Two-photon absorption

Two-photon absorption (TPA) is the simultaneous absorption of two photons of identical or different frequencies in order to excite a molecule from one state (usually the ground state) to a higher energy electronic state. The energy difference between the involved lower and upper states of the molecule is equal to the sum of the energies of the two photons. Two-photon absorption is a third-order process several orders of magnitude weaker than linear absorption at low light intensities. It differs from linear absorption in that the atomic transition rate due to TPA depends on the square of the light intensity, thus it is a nonlinear optical process, and can dominate over linear absorption at high intensities.[1]

Background

The phenomenon was originally predicted by Maria Goeppert-Mayer in 1931 in her doctoral dissertation.[2] Thirty years later, the invention of the laser permitted the first experimental verification of the TPA when two-photon-excited fluorescence was detected in a europium-doped crystal[3][4]

TPA is a nonlinear optical process. In particular, the imaginary part of the third-order nonlinear susceptibility is related to the extent of TPA in a given molecule. The selection rules for TPA are therefore different from one-photon absorption (OPA), which is dependent on the first-order susceptibility. For example, in a centrosymmetric molecule, one- and two-photon allowed transitions are mutually exclusive. In quantum mechanical terms, this difference results from the need to conserve angular momentum. Since photons have spin of ±1, one-photon absorption requires excitation to involve an electron changing its molecular orbital to one with an angular momentum different by ±1. Two-photon absorption requires a change of +2, 0, or −2.

The third order can be rationalized by considering that a second order process creates a polarization with the doubled frequency. In the third order, by difference frequency generation the original frequency can be generated again. Depending on the phase between the generated polarization and the original electric field this leads to the Kerr effect or to the two-photon absorption. In second harmonic generation this difference in frequency generation is a separated process in a cascade, so that the energy of the fundamental frequency can also be absorbed. In harmonic generation, multiple photons interact simultaneously with a molecule with no absorption events. Because n-photon harmonic generation is essentially a scattering process, the emitted wavelength is exactly 1/n times the incoming fundamental wavelength.[5] This may be better called three photon absorption. In the next paragraph resonant two photon absorption via separate one-photon transitions is mentioned, where the absorption alone is a first order process and any fluorescence from the final state of the second transition will be of second order; this means it will rise as the square of the incoming intensity. The virtual state argument is quite orthogonal to the anharmonic oscillator argument. It states for example that in a semiconductor, absorption at high energies is impossible if two photons cannot bridge the band gap. So, many materials can be used for the Kerr effect that do not show any absorption and thus have a high damage threshold.

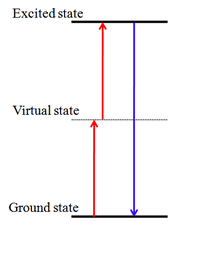

Two-photon absorption can be measured by several techniques. Two of them are two-photon excited fluorescence (TPEF) and nonlinear transmission (NLT). Pulsed lasers are most often used because TPA is a third-order nonlinear optical process,[6] and therefore is most efficient at very high intensities. Phenomenologically, this can be thought of as the third term in a conventional anharmonic oscillator model for depicting vibrational behavior of molecules. Another view is to think of light as photons. In nonresonant TPA two photons combine to bridge an energy gap larger than the energies of each photon individually. If there were an intermediate state in the gap, this could happen via two separate one-photon transitions in a process described as "resonant TPA", "sequential TPA", or "1+1 absorption". In nonresonant TPA the transition occurs without the presence of the intermediate state. This can be viewed as being due to a "virtual" state created by the interaction of the photons with the molecule.

The "nonlinear" in the description of this process means that the strength of the interaction increases faster than linearly with the electric field of the light. In fact, under ideal conditions the rate of TPA is proportional to the square of the field intensity. This dependence can be derived quantum mechanically, but is intuitively obvious when one considers that it requires two photons to coincide in time and space. This requirement for high light intensity means that lasers are required to study TPA phenomena. Further, in order to understand the TPA spectrum, monochromatic light is also desired in order to measure the TPA cross section at different wavelengths. Hence, tunable pulsed lasers (such as frequency-doubled Nd:YAG-pumped OPOs and OPAs) are the choice of excitation.

Measurements

Absorption rate

The Beer's law for one photon absorption:

changes to

for TPA with light intensity as a function of path length or cross section x as a function of concentration c and the initial light intensity I0. The absorption coefficient α now becomes the TPA coefficient β. (Note that there is some confusion over the term β in nonlinear optics, since it is sometimes used to describe the second-order polarizability, and occasionally for the molecular two-photon cross-section. More often however, it is used to describe the bulk 2-photon optical density of a sample. The letter δ or σ is more often used to denote the molecular two-photon cross-section.)

