American wine

American wine has been produced for over 300 years. Today, wine production is undertaken in all fifty states, with California producing 89 percent of all US wine.[1] The United States is the fourth-largest wine producing country in the world after France, Italy, and Spain.[2]

The North American continent is home to several native species of grape, including Vitis labrusca, Vitis riparia, Vitis rotundifolia, and Vitis vulpina. But the wine making industry is based on the cultivation of the European Vitis vinifera, which was introduced by European settlers.[3] With more than 1,100,000 acres (4,500 km2) under vine, the United States is the sixth-most planted country in the world after France, Italy, Spain, China and Turkey.[4]

History

The first Europeans to explore North America, a Viking expedition from Greenland, called it Vinland because of the profusion of grape vines they found. The earliest wine made in what is now the United States was produced between 1562 and 1564 by French Huguenot settlers from Scuppernong grapes at a settlement near Jacksonville, Florida.[2] In the early American colonies of Virginia and the Carolinas, wine making was an official goal laid out in the founding charters. However, settlers discovered that the wine made from the various native grapes had flavors which were unfamiliar and which they did not like.

This led to repeated efforts to grow the familiar European Vitis vinifera varieties, beginning with the Virginia Company exporting French vinifera vines with French vignerons to Virginia in 1619. These early plantings met with failure as native pest and vine disease ravaged the vineyards. In 1683, William Penn planted a vineyard of French vinifera in Pennsylvania; it may have interbred with a native Vitis labrusca vine to create the hybrid grape Alexander. One of the first commercial wineries in the United States was founded in 1787 by Pierre Legaux in Pennsylvania. A settler in Indiana in 1806 produced wine made from the Alexander grape. Today French-American hybrid grapes are the staples of wine production on the East Coast of the United States.[4]

The Kentucky General Assembly on November 21, 1799 passed a bill to establish a commercial vineyard and winery.[5] The vinedresser for the vineyard was John James Dufour, formerly of Vevey, Switzerland.[4] The vineyard was located overlooking the Kentucky River in Jessamine County in what is known as Blue Grass country of central Kentucky. Dufour named it First Vineyard on November 5, 1798.[6] The vineyard's current address in 5800 Sugar Creek Pike, Nicholasville, Kentucky. The first wine from First Vineyard was consumed by subscribers to the vineyard at John Postelthwaite's house on March 21, 1803.[7] Two 5-gallon oak casks of wine were taken to President Thomas Jefferson in Washington, D.C. in February 1805.[8] The vineyard continued until 1809, when a killing freeze in May destroyed the crop and many vines. The Dufour family abandoned Kentucky and migrated west to Vevay, Indiana, a center of a Swiss-immigrant community.[9]

In California, the first vineyard and winery was established in 1769 by the Franciscan missionary Junípero Serra near San Diego. Later missionaries carried vines northward; Sonoma's first vineyard was planted around 1805.[3] California has two native grape varieties, but they make very poor quality wine. The California Wild Grape (Vitis californicus) does not produce wine-quality fruit, although it sometimes is used as rootstock for wine grape varieties.[10] The missionaries used the Mission grape. (In South America, this grape is known as criolla or "colonialized European".) Although a Vitis vinifera variety, it is a grape of "very modest" quality. Jean-Louis Vignes was one of the early settlers to use a higher quality vinifera in his vineyard near Los Angeles.[3]

The first winery in the United States to become commercially successful was founded in Cincinnati, Ohio in the mid-1830s by Nicholas Longworth. He made a sparkling wine from Catawba grapes. By 1855 Ohio had 1500 acres in vineyards, according to travel writer Frederick Law Olmsted, who said it was more than in Missouri and Illinois, which each had 1100 acres in wine.[11] German immigrants from the late 1840s had been instrumental in building the wine industry in those states.

In the 1860s, vineyards in the Ohio River Valley were attacked by Black rot. This prompted several winemakers to move north to the Finger Lakes region of western New York. During this time, the Missouri wine industry, centered on the German colony in Hermann, was expanding rapidly along both shores of the Missouri River west of St. Louis. By the end of the century, the state was second to California in wine production.[4] In the late 19th century, the phylloxera epidemic in the West and Pierce's disease in the East ravaged the American wine industry.[3]

Prohibition in the United States began when the state of Maine became the first state to go completely dry in 1846. Nationally, Prohibition was implemented after ratification by the states of the Eighteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution in 1920, which forbade the manufacturing, sale and transport of alcohol. Exceptions were made for sacramental wine used for religious purposes, and some wineries were able to maintain minimal production under those auspices, but most vineyards ceased operations. Others resorted to bootlegging. Home winemaking also became common, allowed through exemptions for sacramental wines and production for home use.[12]

Following the repeal of Prohibition in 1933, operators tried to revive the American wine making industry, which was nearly ended. Many talented winemakers had died, vineyards had been neglected or replanted with table grapes, and Prohibition had changed Americans' taste in wines. During the Great Depression, consumers demanded cheap "jug wine" (so-called dago red) and sweet, fortified (high alcohol) wine. Before Prohibition dry table wines outsold sweet wines by three to one, but afterward, the ratio of demand changed dramatically. As a result, by 1935, 81% of California's production was sweet wines. For decades, wine production was low and limited.

