Domesticated turkey

| Domesticated turkey | |

|---|---|

| |

| A broad breasted bronze male (tom) displaying. | |

| Domesticated | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Galliformes |

| Family: | Meleagridinae |

| Genus: | Meleagris |

| Species: | M. gallopavo |

| Binomial name | |

| Meleagris gallopavo (Linnaeus, 1758) | |

The domesticated turkey (Meleagris gallopavo) is a large poultry bird, one of the two species in the genus Meleagris and the same as the wild turkey. Although turkey domestication was thought to have occurred in central Mesoamerica at least 2,000 years ago,[1] recent research suggests a possible second domestication event in the Southwestern United States between 200 BC - AD 500. However, all of the commercial domesticated turkey varieties today descend from the domesticated turkey raised in central Mexico that was subsequently imported into Europe by the Spanish in the 16th century.[2]

Turkey meat is a popular form of poultry, and turkeys are raised throughout temperate parts of the world, partially because industrialized farming has made it very cheap for the amount of meat it produces. Female domesticated turkeys are referred to as hens, and the chicks may be called poults or turkeylings. In the United States, the males are referred to as toms, while in Europe, males are stags.

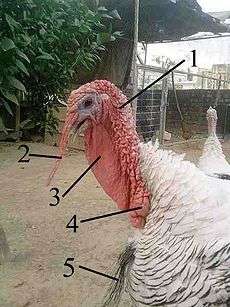

The great majority of domesticated turkeys is bred to have white feathers because their pin feathers are less visible when the carcass is dressed, although brown or bronze-feathered varieties are also raised. The fleshy protuberance atop the beak is the snood, and the one attached to the underside of the beak is known as a wattle.

The English language name for this species result from an early misidentification of the bird with an unrelated species which was imported to Europe through the country of Turkey.[3]

History

The modern domesticated turkey is descended from one of six subspecies of wild turkey: Meleagris gallopavo, found in the area bounded by the present Mexican states of Jalisco, Guerrero, and Veracruz[4] Ancient Mesoamericans domesticated this subspecies, using its meat and eggs as major sources of protein and employing its feathers extensively for decorative purposes. The Aztecs associated the turkey with their trickster god Tezcatlipoca,[5] perhaps because of its perceived humorous behavior.

Domestic turkeys were taken to Europe by the Spanish. Many distinct breeds were developed in Europe (e.g. Spanish Black, Royal Palm). In the early 20th century, many advances were made in the breeding of turkeys, resulting in breeds such as the Beltsville Small White.

The 16th-century English navigator William Strickland is generally credited with introducing the turkey into England.[6][7] His family coat of arms — showing a turkey cock as the family crest — is among the earliest known European depictions of a turkey.[6][8] English farmer Thomas Tusser notes the turkey being among farmer's fare at Christmas in 1573.[9] The domestic turkey was sent from England to Jamestown, Virginia in 1608. A document written in 1584 lists supplies to be furnished to future colonies in the New World; "turkies, male and female".[10]

Prior to the late 19th century, turkey was something of a luxury in the UK, with goose or beef a more common Christmas dinner among the working classes.[11] In Charles Dickens' A Christmas Carol (1843), Bob Cratchit had a goose before Scrooge bought him a turkey.[12]

Turkey production in the UK was centered in East Anglia, using two breeds, the Norfolk Black and the Norfolk Bronze (also known as Cambridge Bronze). These would be driven as flocks, after shoeing, down to markets in London from the 17th century onwards - the breeds having arrived in the early 16th century via Spain.[13]

Intensive farming of turkeys from the late 1940s dramatically cut the price, making it more affordable for the working classes. With the availability of refrigeration, whole turkeys could be shipped frozen to distant markets. Later advances in disease control increased production even more. Advances in shipping, changing consumer preferences and the proliferation of commercial poultry plants has made fresh turkey inexpensive as well as readily available.

Recent genome analysis has provided researchers with the opportunity to determine the evolutionary history of domesticated turkeys, and their relationship to other domestic fowl.[14]

Behaviour

Young domestic turkeys readily fly short distances, perch and roost. These behaviours become less frequent as the birds mature, but adults will readily climb on objects such as bales of straw. Young birds perform spontaneous, frivolous running ('frolicking') which has all the appearance of play. Commercial turkeys show a wide diversity of behaviours including 'comfort' behaviours such as wing-flapping, feather ruffling, leg stretching and dust-bathing. Turkeys are highly social and become very distressed when isolated. Many of their behaviours are socially facilitated i.e. expression of a behaviour by one animal increases the tendency for this behaviour to be performed by others. Adults can recognise 'strangers' and placing any alien turkey into an established group will almost certainly result in that individual being attacked, sometimes fatally. Turkeys are highly vocal, and 'social tension' within the group can be monitored by the birds’ vocalisations. A high-pitched trill indicates the birds are becoming aggressive which can develop into intense sparring where opponents leap at each other with the large, sharp talons, and try to peck or grasp the head of each other. Aggression increases in frequency and severity as the birds mature.

Maturing males spend a considerable proportion of their time sexually displaying. This is very similar to that of the wild turkey and involves fanning the tail feathers, drooping the wings and erecting all body feathers, including the 'beard' (a tuft of black, modified hair-like feathers on the centre of the breast). The skin of the head, neck and caruncles (fleshy nodules) becomes bright blue and red, and the snood (an erectile appendage on the forehead) elongates, the birds 'sneeze' at regular intervals, followed by a rapid vibration of their tail feathers. Throughout, the birds strut slowly about, with the neck arched backward, their breasts thrust forward and emitting their characteristic 'gobbling' call.

Size and weight

| Animal | Average mass kg (lb) |

Maximum mass kg (lb) |

Average total length cm (ft) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Domesticated turkey | 13.5 (29.8) [15] | 39 (86)[16] | 100 - 124.9 (3.3 – 4.1)[17] |

The domestic turkey is the eighth largest living bird species in terms of maximum mass at 39 kg (86 lbs).

Turkey breeds

- The Broad Breasted White is the commercial turkey of choice for large scale industrial turkey farms, and consequently is the most consumed variety of the bird. Usually the turkey to receive a "presidential pardon", a U.S. custom, is a Broad Breasted White.

- The Broad Breasted Bronze is another commercially developed strain of table bird.

- The Standard Bronze looks much like the Broad Breasted Bronze, except that it is single breasted, and can naturally breed.

- The Bourbon Red turkey is a smaller, non-commercial breed with dark reddish feathers with white markings.

- Slate, or Blue Slate, turkeys are a very rare breed with gray-blue feathers.

- The Black ("Spanish Black", "Norfolk Black") has very dark plumage with a green sheen.

- The Narragansett Turkey is a popular heritage breed named after Narraganset Bay in New England.

- The Chocolate is a rarer heritage breed with markings similar to a Black Spanish, but light brown instead of black in color. Common in the Southern U.S. and France before the Civil War.

- The Beltsville Small White is a small heritage breed, whose development started in 1934. The breed was introduced in 1941 and was admitted to the APA Standard in 1951. Although slightly bigger and broader than the Midget White, both are often mislabeled.

- The Midget White is a smaller heritage breed.

Commercial production

In commercial production, breeder farms supply eggs to hatcheries. After 28 days of incubation, the hatched poults are sexed and delivered to the grow-out farms; hens are raised separately from toms because of different growth rates.

In the UK, it is common to rear chicks in the following way. Between one and seven days of age, chicks are placed into small (2.5 m) circular brooding pens to ensure they encounter food and water. To encourage feeding, they may be kept under constant light for the first 48 hours. To assist thermoregulation, air temperature is maintained at 35 °C for the first three days, then lowered by approximately 3 °C every two days to 18 °C at 37 days of age, and infra-red heaters are usually provided for the first few days. Whilst in the pens, feed is made widely accessible by scattering it on sheets of paper in addition to being available in feeders. After several days, the pens are removed, allowing the birds access to the entire rearing shed, which may contain tens of thousands of birds. The birds remain there for several weeks, after which they are transported to another unit.[18]

