United Kingdom of the Netherlands

| Kingdom of the Netherlands | ||||||||||||||||||

| Koninkrijk der Nederlanden (Dutch) Royaume des Belgiques (French) | ||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||

| Motto "Je maintiendrai" (French) "I will uphold" | ||||||||||||||||||

| Anthem "Those in whom Dutch blood" | ||||||||||||||||||

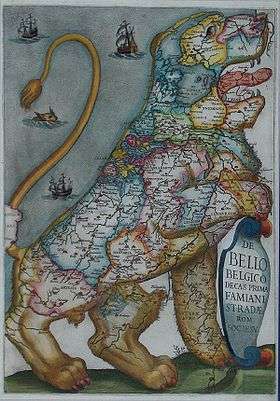

Map of the United Kingdom of the Netherlands in 1815. The Grand Duchy of Luxembourg is shown in light green. | ||||||||||||||||||

| Capital | Amsterdam and Brussels | |||||||||||||||||

| Languages | Dutch (official, all over the kingdom), French (official, in the Walloon provinces and in the Parliament), Frisian, Luxembourgish. | |||||||||||||||||

| Religion | Protestant, Catholic | |||||||||||||||||

| Government | Constitutional monarchy | |||||||||||||||||

| King | ||||||||||||||||||

| • | 1815–1839 | William I | ||||||||||||||||

| Legislature | States General | |||||||||||||||||

| • | Upper house | Senate | ||||||||||||||||

| • | Lower house | House of Representatives | ||||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Early modern period | |||||||||||||||||

| • | Congress of Vienna | 16 March 1815 | ||||||||||||||||

| • | Constitution adopted | 24 August 1815 | ||||||||||||||||

| • | Belgian Revolution | 25 August 1830 | ||||||||||||||||

| • | Treaty of London | 19 April 1839 | ||||||||||||||||

| Currency | Dutch guilder | |||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||

United Kingdom of the Netherlands (1815–1839) (Dutch: Verenigd Koninkrijk der Nederlanden, French: Royaume uni des Pays-Bas) was the unofficial name for the Kingdom of the Netherlands (Dutch: Koninkrijk der Nederlanden, French: Royaume des Belgiques[1]) during the period after it was first created from part of the First French Empire and before the new Kingdom of Belgium split off from it in 1830.

This state, a large part of which still exists today as the Kingdom of the Netherlands, was made up of the former Dutch Republic (Republic of the Seven United Netherlands) to the north, the former Austrian Netherlands to the south, and the former Prince-Bishopric of Liège. The House of Orange-Nassau came to be the monarchs of this new state.

The United Kingdom of the Netherlands collapsed after the 1830 Belgian Revolution. William I, King of the Netherlands, would refuse to recognize a Belgian state until 1839, when he had to yield under pressure by the Treaty of London. Only at this time were exact borders agreed upon.[2]

Nowadays, the Benelux Union (created in 1944 between Netherlands, Belgium and Luxembourg) is in some ways a "distant heir" of the former United Kingdom of the Netherlands. Their respective political systems are very similar and Dutch is the official and vernacular language of 83% of its total population.

Background

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of the Netherlands |

|

|

|

After the liberation of the Netherlands in 1813 by Prussian and Russian troops, it was taken for granted that any new regime would have to be headed by William Frederik of Orange-Nassau, the son of the last stadtholder William V of Orange-Nassau and Princess Wilhelmina of Prussia. William returned to The Hague, where on 6 December he was offered the title of King. He refused, instead proclaiming himself "Sovereign Prince" of the Principality of the United Netherlands.

Unification under William I

During the Congress of Vienna in 1815 France had to give up its rule of the Southern Netherlands. These negotiations were not easy, because William tried to get as much out of it as he could. His ideas of a United Netherlands were based upon the actions of Hendrik van der Noot, a lawyer and politician and one of the main players in the Revolution of the Southern Netherlands against the Austrian Emperor (1789–1790). In 1789, after the Southern Netherlands declared themselves independent, Hendrik knew this was a fragile state and he tried to be reunited with the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands. Since then William had never forgotten this and after the fall of Napoleon he saw a chance.