Units of cross-section

The molecular two-photon cross-section is usually quoted in the units of Goeppert-Mayer (GM) (after its discoverer, Nobel laureate Maria Goeppert-Mayer), where 1 GM is 10−50 cm4 s photon−1.[7] Considering the reason for these units, one can see that it results from the product of two areas (one for each photon, each in cm2) and a time (within which the two photons must arrive to be able to act together). The large scaling factor is introduced in order that 2-photon absorption cross-sections of common dyes will have convenient values.

Development of the field and potential applications

Until the early 1980s, TPA was used as a spectroscopic tool. Scientists compared the OPA and TPA spectra of different organic molecules and obtained several fundamental structure property relationships. However, in late 1980s, applications started to be developed. Peter Rentzepis suggested applications in 3D optical data storage. Watt Webb suggested microscopy and imaging. Other applications such as 3D microfabrication, optical logic, autocorrelation, pulse reshaping and optical power limiting were also demonstrated [8]

Microfabrication and lithography

One of the most distinguishing features of TPA is that the rate of absorption of light by a molecule depends on the square of the light's intensity. This is different from OPA, where the rate of absorption is linear with respect to input intensity. As a result of this dependence, if material is cut with a high power laser beam, the rate of material removal decreases very sharply from the center of the beam to its periphery. Because of this, the "pit" created is sharper and better resolved than if the same size pit were created using normal absorption.

3D photopolymerization

In 3D microfabrication, a block of gel containing monomers and a 2-photon active photoinitiator is prepared as a raw material. Application of a focused laser to the block results in polymerization only at the focal spot of the laser, where the intensity of the absorbed light is highest. The shape of an object can therefore be traced out by the laser, and then the excess gel can be washed away to leave the traced solid.

Imaging

The human body is not transparent to visible wavelengths. Hence, one photon imaging using fluorescent dyes is not very efficient. If the same dye had good two-photon absorption, then the corresponding excitation would occur at approximately two times the wavelength at which one-photon excitation would have occurred. As a result, it is possible to use excitation in the far infrared region where the human body shows good transparency. It is sometimes said, incorrectly, that Rayleigh scattering is relevant to imaging techniques such as two-photon. According to Rayleigh's scattering law, the amount of scattering is proportional to , where is the wavelength. As a result, if the wavelength is increased by a factor of 2, the Rayleigh scattering is reduced by a factor of 16. However, Rayleigh scattering only takes place when scattering particles are much smaller than the wavelength of light (the sky is blue because air molecules scatter blue light much more than red light). When particles are larger, scattering increases approximately linearly with wavelength: hence clouds are white since they contain water droplets. This form of scatter is known as Mie scattering and is what occurs in biological tissues. So, although longer wavelengths do scatter less in biological tissues, the difference is not as dramatic as Rayleigh's law would predict.

Optical power limiting

Another area of research is optical power limiting. In a material with a strong nonlinear effect, the absorption of light increases with intensity such that beyond a certain input intensity the output intensity approaches a constant value. Such a material can be used to limit the amount of optical power entering a system. This can be used to protect expensive or sensitive equipment such as sensors, can be used in protective goggles, or can be used to control noise in laser beams.

Photodynamic therapy

Photodynamic therapy (PDT) is a method for treating cancer. In this technique, an organic molecule with a good triplet quantum yield is excited so that the triplet state of this molecule interacts with oxygen. The ground state of oxygen has triplet character. This leads to triplet-triplet annihilation, which gives rise to singlet oxygen, which in turn attacks cancerous cells. However, using TPA materials, the window for excitation can be extended into the infrared region, thereby making the process more viable to be used on the human body.

Optical data storage

The ability of two-photon excitation to address molecules deep within a sample without affecting other areas makes it possible to store and retrieve information in the volume of a substance rather than only on a surface as is done on the DVD. Therefore, 3D optical data storage has the possibility to provide media that contain terabyte-level data capacities on a single disc.

TPA compounds

To some extent, linear and 2-photon absorption strengths are linked. Therefore, the first compounds to be studied (and many that are still studied and used in e.g. 2-photon microscopy) were standard dyes. In particular, laser dyes were used, since these have good photostability characteristics. However, these dyes tend to have 2-photon cross-sections of the order of 0.1-10 GM, much less than is required to allow simple experiments.

