Pitcairn Islands

| Pitcairn, Henderson, Ducie and Oeno Islands Pitkern Ailen |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||

| Anthem: "Come Ye Blessed"[1] "We from Pitcairn Islands" Royal anthem: "God Save the Queen" |

||||||

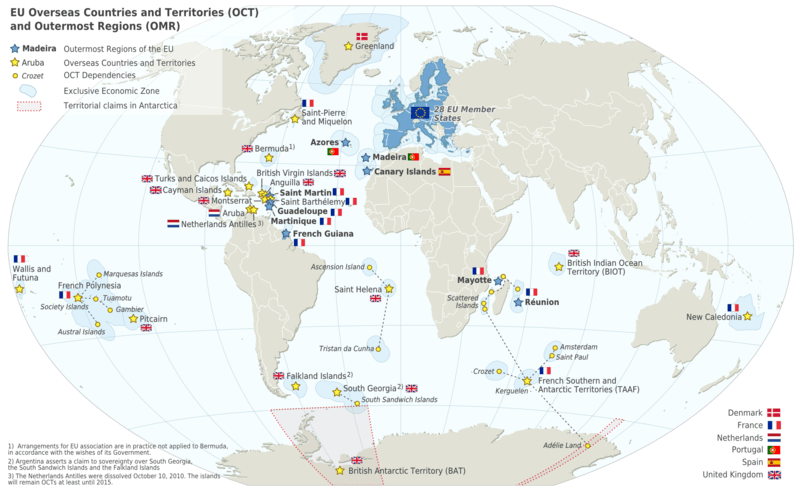

.svg.png) Location of Pitcairn Islands (circled in red) in the Pacific Ocean (light blue) |

||||||

| Status | British Overseas Territory | |||||

| Capital | Adamstown 25°04′S 130°06′W / 25.067°S 130.100°W | |||||

| Languages | English, Pitcairnese | |||||

| Ethnic groups | ||||||

| Religion | Seventh-day Adventist (not established by law, but virtually the entire population follows it) | |||||

| Demonym | Pitcairn Islander[2] | |||||

| Government | Parliamentary dependency under constitutional monarchy | |||||

| • | Monarch | Elizabeth II | ||||

| • | Governor | Jonathan Sinclair | ||||

| • | Administrator | Alan Richmond | ||||

| • | Mayor | Shawn Christian | ||||

| • | Responsible Ministera (UK) | James Duddridge MP | ||||

| Legislature | Island Council | |||||

| Area | ||||||

| • | Total | 47 km2 18.1 sq mi |

||||

| Population | ||||||

| • | 2014 estimate | 49[3] (last) | ||||

| • | 2010 census | 45 | ||||

| • | Density | 1.19/km2 (240th) 3.09/sq mi |

||||

| GDP (nominal) | 2005 estimate | |||||

| • | Total | NZ$ 217 000[4] | ||||

| Currency | New Zealand dollarb (NZD) | |||||

| Time zone | UTC-8 | |||||

| Calling code | +64 | |||||

| ISO 3166 code | PN | |||||

| Internet TLD | .pn | |||||

| a. | For the Overseas Territories. | |||||

| b. | The Pitcairn Islands dollar is treated as a collectible/souvenir currency outside Pitcairn. US Dollar also widely accepted due to cruise ships.[5] UK Postcode: PCRN 1ZZ |

|||||

The Pitcairn Islands (/ˈpɪtkɛərn/;[6] Pitkern: Pitkern Ailen) or officially Pitcairn, Henderson, Ducie and Oeno Islands,[7][8][9][10] are a group of four volcanic islands in the southern Pacific Ocean that form the last British Overseas Territory in the Pacific. The four islands – Pitcairn, Henderson, Ducie, and Oeno – are spread over several hundred miles of ocean and have a total land area of about 47 square kilometres (18 sq mi). Only Pitcairn, the second-largest island that measures about 3.6 kilometres (2.2 mi) from east to west, is inhabited.

The islands are inhabited mostly by descendants of the Bounty mutineers and the Tahitians (or Polynesians) who accompanied them, an event retold in numerous books and films. This history is still apparent in the surnames of many of the islanders. With only about 50 permanent inhabitants, originating from four main families,[3] Pitcairn is the least populous national jurisdiction in the world.[11] The United Nations Committee on Decolonization includes the Pitcairn Islands on the United Nations list of Non-Self-Governing Territories.[12]

History

Polynesian settlement and extinction

The earliest known settlers of the Pitcairn Islands were Polynesians who appear to have lived on Pitcairn and Henderson, as well as Mangareva Island 400 kilometres (250 mi) to the northwest, for several centuries. They traded goods and formed social ties among the three islands despite the long canoe voyages between them, helping the small populations on each island survive despite their limited resources. Eventually, important natural resources were exhausted, inter-island trade broke down and a period of civil war began on Mangareva, causing the small human populations on Henderson and Pitcairn to be cut off and eventually become extinct.

Although archaeologists believe that Polynesians were living on Pitcairn as late as the 15th century, the islands were uninhabited when they were rediscovered by Europeans.[13]

European discovery

Ducie and Henderson Islands were discovered by Portuguese sailor Pedro Fernandes de Queirós, sailing for the Spanish Crown, who arrived on 26 January 1606. He named them La Encarnación ("The Incarnation") and San Juan Bautista ("Saint John the Baptist"), respectively. However, some sources express doubt about exactly which of the islands were visited and named by Queirós, suggesting that La Encarnación may actually have been Henderson Island, and San Juan Bautista may have been Pitcairn Island.[14]

Pitcairn Island was sighted on 3 July 1767 by the crew of the British sloop HMS Swallow, commanded by Captain Philip Carteret. The island was named after Midshipman Robert Pitcairn, a fifteen-year-old crew member who was the first to sight the island. Robert Pitcairn was a son of British Marine Major John Pitcairn, who later was killed at the Battle of Bunker Hill in the American Revolution.