Three different scenarios were made:

- The Northern Netherlands restored within its old borders and the Southern Netherlands would become a barrier state under the rule of a great power, like Austria.

- If the Southern Netherlands would stay (partially) French, the Northern Netherlands should be extended to the Nete River or probably the whole of Flanders. In this scenario also portions of Germany would become Dutch. Then the border would be the line Mechelen-Maastricht-Jülich-Cologne-Düsseldorf where it ends at the river Rhine.

- France within its old borders, the Northern Netherlands unified with the Southern Netherlands and all of German territories on the left bank of the Rhine and north of the Moselle and the old Duchy of Berg and the old Lands of Nassau on the right bank of the Rhine.

The first two scenarios came from "Memorandum of Holland" made in 1813 after the Battle of Leipzig. The last scenario came from William himself. The first scenario never made it because the Great Powers (Great Britain, Prussia, Austria and Russia) thought an independent Southern Netherlands/Belgium under an Austrian Prince was too weak and Austria was not interested in getting it back.

The Dutch question became a problem. The Great Powers of Europe chose the last scenario, but didn't want to go as far in enlarging the Netherlands as William had wanted.

In the end, the Eight Articles of London granted William sovereignty over the following lands:

- The Republic of the Seven United Netherlands (i.e., the Principality of the United Netherlands)

- The Austrian Netherlands within its borders of 1789 (so without French Flanders)

- The Prince-Bishopric of Liège, but on Prussia's behalf small changes were made to its borders

William was named Governor-General of the Austrian Netherlands including Liège, which he temporarily ruled for Prussia. It was later incorporated into the Kingdom of the Netherlands. The Duchy of Luxembourg was not fully granted to William, because it was a member of the German Confederation. William however demanded that Luxembourg become a part of the Netherlands, as a unified Netherlands was stronger as a buffer for France. Historically it had been a part of the Seventeen Provinces or Burgundian Netherlands up to 1648, but Luxembourg was still a part of the discussions.

On 1 March 1815, while the Congress of Vienna was still going on, Napoleon escaped from Elba and he created a large army against the Great Powers of Europe. He was defeated at the Battle of Waterloo (at that time within the kingdom) by Prussian, British, Belgian, Dutch and Nassau (under the prince of Orange) troops.

In response, on 16 March 1815, William proclaimed the Netherlands a kingdom, with himself as King William I.

Furthermore, on 31 May 1815, William concluded a treaty at the Congress of Vienna whereby he ceded the Principality of Orange-Nassau to the Kingdom of Prussia in exchange for the Duchy of Luxembourg. As part of the deal, the Duchy was elevated to a Grand Duchy in a personal and (until 1839) political union with the Netherlands - albeit remaining within the German Confederation, being garrisoned by Prussian troops on behalf of the Dutch king.

With the unification, William completed his family's three-century quest (started by his ancestor William the Silent in 1579) to unite the Low Countries under a single rule.

Terminology

"Royaume uni des Pays-Bas" never was the French official name of this short-lived kingdom. This French unofficial name stayed in the common language to avoid any confusion with the rest of the Netherlands after the Belgian Revolution and secession (1830-1839). Both in international treaties and national legislation was the country indifferently referred in French to "Royaume des Belgiques" ("Belgiques" in the plural) and "Royaume des Pays-Bas".

From the 17th century until the revolution of 1830 were the English "Netherlands", Dutch "Nederlanden", Latin "Belgium" (or "Belgica") and French "Pays-Bas" or "Belgique" (in the singular) more or less interchangeable. For example, the Dutch colony of New Netherlands (North America) was called in Latin "Nova Belgica" or "Novum Belgium", in Dutch "Nieuw-Nederland" and in French... "Nouvelle-Hollande". Likewise, the United States of Belgium (the first independent and short-lived Belgian state, 1789-1790) were called in French "États belgiques unis", in Dutch "Verenigde Nederlandse Staten" and in Latin "Status Belgii Fœderati" or "Belgium Fœderatum".

