United States Army Border Air Patrol

| United States Army Border Air Patrol | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Mexican Revolution, Border War | |||||

12th Aero Squadron Dayton-Wright DH-4 flying liaison with US Cavalry on United States/Mexico border patrol | |||||

| |||||

| Units involved | |||||

|

|

| ||||

With the end of World War I in 1918, the Air Service, United States Army was largely demobilized. During the demobilization period of 1919, the Regular Army and its air arm answered a call to defend the southern border against raids from Mexico, and to halt smuggling of illegal aliens and narcotics into the United States and weapons from the United States into Mexico.

Background

- see also Pancho Villa Expedition

Revolution and disorder in Mexico and trouble along the U.S.-Mexican border in March 1913 brought on the hurried organization of the 1st Aero Squadron, the U.S. Army’s first tactical unit equipped with airplanes. In 1916 the squadron took part in General Pershing’s Punitive Expedition into Mexico in pursuit of Mexican revolutionist Pancho Villa.[1]

Difficulties along the border continued during World War I while the United States was at war in Europe. Mexican bandits often raided American ranches to secure supplies, cattle, and horses, and in doing so sometimes killed the ranchers. U.S. troops stationed along the border shot raiders as they pursued them into Mexico. The biggest clash came in August 1918, when more than 800 American troops fought some 600 Mexicans near Nogales, Arizona.[1]

Border patrol was one of the many activities being considered for the postwar United States Army Air Service. However, no aviation units had been assigned to duty on the Mexican border, when a large force of Villistas moved northward in June 1919 toward Ciudad Juarez, Chihuahua, Mexico (opposite El Paso, Texas), garrisoned by Mexican government forces. Major General DeRosey C. Cabell, Commanding General of the Army Southern Department, received orders to seal off the border if Villa took Juarez. If the Villistas tired across the border, Cabell was to cross into Mexico, disperse Villa’s troops, and withdraw as soon as the safety of El Paso was assured. The general ordered Air Service men and planes from Kelly Field and Ellington Field, Texas, to Fort Bliss, near El Paso, for border patrol.[1]

American troops under Brig. Gen. James B. Erwin, Commander of the El Paso District of the Southern Department, were on alert when about 1,600 of Villa’s men attacked Juarez during the night of 14/15 June 1919. Stray fire from across the river killed an American soldier and a civilian, and wounded two other soldiers and four civilians. Around 3,600 U.S. troops crossed into Mexico, quickly dispersed the Villistas, and returned to the American side.[1][2][3]

Air Service surveillance mission

As a result of this incident, Air Service personnel equipped with war surplus Dayton-Wright DH-4 aircraft were ordered to Fort Bliss, Texas, on 15 June. Major Edgar G. Tobin, an ace who had flown with the 103d Aero Squadron in France, inaugurated an aerial patrol on the border on the 19th. By mid-September the force grew to 104 officers, 491 enlisted men, and 67 planes from the 8th Surveillance Squadron, 9th Corps Observation Squadron, 11th Aero Squadron, 90th Aero Squadron and the 96th Aero Squadron.[1][4]

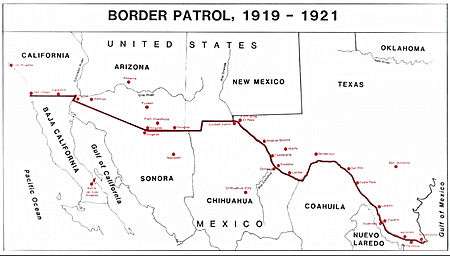

In the summer of 1919, the Air Service planned to assign at least nine Aero Squadrons and one Airship Company for surveillance of the entire Mexican border from the Gulf of Mexico to the Pacific Ocean. The original plan called for two Observation Squadrons (the 9th and 91st) of the Western Department to patrol eastward from Rockwell Field, California, to the California-Arizona line. Three Surveillance Squadrons (the 8th, 90th, and 104th) and four Bombardment Squadrons (the 1lth, 20th, 96th, and 166th) of the Southern Department were to be distributed along the border from Arizona to the Gulf of Mexico.[1]

On 1 July 1919, three surveillance squadrons were organized into the Army Surveillance Group (ASG) headquartered at Kelly Field. In September the four bombardment squadrons formed the 1st Day Bombardment Group, also with headquarters at Kelly Field. In addition the 1st Pursuit Group and its squadrons (27th, 94th, 95th, and 147th) were moved from Selfridge Field, Michigan, to Kelly at the end of August to be available if needed. The three groups (surveillance, day bombardment, and pursuit) comprised the 1st Wing at Kelly. Commanded by Lt. Col. Henry B. Clagett, the 1st Wing became responsible for aerial patrol of the border in the Southern Department. Also in August, work started on a large steel hangar for an airship station at Camp Owen Bierne, Fort Bliss (which later became part of Biggs Field).[1][5]

Operations

The Air Service soon scaled down the plan for border patrol. Although minor incidents continued to occur, Pancho Villa never succeeded in rebuilding his forces. The major threat had been dispelled by the time aerial patrol began. From January 1920 on, the mission of the Mexican Border Patrol in the Southern Department was assigned to the 1st Surveillance Group which had moved its headquarters to Fort Bliss and gained an extra squadron, the 12th. The group’s squadrons operated in two flights, each patrolling a sector on either side of its operating base.[1]

From the Gulf of Mexico westward, the deployment was as follows:[1][6]

|

|

Western Department Area:[1][7][8][9]

- Operated from: March Field and Rockwell Field, California, 22 July 1919 – 27 April 1920

- Flight operated from Calexico Field, California, 22 July 1919 – 1 April 1920

- Operated from: Ream Field, California, 24 January 1920

- Flight, or detachment thereof, operated from El Centro Field and Calexico Field, California, 17 March – 30 July 1920

- Squadron re-combined at: Rockwell Field, California, 30 April 1920

Both the 9th and 91st patrolled from the Pacific Coast at San Diego along the border to Yuma, Arizona.

The border patrol mission started with DH-4s and Curtiss JN-4 Jennies, with both eventually replaced with updated Dayton-Wright DH-4Bs. Most of the first planes were not properly equipped for field service. Not knowing what turn events on the border might take, the Army wanted the planes ready for any eventuality. Colonel James E. Fechet, Air Service Officer at the Southern Department, found it no easy task to obtain bomb racks, machine gun mounts, cameras, and other equipment. There was a delay, for example, in installing synchronized Martin guns because parts supplied with the guns did not fit the planes on the border. The radios on some planes could send only in code and could not do that very well. Compasses were unreliable, maps sketchy and of little use. The country over which the men had to fly was wild and rough and sparsely populated, with few places for safe emergency landings.[1][10][11]

Air Service squadrons flew along the border searching for bands of men and reported to the nearest cavalry post how many men they were, where they were, which way they were heading, what they were doing, and how many horses and cattle they had. The timing of the patrols varied so raiders would not know when the next plane would appear.[1][12][13]

Airfields

The patrol bases were hurriedly created. One of the young lieutenants who flew from Marfa Field in the summer of 1919 remembered the flying field as a pasture at the eastern edge of town. Its five hangars were made from canvas. A double row of ten or twelve tents served as officer and enlisted quarters and sheltered flight headquarters and supply. The lieutenant, Stacy C. Hinkle, recalled his tour of duty on the border as “a life of hardship, possible death, starvation pay, and a lonely life without social contacts, in hot, barren desert wastes, tortured by sun, wind, and sand.” The boredom was as bad as the physical hardship and discomfort, the sole recreation being drinking and gambling. Even so, Hinkle thought the airmen better off than the poor fellows at cavalry outposts up and down the border.[1][14][15]

Primary airfields used in the Border Patrol mission were:

|

|

Secondary airfields used on an as-needed bases, without garrisons, were at Bosque Bonite, Texas; Brownsville, Texas; Candelaria, Texas; Columbus Airfield, New Mexico; Fort Huachuca, Arizona; Lajitas, Texas; McAllen, Texas; Wellton, Arizona; Yuma, Arizona. and Zapata, Texas.

