Tours Amphitheatre

Galery of the west vomitorium | |

Tours Amphitheatre Shown within France | |

| Location |

Caesarodunum (Gallia Lugdunensis) modern-day Tours, Centre-Val de Loire |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 47°23′43.52″N 0°41′45.25″E / 47.3954222°N 0.6959028°ECoordinates: 47°23′43.52″N 0°41′45.25″E / 47.3954222°N 0.6959028°E |

| Type | Ancient Roman amphitheatre |

| Length |

122 meters (1st stage) 156 meters (expanded) |

| Width |

94 meters (1st stage) 134 meters (expanded) |

| Height | over 5 meters (expanded) |

| History | |

| Material | Soil and masonry |

| Founded |

c. 50 A.D. (1st stage) c. 150 AD (expanded) c. 250 (fortification) c. 360 (castrum added) |

| Cultures | Roman Empire |

| Site notes | |

| Condition | Ruins, incorporated into the existing buildings, walls, roads and cellars. |

| Public access | Limited to public areas (some roads and walls) |

| Capacity 14,000 (1st stage); 34,000 (expanded) | |

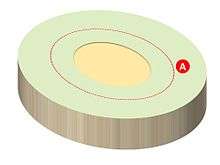

The Tours amphitheater — also known as the Caesarodunum amphitheater — is a Roman amphitheatre located in the historic city center of Tours, France, immediately behind the well known Tours cathedral. It was built in the 1st century when the city was called Caesarodunum. It was built atop a small hill on the outskirts of the ancient urban area, making it safe from floods, convenient for crowds and visitors, and demonstrating the power of the city from a distance. The structure was an enormous, elliptical structure approximately 122 meters by 94 meters. According to its design it is classified as a "primitive" amphitheatre. Unlike the famous Colosseum that was made mostly of masonry and built above-ground, the Tours amphitheatre was made mostly of earth and created by moving soil and rock into a bowl shape. Spectators likely sat directly on the grassy slopes, while the masonry was primarily used for the vomitoria and retaining walls.

When it was expanded in the 2nd century (to 156 m X 134 m), it became one of the largest structures (among the top ten) in the Roman Empire. It is not clear why the amphitheater was expanded given the population and slow growth of the city at the time. About a century later, this expanded amphitheatre was transformed into a fortress, with an addition of a rampart style wall, typical during the decline of Roman Empire. It gradually fell into ruin during the Middle Ages and canonical houses were built upon it and gradually concealed it. The vomitoria were at some point transformed into cellars.

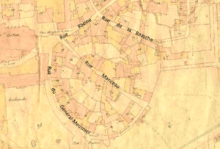

The amphitheater was then completely forgotten until the 19th century, when it was rediscovered (1855). Evidence such as the layout of the streets and radiating lots of the district drew attention to its existence. Surveys and terrain analyses in the 1960s gathered further data on the cellars of the houses which were previously built on the amphitheater walls. Over the past decade, more in-depth studies of the topography and architecture have taken place and are changing the theories and opinions surrounding this monument.

The remains of the amphitheater are not protected as historic sites directly; however, some of the houses built upon it are registered as historical monuments. The ruins of the amphitheater are significant as they are among the oldest known ruins in the city and offer clues about the early history and development of the area.

The amphitheater in the ancient city

Tours at the height of the Roman Empire

The city of Tours (known as Caesarodunum in Roman times) was established in the valley between Loire and Cher rivers, probably during the reign of Augustus or Tiberius (between 10 BC and 30 AD). The ancient city was at least 80 hectares in size and heavily populated along the Loire River. Discoveries thus far indicate that it had at least one temple, two spas, two aqueducts, bridges and an amphitheater. The city reached its peak at the height of the Roman Empire in the second century before shrinking, during the decline of the Western Roman Empire to the area in and around a Roman castrum whose amphitheater is one of the structural parts.

The site of the amphitheatre

The amphitheater was built in the suburbs at the northeast part of the ancient city, immediately southeast of the existing cathedral. The choice of this site corresponds to both the urban planning of the time and the layout of the land. Archaeologists believe the amphitheater was built on a natural sedimentary rock hill, which minimized masonry work by having it partially built into the rock. Being the middle of a low-lying flood plain, this also provided flood protection. The urban planning was such that the amphitheater had to accommodate large numbers of spectators, from within and outside the city and had to allow space for crowds around the monument. Given the size of this initial urban footprint, it is estimated that the population of the city was about 6000 people when the amphitheatre was constructed. The high ground upon which the amphitheater was built also allowed for the demonstration of wealth and power from a distance, a characteristic that was considered very important in the urban planning decisions of the Roman Empire.

History

Studies conducted up to the late 1970s presented an image of a monument that was relatively homogeneous in its construction, built in a single period (early second century). Research of the twenty-first century, however has presented a different picture. The current theory is that the amphitheater was originally built in the first century and then altered at two separate times; first it was altered by expansion in the second century creating an amphitheatre almost twice the size. It was again altered in the third century, permanently transforming it into a fortification. This fortification would then serve as a starting point for an even larger enclosed area, known as a castrum, that would be built around 350 A.D.

The original amphitheater

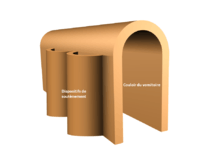

The Tours amphitheater is classified as a "primitive" amphitheatre, based on its design, not necessarily its age. It is as large as the amphitheatres in Samarobriva (Amiens), Octodurus (Martigny, Switzerland) or Emerita Augusta (Mérida, Spain). Another characteristic these amphitheatres share is that the cavea is not contained in the radiating walls and arches, as is seen in the Nîmes Arena, but rather within an outside embankment that slopes towards the arena. In Tours, the excavation of land in the arena during the original construction helped form this embankment. Spectators likely sat directly on the grassy slope of the embankment, but it is possible wooden bleachers (yet to be discovered) may have been used. Another primitive feature is the lack of stone steps and minimal masonry employed. For example, masonry was primarily used for the outer wall, the arena wall, galleries or vomitoria, and some radiating retaining walls.

The dimensions of this pseudo-elliptical amphitheater in the first phase of its existence, are valued at 112 meters for the major axis and 94 meters for the minor axis . Its estimated area is 8,270 meters2. This is based on research as of 2014. The dimensions of the arena were approximately 68 meters by 50 meters with an area of 2670 m2. The 5600 m2 of the cavea could accommodate at least 14,000 spectators. The structure had eight vomitoria, four of which were the primary entrances and allowed access at the arena level as well as a higher level of the cavea. The other four were secondary, leading to the middle part of the cavea via stairs. The north and south vomitoria had a vault height of about 7.5 meters and a width of 4.9 meters; vomitoria on the west were smaller, measuring only 6.8 meters high and 2.5 m wide. There were likely eight additional entrances, as it likely had a double exterior staircase at the front of the amphitheater similar to the amphitheatre of Pompeii. The orientation of the amphitheater was deliberately aligned with the city's street plan: its minor axis continues towards the west, along the Decumanus Maximus of the city, while its long axis is parallel to Cardo.

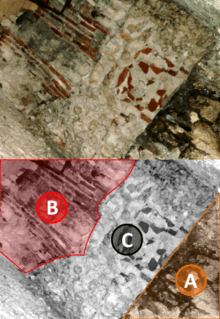

The entrances were paired vomitoria assembled into large blocks with sharp joints, the piers were topped with molded capitals that support a semicircular arch. The ramparts of Tours, made later during the falling Roman Empire, has many blocks that were likely reused from the amphitheater facade. The rest of the masonry of the walls and vaults of the amphitheater, was likely built from small rubble limestone cement (opus vittatum) without inclusion of terracotta, enclosing the stone blocks in concrete.

The construction dates back to the second half of the first century, or at least fifty years after the founding of Caesarodunum (Tours). It was at this time that most ancient monuments of Tours were likely built. This is based on the comparison of the architectural elements of the amphitheater of Tours and those of Amiens, Autun or Saintes, three monuments which have been precisely dated.

Amphitheatre expansion

The characteristics of the masonry (e.g. wall thickness was only 1.4 meters) indicate that the amphitheatre was in expanded in the second half of the second century. While the overall dimensions of the amphitheater exceeded 156 × 134 meters, the size of the arena itself did not change. The capacity, however, more than doubled, having increased to allow for about 34,000 spectators. In this configuration, the amphitheater was extended in its southwestern part, beyond the existing retaining wall of the Général-Meusnier Street, thought to be the outer wall of the structure. The height of the amphitheater was estimated to be about 25 to 28 meters in the 1970s. More recent discoveries, however suggest this values is closer to between 15 and 18 meters.