At the start of the Orange regime, harsh discussions arose - especially in the Southern provinces - about the way to "qualify" the inhabitants of the new kingdom and the latter itself. In common language (in Flemish as in French), it wasn't a problem to talk about "de Nederlanden" or "les Pays-Bas". For the Flemings, it was uneasy but not totally irrelevant to be referred to "Nederlanders" (adj. "Nederlands"), even if they now preferred to be called "Belgen" (adj. "Belgisch"). Contrariwise was it absolutely irrelevant for the Frenchspeaking elites to be called "Néerlandais" (King William furthermore wanted to create the French neologism "Néerlande"...) and they demanded to be named "Belges". So, confronted to a wide protest in the elite circles from the South, the regime decided to translate the Dutch "Nederlanden", "Het Nederlandse volk", "Nederlanders" and "Nederlands" by the French "Belgiques", "Le peuple belge", "Belges" and "belge". Moreover, in French, it wasn't referred to a "langue néerlandaise" but to a "langue belgique".[3][4]

But even the latter decision also caused turmoil in the South: some Walloons and Flemings (French speakers as Flemish speakers) petitioned vehemently, arguing they didn't want to share "their" name with the "Hollanders". To illustrate the complexity of this "terminological mess", one among the most radical and republican opposition newspapers published in the South was named Le Courrier des Pays-Bas.[5]

After the Belgian secession, the Southern provinces choose as an official name "Kingdom of Belgium". In French, the new state was called "Royaume de Belgique" ("Belgique" in the singular), while it was necessary to find a neologism for the Dutch official name to be used by the Flemings: "Koninkrijk België". Finally, to establish a clear distinction with the Northern provinces, the official Latin name became "Regnum Belgicæ" or "Belgica" (and no more "Regnum Belgii" or "Belgium", both reserved to the North until the eve of de 20th century). Since then, the Latin (mostly honorific) names for the North are "Nederlandia" and sometimes "Batavia".

Power of the King

The newly formed kingdom was not like the Netherlands or Belgium today. Under the constitution, King William was both head of state and head of government, and had considerably more power than a King or Queen in a modern constitutional monarchy.

The Second Chamber of the States General of the Netherlands had 110 members. Despite the south's far greater population, both halves of the kingdom each elected 55 members—a source of considerable resentment in the south. The First Chamber was appointed by the king and consisted of old and new noblemen.

The Netherlands had eight ministers, who were responsible only to the King himself. In fact, they followed his demands. The King also could rule by "Royal Order".

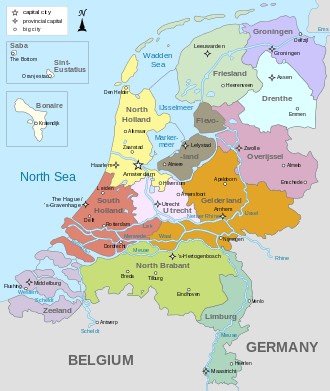

Provinces

The Kingdom consisted of 17 provinces[6] (BE means currently part of Belgium, NL means currently part of the Netherlands; the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg, although not a Province, was constitutionally tied to the Kingdom).

In the North, the provinces kept the former administrative boundaries of the French departments, themselves shaped according to the former seven United Provinces of the Netherlands.

In the South, the provinces were grosso modo shaped according to the former French departments but - in a "Restoration" spirit - they were renamed to refer to the former principalities of the pre-revolutionary Southern Netherlands and Prince-Bishopric of Liège.

- Antwerp (BE): former Deux-Nèthes department

- Drenthe (NL)

- East Flanders (BE): former Escaut department (without Zeelandic Flanders)

- Friesland (NL)

- Gelderland (NL)

- Groningen (NL)

- Hainaut (BE): former Jemmape department

- Holland (NL)

- Limburg (NL/BE): Limburg, NL and Limburg, BE: former Meuse-Inférieure department

- Liège (BE): former Ourthe department

- Namur (BE): former Sambre-et-Meuse department

- North Brabant (NL)

- Overijssel (NL)

- South Brabant, renamed to Brabant in 1831 (BE): former Dyle department

- Utrecht (NL)

- West Flanders (BE): former Lys department

- Zeeland (NL)

Economic and social development

Economically the new state prospered, although many people in the north were unemployed and lived in poverty because a lot of British goods had destabilised the Dutch trade market.

Although financially stable, the south also had the burden of the nation's debt, but gained new trade markets in the Dutch colonies. Many people's welfare improved in the south because the profits of trade were used for big projects.

William tried to divide the nation's wealth more equally through, among others, the following actions:

- Constructing new roads

- Digging new canals and widening/deepening existing canals:(North-Holland canal, Canal from Gent to Terneuzen, Brussels-Charleroi Canal, Moselle canal, canal of Liège)

- Extending the steel industry to the south

- Instating the Metric System

- Levying new import and export taxes

- Opening the harbour of Antwerp

Through these actions export of cotton, sheets, weapons and steel products increased. The fleet of Antwerp grew to 117 ships. Many of these projects were funded by King William himself.

The educational system was extended. Under William's rule the number of school-going children doubled from 150,000 to 300,000 by opening 1,500 new public schools. The south especially needed schools because many people could not read or write.

In 1825 William founded the Dutch Trading Company (Dutch: Nederlandse Handels Maatschappij), to boost trade with the colonies.

The way to separation

Social differences

Socially, the unification created many problems. Although William set out from the start to create a single people, it soon became apparent that the north and south had drifted far apart culturally in the 200 years since the south was reconquered by the Habsburgs. In particular, the mentalities of the Burgundian south and Calvinistic north did not tolerate each other very well. Both the north and the south had a different historical background and the Dutch- and French-speaking people both were afraid of being overruled by each other. France played a role in this by the "Légion belge et parisienne", financed with private funds but with permission of the French government, to make a unification with France possible.

The north had built up an independent history, and had experienced a golden age. William and his northern subjects saw the south more as a territorial gain than a partner. Although 62% of the population lived in the South, they were assigned the same number of representatives in the States General as the North. This was exacerbated by the fact that the north had more representation in the Second Chamber, since it was divided into more provinces than the south. Therefore, the more populous Belgians felt significantly under-represented.

A linguistic reform in 1823 intended to make Dutch the official language in the Flemish provinces, because it was the language of most of the Flemish population. This reform met with strong opposition from the Flemish upper and middle classes who at the time were mostly French speaking.

Religious and political differences

Religion was also a reason for separation. The north was dominantly Protestant, whereas the south was Catholic. The Catholic Church saw its influence declining in favour of the king. He built over 1,500 state schools where the Church was no longer the provider of education.

Citations

- ↑ Encyclopædia Universalis, Belgique, Histoire, 8. La parenthèse française et hollandaise (1795-1830) (http://www.universalis.fr/encyclopedie/belgique-histoire/8-la-parenthese-francaise-et-hollandaise-1795-1830/). Encyclopædia Universalis, Pays-Bas, 7. Révolution et restauration 1780-1830 (http://www.universalis.fr/encyclopedie/pays-bas/7-revolution-et-restauration-1780-1830/).

- ↑ Originally, the official title of William I, King of the Netherlands, was: in Dutch: Koning der Nederlanden; in French: Roi des Belgiques (Belgiques in the plural); in Latin:Rex Belgii (in the singular and not in the plural Rex Belgiorum). After the Belgian Revolution, the Belgian monarch has been called King of the Belgians. In Dutch: Koning der Belgen; in French: Roi des Belges (and not Roi de Belgique); In Latin: Rex Belgarum (and not Rex Belgii).

- ↑ Schepper (de), Hugo (2003), Een verhaal over historische identiteit en identiteitsbesef in de Lage Landen. In De Tachtigjarige Oorlog. Universiteit Leiden. "Onder het Koninkrijk der Nederlanden van koning Willem I, dat in het Frans "le Royaume des Belgiques" heette, werden in de officiële stukken de termen het Nederlandsche volk en Nederlanders stelselmatig respectievelijk met la Nation Belge en Belges vertaald. In 1821 verscheen voor Franstaligen een Nederlandse spraakkunst onder de titel "Grammaire de la langue belgique".".

- ↑ Moke, J.J. (1822). Les principes de la langue belgique, mis à la portée de ceux qui savent le français. Gand: Houdin. "Sous le nom de Langue Belgique, j'entends la langue qu'on appelle vulgairement 'Hollandaise', c'est-à-dire: - le dialecte belgique le plus répandu et incomparablement le plus cultivé. [...] Je n'ai point cru devoir apprendre au lecteur les principes de grammaire générale, communs aux deux langues; je me suis simplement borné à lui faire connaître ce que le Belgique offre de 'spécial', dans son orthographe et sa syntaxe."