Leading the way to new methods of wine production was research conducted at the University of California, Davis and some of the state universities in New York. Faculty at the universities published reports on which varieties of grapes grew best in which regions, held seminars on winemaking techniques, consulted with grape growers and winemakers, offered academic degrees in viticulture, and promoted the production of quality wines. In the 1970s and 1980s, success by Californian winemakers in the northern part of the state helped to secure foreign investment from other winemaking regions, most notably the Champenois of France. Winemakers also cultivated vineyards in Oregon and Washington, on Long Island in New York, and numerous other new locales.

Americans became more educated about wines and increased their demand for high-quality wine. All 50 states now have some acreage in vineyard cultivation. By 2004, 668 million gallons (25.3 million hectoliters) of wine were consumed in the United States. California produces more than 88.5% of the wine, followed by New York, Washington and Oregon. In the second decade of the 21st century, the US wine industry faces the growing challenges of competition from international exports and managing domestic regulations on interstate sales and shipment of wine.[13]

Wine regions

There are nearly 3,000 commercial vineyards in the United States, and at least one winery in each of the 50 states.[14]

- West Coast – More than 90% of the total American wine production occurs in the states of California, Washington and Oregon.

- Rocky Mountain Region – Notably Idaho and Colorado

- Southwestern United States – Notably Texas and New Mexico

- Midwestern United States – Notably Missouri and Indiana

- Great Lakes region – Notably Michigan, northern New York and Ohio

- East Coast of the United States – Notably western New York State and eastern Long Island, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Virginia, North Carolina and Florida.

Production by state

Production of still wine per state in 2012 was as follows:[15]

| State | Production (gal) | Production (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Alabama | 31,312 | 0.004% |

| Arizona | 181,328 | 0.024% |

| California | 667,552,032 | 88.518% |

| Colorado | 334,089 | 0.046% |

| Connecticut | 122,628 | 0.016% |

| Florida | 1,946,162 | 0.258% |

| Georgia | 147,734 | 0.020% |

| Idaho | 315,615 | 0.042% |

| Illinois | 374,088 | 0.050% |

| Indiana | 1,069,775 | 0.142% |

| Iowa | 243,571 | 0.032% |

| Kansas | 68,504 | 0.009% |

| Kentucky | 2,379,512 | 0.316% |

| Maine | 43,136 | 0.006% |

| Maryland | 337,231 | 0.045% |

| Massachusetts | 268,911 | 0.036% |

| Michigan | 1,347,837 | 0.179% |

| Minnesota | 154,753 | 0.021% |

| Missouri | 1,034,917 | 0.270% |

| Montana | 18,375 | 0.002% |

| Nebraska | 81,641 | 0.011% |

| New Jersey | 1,561,365 | 0.207% |

| New Mexico | 742,873 | 0.099% |

| New York | 26,404,066 | 3.501% |

| North Carolina | 1,215,332 | 0.161% |

| Ohio | 3,048,054 | 0.404% |

| Oklahoma | 48,496 | 0.006% |

| Oregon | 6,829,808 | 0.906% |

| Pennsylvania | 3,589,603 | 0.476% |

| South Dakota | 19,373 | 0.003% |

| Tennessee | 296,436 | 0.039% |

| Texas | 1,376,144 | 0.182% |

| Virginia | 1,033,191 | 0.137% |

| Washington | 24,506,226 | 3.250% |

| West Virginia | 43,879 | 0.006% |

| Wisconsin | 612,885 | 0.081% |

| Others | 206,292 | 0.027% |

| Sum | 754,140,774 | 100 % |

Appellation system

The early American appellation system was based on the political boundaries of states and counties. In September 1978 the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms (now Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau) developed regulations to establish American Viticultural Areas (AVA) based on distinct climate and geographical features. In June 1980, the Augusta AVA in Missouri was established as the first American Viticultural Area under the new appellation system.[16] For the sake of wine labeling purposes, all the states and county appellations were grandfathered in as appellations. There were 187 distinct AVAs designated under U.S. law as of April 2007.[17]

Appellation labeling laws

In order to have an AVA appear on a wine label, at least 85% of the grapes used to produce the wine must be grown in the AVA.