The vast majority of turkeys are reared indoors in purpose-built or modified buildings of which there are many types. Some types have slatted walls to allow ventilation, but many have solid walls and no windows to allow artificial lighting manipulations to optimise production. The buildings can be very large (converted aircraft hangars are sometimes used) and may contain tens of thousands of birds as a single flock. The floor substrate is usually deep-litter, e.g. wood shavings, which relies upon the controlled build-up of a microbial flora requiring skilful management. Ambient temperatures for adult domestic turkeys are usually maintained between 18 and 21 °C. High temperatures should be avoided because the high metabolic rate of turkeys (up to 69 W/bird) makes them susceptible to heat stress, exacerbated by high stocking densities.[18] Commercial turkeys are kept under a variety of lighting schedules, e.g. continuous light, long photoperiods (23 h), or intermittent lighting, to encourage feeding and accelerate growth.[19] Light intensity is usually low (e.g. less than one lux) to reduce feather pecking.

Rations generally include corn and soybean meal, with added vitamins and minerals, and is adjusted for protein, carbohydrate and fat based on the age and nutrient requirements. Hens are slaughtered at about 14–16 weeks and toms at about 18–20 weeks of age when they can weigh over 20 kg compared to a mature male wild turkey which weighs approximately 10.8 kg.[20]

Welfare concerns

Stocking density is an issue in the welfare of commercial turkeys and high densities are a major animal welfare concern. Permitted stocking densities for turkeys reared indoors vary according to geography and animal welfare farm assurance schemes. For example, in Germany, there is a voluntary maximum of 52 kg/m2 and 58 kg/m2 for males and females respectively. In the UK, the RSPCA Freedom Foods assurance scheme reduces permissible stocking density to 25 kg/m2 for turkeys reared indoors.[21] Turkeys maintained at commercial stocking densities (8 birds/m2; 61 kg/m2) exhibit increased welfare problems such as increases in gait abnormalities, hip and foot lesions, and bird disturbances, and decreased bodyweight compared with lower stocking densities.[22] Turkeys reared at 8 birds/m2 have a higher incidence of hip lesions and foot pad dermatitis than those reared at 6.5 or 5.0 birds/m2.[23] Insufficient space may lead to an increased risk for injuries such as broken wings caused by hitting the pen walls or other turkeys during aggressive encounters[24] and can also lead to heat stress.[25] The problems of small space allowance are exacerbated by the major influence of social facilitation on the behaviour of turkeys. If turkeys are to feed, drink, dust-bathe, etc., simultaneously, then to avoid causing frustration, resources and space must be available in large quantities.

Lighting manipulations used to optimise production can compromise welfare. Long photoperiods combined with low light intensity can result in blindness from buphthalmia (distortions of the eye morphology) or retinal detachment.

Feather pecking occurs frequently amongst commercially reared turkeys and can begin at 1 day of age. This behaviour is considered to be re-directed foraging behaviour, caused by providing poultry with an impoverished foraging environment. To reduce feather pecking, turkeys are often beak-trimmed. Ultraviolet-reflective markings appear on young birds at the same time as feather pecking becomes targeted toward these areas, indicating a possible link.[26] Commercially reared turkeys also perform head-pecking, which becomes more frequent as they sexually mature. When this occurs in small enclosures or environments with few opportunities to escape, the outcome is often fatal and rapid. Frequent monitoring is therefore essential, particularly of males approaching maturity. Injuries to the head receive considerable attention from other birds, and head-pecking often occurs after a relatively minor injury has been received during a fight or when a lying bird has been trodden upon and scratched by another. Individuals being re-introduced after separation are often immediately attacked again. Fatal head-pecking can occur even in small (10 birds), stable groups. Commercial turkeys are normally reared in single-sex flocks. If a male is inadvertently placed in a female flock, he may be aggressively victimised (hence the term 'henpecked'). Females in male groups will be repeatedly mated, during which it is highly likely she will be injured from being trampled upon.