Carteret, who sailed without the newly invented accurate marine chronometer, charted the island at 25°2′S 133°21′W / 25.033°S 133.350°W, and although the latitude was reasonably accurate, the longitude was incorrect by about 3° (330 km). This made Pitcairn difficult to find, as highlighted by the failure of Captain James Cook to locate the island in July 1773.[15][16]

European settlement

In 1790 nine of the mutineers from the Bounty, along with the native Tahitian men and women who were with them (six men, eleven women and a baby girl), settled on Pitcairn Islands and set fire to the Bounty. The wreck is still visible underwater in Bounty Bay, discovered in 1957 by National Geographic explorer Luis Marden. Although the settlers survived by farming and fishing, the initial period of settlement was marked by serious tensions among them. Alcoholism, murder, disease and other ills took the lives of most mutineers and Tahitian men. John Adams and Ned Young turned to the scriptures, using the ship's Bible as their guide for a new and peaceful society. Young eventually died of an asthmatic infection. The Polynesians also converted to Christianity. They later converted from their original form of Christianity to Seventh-day Adventism, following a successful Adventist mission in the 1890s. After the rediscovery of Pitcairn, John Adams was granted amnesty for his part in the mutiny.[17]

Ducie Island was rediscovered in 1791 by Royal Navy Captain Edwards aboard HMS Pandora, while searching for the Bounty mutineers. He named it after Francis Reynolds-Moreton, 3rd Baron Ducie, also a captain in the Royal Navy.

The Pitcairn islanders reported it was not until 27 December 1795 that the first ship since the Bounty was seen from the island, but it did not approach the land and they could not make out the nationality. A second ship appeared in 1801, but made no attempt to communicate with them. A third came sufficiently near to see their house, but did not try to send a boat on shore. Finally, the American sealing ship Topaz under Mayhew Folger became the first to visit the island, when the crew spent 10 hours on Pitcairn in February 1808. A report of Folger's discovery was forwarded to the Admiralty, mentioning the mutineers and giving a more precise location of the island: 25°2′S 130°0′W / 25.033°S 130.000°W.[18] However this was not known to Sir Thomas Staines, who commanded a Royal Navy flotilla of two ships (HMS Briton and HMS Tagus) which found the island at 25°4′S 130°25′W / 25.067°S 130.417°W (by meridian observation) on 17 September 1814. Staines sent a party ashore and wrote a detailed report for the Admiralty.[17][19][20][21]

Henderson Island was rediscovered on 17 January 1819 by British Captain James Henderson of the British East India Company ship Hercules. Captain Henry King, sailing on the Elizabeth, landed on 2 March to find the king's colours already flying. His crew scratched the name of their ship into a tree. Oeno Island was discovered on 26 January 1824 by American Captain George Worth aboard the whaler Oeno.

In 1832 a Church Missionary Society missionary, Joshua Hill, arrived; he reported that by March 1833 he had founded a Temperance Society to combat drunkenness, a 'Maundy Thursday Society', a monthly prayer meeting, a juvenile society, a Peace Society and a school.[22]

British colony

Pitcairn Island became a British colony in 1838,[2] and was among the first territories to extend voting rights to women. By the mid-1850s, the Pitcairn community was outgrowing the island. Its leaders appealed to the British government for assistance, and were offered Norfolk Island. On 3 May 1856 the entire population of 193 people set sail for Norfolk on board the Morayshire, arriving on 8 June after a miserable five-week trip. However, after 18 months on Norfolk, 17 of the Pitcairners decided to return to their home island; five years later another 27 followed.[17]

In 1886 the Seventh-day Adventist layman John Tay visited the island and persuaded most of the islanders to accept his faith. He returned in 1890 on the missionary schooner Pitcairn with an ordained minister to perform baptisms. Since then, the majority of Pitcairners have been Adventists.[23]

Henderson, Oeno and Ducie islands were annexed by Britain in 1902: Henderson on 1 July, Oeno on 10 July and Ducie on 19 December.[24] In 1938 the three islands, along with Pitcairn, were incorporated into a single administrative unit called the "Pitcairn Group of Islands".

The population peaked at 233 in 1937 and has since fallen owing to emigration, primarily to New Zealand.[2]

Sexual assault trials of 2004

In 2004, charges were laid against seven men living on Pitcairn and six living abroad. This accounted for nearly a third of the male population. After extensive trials, most of the men were convicted, some with multiple counts of sexual encounters with children.[25] On 25 October 2004, six men were convicted, including Steve Christian, the island's mayor at the time.[26][27][28] After the six men lost their final appeal, the British government set up a prison on the island at Bob's Valley.[29][30] The men began serving their sentences in late 2006. By 2010, all had served their sentences or been granted home detention status.[31]

In 2010 the then mayor Mike Warren faced 25 charges of possessing images and videos of child pornography on his computer.[32][33]

An "entry clearance application" must be made for any child under the age of 16, prior to visiting Pitcairn, while adults visiting the island for periods of less than 14 days are not required to complete any application or visa request prior to arrival.[34]

As of 2016, The UK's Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) does not allow their staff based on Pitcairn to be accompanied by their children.[34]

Geography

The Pitcairn Islands form the southeasternmost extension of the geological archipelago of the Tuamotus of French Polynesia, and consist of four islands: Pitcairn Island, Oeno Island (atoll with five islets, one of which is Sandy Island), Henderson Island and Ducie Island (atoll with four islets).

The Pitcairn Islands were formed by a centre of upwelling magma called the Pitcairn hotspot.

