The public scandal of the Dreyfus Affair

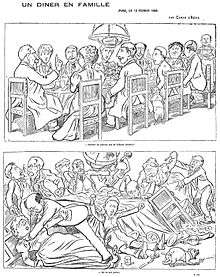

The debate over falsely accused Alfred Dreyfus grew into a public scandal of unprecedented scale, and caused most of the French nation to become divided between Dreyfusards and anti-Dreyfusards.

| Part of a series on the |

| Dreyfus affair |

|---|

| People |

Attitude of the press

Against this "odious campaign" was set in motion a whole band of newspapers connected with the Staff Office, and which received from it either subsidies or communications. Among the most violent are to be noted La Libre Parole (Drumont), L'Intransigeant (Henri Rochefort), L'Écho de Paris (Lepelletier), Le Jour (Vervoort), La Patrie (Millevoye), Le Petit Journal (Judet), L'Eclair (Alphonse Humbert). Two Jews, Arthur Meyer in Le Gaulois and G. Pollonnais in Le Soir, also took part in this concert. Boisdeffre's orderly officer, Pauffin de St. Morel, was even caught one day bearing the "staff gospel" to Henri Rochefort (16 November); nobody was deceived by the punishment for breach of discipline which he had to undergo for the sake of appearances.

An extraordinary piece of information (which was immediately contradicted) was printed by L'Intransigeant (12 December-14 December); it was attributed to the confidences of Pauffin, and it dealt with the "ultra-secret" dossier (the photographs of letters from and to Emperor William about Dreyfus).

The Revisionist press, reduced to a small number of organs which were accused of being in the service of a syndicate, did not remain inactive. It consisted of Le Siècle (Yves Guyot, Joseph Reinach), L'Aurore (Vaughan, Clémenceau, Pressensé), and Le Rappel, to which were joined later La Petite République (Jaurès) and Les Droits de l'Homme (Ajalbert). Le Figaro, losing most of its subscribers, changed its politics on 18 December, but became "Dreyfusard" once more after the discovery of Henry's forgery. L'Autorité (Cassagnac) and Le Soleil (Hervé de Kerohant) were the only newspapers among the reactionary press which were more or less in favor of revision. Some of the revisionists, falling into the trap laid for them, widened the scope of the debate and gave it the character of an insulting campaign against the chiefs of the army, which hurt the feelings of many sincere patriots and drove them over to the other side.

Public opinion was deeply moved by two publications: one, that of the indictment of Dreyfus (in Le Siècle, 6 January 1898), which was absolutely remarkable for its lack of proof; the other (Le Figaro, 28 November 1897), that of letters written twelve years before by Esterhazy to his mistress, Madame de Boulancy, in which he launched furious invectives against his "cowardly and ignorant" chiefs, against "the fine army of France," against the entire French nation. One of these letters especially, which soon became famous under the name of the "lettre du Hulan" (Uhlan), surpassed in its unpatriotic violence anything that can be imagined.

The "Lettre du Hulan"

"If some one came to me this evening," it ran, "and told me that I should be killed to-morrow as captain of Uhlans, while hewing down Frenchmen, I should be perfectly happy. . . . What a sad figure these people would make under a blood-red sun over the battle-field, Paris taken by storm and given up to the pillage of a hundred thousand drunken soldiers! That is the fête that I long for!"

Esterhazy hastened to deny having authored the letter, which was submitted to examination by experts. While silence was imposed on the officers of Esterhazy's regiment, suspicions were thrown on the defenders of Dreyfus. The director of the prison of Cherche-Midi, Forzinetti, who persisted in proclaiming his prisoner's innocence, was dismissed. The Staff Office struggled to bring Picquart into disrepute. Scheurer-Kestner insisted on having his evidence; they were forced to bring him back from Tunis. The day before his arrival his belongings were searched; an officer escorted him from Marscilles to Paris (25 November). General de Pellieux, who had been made to believe by a series of forgeries that Picquart had for some time been the moving spirit of the "syndicate," treated him more as an accused than as a witness.