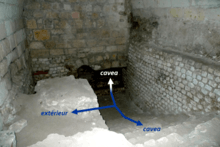

There are numerous hints that show that the expansion was a renovation project. For example, the width and height of the main vomitoria vary significantly at the junction of two phases of work; two half-diameter reinforcements were built on either side of the entrances to increase the load bearing capacity (see Fig. 1), given the increased height (and weight) along the edge where the mass backfill rose sharply.

These construction features have been identified, in several points of the amphitheater and it is not yet possible to say if this same pattern occurred to the entire monument.

During the expansion, the external staircases of the original amphitheater were found embedded in the new embankment. Without being abandoned, they may have been vaulted and connected to the main vomitoria, becoming intermediate steps. Secondary vomitoria do not appear to have been extended to the new facade by corridors, but they may have been connected to a circular gallery on the ground floor. There is no direct evidence that new outside stairs were placed against the front wall, however there is indirect evidence to suggest that there were once stairs. For example, the cutaway front is attributed to towers made at the time of construction of the castrum. Also, the front wall seems devoid of any decorative element, based on the few remains available for observation.

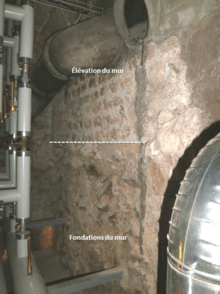

Fortified amphitheatre

In the second half or towards the end of the third century, the upper part of the cavea was 8 meters above the level of the arena. An annular wall was constructed without the use of quoin tiling and without large recycled stone blocks (from other dismantled buildings) included in its foundations. It was therefore constructed prior to the castrum, who saw these techniques implemented. The stone mixture of the wall was comparable to the enlarged amphitheater, however the wall obliterated some of its structures, indicating it was made after those structures. With a thickness of 3.5 meters and a height probably above the level of the cavea, the defensive wall was placed continuous along the entire on the embankment. This hypothesis is supported by the fact that the side vomitoria and indoor stairs were completely blocked, leaving the main vomitoria as the only access to the arena (facilitating defence). Moreover, there was a defensive moat preceded by a counterscarp, dated from the second half of the third century and dug at the foot of the amphitheater. While the remains were discovered in the southeast part of the structure, it was probably completely encircled the amphitheatre. Its maintenance ceased with the building of the castrum.

Comparable stone masonry, dating from the same period, exist in Avenches (Switzerland), Lillebonne and the arenas of Senlis. In each case the massive character of a monument, theater or amphitheater, was converted into a fort and offered temporarily shelter to nearby residents in case of attack. This would have been far less labour-intensive than building a fort from scratch.

This construction was definitely spread out over a period of several months, likely in response to a deterioration of some kind with the security and safety of the city inhabitants. The inhabitants at the time would have known that this was a permanent change to the amphitheater, rendering it ineffective in its original function of displaying performances.

Building the castrum to the amphitheatre

In a context of growing insecurity and retreat from the city to the more densely settled neighborhoods near the Loire River, Caesarodunum, which gradually took on the name of Civitas Turonorum around 360 A.D. and rose to the rank of capital city of the Roman province of Gallia Lugdunensis, and built the defensive wall, usually referred to as a castrum. This castrum was built around the same time as first Tours cathedral (located in the castrum, at the south-west angle).

The evidence from excavations carried out in different points of the enclosure of the castrum and systematic reviews of previous work show that outer wall was well constructed against the amphitheater and extended from its location. Many clues support this thesis. For example, the amphitheater is situated exactly in the middle of the south wall. Also the west, south and east vomitoria, which were outside the defended area, remained in service and may have been converted into a formal castrum entrance as was the case in Trier. Moreover, the main path leading to the west vomitorium (similar to the decumanus maximus of the city in the first century, the street location of Scellerie) continues outside the castrum and serves as an alignment to the south castrum wall. Already naturally well defended by its high structure during its conversion in the third century, the amphitheater was did not have an apron wall during the construction of the castrum: no additional protection wall is plastered on the outer surface.

Other cities of Gaul have also used their amphitheater as a defensive element of an enclosure during the 3rd century. For example, the amphitheaters of Périgueux, Amiens, Metz and Trier, were ideal for conversion into a fortification. What is striking in the case of Tours is the perfectly symmetrical positioning of the amphitheater in the heart of the new town plans and the geometry of the enclosure, only disturbed by the Loire River which washed the base of the north wall.

The amphitheatre lost during the Middle Ages

In the ninth century, a section of the front of the amphitheater that had long since collapsed, was repaired with large blocks borrowed from a public building, probably located in the castrum, which had stood since the height of the Roman Empire and also towers may have been built against the front of the amphitheater in the southern half during this time. These projects were likely on the orders of Charles the Bald who, in 869, ordered that the walls of several cities, including Tours are repaired to protect against the Norman raids. A charter of Charles the Simple dated 919 mentions the amphitheater, in the context of a land exchange in a place called "Arenas" (the Arena). This is the last explicit mention of the presence of the amphitheatre, the ruins of which were perhaps still visible in the undeveloped part of the city.

The development of the canonical quarter in the Middle Ages lead to the use of the amphitheatre substructures to support the foundations and cellars of canon houses. These homes were reserved for the canons of the Cathedral Chapter from 1250 A.D. (the time of construction of the new Gothic cathedral), until the French Revolution. At that time, former vomitoria, that were then mainly underground, were transformed into cellars and partitioned by walls, their length, their width and sometimes even in their height, leading to several levels of basements. The development of the area becomes apparent, however, still with a lot of open spaces (two documents of the thirteenth century mentioned vineyards and stables). Despite the conversion of vomitoria as basements, no further reference is made to the ancient monument as the whole area is finally slowly consumed by homes and the remains of the amphitheater were no longer visible.

After the Revolution, the houses in the neighborhood were no longer reserved for canons, however the topography had undergone only very slight modifications since. If the walls of the houses were partially removed, the foundations would essentially remain in place. The amphitheater was completely forgotten up until the nineteenth century, but was rediscovered in 1855 thanks to the actions undertaken by the Archaeological Society of Touraine.

Unanswered questions

Uncertainties still remain about the appearance of the building, its structure and precise dimensions. Beyond these architectural unknown, there are other questions that also remain.

The nature of the shows held by the Tours amphitheater is still not determined. It can be assumed that, like the other arenas of the Roman Empire, including Gaul, that there were gladiator fights (as was the case in Bourges) and executions of convicts (as occurred in Lyon or in Trier). No stone inscription, text, or other clues have been discovered that could provide answers.

The rationale for the construction of such a large structure in a medium-sized city, has been debated since the 1970s and is still not known. While the amphitheater's capacity more than doubled, no known event warranted such an effort. In fact, some evidence suggests that the population of Caesarodonum (Tours) had stopped growing by that time. In its final state, the amphitheater of Tours was among the greatest of the Roman Empire with dimensions comparable structures of Autun, Italica (Spain), Capua (Italy) and Carthage (Tunisia); cities whose political weight and height significantly overshadowed those of Caesarodonum. One theory was a desire for emulation among the Gallo-Roman cities, and that they were eager to show their power by building larger, higher, ediface as a civitas.

Finally, the source of financing, building, and maintaining such a structure remains an enigma. Spectacular monuments of the time were frequently offered to towns by wealthy citizens, who had financed the construction, however this practice of euergetism in Tours has not been proven thus far by any source. Moreover, during this period of slow economic growth it is difficult to see who had the fortune necessary for this costly project and who would benefit from such an undertaking.

| Dimensions of the largest amphitheatres of the Roman Empire | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Colosseum (Rome, Italy) | 188 × 156 m | ||

| Capua (Italy) | 167 × 137 m | ||

| Italica (Spain): | 157 × 134 m | ||

| Tours | 156 × 134 m | ||

| Carthage (Tunisia) | 156 × 128 m | ||

| Autun | 154 × 130 m | ||

| Nîmes | 133 × 101 m | ||

Remains and research

Remains of the amphitheatre

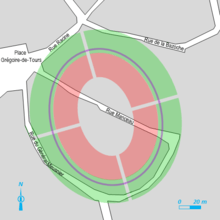

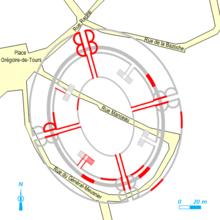

An aerial view over the city and streets provides the best overview of the amphitheater of Tours. Rue Manceau ("Manceau Street") descends from the edge of the old cavea from the southeast to the arena and divides it. Rue du Général-Meusnier follows the curve of the amphitheater, from the northwest part to the southeast. The rue Racine and the rue de la Bazoche form a tangential straight line at the north-west and north-east points of the monument's perimeter. Examination of cadastral maps, Napoleonic (1836 A.D.) or modern is even more suggestive, as parcesl of land display a radiant profile and emphasizes the layout of the amphitheater. Similarly, the part corresponding to the cavea was almost entirely developed prior to the development of the large plot of land remaining at the ancient arena.

The difference in height between rue de la Porte-Rouline and rue du Général- Meusnier (approximately 5 meters), which is best viewed behind the Studios cinemas, demonstrates the minimum height of the amphitheatre. In fact, the height of the amphitheater was certainly much higher but the centuries have worn down a part of the step and gradually leveled the monument with the accumulation of debris at its foot.

Close examination of the remains of the building (Figure II) requires access to private property in the neighborhood and their cellars, however, behind the Departmental Archives building, a court allows public access to the front wall of the enlarged amphitheater. The massive nature of the amphitheater may explain the scarcity of the remains, and this scarcity has contributed to the preservation of the remaining masonry embedded in the embankment.

The remains of the Tours Gallo-Roman amphitheater is listed in Table I. As of 2014, none of these remains were subject to protection as a historical monument, or by registration or by classification. The protective measures mentioned in references in the table apply only to the height, roofs or the decoration of the houses concerned, but not to their foundations, which are seated on the ruins of the amphitheater. These are, however, preserved by the town's conservation area.[Note 1] Similarly, the perimeter and the Cathedral area, of which the amphitheater is part, is a historic site under the Law of 2 May 1930, and by the Decree of June 7, 1944.

| Address or location | Description of the remains |

|---|---|

| 3, rue de la Bazoche | Wall of north vomitorium (O, A) Reinforcing pillar(A) |

| 5, rue de la Bazoche | Wall of north vomitorium (O, A)

Reinforcing pillar (A) |

| 7, rue de la Bazoche | Stairs of outer wall (O) Fortification wall (F) |

| 5, rue Racine | Gallery of the north vomitorium (O, A) Reinforcing pillar(A) |

| Dividing wall between 5 and 7, rue Racine | Wall of north vomitorium |

| 4, rue du Général-Meusnier | Outer wall (O) Reinforcing pillar of the west vomitorium (A) |

| 6, rue du Général-Meusnier | Gallery of the west vomitorium (O, A) |

| 8, rue du Général-Meusnier | Gallery of the west vomitorium (O, A) |

| 10, rue du Général-Meusnier | Stairs of the south-west vomitorium (O) |

| 12, rue du Général-Meusnier[1] | South-west vomitorium (O) Stairs of the South-west vomitorium (O) |

| Bedside the Vincentian chapel, rue du General Meusnier |

Outer wall (O) |

| 14, rue du Général-Meusnier | Gallery of the south vomitorium (O, A) |

| 1, rue Manceau[2] | Wall of north-west vomitorium (O) |

| 3, rue Manceau[3] | Arena wall (O) |

| 4, rue Manceau | Gallery of the north vomitorium (O, A) |

| 4bis, rue Manceau | Gallery of the east vomitorium (O, A) Fortification wall (F) |

| 5, rue Manceau | Arena wall (O) |

| 6, rue Manceau | Gallery of the east vomitorium (A) Fortification wall (F) |

| 8, rue Manceau | Outer wall of amphitheatre (A) |

| 11, rue Manceau | Gallery of the south-east vomitorium (O) Outer wall of amphitheatre (O) |

| 13, rue Manceau | Outer wall of amphitheatre (O) Fortification wall (F) |

| Court of departmental archives, rue des Ursulines |

Repair blocks of the facade of the enlarged amphitheater |

| Abbreviations

(O) Original amphitheatre; (A) amphitheatre addition; (F) fortified amphitheatre | |

- The Tours amphitheatre in the roads and buildings of the city.

-

.jpg)

La rue du Général-Meusnier as seen from the north-west.

-

La rue Manceau as seen from the north-west. The arena indicated in red.

-

.jpg)

La rue de la Porte-Rouline as seen from the south.

-

The terrace of the archbishop.

-

.jpg)

The courtyard of Studio cinemas

References

Bibliography

Documents used as a source for this article.

Specific papers on the archeology and history of Touraine

- Pierre Audin, Tours à l'époque gallo-romaine, Saint-Cyr-sur-Loire, Alan Sutton, , 128 p. (ISBN 2 842 53748 3).

- baron Henry Auvray, « La Touraine gallo-romaine ; l'amphithéâtre », Bulletin de la Société Archéologique de Touraine, t. XXVII, 1938-1939, p. 235-250 (lire en ligne).

Patrick Bordeaux et Jacques Seigne, « Les amphithéâtres antiques de Tours », Bulletin de la Société Archéologique de Touraine, t. LI, , p. 51-62 (lire en ligne).

- Bernard Chevalier (dir.), Histoire de Tours, Toulouse, Privat, coll. « Univers de la France et des pays francophones », , 423 p. (ISBN 2 708 98224 9).

- Jean-Mary Couderc, La Touraine insolite - 2e série, Chambray-lès-Tours, , 236 p. (ISBN 2 854 43211 8).

- Claude Croubois (dir.), L’indre-et-Loire – La Touraine, des origines à nos jours, Saint-Jean-d’Angely, Bordessoules, coll. « L’histoire par les documents », , 470 p. (ISBN 2 90350 409 1).

- Jacques Dubois et Jean-Paul Sazerat, « L’Amphithéâtre de Tours », Mémoire de la Société Archéologique de Touraine, t. VIII, , p. 41–74.

- Jacques Dubois et Jean-Paul Sazerat, « L’Amphithéâtre de Tours, recherches récentes », Bulletin de la Société Archéologique de Touraine, t. XXXVIII, , p. 355-378 (lire en ligne).

Henri Galinié (dir.), Tours antique et médiéval. Lieux de vie, temps de la ville. 40 ans d'archéologie urbaine, 30e supplément à la Revue archéologique du centre de la France (RACF), numéro spécial de la collection Recherches sur Tours, Tours, FERACF, , 440 p. (ISBN 978 2 91327 215 6).

Bastien Lefebvre, La formation d’un tissu urbain dans la Cité de Tours : du site de l’amphithéâtre antique au quartier canonial (5e-18e s.), Tours, Université François-Rabelais, Thèse de doctorat en histoire, mention archéologie, , 443 p. (lire en ligne).

- Michel Provost, Carte archéologique de la Gaule - l'Indre-et Loire-37, Paris, Académie des inscriptions et belles-lettres, , 141 p. (ISBN 2 87754 002 2).

Jason Wood (trad. de l'anglais par Bernard Randoin), Le castrum de Tours, étude architecturale du rempart du Bas-Empire, vol. 2, Joué-lès-Tours, la Simarre, coll. « Recherches sur Tours », .

General works totally or partially devoted to architecture of the Roman Empire

Robert Bedon, Pierre Pinon et Raymond Chevallier, Architecture et urbanisme en Gaule romaine : L'architecture et la ville, vol. 1, Paris, Errance, coll. « les Hespérides », , 440 p. (ISBN 2 903 44279 7).

- Jean-Claude Golvin, L'amphithéâtre romain et les jeux du cirque dans le monde antique, Archéologie nouvelle, coll. « Archéologie vivante », , 152 p. (ISBN 978 2 95339 735 2).

See also

External links

- Site de la Société archéologique de Touraine

- Site de l'Institut national de recherches archéologiques préventives (INRAP)

Notes and references

Notes

- ↑ Dans le secteur sauvegardé de Tours de « niveau A », où se trouvent les vestiges du l'amphithéâtre, tous les travaux affectant le bâti (démolition, construction, aménagement), autres que ceux touchant les toitures et le ravalement d'immeubles récents et quelle qu'en soit l'importance, doivent faire l'objet d'une demande préalable auprès du préfet de région pour « instructions et prescriptions archéologiques éventuelles » (Plan de sauvegarde et de mise en valeur du secteur sauvegardé de la ville de Tours, zones archéologiques[PDF]).

References

- Pierre Audin, Tours à l'époque gallo-romaine, 2002 :

- Robert Bedon, Pierre Pinon et Raymond Chevallier, Architecture et urbanisme en Gaule romaine ; Volume 1 : l'architecture et la ville, 1988 :

- Patrick Bordeaux et Jacques Seigne, Les amphithéâtres antiques de Tours, 2005 :

- Henri Galinié (dir.), Tours antique et médiéval. Lieux de vie, temps de le ville. 40 ans d'archéologie urbaine, 2007 :

- Jean-Claude Golvin, L'amphithéâtre romain et les jeux du cirque dans le monde antique, 2012 :

- Bastien Lefebvre, La formation d’un tissu urbain dans la Cité de Tours : du site de l’amphithéâtre antique au quartier canonial (5e-18e s.), 2008 :

- Autres références :

- ↑ Immeuble inscrit Monument historique : « Notice no PA00098231 », base Mérimée, ministère français de la Culture.

- ↑ Immeuble inscrit Monument historique : « Notice no PA00098200 », base Mérimée, ministère français de la Culture.

- ↑ Immeuble inscrit Monument historique : « Notice no PA00098201 », base Mérimée, ministère français de la Culture.

|}