on The Sorcerer.". The Sorcerer and Trial by Jury – A Booklet to Commemorate The Centenary of the First Revival. Saffron Walden, Essex, UK: The Sir Arthur Sullivan Society. pp. 1–4.

- Jacobs, Arthur (1986). Arthur Sullivan – A Victorian Musician (second ed.). Amadeus Press. ISBN 0-931340-51-9.

- Nicoll, Allardyce (1959). A history of English drama, 1660–1900. Volume 5: Late Nineteenth Century Drama (second ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Rollins, Cyril; R. John Witts (1962). The D'Oyly Carte Opera Company in Gilbert and Sullivan Operas: A Record of Productions, 1875–1961. London: Michael Joseph. Also, five supplements, privately printed.

- Shepherd, Marc; Michael Walters, eds. (2015). The Variorum Gilbert & Sullivan. 1. New York: Oakapple Press.

- Stedman, Jane W. (1996). W. S. Gilbert, A Classic Victorian & His Theatre. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-816174-3.

- Walbrook, H. M. (1922). Gilbert & Sullivan Opera, A History and a Comment. F. V. White & Co. Ltd. Retrieved 24 June 2009.

- Williamson, Audrey (1982). Gilbert and Sullivan Opera. London: Marion Boyars. ISBN 0-7145-2766-1.

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to The Sorcerer. |

- The Sorcerer at The Gilbert & Sullivan Archive

- The Sorcerer at The Gilbert & Sullivan Discography

- Cramer vocal score of The Sorcerer

- Modern notation vocal score prepared by Larry Byler

- Article on The Sorcerer by Ric Wilson

- The Sorcerer 21st Anniversary Souvenir, 1898

- Bab illustrations of lyrics from The Sorcerer

- Sorcerer song parody links, among others