It was not until the 1990s that rational design principles for the construction of two-photon-absorbing molecules began to be developed, in response to a need from imaging and data storage technologies, and aided by the rapid increases in computer power that allowed quantum calculations to be made. The accurate quantum mechanical analysis of two-photon absorbance is orders of magnitude more computationally intensive than that of one-photon absorbance, requiring highly correlated calculations at very high levels of theory.

The most important features of strongly TPA molecules were found to be a long conjugation system (analogous to a large antenna) and substitution by strong donor and acceptor groups (which can be thought of as inducing nonlinearity in the system and increasing the potential for charge-transfer). Therefore, many push-pull olefins exhibit high TPA transitions, up to several thousand GM.[9] It is also found that compounds with a real intermediate energy level close to the "virtual" energy level can have large 2-photon cross-sections as a result of resonance enhancement.

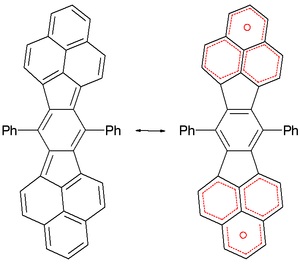

Compounds with interesting TPA properties also include various porphyrin derivatives, conjugated polymers and even dendrimers. In one study [10] a diradical resonance contribution for the compound depicted below was also linked to efficient TPA. The TPA wavelength for this compound is 1425 nanometer with observed TPA cross section of 424 GM.

TPA Coefficients

The two photon absorption coefficient is defined by the relation [11]

so that

Where is the two-photon absorption coefficient, is the absorption coefficient, is the transition rate for TPA per unit volume, is the irradiance, ħ is the Dirac constant, is the photon frequency and the thickness of the slice is . N is the number density of molecules per cm3, E is the photon energy (J), σ(2) is the two-photon absorption cross section (cm4s/molecule).

The SI units of the beta coefficient are m/W. If β (m/W) is multiplied by 10−9 it can be converted to the CGS system (cal/cm s/erg).[12]

Due to different laser pulses the TPA coefficients reported has differed as much as a factor 3. With the transition towards shorter laser pulses, from picosecond to subpicosecond durations, noticeably reduced TPA coefficient have been obtained.[13]

TPA in Water

Laser induced TPA in water was discovered in 1980.[14]

Water absorbs UV radiation near 125 nm exiting the 3a1 orbital leading to dissociation into OH⁻ and H⁺. Through TPA this dissociation can be achieved by two photons near 266 nm.[15] Since water and heavy water have different vibration frequencies and inertia they also need different photon energies to achieve dissociation and have different absorption coefficients for a given photon wavelength. A study from Jan 2002 used a femtosecond laser tuned to 0.22 Picoseconds found the coefficient of D2O to be 42±5 10−11(cm/W) whereas H2O was 49±5 10−11(cm/W) [13]

| λ (nm) | pulse duration τ (ps) | (cm/W) |

|---|---|---|

| 315 | 29 | 4 |

| 300 | 29 | 4.5 |

| 289 | 29 | 6 |

| 282 | 29 | 7 |

| 282 | 0.18 | 19 |

| 266 | 29 | 10 |

| 264 | 0.22 | 49±5 |

| 216 | 15 | 20 |

| 213 | 26 | 32 |

Two-photon emission

The opposite process of TPA is two-photon emission (TPE), which is a single electron transition accompanied by the emission of a photon pair. The energy of each individual photon of the pair is not determined, while the pair as a whole conserves the transition energy. The spectrum of TPE is therefore very broad and continuous.[16] TPE is important for applications in astrophysics, contributing to the continuum radiation from planetary nebulae (theoretically predicted for them in [17] and observed in [18]). TPE in condensed matter and specifically in semiconductors was only recently observed,[19] with emission rates nearly 5 orders of magnitude weaker than one-photon spontaneous emission, with potential applications in quantum information.

See also

- Virtual particles are in virtual state where the probability amplitude is not conserved.

- Two-photon circular dichroism

- Two-photon excitation microscopy

References

- ↑ Tkachenko, Nikolai V. (2006). "Appendix C. Two photon absorption". Optical Spectroscopy: Methods and Instrumentations. Elsevier. p. 293. ISBN 978-0-08-046172-4.

- ↑ Goeppert-Mayer M (1931). "Über Elementarakte mit zwei Quantensprüngen". Annals of Physics. 9 (3): 273–95. Bibcode:1931AnP...401..273G. doi:10.1002/andp.19314010303.