- ↑ Wils, Lode (2009). Van de Belgische naar de Vlaamse natie: een geschiedenis van de Vlaamse beweging. Leuven: Acco. p. 38: "In het Verenigd Koninkrijk (1815-1830) probeerde de overheid de vroegere equatie opnieuw ingang te doen vinden tussen de termen 'België' en 'Nederland', 'Belgen' en 'Nederlanders', als synoniemen voor het hele rijk en zijn bewoners. Maar aangezien er van 'Pays-Bas' geen [Franse] benaming kon worden afgeleid voor de inwoners, en evenmin een bijvoeglijk [Frans] naamwoord, bracht ze de termen 'Néerlande' en 'Néerlandais' in omloop. Daartegen tekenden sommigen heftig protest aan, die alleen 'Belgen' wilden genoemd worden en deze naam niet met de 'Hollanders' wilden delen."

- ↑ Bohn, François (1816). Nieuwe kaart van het Koningrijk der Nederlanden en het Groot Hertogdom Luxemburg volgens de bepalingen van het Weener Congres, en het Parijsche Vredes Tractaat van 1815. Schaal [ca. 1:1.000.000]. Haarlem: C. van Baarsel en zoon. Universiteit van Amsterdam (2013), Atlas der Neederlanden, Amsterdam: UVA.

References

- Aerts, Juul Frans; Vangenechten, Konstant (1957). Nederlands-Latijns Lexicon (3rd ed.). Turnhout: Brepols. p. 247.

- Bischoff, Friedrich Heinrich; Möller Johann Heinrich (1829). Vergleinchendes Wörterbuch der alten, mittleren und neuen Geographie. Gotha.

- Blom, Hans; Lamberts, Emiel (2003). Geschiedenis van de Nederlanden. Amersfoort: ThiemeMeulenhoff.

- Dictionnaire géographique universel, Le tout tiré du Dictionnaire Géographique Latin de Baudrand (1724). Amsterdam & Utrecht.

- Dubois, Sébastien (2005). L'invention de la Belgique : genèse d'un État-nation 1648-1830. Bruxelles: Racine.

- Ferrari, Filippo; Baudrand, Michel-Antoine (1738). Novum Lexicum geographicum. Venise.

- Grässe, Johann Georg Theodor (1861). Orbis Latinus, Dresden.

- Hubner, Jean (1757). La géographie universelle. Tome 1. Bâle.

- Mauro, Frédéric; Peeters, Guido; Skornicki, Arnault; Vandermotten, Christian (2014). Pays-Bas. Encyclopædia Universalis.

- Moke, J.J. (1822). Les principes de la langue belgique, mis à la portée de ceux qui savent le français. Gand: Houdin.

- Montijn, J.F.L. (1946). Nederlands-Latijns Woordenboek. Zwolle: W.E.J. Tjeenk Willink.

- Peeters, Guido (2014), Belgique - Histoire. Encyclopædia Universalis.

- Robert, François (1818). Dictionnaire géographique, d'après le Recès du Congrès de Vienne, le Traité de Paris, du 20 novembre 1815, et autres actes publics les plus récens. Paris.

- Schepper (de), Hugo (2003), Een verhaal over historische identiteit en identiteitsbesef in de Lage Landen. In De Tachtigjarige Oorlog. Universiteit Leiden.

- Tachard Guido; Jaques, B.; Hannot, Samuel (1699). Dictionarium Latino-Belgicum. Dordrecht & Rotterdam: Theodor Goris & Peter Vander Slaart.

- Van Hees, Pieter; de Schepper, Hugo (1995). Tussen cultuur en politiek: het Algemeen-Nederlands Verbond 1895-1995. Hilversum: Uitgeverij Verloren.

- Wils, Lode (2009). Van de Belgische naar de Vlaamse natie: een geschiedenis van de Vlaamse beweging. Leuven: Acco.

- de Schepper, Hugo (2014). Belgium dat is Nederlandt, Identiteiten en identiteitenbesef in de Lage Landen, 1200 - 1800. Breda: Papieren Tijger.

.svg.png)