Border incidents

Pilots flying along or near the border were under orders not to cross. But they often got lost and strayed into Mexico. At times they went over deliberately, apparently on the spur of the moment. Occasionally, they crossed to carry out a special assignment.[1]

Addressing the National Congress of Mexico on 1 September 1919, President Venustiano Carranza said U.S. military planes had crossed the frontier several times. While his government had protested, the incursions had been repeated.[16] The Mexican president was probably not aware that one of the flights violating Mexico’s sovereignty had been made by the ranking pilot of the U.S. Air Service. Inspecting the border patrol in July 1919, General Billy Mitchell had taken Colonel Selah H.R. "Tommy" Tompkins, 7th Cavalry Commander, for a reconnaissance.[1][17][18]

In fact, the day President Carranza addressed the Mexican Congress, Ignacio Bonillas, Mexican Ambassador to the United States, protested the flight of two Air Service planes over Chihuahua City, during the afternoon of August 28. James B. Stewart, American Consul in Chihuahua, had already reported the incident. Soon Stewart was back with another dispatch and Bonillas was protesting again-more American planes had flown over Chihuahua on 2 September. Two more planes showed up in the morning of the 5th. When Stewart said these incidents embarrassed members of the American colony, Acting Secretary of State William Phillips replied: “War Department promises to issue strict orders against repetitions.“[1][19]

_-_Dayton-Wright_DH-4-2.jpg)

Not long afterward, Ambassador Bonillas complained that the crew of an Air Service airplane had fired a machine gun several times while flying over Nogales, Arizona. Some of the shots hit a dwelling across the border in Nogales, Sonora, luckily without injuring anyone. The Mexican government wanted the guilty persons found and punished. Several weeks later the State Department responded that an Air Service lieutenant was being tried by general court-martial for the shooting.[1][20]

Another incident protested by the Mexican government began with two Americans getting lost while on a routine flight in the Big Bend area of Texas on Sunday morning, 10 August 1919. A flyer might easily get lost on patrol. Lts. Harold G. Peterson, pilot, and Paul H. Davis, observer-gunner from Marfa Field, Texas, found it could happen while following a river on a clear day. Their mission was to patrol along the Rio Grande from Lajitas to Bosque Bonito and then land at Fort Bliss. Coming to the mouth of the Rio Conchos at Ojinaga, Chihuahua, they mistook the Conches for the Rio Grande and followed it many miles into Mexico before being forced down by engine trouble. Thinking they were still on the Rio Grande, the airmen picked a spot on the “American” side of the river to land. The terrain was rough and the plane was wrecked. Having buried the machine guns and ammunition to keep them out of the hands of bandits, Peterson and Davis started walking down the river, thinking they would come to the U.S. Cavalry outpost at Candelaria, Texas.[1]

When Peterson and Davis did not arrive at Fort Bliss on Sunday afternoon, the men there assumed they had either returned to Marfa Field or made a forced landing. When they were unaccounted for on Monday, a search was begun. Flying over the patrol route, 1st Lts. Frank Estell and Russell H. Cooper surmised that Peterson and Davis might have mistakenly followed the Conches into Mexico. The region along the Conches almost as far as Chihuahua City was added to the area covered by search planes. Tuesday afternoon Peterson and Davis saw a plane flying up the Conches, but they were in thick brush and could not attract the crew’s attention. The search continued until Sunday, 17 August 1919. Then Capt. Leonard F. Matlack, commanding Troop K, 8th Cavalry, at Candelaria, received word Peterson and Davis were being held for ransom.[1]

_-_Dayton-Wright_DH-4.jpg)

The flyers had been taken prisoner on Wednesday, 13 August by a Villista desperado named Jesus Renteria. The bandit sent the ransom note to a rancher at Candelaria, along with telegrams which he forced the airmen to write to their fathers and the Secretary of War, the Commanding General of the Southern Department, and the commanding officer of U.S. forces in the Big Bend District. Renteria demanded $15,000 not later than Monday, 18 August, or the two Americans would be killed.[1]