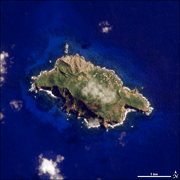

The only permanently inhabited island, Pitcairn, is accessible only by boat through Bounty Bay. Henderson Island, covering about 86% of the territory's total land area and supporting a rich variety of animals in its nearly inaccessible interior, is also capable of supporting a small human population despite its scarce fresh water, but access is difficult, owing to its outer shores being steep limestone cliffs covered by sharp coral. In 1988, this island was designated as a UNESCO World Heritage site.[35] The other islands are at a distance of more than 100 km (62 mi) and are not habitable.

| Island or atoll | Type | Land area (km2) | Total area (km2) | Pop. July 2011 | Coordinates |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ducie Island | Atoll[lower-alpha 1] | 0.7 | 3.9 | 0 | 24°40′09″S 124°47′11″W / 24.66917°S 124.78639°W |

| Henderson Island | Uplifted coral island | 37.3 | 37.3 | 0 | 24°22′01″S 128°18′57″W / 24.36694°S 128.31583°W |

| Oeno Island | Atoll[lower-alpha 1] | 0.65 | 16.65 | 0 | 23°55′26″S 130°44′03″W / 23.92389°S 130.73417°W |

| Pitcairn Island | Volcanic island | 4.6 | 4.6 | 68 | 25°04′00″S 130°06′00″W / 25.06667°S 130.10000°W |

| Pitcairn Islands (all islands) | – | 43.25 | 62.45 | 68 | 23°55′26″ to 25°04′00″S, 124°47′11″ to 130°44′03″W |

Pitcairn Island as seen from a globe view with other Pacific Islands.

Pitcairn Island as seen from a globe view with other Pacific Islands. Satellite photo of Pitcairn Island

Satellite photo of Pitcairn Island Map of Pitcairn Islands

Map of Pitcairn Islands View of Bounty Bay

View of Bounty Bay

Climate

Pitcairn is located just south of the Tropic of Capricorn and enjoys year-round warm weather, with wet summers and drier winters. The rainy season is from November through to March; summer is from April to October, when temperatures average 25 to 35 °C (77 to 95 °F) and humidity averages can exceed 95%. Temperatures in the winter range from 17 to 25 °C (63 to 77 °F).[2]

Flora

About nine plant species are thought to occur only on Pitcairn. These include tapau, formerly an important timber resource, and the giant nehe fern. Some, such as red berry (Coprosma rapensis var. Benefica), are perilously close to extinction.[36] The plant species Glochidion pitcairnense is endemic to Pitcairn and Henderson Islands.[37]

Fauna

Between 1937 and 1951, Irving Johnson, skipper of the 29-metre (96 ft) brigantine Yankee Five, introduced five Galápagos giant tortoises to Pitcairn. Turpen, also known as Mr. Turpen or Mr. T, is the sole survivor. Turpen usually lives at Tedside by Western Harbour. A protection order makes it an offence should anyone kill, injure, capture, maim, or cause harm or distress to the tortoise.[38]

The birds of Pitcairn fall into several groups. These include seabirds, wading birds and a small number of resident land-bird species. Of 20 breeding species, Henderson Island has 16, including the unique flightless Henderson crake; Oeno hosts 12; Ducie 13 and Pitcairn six species. Birds breeding on Pitcairn include the fairy tern, common noddy and red-tailed tropicbird. The Pitcairn reed warbler, known by Pitcairners as a "sparrow", is endemic to Pitcairn Island; formerly common, it was added to the endangered species list in 2008.[39]

Important bird areas

The four islands in the Pitcairn group have been identified by BirdLife International as separate Important Bird Areas (IBAs). Pitcairn Island itself is recognised because it is the only nesting site of the Pitcairn reed warbler. Henderson Island is important for its endemic land-birds as well as its breeding seabirds. Oeno's ornithological significance derives principally from its Murphy's petrel colony. Ducie is important for its colonies of Murphy's, herald and Kermadec petrels, and Christmas shearwaters.[40]

Pitcairn Islands Marine Reserve

In March 2015 the British government established the largest continuous marine protected area in the world around the Pitcairn Islands. The reserve covers the islands' entire exclusive economic zone – 834,334 square kilometres (322,138 sq mi) – more than three times the land area of the British Isles. The intention is to protect some of the world's most pristine ocean habitat from illegal fishing activities. A satellite "watchroom" dubbed Project Eyes on the Seas has been established by the Satellite Applications Catapult and the Pew Charitable Trusts at the Harwell Science and Innovation Campus in Harwell, Oxfordshire to monitor vessel activity and to gather the information needed to prosecute unauthorised trawling. [41][42][43][44]

Politics

The Pitcairn Islands are a British overseas territory with a degree of local government. The Queen of the United Kingdom is represented by a Governor, who also holds office as British High Commissioner to New Zealand and is based in Auckland.[45]

The 2010 constitution gives authority for the islands to operate as a representative democracy, with the United Kingdom retaining responsibility for matters such as defence and foreign affairs. The Governor and the Island Council may enact laws for the "peace, order and good government" of Pitcairn. The Island Council customarily appoints a Mayor of Pitcairn as a day-to-day head of the local administration. There is a Commissioner, appointed by the Governor, who liaises between the Council and the Governor's office.

The Pitcairn Islands has the smallest population of any democracy in the world.