- ↑ Kaiser, W.; Garrett, C. G. B. (1961). "Two-Photon Excitation in CaF2:Eu2+". Physical Review Letters. 7 (6): 229. Bibcode:1961PhRvL...7..229K. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.7.229.

- ↑ Abella, I.D. (1962). "Optical double-quantum absorption in cesium vapor". Physical Review Letters. 9 (11): 453. Bibcode:1962PhRvL...9..453A. doi:10.1103/physrevlett.9.453.

- ↑ "SVI | SecondHarmonicGeneration". Svi.nl. Retrieved 2015-03-12.

- ↑ Mahr, H. (2012). "Chapter 4. Two-Photon Absorption Spectroscopy". In Herbert Rabin, C. L. Tang. Quantum Electronics: A Treatise, Volume 1. Nonlinear Optics, Part A. Academic Press. pp. 286–363. ISBN 978-0-323-14818-4.

- ↑ Powerpoint presentation http://www.chem.ucsb.edu/~ocf/lecture_ford.ppt

- ↑ Hayat, Alex; Nevet, Amir; Ginzburg, Pavel; Orenstein, Meir (2011). "Applications of two-photon processes in semiconductor photonic devices: Invited review". Semiconductor Science and Technology. 26 (8): 083001. Bibcode:2011SeScT..26h3001H. doi:10.1088/0268-1242/26/8/083001.

- ↑ Kogej, T.; Beljonne, D.; Meyers, F.; Perry, J.W.; Marder, S.R.; Brédas, J.L. (1998). "Mechanisms for enhancement of two-photon absorption in donor–acceptor conjugated chromophores". Chemical Physics Letters. 298: 1–6. Bibcode:1998CPL...298....1K. doi:10.1016/S0009-2614(98)01196-8.

- ↑ Kamada, Kenji; Ohta, Koji; Kubo, Takashi; Shimizu, Akihiro; Morita, Yasushi; Nakasuji, Kazuhiro; Kishi, Ryohei; Ohta, Suguru; Furukawa, Shin-Ichi; Takahashi, Hideaki; Nakano, Masayoshi (2007). "Strong Two-Photon Absorption of Singlet Diradical Hydrocarbons". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 46 (19): 3544–3546. doi:10.1002/anie.200605061.

- ↑ Bass, Michael (1994). HANDBOOK OF OPTICS Volume I. McGraw-Hill Professional; 2 edition (September 1, 1994). 9 .32. ISBN 0-07-047740-X.

- ↑ Marvin, Weber (2003). Handbook of optical materials. Laser and Optical Science and Technology Series. The CRC Press. APPENDIX V. ISBN 978-0-8493-3512-9.

- 1 2 3 Dragonmir, Adrian; McInerney, John G.; Nikogosyan, David N. (2002). "Femtosecond Measurements of Two-Photon Absorption Coefficients at λ = 264 nm in Glasses, Crystals, and Liquids". Applied Optics. 41 (21): 4365–4376. Bibcode:2002ApOpt..41.4365D. doi:10.1364/AO.41.004365. PMID 12148767.

- ↑ Nikogosyan, D. N.; Angelov, D. A. (1981). "Formation of free radicals in water under high-power laser UV irradiation,". Chemical Physics Letters. 77: 208–210. Bibcode:1981CPL....77..208N. doi:10.1016/0009-2614(81)85629-1.

- ↑ Underwood, J.; Wittig, C. (2004). "Two photon photodissociation of H2O via the B state". Chemical Physics Letters. 386: 190–195. Bibcode:2004CPL...386..190U. doi:10.1016/j.cplett.2004.01.030.

- ↑ Chluba, J.; Sunyaev, R. A. (2006). "Induced two-photon decay of the 2s level and the rate of cosmological hydrogen recombination". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 446: 39. arXiv:astro-ph/0508144

. Bibcode:2006A&A...446...39C. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20053988.

. Bibcode:2006A&A...446...39C. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20053988. - ↑ Spitzer, L.; Greenstein, J. (1951). "Continuous emission from planetary nebulae". Astrophysical Journal. 114: 407. Bibcode:1951ApJ...114..407S. doi:10.1086/145480.

- ↑ Gurzadyan, G. A. (1976). "Two-photon emission in planetary nebula IC 2149". Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific. 88 (526): 891–895. doi:10.1086/130041. JSTOR 40676041.

- ↑ Hayat, A.; Ginzburg, P.; Orenstein, M. (2008). "Observation of Two-Photon Emission from Semiconductors". Nature Photon. 2 (4): 238. doi:10.1038/nphoton.2008.28.