The War Department authorized payment of the ransom, but there remained the matter of getting $15,000 in cash for delivery before the deadline. Ranchers in the area quickly subscribed the full amount, which came from the Marfa National Bank. Negotiation through intermediaries resulted in a plan for Captain Matlack to cross the border Monday night with half of the ransom money for the release of one of the Americans. The meeting took place on schedule, and within forty-five minutes Matlack came back with Lieutenant Peterson.[1]

Matlack then took the remaining $7,500 to get Lieutenant Davis. On the way to the rendezvous he overheard two of Renteria’s men talking about killing him and Davis as soon as the rest of the ransom money was paid. At the rendezvous, Matlack pulled a gun, told the Mexicans to tell Renteria to “go to hell,” and rode off with Davis and the money. Avoiding the ambush, Matlack and Davis safely crossed into the United States. Questioned by Col. George T. Langhome, Army Commander in the Big Bend District, Peterson and Davis maintained they had been captured on the American side of the border and had not crossed into Mexico.[1]

At daybreak on Tuesday, August 19, 1919, Captain Matlack once again crossed the border, this time leading Troops C and K, 8th Cavalry, in pursuit of Renteria and his gang. Air Service planes scouted ahead of the cavalry seeking to spot the bandits. They also gathered information on the condition of the trails and the location of waterholes, and conveyed it to the troops by dropping messages.[1]

While flying some twelve or fifteen miles west of Candelaria late Tuesday afternoon, Lieutenants Estell and Cooper saw three horsemen in a canyon and went lower for a better look. When the men on the ground fired on the DH-4, Estell made another pass with his machine guns blazing. Then Cooper opened up with his Lewis Guns and killed one of the men, reportedly Renteria.[1]

The search for members of Renteria’s gang continued until 23 August. With the Mexican government protesting the invasion of its territory, American forces returned to the United States.[1][21][22]

A few months later another plane landed in Mexico after its crew followed the wrong railroad tracks. Patrolling on Monday, 2 February 1920, 1st Lts. Leroy M. Wolfe and George L. Usher intended to pick up the El Paso and Southwestern Railroad west of Douglas, Arizona, and follow it to Nogales. Visibility was poor and the compass did not work properly. Sighting a railroad, Wolfe and Usher followed it for some time until it ended. Lost and having engine trouble, they landed and were taken into custody by Mexican officials. The tracks they had steered by ran due south instead of west, and had led them to Nacozari, Sonora, seventy-five or eighty miles below the border. Though treated well, Wolfe and Usher were not set free until 2 February. They waited three more days for release of their airplane, shipping it to Douglas by train.[1][23]

On border patrol with the 9th Corps Observation Squadron, Lts. Frederick Waterhouse and Cecil H. Connolly disappeared after taking off from Calexico Field, California, bound for Rockwell Field, on 20 August 1919. A search begun the next morning gradually extended farther and farther south in Baja California. When three weeks passed with no trace of the missing men, the search ended. A month later it was learned their bodies had been found near Bahía de los Ángeles on the coast of the Gulf of California, 225 miles south of Calexico.[1]

From the evidence that could be gathered, it appeared Waterhouse and Connolly became lost in a rainstorm and hugged the coast of Baja California southward, thinking they were headed north along the Pacific Coast. They landed safely on the beach about twenty miles north of Bahia de Los Angeles. Their sole chance for survival seemed to be staying with the plane until found. Tortured by heat, thirst, and hunger, they waited seventeen days, but the search never reached that far south. Finally two fishermen came along and took them in a canoe to Bahia de Los Angeles. There the Americans were murdered, apparently for the little money they had. Their bodies, buried in the sand, were discovered within a day or two by an American geological survey party and rediscovered a week later by an American mining engineer. The news, however, did not reach Rockwell Field until 13 October. Three days later, a Navy ship, USS Aaron Ward, sailed from San Diego with a group of Army officers to recover the bodies.[1][24][25]