Military

The Pitcairn Islands are an overseas territory of the United Kingdom; defence is the responsibility of the Ministry of Defence and Her Majesty's Armed Forces.[2] In 2004, the islanders had about 20 guns among them, which they surrendered ahead of the sexual assault trials.[46]

Economy

Agriculture

The fertile soil of the Pitcairn valleys, such as Isaac's Valley on the gentle slopes southeast of Adamstown, produces a wide variety of fruits: including bananas (Pitkern: plun), papaya (paw paws), pineapples, mangoes, watermelons, cantaloupes, passionfruit, breadfruit, coconuts, avocadoes, and citrus (including mandarin oranges, grapefruit, lemons and limes). Vegetables include: sweet potatoes (kumura), carrots, sweet corn, tomatoes, taro, yams, peas, and beans. Arrowroot (Maranta arundinacea) and sugarcane are grown and harvested to produce arrowroot flour and molasses, respectively. Pitcairn Island is remarkably productive and its benign climate supports a wide range of tropical and temperate crops.[47]

Fish are plentiful in the seas around Pitcairn. Spiny lobster and a large variety of fish are caught for meals and for trading aboard passing ships. Almost every day someone will go fishing, whether it is from the rocks, from a longboat or diving with a spear gun. There are numerous types of fish around the island. Fish such as nanwee, white fish, moi and opapa are caught in shallow water, while snapper, big eye and cod are caught in deep water, and yellow tail and wahoo are caught by trawling. A range of minerals—including manganese, iron, copper, gold, silver and zinc—have been discovered within the Exclusive Economic Zone, which extends 370 km (230 mi) offshore and comprises 880,000 km2 (340,000 sq mi).[48]

Honey production

In 1998 the UK's overseas aid agency, the Department for International Development, funded an apiculture programme for Pitcairn which included training for Pitcairn's beekeepers and a detailed analysis of Pitcairn's bees and honey with particular regard to the presence or absence of disease. Pitcairn has one of the best examples of disease-free bee populations anywhere in the world and the honey produced was and remains exceptionally high in quality. Pitcairn bees are also a placid variety and, within a short time, beekeepers are able to work with them wearing minimal protection.[49] As a result, Pitcairn exports honey to New Zealand and to the United Kingdom. In London, Fortnum & Mason sells it and it is a favourite of Queen Elizabeth and Prince Charles.[50] The Pitcairn Islanders, under the "Bounty Products" and "Delectable Bounty" brands, also export dried fruit including bananas, papayas, pineapples and mangoes to New Zealand.[51]

Tourism

Tourism plays a major role on Pitcairn, providing the locals with 80% of their annual income. Tourism is the focus for building the economy. It focuses on small groups coming by charter vessel and staying at "home stays". About ten times a year, passengers from expedition-type cruise ships come ashore for a day, weather permitting.[34][52] Since 2009, the government has been operating the MV Claymore II as the island's only dedicated passenger/cargo vessel, providing adventure tourism holidays to Pitcairn for three-day or ten-day visits. Tourists stay with local families and experience the island's culture while contributing to the local economy. Providing accommodation is a growing source of revenue, and some families have invested in private self-contained units adjacent to their homes for tourists to rent.

Each year up to ten cruise ships call at the island for a few hours (weather permitting), generating income for the locals from the sale of souvenirs, and for the government from landing fees and the stamping of passports. Children under 16 require a completed entry clearance application to visit the island.[34]

Lesser revenue sources

The Pitcairners are involved in creating crafts and curios (made out of wood from Henderson). Typical woodcarvings include sharks, fish, whales, dolphins, turtles, vases, birds, walking sticks, book boxes, and models of the Bounty. Miro (Thespesia populnea), a dark and durable wood, is preferred for carving. Islanders also produce tapa cloth and painted Hattie leaves.[53] The major sources of revenue, until recently, have been the sale of coins and postage stamps to collectors, .pn domain names, and the sale of handicrafts to passing ships, most of which are on the United Kingdom to New Zealand route via the Panama Canal.[54]

Electricity

Diesel generators provide the island with electricity from 8 am to 1 pm, and from 5 pm to 10 pm. A wind power plant was planned to be installed to help reduce the high cost of power generation associated with the import of diesel, but was cancelled in 2013 after a project overrun of three years and a cost of £250,000.[55]

The only qualified high voltage electricity technician on Pitcairn, who manages the electricity grid, reached the age of 65 in 2014.[3]

Demographics

The islands have suffered a substantial population decline since 1940, and the viability of the island's community is in doubt (see § Potential extinction, below). In recent years, the government has been trying to attract new migrants. However, these initiatives have not been effective.[56]

As of 2012, just two children had been born on Pitcairn in the 21 years prior.[57] In 2005, Shirley and Simon Young became the first married outsider couple in history to obtain citizenship on Pitcairn.[58]

Language

Most resident Pitcairn Islanders are descendants of the Bounty mutineers and Tahitians (or other Polynesians). Pitkern is a creole language derived from 18th-century English, with elements of the Tahitian language.[2][35] It is spoken as a first language by the population and is taught alongside English at the island's only school. It is closely related to the creole language Norfuk, spoken on Norfolk Island, because Norfolk was repopulated in the mid-19th century by Pitcairners.

Religion

The entire population is Seventh-day Adventist.[2] The Seventh-Day Adventist Church is not a state religion, as no laws concerning its establishment were passed by the local government. A successful Seventh-day Adventist mission in the 1890s was important in shaping Pitcairn society. In recent years, the church has declined, and as of 2000, eight of the then forty islanders attended services regularly,[59] but most attend church on special occasions. From Friday at sunset until Saturday at sunset, Pitcairners observe a day of rest in observance of the Sabbath, or as a mark of respect for observant Adventists.

The church was built in 1954 and is run by the Church board and resident pastor, who usually serves a two-year term. The Sabbath School meets at 10 am on Saturday mornings, and is followed by Divine Service an hour later. On Tuesday evenings, there is another service in the form of a prayer meeting.