The general entrusted with the investigation concluded that there was no evidence against Esterhazy. However, Esterhazy was instructed to write a letter asking as a favor to be brought up for trial, the rough copy of which was corrected by Pellieux himself. General Saussier, governor of Paris, instituted a regular inquiry (4 December). But the officer empowered to conduct it, Major Ravary, did so in the same spirit as Pellieux. Esterhazy's defence was to acknowledge his relations with Schwartzkoppen, giving them a purely social character. The "petit bleu" was, according to him, an absurd forgery, most likely the work of Picquart himself. He did not deny the striking resemblance between his writing and that of the bordereau, but explained it by alleging that Dreyfus must have imitated his handwriting to incriminate him. As for the documents enumerated in the bordereau, Esterhazy denied that he could possibly have known them, especially at the time to which they now had agreed to assign the bordereau (April, 1894). He had borrowed the "manuel de tir" from Lieutenant Bernheim of Le Mans, whom he had met at Rouen, but in the month of September; later on, he retracted and said, in agreement with Bernheim, that it was not the real manual, but a similar regulation already available in the bookstores.

This mass of deceptions, to which was added the romance of the "veiled lady" (supposed to be a mistress of Picquart) was taken seriously by Ravary. Three experts were found (Couard, Belhomme, Varinard) who swore that the bordereau was not in Esterhazy's hand, though apparently traced in part over his writing (26 December). These men were coached by the staff. Du Paty writes to Esterhazy: "The experts have been appointed. You will have their names to-morrow. They shall be spoken to; be quiet!" Thereupon Ravary wrote out, or signed, a long report which he concluded by saying that, while the private life of the major was not a model to be recommended, there was nothing to prove that he was guilty of treason. The bordereau was not in his writing; the "petit bleu" was not genuine. He stigmatized Picquart as the instigator of the whole campaign, and denounced his subterfuges and indiscretions to his superiors.

The Esterhazy court martial

Ravary concluded that the case should be dismissed at once (1 January 1898). However, Saussier ordered the affair to be thoroughly cleared up before a court martial presided over by General Luxer. The hearing took place at the Cherche-Midi on 10 January and 11 January 1898. From the commencement the Dreyfus family, who had appointed two lawyers (Labori and Demange), were refused the right of being represented in court. The reading of the indictment, the superficial examination of Esterhazy (who contradicted himself several times), the testimony of the civil witnesses (Mathieu Dreyfus, Scheurer-Kestner, etc.), were conducted in public; then a hearing behind closed doors was ordered, doubtless to stifle Colonel Picquart's evidence. The public knew nothing of Picquart's deposition, or of that of the other military witnesses, of Leblois, or of the experts, and nothing of the Revisionists' case in general. General de Pellieux, seated behind the judges, interfered more than once in the debates, and whispered to the president. Picquart was so harshly treated that one judge exclaimed: "I see that the real accused is Colonel Picquart!"

Finally, as everybody knew beforehand would be the case, Esterhazy was acquitted unanimously and acclaimed with frenzy by the "patriots" outside. Pellieux wrote to the "dear major" to stigmatize the "abominable campaign" of which he had been the victim, and to authorize him to prosecute those who dared to attribute the "Uhlan" letter to him. As to Picquart, he was, to begin with, punished with sixty days' imprisonment, being confined on Mont Valérien; it was understood that he would be arraigned before a council of inquiry (13 January).

Émile Zola's J'Accuse

Esterhazy's acquittal closed the door on revision for the time being; but the Revisionists did not consider themselves defeated. For two months their ranks had been increased by a large number of literary men, professors, and scholars who had been convinced by the evidence given; it was one of these "intellectuels," the novelist Émile Zola, who took up the gauntlet. Almost from the start he had enlisted among the advocates of revision. He had written in Le Figaro brilliant articles against the anti-Semites and in favor of Scheurer-Kestner, whom he termed "a soul of crystal." "Truth is afoot," he said; "nothing will stop her." On 13 January he published in L'Aurore, under the title J'Accuse, an open letter to the president of the republic, an eloquent philippic against the enemies "of truth and justice." Gathering together with the prophetic imagination of the novelist all the details of a story of which up to then the outlines had hardly been discerned, he threw into relief, not without a good deal of exaggeration, the "diabolical rôle" of Colonel Du Paty. He charged the generals with a "crime of high treason against humanity," Pellieux and Ravary with "villainous inquiry," the experts with "lying and fraudulent reports." The acquittal of Ferdinand Walsin Esterhazy was "a supreme blow ["soufflet"] to all truth, to all justice"; the court of justice which had pronounced it was "necessarily criminal"; and he finished the long recital of his accusations with these words:

"I accuse the first court martial of having violated the law in condemning the accused upon the evidence of a document which remained secret. And I accuse the second court martial of having screened this illegality by order, committing in its turn the judicial crime of wilfully [sic?] and knowingly acquitting a guilty person."