With the larger state and county appellations the laws vary depending on the area. For a County Appellation, 75% of the grapes used must be from that county. If grapes are from two or three contiguous counties, a label can have a multi-county designation so long as the percentages used from each county are clearly on the label. For the majority of U.S. States the State Appellation requires 75% of the grapes in the wine to be grown in the state. Texas requires 85% and California requires 100%. If grapes are from two to three contiguous states a wine can be made under a multi-state designations following the same requirements as the multi-county appellation.

American wine or United States is a rarely used appellation that classifies a wine made from anywhere in the United States, including Puerto Rico and Washington, D.C.. Wines with this designation are similar to the French wine vin de table and can not include a vintage year. By law this is the only appellation allowed for bulk wines exported to other counties.[18]

Semi-generic wines

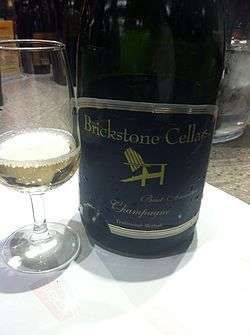

Current U.S. laws allow American made wines to be labeled as "American Burgundy" or "California champagne", even though these names are restricted in Europe. U.S. laws only restrict usage to include the qualifying area of origin to go with these semi-generic names. Other semi-generic names in the United States include Claret, Chablis, Chianti, Madeira, Malaga, Marsala, Moselle, Port, Rhine wine, Sauternes (commonly spelled on U.S. wine labels as Sauterne or Haut Sauterne), Sherry and Tokay. European Union officials have been working with their U.S. counterparts through World Trade Organization negotiations to eliminate the use of these semi-generic names.[18]

Fighting varietals

Fighting varietal is a term that originated in California during the late-1970s as a marketing response to combat overt pressure from European wine producers. The term was coined to separate traditional domestic jug wine, whimsical brands, and imports, from premium wine production in the U.S.[19]

The U.S. dollar in the early 1980s was trading with such historic strength, it was dominating world currency markets, eventually leading to the first coordinated agreement between Central Banks in 1985 to intervene and depreciate the Dollar in what is now termed the Plaza Accord. European wines with centuries of history supporting them found it easy to compete with wine production in the U.S. on quality since the U.S. had only decades in real development of its vineyards and wine production techniques. With better quality and lower price, European wines had a substantial advantage over domestic producers and could have crippled the development of the country's fine wine business without a change in tactics.

While European consumers understood the types of grapes grown in their regions, U.S. wine consumers found European labeling standards confusing. California wineries saw that as the opportunity and coordinated together to use varietals, the grapes in the bottle, as a means of educating the consumer and making the product easier to understand.

The actual term was coined referencing the "fight" against imported wines in the U.S. market using "varietals" instead of brands or regions for content identification.

While many different people have been given credit for the origination of the term, it is unlikely a conclusive author will ever be confirmed.

Other U.S. labeling laws

In the United States, at least 95% of grapes must be from a particular vintage for that year to appear on the label. Prior to the early 1970s, all grapes had to be from the vintage year. All labels must list the alcohol content based on percentage by volume. For bottles labeled by varietal at least 75% of the grape must be of the varietal. In Oregon, the requirement is 90%. American wine labels are also required to list if they contain sulfites and carry the Surgeon General's warning about alcohol consumption.[20]

Three-tier distribution

Following the repeal of Prohibition, the federal government allowed each state to regulate the production and sale of alcohol in their own state. For the majority of states this led to the development of a three-tier distribution system between the producer, wholesaler and consumer. Depending on the state there are some exceptions, with wineries allowed to sell directly to consumers on site at the winery.

Some states allow interstate sales through e-commerce. In the 2005 case of Granholm v. Heald, the Supreme Court of the United States struck down state laws banning interstate shipments but allowing in-state sales. The outcome of the Supreme Court decision was that states could decide to allow out of states wine sales along with in state sales or ban both altogether.[21]

Convenience stores and retail stores are large distributors of wine, with over 175,000 outlets that sell wine across the United States. In addition, there are around 332,000 other locations (bars, restaurants, etc.) that sell wine, contributing to the $30+ billion in annual sales over the past three years.[22] In 2010, the average monthly per-store sales of wine jumped to nearly $12,000 from $9,084 in 2009. The average gross margin dollars from wine increased to $3,324 from $2,616 in the year prior, with gross margin percentages up to an average 28.2 percent in 2010, versus 27 percent in 2009.[23]

Largest producers

As of 2005 The largest producers of American wine.[24]

- E & J Gallo Winery - Accounts for more than a quarter of all U.S. wine sales and is the second largest producer in the world.