Education

Education is free and compulsory between the ages of five and sixteen.[60] All of Pitcairn's seven children were enrolled in school in 2000.[60] The island's children have produced a book in Pitkern and English called Mi Bas Side orn Pitcairn or My Favourite Place on Pitcairn.

The school at Pitcairn provides pre-school and primary education based on the New Zealand syllabus. The teacher is appointed by the governor from suitable qualified applicants who are New Zealand registered teachers. The contract includes the role of editor of the Pitcairn Miscellany.

The Pitcairn Island Economic Report assumes that in around 2015–2016 there will not be any pre-school children and that the children who leave for New Zealand at age 15 for the last years of schooling are unlikely to return.[3]

Historical population

Pitcairn's population has drastically decreased since its peak of over 250 in 1936 to 56 in 2014.[61]

| Year | Population | Year | Population | Year | Population | Year | Population | Year | Population | Year | Population |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1790 | 27 | 1880 | 112 | 1970 | 96 | 1992 | 54 | 2002 | 48 | 2012 | 48 |

| 1800 | 34 | 1890 | 136 | 1975 | 74 | 1993 | 57 | 2003 | 59 | 2013 | 56 |

| 1810 | 50 | 1900 | 136 | 1980 | 61 | 1994 | 54 | 2004 | 65 | 2014 | [lower-roman 1]56 |

| 1820 | 66 | 1910 | 140 | 1985 | 58 | 1995 | 55 | 2005 | 63 | ||

| 1830 | 70 | 1920 | 163 | 1986 | 68 | 1996 | 43 | 2006 | 65 | ||

| 1840 | 119 | 1930 | 190 | 1987 | 59 | 1997 | 40 | 2007 | 64 | ||

| 1850 | 146 | 1936 | 250 | 1988 | 55 | 1998 | 66 | 2008 | 66 | ||

| 1856 | [lower-roman 2]193 | 1940 | 163 | 1989 | 55 | 1999 | 46 | 2009 | 67 | ||

| 1859 | [lower-roman 3]16 | 1950 | 161 | 1990 | 59 | 2000 | 51 | 2010 | 64 | ||

| 1870 | 70 | 1960 | 126 | 1991 | 66 | 2001 | 44 | 2011 | 67 |

Potential extinction

As of July 2014, the total resident population of the Pitcairn Islands was 56, including the six temporary residents: an administrator, doctor, and police officer and each of their spouses.[62] However, the actual permanent resident population was only 49 Pitcairners spread across 23 households.[3] It is, however, rare for all 49 residents to be on-island at the same time; it is common for several residents to be off-island for varying lengths of time visiting family, for medical reasons, or to attend international conferences. As of November 2013 for instance, seven residents were off-island.[3] A diaspora survey projected that by 2045, if nothing were done, only three people of working age would be left on the island, with the rest being very old. In addition, the survey revealed that residents who had left the island over the past decades showed little interest in coming back. Of the hundreds of emigrants contacted, only 33 were willing to participate in the survey and just 3 expressed a desire to return.

As of 2014, the labour force consisted of 31 able-bodied persons: 17 males and 14 females between 18 and 64 years of age. Of the 31, just seven are younger than 40, but 18 are over the age of 50.[3] Most of the men undertake the more strenuous physical tasks on the island such as crewing the longboats, cargo handling, and the operation and maintenance of physical assets. Longboat crew retirement age is 58. There were then 12 men aged between 18 and 58 residing on Pitcairn. Each longboat requires a minimum crew of three; of the four longboat coxswains, two were in their late 50s.[3]

The Pitcairn government's attempts to attract migrants have been unsuccessful. Since 2013, some 700 make inquiries each year, but so far, not a single formal settlement application has been received.[3][56] The new migrants are prohibited from taking local jobs or claiming benefits for a certain length of time, even those with children.[63] The migrants are expected to have at least NZ$ 30 000 per person in savings and are expected to build their own house at average cost of NZ$ 140 000.[64][65] It is also possible to bring the off-island builders at the additional cost between NZ$ 23 000 and NZ$ 28 000.[65] The average annual cost of living on the island is NZ$ 9464.[64] There is, however, no assurance of the migrant's right to remain on Pitcairn; after their first two years, the council must review and reapprove the migrant's status.[66] The migrants are also required to take part in the unpaid public work to keep the island in order: maintain the island's numerous roads and paths, build roads, navigate the island longboats, clean public toilets etc.[67] There are also restrictions on bringing children under the age of 16 to the island.[32][68]

Freight from Tauranga to Pitcairn on the MV Claymore II (Pitcairn Island's dedicated passenger and cargo ship chartered by the Pitcairn government) is charged at NZ$ 350/m3 for Pitcairners and NZ$ 1000/m3 for all other freight.[69] Additionally, Pitcairners are charged NZ$ 3000 for a one-way trip; others are charged NZ$ 5000.[3]

In 2014, the 2014 government's Pitcairn Islands Economic Report stated[3] that "[no one] will migrate to Pitcairn Islands for economic reasons as there are limited government jobs, a lack of private sector employment, as well as considerable competition for the tourism dollar".[3] The Pitcairners take tourists in turns to accommodate those few tourists who occasionally visit the island.[3]

As the island remains a British Overseas Territory, at some point the British government may have to make a decision about the island's future.[70][71]

Culture

The once-strict moral codes, which prohibited dancing, public displays of affection, smoking, and consumption of alcohol, have been relaxed. Islanders and visitors no longer require a six-month licence to purchase, import, and consume alcohol.[72] There is now one licensed café and bar on the island, and the government store sells alcohol and cigarettes.