Breeding and companies

The dominant commercial breed is the Broad-breasted Whites (similar to "White Holland", but a separate breed), which have been selected for size and amount of meat. Mature toms are too large to achieve natural fertilization without injuring the hens, so their semen is collected, and hens are inseminated artificially. Several hens can be inseminated from each collection, so fewer toms are needed. The eggs of some turkey breeds are able to develop without fertilization, in a process called parthenogenesis.[27][28] Breeders' meat is too tough for roasting, and is mostly used to make processed meats.

Waste products

Approximately two to four billion pounds of poultry feathers are produced every year by the poultry industry. Most are ground into a protein source for ruminant animal feed, which are able to digest the protein keratin of which feathers are composed. Researchers at the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) have patented a method of removing the stiff quill from the fibers which make up the feather. As this is a potential supply of natural fibers, research has been conducted at Philadelphia University's School of Engineering and Textiles to determine textile applications for feather fibers. Turkey feather fibers have been blended with nylon and spun into yarn, and then used for knitting. The yarns were tested for strength while the fabrics were evaluated as insulation materials. In the case of the yarns, as the percentage of turkey feather fibers increased, the strength decreased. In fabric form, as the percentage of turkey feather fibers increased, the heat retention capability of the fabric increased.

Turkeys as food

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |

|---|---|

| Energy | 465 kJ (111 kcal) |

|

0 g | |

| Sugars | 0 g |

| Dietary fiber | 0 g |

|

0.7 g | |

|

24.6 g | |

| Vitamins | |

| Thiamine (B1) |

(0%) 0 mg |

| Riboflavin (B2) |

(8%) 0.1 mg |

| Niacin (B3) |

(44%) 6.6 mg |

| Pantothenic acid (B5) |

(14%) 0.7 mg |

| Vitamin B6 |

(46%) 0.6 mg |

| Folate (B9) |

(2%) 8 μg |

| Vitamin C |

(0%) 0 mg |

| Minerals | |

| Calcium |

(1%) 10 mg |

| Iron |

(9%) 1.2 mg |

| Magnesium |

(8%) 28 mg |

| Phosphorus |

(29%) 206 mg |

| Potassium |

(6%) 293 mg |

| Sodium |

(3%) 49 mg |

| Zinc |

(13%) 1.2 mg |

| |

|

Percentages are roughly approximated using US recommendations for adults. Source: USDA Nutrient Database [29] | |

Turkeys are traditionally eaten as the main course of Christmas feasts in much of the world (stuffed turkey) since appearing in England in the 16th century,[30] as well as for Thanksgiving in the United States and Canada. While eating turkey was once mainly restricted to special occasions such as these, turkey is now eaten year-round and forms a regular part of many diets.

Turkeys are sold sliced and ground, as well as "whole" in a manner similar to chicken with the head, feet, and feathers removed. Frozen whole turkeys remain popular. Sliced turkey is frequently used as a sandwich meat or served as cold cuts; in some cases, where recipes call for chicken, turkey can be used as a substitute. Additionally, ground turkey is frequently marketed as a healthy ground beef substitute. Without careful preparation, cooked turkey may end up less moist than other poultry meats, such as chicken or duck.

Wild turkeys, while technically the same species as domesticated turkeys, have a very different taste from farm-raised turkeys. In contrast to domesticated turkeys, almost all wild turkey meat is "dark" (even the breast) and more intensly flavored. The flavor can also vary seasonally with changes in available forage, often leaving wild turkey meat with a gamier flavor in late summer due to the greater number of insects in its diet over the preceding months. Wild turkey that has fed predominantly on grass and grain has a milder flavor. Older heritage breeds also differ in flavor.

Unlike chicken, duck, and quail eggs, turkey eggs are not commonly sold as food due to the high demand for whole turkeys and the lower output of turkey eggs as compared with other fowl. The value of a single turkey egg is estimated to be about US $3.50 on the open market, substantially more than a single carton of one dozen chicken eggs.[31][32]

Cooking

| Wikibooks Cookbook has a recipe/module on |

Both fresh and frozen turkeys are used for cooking; as with most foods, fresh turkeys are generally preferred, although they cost more. Around holiday seasons, high demand for fresh turkeys often makes them difficult to purchase without ordering in advance. For the frozen variety, the large size of the turkeys typically used for consumption makes defrosting them a major endeavor: a typically sized turkey will take several days to properly defrost.

Turkeys are usually baked or roasted in an oven for several hours, often while the cook prepares the remainder of the meal. Sometimes, a turkey is brined before roasting to enhance flavor and moisture content. This is necessary because the dark meat requires a higher temperature to denature all of the myoglobin pigment than the white meat (which is very low in myoglobin), so that fully cooking the dark meat tends to dry out the breast. Brining makes it possible to fully cook the dark meat without drying the breast meat. Turkeys are sometimes decorated with turkey frills prior to serving.

In some areas, particularly the American South, turkeys may also be deep fried in hot oil (often peanut oil) for 30 to 45 minutes by using a turkey fryer. Deep frying turkey has become something of a fad, with hazardous consequences for those unprepared to safely handle the large quantities of hot oil required.[33]

Nutritional value

White turkey meat is often considered healthier than dark meat because of its lower fat content, but the nutritional differences are small. Although turkey is reputed to cause sleepiness, holiday dinners are commonly large meals served with carbohydrates, fats, and alcohol in a relaxed atmosphere, all of which are bigger contributors to post-meal sleepiness than the tryptophan in turkey.[34][35]

Turkey litter for fuel

Although most commonly used as fertilizer, turkey litter (droppings mixed with bedding material, usually wood chips) is used as a fuel source in electric power plants. One such plant in western Minnesota provides 55 megawatts of power using 500,000 tons of litter per year. The plant began operating in 2007.[36]

See also

- American Poultry Association

- List of names for the turkey

- List of turkey meat producing companies in the United States

- National Turkey Federation

- Ocellated turkey

- Turkey bowling

Footnotes

- ↑ "UF researchers discover earliest use of Mexican turkeys by ancient Maya". EurekAlert!. August 8, 2012.

- ↑ Speller, C.F., Kemp, B.M., Wyatt, S.D., Monroe, C., Lipe, W.D., Arndt, U.M. and Yang, D. Y. (2010). "Ancient mitochondrial DNA analysis reveals complexity of indigenous North American turkey domestication". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 107 (7): 2807–2812.

- ↑ Webster's II New College Dictionary. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt 2005, ISBN 978-0-618-39601-6, p. 1217

- ↑ C. Michael Hogan. 2008. Wild turkey: Meleagris gallopavo, GlobalTwitcher.com, ed. N. Stromberg

- ↑ "Ancient North & Central American History of the Wild Turkey". Wildturkeyzone.com. Retrieved December 21, 2007.

- 1 2 Emett, Charlie (2003) Walking the Wolds Cicerone Press Limited, 1993 ISBN 1-85284-136-2

- ↑ M. F. Fuller (2004) The encyclopedia of farm animal nutrition ISBN 0-85199-369-9

- ↑ Peach, Howard (2001) Curious Tales of Old East Yorkshire, p. 53. Sigma Leisure.

- ↑ John Harland The house and farm accounts of the Shuttleworths of Gawthorpe Hall in the county of Lancaster at Smithils and Gawthorpe: from September 1582 to October 1621 Chetham society, 1858

- ↑ James G. Dickson, National Wild Turkey Federation (U.S.), United States. Forest Service The Wild turkey: biology and management Stackpole Books, 1992 ISBN 0-8117-1859-X

- ↑ A Victorian Christmas Historic UK.com Retrieved December 26, 2010

- ↑ Charles Dickens (1843) A Christmas carol in prose, being a ghost story of Christmas p.156. Bradbury & Evans

- ↑ "The Turkey Club UK". March 19, 2007. Retrieved December 21, 2007.

- ↑ Dalloul, Rami A.; Long, Julie A.; Zimin, Aleksey V. (September 7, 2010), "Multi-Platform Next-Generation Sequencing of the Domestic Turkey (Meleagris gallopavo): Genome Assembly and Analysis", PLOS Biology, doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1000475

- ↑ Tanya Lewis (November 25, 2015). "How big turkeys were then and now - Business Insider". Business Insider.

- ↑ "Turkey Facts".

- ↑ "Encyclopedia of Life".

- 1 2 Sherwin, C.M., (2010). Turkeys: Behavior, Management and Well-Being. In "The Encyclopaedia of Animal Science". Wilson G. Pond and Alan W. Bell (Eds). Marcel Dekker. pp. 847-849

- ↑ Nixey C (1994). "Lighting for the production and welfare of turkeys". World's Poultry Science Journal. 50: 292–294.

- ↑ Wild Turkey National Geographic.

- ↑ Sandilands, V.; Hocking, P.M., eds. (2012). Alternative Systems for Poultry: Health, Welfare and Productivity (Vol. 30). Cabi.

- ↑ Martrenchar, A., Huonnic, D., Cotte, J. P., Boilletot, E. and Morisse, J.P. (1999). "Influence of stocking density on behavioural, health and productivity traits of turkeys in large flocks". British Poultry Science. 40 (3): 323–331. doi:10.1080/00071669987403.

- ↑ Glatz, P.C. (2013). "Turkey farming - a brief review of welfare and husbandry issues" (PDF). 24th Annual Australian Poultry Science Symposium: 214–217.

- ↑ Marchewka, J., Watanabe, T.T.N., Ferrante, V. and Estevez, I. (2013). "Review of the social and environmental factors affecting the behavior and welfare of turkeys (Meleagris gallopavo)". Poultry Science. 92 (6): 1467–1473. doi:10.3382/ps.2012-02943.

- ↑ Jankowski, J., Mikulski, D., Tatara, M.R. and Krupski, W. (2014). "Effects of increased stocking density and heat stress on growth, performance, carcase characteristics and skeletal properties in turkeys" (PDF). Veterinary Record. doi:10.1136/vr.10221.

- ↑ Sherwin C.M., Devereux C.L. (1999). "A preliminary investigation of ultraviolet-visible markings on domestic turkey chicks and a possible role in injurious pecking". British Poultry Science. 40: 429–433. doi:10.1080/00071669987151.

- ↑ "Discovered in Turkey Eggs: Parthenogenesis", World's Poultry Science Journal (1953), 9: 276-278 Cambridge University Press

- ↑ McDaniel, C D, "Parthenogenesis: Embryonic development in unfertilized eggs may impact normal fertilization and embryonic mortality", MSU Poultry Dept. Spring Newsletter, 1:1. (reproduced on The Poultry Site)

- ↑ "Turkey, fryer-roasters, breast, meat only, raw". USDA Nutrient Database.

- ↑ Davis, Karen (2001) More than a meal: the turkey in history, myth, ritual, and reality Lantern Books, 2001

- ↑ Cecil Adams. "Why can't you buy turkey eggs in stores?". The Straight Dope. Retrieved November 25, 2010.

- ↑ Kasey-Dee Gardner (November 18, 2008). "Why? Tell Me Why!: Turkey Eggs". DiscoveryNews. Retrieved November 25, 2010.

- ↑ "Product Safety Tips: Turkey Fryers". Underwriters Laboratories. Retrieved December 21, 2007.

- ↑ "Does eating turkey make you sleepy?". About.com. Retrieved May 11, 2005.

- ↑ "Researcher talks turkey on Thanksgiving dinner droop". Massachusetts Institute of Technology News Office. Retrieved November 21, 2006.

- ↑ "Turkey-Manure Power Plant Raises Stink with Environmentalists". International Herald Tribune iht.com. Retrieved November 15, 2007.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Turkeys. |

- B.C. researchers carve into today's turkeys through DNA tracking

- Breeds of turkey from Feathersite.com

- More information on turkeys from Cornell

- Study traces roots of turkey taming from Simon Fraser University, Canada.

- Thanksgiving Song