Conclusion

As time went on, air border units spent less time on patrol and more in training with the Army infantry, artillery, and cavalry units. Air Service personnel further practiced aerial gunnery and formation flying, experimented with radio and other signaling systems, located and marked emergency landing fields, and worked to upgrade facilities and equipment.[1][26]

At first, units tried to cover their sectors every day. Later, the number and seriousness of border violations by Mexicans decreased, and the patrols tapered off. In the autumn of 1920, the schedule for the 1st Surveillance Group called for flights twice a week. When exercises with ground forces or other activities interfered, patrols might be canceled for days or even weeks at a time. Brig. Gen. William Mitchell’s need for men and planes from the border for bombing tests against naval vessels off the Virginia Capes in June 1921 brought border patrol to an end.[1][27]

References

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from the Air Force Historical Research Agency website http://www.afhra.af.mil/.

This article incorporates public domain material from the Air Force Historical Research Agency website http://www.afhra.af.mil/.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 Maurer, Maurer (1987), Aviation in the US. Army, 1919– 1939, United States Air Force Historical Research Center, Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama. ISBN 0-912799-38-2

- ↑ Army Hist Div, Order of Battle, 111, pt 1, 610–11.

- ↑ Clarence C. Clendenen, Blood on the Border: The United States Army and the Mexican Irregulars (London, 1969), pp 351–355

- ↑ Clay, Steven E. (2011), US Army Order of Battle 1919–1941. 2 The Services: Air Service, Engineers, and Special Troops 1919–1941. Fort Leavenworth, KS: Combat Studies Institute Press. ISBN 9780984190140.

- ↑ ASNLs, Sep 3, 1919, pp 1–2, Dec 3, 1919, p 1.

- ↑ Maurer, Maurer, ed. (1982) [1969]. Combat Squadrons of the Air Force, World War II (PDF) (reprint ed.). Washington, DC: Office of Air Force History. ISBN 0-405-12194-6. LCCN 70605402. OCLC 72556.

- ↑ Stacy C. Hinkle, Wings Over the Border: The Army Air Service Armed Patrol of the United States-Mexican Border, 1919–1921 (El Paso, 1970), pp 6–9.

- ↑ Jones Chronology, Jun 18, 1919.

- ↑ Maurer, Combat Squadrons. Maps of the Army’s patrol districts are found in Army Historical Division, Order of Battle, 111, part 1, following pages 606, 608, and 616.

- ↑ ASNL, Sep 3, 1919, pp 1–2.

- ↑ Hinkle, Wings Over the Border, pp 13–18, 22.

- ↑ Hinkle, Wings Over the Border, pp 10–12.

- ↑ Maj Henry H. Arnold, History of Rockwell Field (1923), p 87, MS in AFHRC 168.65041

- ↑ Stacy C. Hinkle, Wings and Saddles: The Air and Cavalry Punitive Expedition of 1919 (El Paso, 1967), pp 8, 34.

- ↑ Hinkle, Wings Over the Border, p 8.

- ↑ Papers Relating to the Foreign Relations of the United States, 1919 (Washington: Department of State, 1934), 11, 537.

- ↑ 11. Hinkle, Wings Over the Border, pp 18-19.

- ↑ Burke Davis, The Billy Mitchell Affair (New York, 1967), pp 55–56.

- ↑ Foreign Relations, 1919, 11, 561–62.

- ↑ Foreign Relations, 1919, 11, 564-65.

- ↑ Hinkle, Wings and Saddles, passim.

- ↑ Lt Harold G. Peterson and Lt Paul H. Davis, “Held for Ransom in Mexico,” US. Air Service, I1 (Oct, 1919), 16–19.

- ↑ Hinkle, Wings Over the Border, pp 47–48.

- ↑ Hinkle, Wings Over the Border, pp 26–36.

- ↑ Arnold, History of Rockwell Field (1923), pp 87–91. The full story of this incident is yet to be written.

- ↑ Hinkle, Wings Over the Border, pp 20–21.

- ↑ The 12th Observation Squadron, at Fort Bliss until 1926, sporadically flew patrols along the border during that time