Fishing and swimming are two popular recreational activities. A birthday celebration or the arrival of a ship or yacht will involve the entire Pitcairn community in a public dinner in the Square, Adamstown. Tables are covered in a variety of foods, including fish, meat, chicken, pilhi, baked rice, boiled plun (banana), breadfruit, vegetable dishes, an assortment of pies, bread, breadsticks, an array of desserts, pineapple and watermelon.

Public work ensures the ongoing maintenance of the island's numerous roads and paths. As of 2011, the island had a labour force of over 35 men and women.[2]

Since 2015, same-sex marriage became legal on Pitcairn Island, but there are no known such people or couples on the island.[73]

Media and communications

- Telephones

- Pitcairn uses New Zealand's international calling code, +64. It is still on the manual telephone system.

- Radio

- There is no broadcast station. Marine band walkie-talkie radios are used to maintain contact among people in different areas of the island. Foreign stations can be picked up on shortwave radio.

- Amateur Radio

- QRZ.COM lists six amateur radio operators on the island, using the ITU prefix (assigned through the UK) of VP6. Some of those operators have now died while others are no longer active. The last DX-pedition to Pitcairn took place in 2012.[74] In 2008, a major DX-pedition visited Ducie Island.[75]

- Television

- There are two live TV channels available via Trans-Pacific satellite, CNN, and Turner Classic Movies. Free-to-air satellite dishes can be used to watch foreign TV.

- Internet

- There is one government-sponsored satellite internet connection, with networking provided to the inhabitants of the island. Pitcairn's country code (top level domain) is .pn. Residents pay NZ$ 100 (about £50) for 2 GB of data per month, at a rate of 256 kbit/s.[76] The Pitcairn Miscellany reports that despite the bandwidth recently being doubled to 512 kbit/s this is not per user but is in fact shared among all families on the island, making normal internet use extremely difficult.

Transport

All settlers of the Pitcairn Islands initially arrived by boat or ship. Pitcairn Island does not have an airport, airstrip or seaport;[34] the islanders rely on longboats to ferry people and goods between visiting ships and shore through Bounty Bay. Access to the rest of the shoreline is restricted by jagged rocks. The island has one shallow harbour with a launch ramp accessible only by small longboats.[77]

A dedicated passenger/cargo supply ship chartered by the Pitcairn Island government, the MV Claymore II, is the principal transport from Mangareva, Gambier Islands, French Polynesia; although passage can also be booked through Pitcairn Travel, Pitcairn's locally owned tour operators who charter the SV Xplore, owned by Stephen Wilkins, which also departs from Mangareva.

Totegegie Airport in Mangareva can be reached by air from the French Polynesian capital Papeete.[78]

There is one 6.4-kilometre (4 mi) paved road leading up from Bounty Bay through Adamstown.

The main modes of transport on Pitcairn Islands are by four-wheel drive quad bikes and on foot.[34] Much of the road and track network and some of the footpaths of Pitcairn Island are viewable on Google's Street View.[79][80]

Notable people

On 20 September 1793, Fletcher Christian died here at age 28.[81]

Gallery

Bounty Bay in the 1970s

Bounty Bay in the 1970s Pitcairn landing site

Pitcairn landing site Pitcairn Island

Pitcairn Island- Henderson Island shelter

Oeno

Oeno St. Paul's Point in west Pitcairn Island

St. Paul's Point in west Pitcairn Island Garnets Ridge, Pitcairn Island

Garnets Ridge, Pitcairn Island

See also

- Law enforcement in the Pitcairn Islands

- Mutiny on the Bounty

- Bibliography of Pitcairn Islands

- Bounty Bible

- Bounty Day

- Island Council (Pitcairn)

- List of islands

- Outline of the Pitcairn Islands

- Thursday October Christian I

References

- ↑ "Pitcairn Islands". nationalanthems.info.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "CIA World Factbook: Pitcairn Islands". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 26 February 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Rob Solomon and Kirsty Burnett (January 2014) Pitcairn Island Economic Review. government.pn.

- ↑ "Pitcairn Islands Strategic Development Plan, 2012–2016" (PDF). The Government of the Pitcairn Islands. 2013. p. 4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 July 2015.

Gross Domestic Product (GDP) . . . NZ$ 217,000 (2005/06 indicative estimate) and NZ$ 4,340 per capita (based on 50 residents)

- ↑ http://www.demtullpitcairn.com/2016JanFebMarch.pdf

- ↑ Oxford English Dictionary

- ↑ "British Nationality Act 1981 – SCHEDULE 6 British Overseas Territories". UK Government. September 2016.

- ↑ "Pitcairn Constitution Order 2010 – Section 2 and Schedule 1, Section 6" (PDF). UK Government. September 2016.

- ↑ "Laws of Pitcairn, Henderson, Ducie and Oeno Islands". Pitcairn Island Council. September 2016.

- ↑ "The Overseas Territories" (PDF). UK Government. September 2016.

- ↑ Country Comparison: Population. The World Factbook.

- ↑ "United Nations list of Non-Self-Governing Territories". United Nations. Retrieved 4 July 2015.

- ↑ Diamond, Jared M (2005). Collapse: how societies choose to fail or succeed. New York: Penguin. p. 132. ISBN 9780143036555. OCLC 62868295.

But by A.D. 1606 . . . Henderson's population had ceased to exist. Pitcairn's own population had disappeared at least by 1790 . . . and probably disappeared much earlier.

- ↑ "History of Government and Laws, Part 15 History of Pitcairn Island". Pitcairn Islands Study Centre. Archived from the original on 11 December 2014. Retrieved 4 July 2015.

- ↑ Brian Hooker. "Down with Bligh: hurrah for Tahiti". Finding New Zealand. Archived from the original on 26 May 2010. Retrieved 4 July 2015.

- ↑ Winthrop, Mark. "The Story of the Bounty Chronometer". Lareau Web Parlour. Archived from the original on 5 September 2009. Retrieved 4 July 2015.

- 1 2 3 "Pitcairn's History". The Government of the Pitcairn Islands. Archived from the original on 17 December 2014. Retrieved 4 July 2015.

- ↑ "Mutineers of the Bounty". The European Magazine, and London Review. Philological Society of London,. 69: 134. January–June 1816.,

- ↑ The Annual Biography and Obituary for the Year . . ., Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, and Brown, 1831, Volume 15 "Chapter X Sir Thomas Staines" pp. 366–367

- ↑ History of Pitcairn Island, Pitcairn Islands Study Centre. Retrieved 15 September 2008.

- ↑ "Pitcairn descendants of the Bounty Mutineers". Jane's Oceania. 29 April 2009. Archived from the original on 14 August 2015.

- ↑ CMS archives, University of Birminghamm G/AC/15/75, quoted in Wolffe, John. The expansion of evangelicalism: The age of Wilberforce, More, Chalmers and Finney. Vol. 2. InterVarsity Press, 2007

- ↑ IBP USA (1 August 2013). Pitcairn Islands Business Law Handbook. International Business Publications. p. 92. ISBN 9781438770796. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- ↑ Ben Cahoon. "Pitcairn Island". worldstatesmen.org. Retrieved 4 July 2010.

- ↑ Tweedie, Neil (5 October 2004). "Islander changes his plea to admit sex assaults". The Telegraph. London. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ↑ Fickling, David (25 October 2004). "Six found guilty in Pitcairn sex offences trial: Defendants claim British law does not apply". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 2 July 2015.

- ↑ "Six guilty in Pitcairn sex trial". BBC News. 25 October 2004. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ↑ "6 men convicted in Pitcairn trials". The New York Times. 24 October 2004. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ↑ Marks, Kathy (25 May 2005). "Pitcairners stay free till British hearing". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ↑ Marks, Kathy (2009). Lost Paradise: From Mutiny on the Bounty to a Modern-Day Legacy of Sexual Mayhem, the Dark Secrets of Pitcairn Island Revealed. Simon and Schuster. p. 288. ISBN 9781416597841.

- ↑ "Last Pitcairn rape prisoner released". The Sydney Morning Herald. 23 April 2009. Archived from the original on 2 July 2015. Retrieved 4 July 2015.

- 1 2 Gay, Edward (11 March 2013). "Pitcairn Island mayor faces porn charges in court". The New Zealand Herald.

- ↑ R v Michael Warren (Court of Appeal of the Pitcairn Islands 2012). Text

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Foreign travel advice: Pitcairn. Foreign and Commonwealth Office. (6 December 2012). Retrieved 29 August 2016.

- 1 2 Editors of Encyclopædia Britannica, The (2015). "Pitcairn Island: Island, Pacific Ocean". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ↑ S. Waldren and N. Kingston (1998). Coprosma rapensis var. benefica. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.

- ↑ S. Waldren and N. Kingston (1998). Glochidion pitcairnense. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.

- ↑ Endangered Species Protection Ordinance, 2004 revised edition. government.pn

- ↑ BirdLife International (2014). Acrocephalus vaughani. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.

- ↑ BirdLife International. (2012). Important Bird Areas factsheet: Pitcairn Island.

- ↑ Gauke, David, ed. (2015). "2.259 Marine Protected Area (MPA) at Pitcairn" (PDF). Budget 2015: The Red Book (PDF). London: HM Treasury. p. 97. ISBN 978-1-4741-1616-9. OCLC 907644530. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 October 2015.

The government intends to proceed with designation of [an] MPA around Pitcairn. This will be dependent upon reaching agreement with NGOs on satellite monitoring and with authorities in relevant ports to prevent landing of illegal catch, as well as on identifying a practical naval method of enforcing the MPA at a cost that can be accommodated within existing departmental expenditure limits.

- ↑ Amos, Jonathan (18 March 2015). "Budget 2015: Pitcairn Islands get huge marine reserve". BBC News. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ↑ "Pew, National Geographic Applaud Creation of Pitcairn Islands Marine Reserve" (Press release). London: The Pew Charitable Trusts. 18 March 2015. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ↑ Clark Howard, Brian (18 March 2015). "World's Largest Single Marine Reserve Created in Pacific". National Geographic. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ↑ "Home." Government of the Pitcairn Islands. Retrieved 31 October 2011.

- ↑ "Pitcairn islanders to surrender guns". Television New Zealand. Reuters. 11 August 2004. Archived from the original on 17 March 2015. Retrieved 4 July 2015.

- ↑ Secretariat of the Pacific Community (SPC): Pitcairn Islands-Joint Country Strategy, 2008.

- ↑ Commonwealth Secretariat; Rupert Jones-Parry (2010). "Pitcairn Economy". The Commonwealth Yearbook 2010. Commonwealth Secretariat. ISBN 9780956306012.

- ↑ Laing, Aislinn (9 January 2010). "Sales of honey fall for the first time in six years amid British bee colony collapse". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 3 January 2015.

- ↑ Carmichael, Sri (8 January 2010). "I'll let you off, Mr Christian: you make honey fit for a queen". London Evening Standard. Retrieved 3 January 2015.

- ↑ Pitcairn Islands Study Center, News Release: Products from Pitcairn, 7 November 1999.

- ↑ Pitcairn Island Report prepared by Jaques and Associates, 2003, p. 21.

- ↑ Foreign and Commonwealth Office, Profile on Pitcairn Islands, British Overseas Territory, 11 February 2010.

- ↑ Pitcairn Island Report prepared by Jaques and Associates, 2003, p. 18.

- ↑ "UK aid wasted on South Pacific windfarm fiasco: failed green energy scheme for only 55 people cost £250,000". Daily Mail. 8 April 2013. Retrieved 4 July 2015.

- 1 2 "Pitcairn Island, an idyll haunted by its past". Toronto Star. 16 December 2013.

- ↑ Ford, Herbert, ed. (30 March 2007). "News Releases: Pitcairn Island Enjoying Newest Edition [sic]". Pitcairn Islands Study Center. Angwin, California: Pacific Union College. Archived from the original on 12 October 2008.

- ↑ Pitcairn Miscellany, March 2005.

- ↑ "Turning Point for Historic Adventist Community on Pitcairn Island". Adventist News Network. Silver Spring, Maryland: General Conference of Seventh-day Adventists. 28 May 2001. Archived from the original on 19 October 2015.

Although the Adventist Church has always maintained a resident minister and nurse on Pitcairn, there have been fewer adherents and some church members have moved away from the island. By the end of 2000, regular church attendees among the island population of 40 numbered only eight.

- 1 2 "Territories and Non-Independent Countries". 2001 Findings on the Worst Forms of Child Labor. Bureau of International Labor Affairs, U.S. Department of Labor (2002). This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ↑ "Pitcairn Census". Pitcairn Islands Study Center. Retrieved 4 July 2015.

- ↑ "Pitcairn Residents". puc.edu.

- ↑ "Ch. XXII. Social Welfare Benefits Ordinance" in Laws of Pitcairn, Henderson, Ducie and Oeno Islands. Revised Edition 2014

- 1 2 Bill Haigh. "Pitcairn Island Immigration". immigration.pn.

- 1 2 kerry young, heather menzies. "Pitcairn Island Immigration Questions and Answers". young.pn.

- ↑ Ch. XII. "Immigration Control Ordinance" in Laws of Pitcairn, Henderson, Ducie and Oeno Islands. Revised Edition 2014

- ↑ Pitcairn Islands Repopulation Plan 2014–2019. The Pitcairn Islands Council

- ↑ "Pitcairn Island travel advice". gov.uk. UK government. Retrieved 6 September 2015.

- ↑ "Pitcairn Island Tourism: MV Claymore II Ship Info". visitpitcairn.pn.

- ↑ "Pitcairn Islands Face Extinction". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 3 December 2014.

- ↑ "South Pacific Island of 'Mutiny on the Bounty' Fame Running Out of People". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 3 December 2014.

- ↑ Pitcairn Island Government Ordinance. government.pn; Archive.org

- ↑ Press, Associated (22 June 2015). "Pitcairn Island, population 48, passes law to allow same-sex marriage".

- ↑ "VP6T: Pitcairn". g3txf.com.

- ↑ VP6DX: Ducie Island. Ducie2008.dl1mgb.com. Retrieved 20 September 2013.

- ↑ Slivka, Eric, "iPad Makes Its Way to the Farthest Reaches of the Earth" MacRumors.com. Retrieved 3 November 2010

- ↑ David H. Evans (2007) Pitkern Ilan = Pitcairn Island. Self-published, Auckland, p. 46

- ↑ Lonely Planet South Pacific, 3rd ed. 2006, "Pitcairn Getting There" pp. 429–430

- ↑ "Pitcairn News", 13 December 2013. Retrieved 13 February 2014

- ↑ "View from the end of St Pauls Point on Street View". Retrieved 13 February 2014

- ↑ Kirk, Robert W. (2012). "A White Tribe at Botany Bay, 1788–1911". Paradise Past: The Transformation of the South Pacific, 1520–1920. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company. p. 61. ISBN 978-0-7864-6978-9. LCCN 2012034746. OCLC 791643077.

Further reading

Mutiny on the Bounty

- Mutiny on the Bounty by Charles Nordhoff and James Norman Hall, 1932

- The Bounty: The True Story of the Mutiny on the Bounty by Caroline Alexander (Harper Perennial, London, 2003 pp. 491)

- The Discovery of Fletcher Christian: A Travel Book by Glynn Christian, a descendant of Fletcher Christian, Bounty Mutineer (Guild Press, London, 2005 pp. 448)

After the Mutiny

- Men Against the Sea by Charles Nordhoff and James Norman Hall, 1933

- Pitcairn's Island by Charles Nordhoff and James Norman Hall, 1934

- The Pitcairners by Robert B. Nicolson (Pasifika Press, Auckland, 1997 pp. 260)

- After the Bounty: The Aftermath of the Infamous Mutiny on the HMS Bounty—An Insight to the Plight of the Mutineers by Cal Adams, a descendant of John Adams, Bounty Mutineer (Self-published, Sydney, 2008 pp. 184)

- The "Re-colonising of Pitcairn by Sue Farran, Senior Lecturer, University of Dundee; Visiting Lecturer, University of the South Pacific.

External links

Government

Travel

- Pitcairn Island Tourism Official tourism site of the Pitcairn Islands.

-

Wikimedia Atlas of Pitcairn Islands

Wikimedia Atlas of Pitcairn Islands

Local news

- Pitcairn News from Big Flower News from Big Flower, Pitcairn Island.

- Pitcairn Miscellany News from Pitcairn Island. Jacqui Christian, ed.

- Pitcairn News information from Chris Double, a Bounty descendant based in Auckland

- Uklun Tul Un Dem Tul Pitcairn news by Kari Young, a Pitcairn resident.

Study groups

- The Pitcairn and Norfolk Islands Society

- U.S. Pitcairn Islands Study Centre

- U.S. Pitcairn Islands Study Group

Coordinates: 25°04′S 130°06′W / 25.067°S 130.100°W

.svg.png)