Zola's audacious action created a tremendous stir. It was, he said, a revolutionary deed destined to provoke proceedings which would hasten "an outburst of truth and justice," and in that respect he was not deceived. His tirade raised such an outcry in the press and in the Chamber of Deputies that the War Office was forced to enter upon proceedings. A complaint was lodged against the defamatory phrases with regard to the court martial which had acquitted Esterhazy. The case was tried before the jury of the Seine département, and lasted from 7 February to 23 February 1898.

First Zola trial

The "enemies of the army" were threatened, whilst the generals and even the most insignificant officers in uniform, not excepting Major Esterhazy, to whom Prince Henry of Orleans asked to be presented, were applauded. Scuffles took place between the anti-Revisionists and the handful of "Dreyfusards" who served as Zola's body-guard. Even in the audience-chamber, supposedly arranged with care, officers in civil dress caused a stir and gave vent to noisy manifestations. There was fighting in the lobbies. Cries of "Death to the Jews!" were uttered on all sides. Zola's lawyers, Fernand Labori and Albert Clemenceau, had summoned a large number of witnesses. Most of the military witnesses at first ignored the summons, but the court forced them to submit. However, the court decided not to allow any document or evidence which bore upon facts foreign to the accusation to be produced.

The president, Delegorgue, in applying this principle, observed a subtle distinction; he admitted all that could prove Esterhazy's guilt but not Dreyfus' innocence or the irregularity of his condemnation; his formula, "The question will not be admitted", soon became proverbial. It was difficult to draw a line between the two classes of facts; and the line was constantly overstepped, either under the pretext of establishing the "good faith" of the accused or to justify the incriminating phrase that the second court martial had covered by order the illegality committed by the first. Thus Demange was able to bring out, in a rapid sentence, the fact of the communication of the secret document, which fact he learned from his fellow advocate, Salles.

The most telling testimony was that of Colonel Picquart, who appeared for the first time in public, and gained numerous sympathizers by his calm, dignified, and reserved attitude. Without letting himself be either intimidated or flattered, he related clearly, sincerely, and succinctly, the story of his discovery. His adversaries, Gonse, Henry, Lauth and Gribelin, tried to weaken the force of his evidence and to assert that from the beginning he had been haunted by the idea of substituting Esterhazy for Dreyfus. There was a long dispute over his supposed plan of having the "petit bleu" stamped during the suspicious visits that Leblois had paid him at the ministry. Gribelin claimed to have seen them seated at a table with two secret dossiers in front of them, one concerning carrier-pigeons, the other concerning the Dreyfus affair. Henry (appointed lieutenant-colonel for the occasion) declared that he had seen, in the presence of Leblois, the document "Cette canaille de D . . ." taken from its envelope. Picquart denied this statement, which the dates contradicted; Henry thereupon replied: "Colonel Picquart has told a lie." Picquart kept his temper, but at the end of the trial sent his seconds to Henry, and fought a duel with him, in which Henry was slightly wounded. As to Esterhazy, who also tried to pick a quarrel with him, Picquart refused to grant him the honor of a meeting. "That man," said he, "belongs to the justice of his country." In this trial the important part played by Henry began to appear; till then he had purposely kept in the background, and concealed a deep cunning beneath the blunt appearance of a peasant-soldier. One day (13 February), as if to warn his chiefs that he had the upper hand of them, he revealed the formation of the secret dossier; he also spoke, but vaguely, of a supposed ultra-secret dossier, two letters which (he pretended) had been shown him by Colonel Sandherr. These were apparently two of the forged letters attributed to the German emperor, which were whispered about sub rosa in order to convince the skeptical.

Among the civil witnesses, the experts in handwriting occupied the longest time before the court. Besides the professional experts, savants such as Paul Meyer, Arthur Giry, Louis Havet, and Auguste Molinier affirmed and proved that the writing and the style of the bordereau were those of Esterhazy. Their adversaries refused to admit this evidence on the ground of the supposed difference between the original and the published facsimiles, of which many, according to Pellieux, resembled forgeries. The lawyers then asked that the original bordereau might be produced, but the court refused to give the order.

The "Thunderbolt" quoted

General de Pellieux had established himself counsel for the Staff Office. An elegant officer, gifted with an easy and biting eloquence, he addressed the court at almost every hearing, sometimes congratulating himself with having contributed to Esterhazy's acquittal, sometimes warning the jurymen that if they overthrew the confidence of the country in the chiefs of the army, their sons would be brought "to butchery." Like Henry, but with less mental reservation, he ended one day by divulging a secret. On 17 February he had a prolonged discussion with Picquart as to whether Esterhazy could possibly have been acquainted with the documents of the bordereau, the real date of which was now acknowledged (Aug. or Sept. and not April, 1894). Suddenly, as if unnerved, he declared that, setting the bordereau aside, there was a proof, subsequent in date but positive, of the guilt of Dreyfus, and this proof he had had before his eyes; it was a paper in which the attaché "A" wrote to the attaché "B": "Never mention the dealings we have had with this Jew."

General Gonse immediately confirmed this sensational evidence. This was the first time that the document forged by Henry — the "thunderbolt" of Billot — had been publicly produced. The impression this admission created was intense. Labori protested against this garbled quotation, and demanded that the document should either be brought before the court or should not be used at all. Then Pellieux, turning toward an orderly officer, cried: "Take a cab, and go and fetch General de Boisdeffre." While waiting for the head of the staff the hearing was adjourned; it was arranged not to resume it that day, for in the interval the government, informed of the incident, had opposed the production of a document which brought the foreign embassies into the case, and of which Hanotaux, the minister for foreign affairs, warned by the Italian ambassador, Tornielli, suspected the genuineness. At the next day's hearing Boisdeffre was content with confirming the deposition of Pellieux on every point as "accurate and authentic," and boldly put the question of confidence to the jury. The president declared the incident closed.

Picquart, questioned by the lawyers, declared that he considered the document a forgery. Pellieux described him scornfully as "a gentleman who still bore the uniform of the French army and who dared charge three generals with a forgery". The jury, deliberating under fear of physical violence, declared the defendants guilty without extenuating circumstances. In consequence Zola was condemned to the maximum punishment: one year's imprisonment and a fine of 3,000 francs. The publisher of "L'Aurore" — defended by Georges Clémenceau — was sentenced to four months' imprisonment and a similar fine (February 23, 1898). The prisoners appealed to the Court of Cassation for annulment of the judgment. Contrary to their expectation and to that of the public the Criminal Court admitted the plea on the formal ground that the complaint should have been lodged by the court martial which had been slandered, and not by the minister of war.

The sentence was annulled on April 2. Chambaraud, the judge-advocate, and Manau, the attorney-general, made it clear that proceedings should not resume, at the same time showing a discreet sympathy for the cause of revision. The War Office, urged on by the deputies, had gone too far to draw back. The court martial, immediately assembled, decided to lodge a civil complaint. This time only three lines from the article were retained as count of the indictment, and the case was deferred to the Court of Assizes of Seine-et-Oise at Versailles. Zola protested against the competence of this court, but the Court of Cassation overruled him. The case was not called until July 18, under a new ministry. At the last moment Zola declared he would not appear, and fled to England to avoid hearing the sentence, which would then become final. The court condemned him to the maximum punishment, the same as that pronounced by the jury of the Seine. His name was also struck off the list of the Legion of Honour. The experts, on their part, slandered by him, brought an action against him which ended in his being condemned to pay 30,000 francs ($6,000) damages.

Political aspects of the "Affaire"

The different parties in the Chamber of Deputies began to make the most of the "affaire" for their political ends. A small phalanx of Socialists grouped round Jean Jaurès, who was more clear-sighted than his colleagues, and accused the government of delivering the republic up to the generals. A more numerous group of Radicals with "Nationalist" tendencies reproached them, on the contrary, with not having done what was necessary to defend the honour of the army. The chief spokesman of this group was Eugène Godefroy Cavaignac, descended from a former candidate for the presidency of the republic, and himself suspected of a similar ambition. Between these two shoals the premier Méline steered his course, holding fast to the principle of "respect for the judgment pronounced." Prudently refusing to enter into the discussion of the proofs of Dreyfus' guilt, he gave satisfaction to the anti-Revisionists by energetically denouncing the Revisionists. Cavaignac called upon the government to publish a document "both decisive and without danger" — the alleged report of Gonse upon the supposed avowals of Dreyfus to Lebrun-Renault. Méline declined to follow this track, which he called "la revision à la tribune." After a violent debate, the Chamber decided in Méline's favor (24 January). Again, on 12 February, in response to a question concerning "his dealings with the Dreyfus family," General Billot declared that if the revision took place he would not remain a moment longer at the War Office.

On 24 February the ministry were challenged as to the attitude which certain generals had assumed during the Zola trial. Méline, without approving of the errors of speech, explained them as the natural result of the exasperation caused by such an incessant campaign of invective and outrage. But this campaign was about to end: "It must absolutely cease!" he cried, with the applause of the Chamber, and he gave it to be understood that the mad obstinacy of the "intellectuels", as the advocates of revision were contemptuously called, would only end in bringing about a religious persecution. At the same time he made known a whole series of disciplinary measures demanded by circumstances. By the end of January a council of inquiry had declared for Colonel Picquart's retirement on account of his professional indiscretions in connection with Leblois. The ministerial decision had been left in suspense. it is easy to understand in whose interest — during the Zola trial; now it was put into execution, and Picquart's name was struck off the army list. His "accomplice" Leblois was dismissed from his duties as "maire adjoint," and suspended for six months from the practice of his profession as a lawyer.

During the four months which followed the first verdict against Zola, the only effect of the Revisionists' campaign was to divide French society. On the one side were the army, the leading classes, and the "social forces"; on the other, a handful of intellectuals and Socialists. Nationalism resumed its sway, associated with anti-Semitism, and the streets of Algiers were filled with blood. The battle continued in the press, and the League of the Rights of Man (president, Senator Trarieux) united the revisionists. From a judicial point of view all the avenues seemed barred. Apart from the epilogue of the Zola trial, only two cases, which received scant notice, looked encouraging. On the one hand, Colonel Picquart, having vainly sought military justice, had decided to lay a complaint before a civil court against the unknown authors of the forged "Speranza" letter and of the forged telegrams which he had received in Tunis. On the other hand, a cousin of Major Esterhazy, Christian Esterhazy, lodged a complaint against his relative, who, under pretense of investing their money "with his friend Rothschild," had swindled Christian and his mother. The same examining magistrate, Bertulus, was entrusted with the two cases; each threw light upon the other. Christian had been one of the intermediate agents in the collusion between Esterhazy and his protectors in the Staff Office, and he divulged some edifying details on this subject.

In the month of May, elections took place. The new Chamber was as mixed in its representation as its predecessor, with the addition of a few more Nationalists and anti-Semites. It did not include a single open Dreyfusard. During the electoral period the attitude of all parties had been to keep silent on the "affaire" and to exaggerate their enthusiasm for the army; later on, a few provincial councils called for strong measures against the agitators. At its first meeting with the Chamber Méline's ministry was put in the minority, and a Radical cabinet was formed (June 30), with Henri Brisson as president; he had failed as candidate for the presidency of the Chamber. Brisson remained completely unacquainted with the "affaire"; but his minister of war was Godefroy Cavaignac, who would be of use to him as a security with regard to the Nationalists, and leave him full power on this delicate question.

References

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Joseph Jacobs (1901–1906). "Dreyfus Case (L'Affaire Dreyfus)". In Singer, Isidore; et al. Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls Company.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Joseph Jacobs (1901–1906). "Dreyfus Case (L'Affaire Dreyfus)". In Singer, Isidore; et al. Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls Company.