- Constellation Brands - With foreign wine holdings Constellation is the largest producer in the world and includes Robert Mondavi Winery and Columbia Winery in its portfolio

- The Wine Group - San Francisco-based business which owns the Franzia box wine label, Concannon Vineyard and Mogen David kosher wine.

- Bronco Wine Company - Owners of the Charles Shaw wine "Two Buck Chuck" line which accounts for nearly 5 million of Bronco's annual average 9 million cases per year.

- Diageo - UK based company with American holdings in Sterling Vineyards, Beaulieu Vineyard and Chalone Vineyard

- Brown-Forman Corporation - Owners of the Korbel Champagne Cellars brand

- Beringer Blass - Australian based wine division of Foster's Group and owner of the Beringer wine and Stags' Leap Winery brands

- Jackson Wine Estates - Owners of the Kendall-Jackson brand

See also

References

- ↑ United States Department of Agriculture "Global Wine Report August 2006 Archived April 8, 2008, at the Wayback Machine.," pp. 7-9

- 1 2 T. Stevenson, The Sotheby's Wine Encyclopedia Fourth Edition, pg 462, Dorling Kindersly, 2005 ISBN 0-7566-1324-8

- 1 2 3 4 H. Johnson & J. Robinson The World Atlas of Wine pg 268 Mitchell Beazley Publishing 2005 ISBN 1-84000-332-4

- 1 2 3 4 J. Robinson, ed. The Oxford Companion to Wine, Third Edition p.719; Oxford University Press, 2006, ISBN 0-19-860990-6

- ↑ Littell's Laws of Kentucky Vol. 2, pp. 268-270

- ↑ The Swiss Settlement of Switzerland County, Indiana, page 293, Day Journal of J.J. Dufour

- ↑ Kentucky Gazette, March 29, 1803

- ↑ Library of Congress Doc#25644 Letters of Jefferson and Doc#25657 Letters of Jefferson

- ↑ John James Dufour, The Swiss Settlement of Switzerland County, Indiana, page XVII; and John James Dufour, The American Vine-Dressers Guide,page 10 ISBN 2-940289-00-X

- ↑ J. Robinson, ed. The Oxford Companion to Wine Third Edition, p.756; Oxford University Press, 2006, ISBN 0-19-860990-6

- ↑ Frederick Law Olmsted, A Journey through Texas (1859), pp. 6-7, at Open Library.org, Library of Congress

- ↑ Section 29 of the Volstead Act (27 U.S.C. § 46)

- ↑ J. Robinson, ed. The Oxford Companion to Wine Third Edition, p.720; Oxford University Press, 2006, ISBN 0-19-860990-6

- ↑ D. Shaw & A. Bahney, The New York Times (October 31, 2003) JOURNEYS; Welcome to Napa Nation

- ↑ Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau: Statistical Report – Wine (Reporting Period: January 2012 - December 2012), 6 May 2013

- ↑ H. Johnson & J. Robinson The World Atlas of Wine pg 269 Mitchell Beazley Publishing 2005 ISBN 1-84000-332-4

- ↑ Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau U.S. Viticultural Areas Updated as of 4/23/2007

- 1 2 T. Stevenson The Sotheby's Wine Encyclopedia Fourth Edition pg 464 Dorling Kindersly 2005 ISBN 0-7566-1324-8

- ↑ http://money.cnn.com/magazines/fortune/fortune_archive/1988/09/12/71016/index.htm

- ↑ T. Stevenson The Sotheby's Wine Encyclopedia Fourth Edition pg 465-466 Dorling Kindersly 2005 ISBN 0-7566-1324-8

- ↑ J. Robinson, ed. The Oxford Companion to Wine, Third Edition p.721; Oxford University Press, 2006, ISBN 0-19-860990-6

- ↑ "A Toast to Wine". SpareFoot. August 8, 2013. Retrieved January 5, 2014.

- ↑ NACS Magazine | Category Close Up: Pouring on the Profits

- ↑ T. Stevenson The Sotheby's Wine Encyclopedia Fourth Edition pg 468 Dorling Kindersly 2005 ISBN 0-7566-1324-8

Further reading

- Clarke, Oz. Oz Clarke's New Encyclopedia of Wine. NY: Harcourt Brace, 1999.

- Johnson, Hugh. Vintage: The Story of Wine. NY: Simon & Schuster, 1989.

- Taber, George M. Judgment of Paris: California vs. France and the Historic 1976 Paris Tasting that Revolutionized Wine. NY: Scribner, 2005.

External links

- Appellation America.com U.S. wine region and AVA portal

- All American Wineries U.S. winery and vineyard guide

- Free the Grapes: State wine shipment laws

- Doubtless as Good: Thomas Jefferson's Dream for American Wine Fulfilled An online exhibition from the National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution