Vasilisa the Beautiful

Vasilisa the Beautiful (Russian: Василиса Прекрасная) is a Russian fairy tale collected by Alexander Afanasyev in Narodnye russkie skazki.[1]

Synopsis

By his first wife, a merchant had a single daughter, who was known as Vasilisa the Beautiful. When the girl was eight years old, her mother died. On her deathbed, she gave Vasilisa a tiny wooden doll with instructions to give it a little to eat and a little to drink if she were in need, and then it would help her. As soon as her mother died, Vasilisa gave it a little to drink and a little to eat, and it comforted her.

After a time, her father remarried; the new wife was a woman with two daughters. Vasilisa's stepmother was very cruel to her, but with the help of the doll, she was able to perform all the tasks imposed on her. When young men came wooing, the stepmother rejected them all because it was not proper for the younger to marry before the older, and none of the suitors wished to marry Vasilisa's stepsisters.

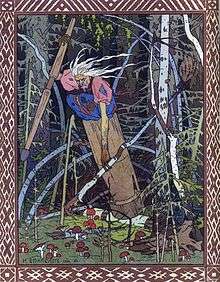

One day the merchant had to embark on a journey. His wife sold the house and moved them all to a gloomy hut by the forest. One day she gave each of the girls a task and put out all the fires except a single candle. Her older daughter then put out the candle, whereupon they sent Vasilisa to fetch light from Baba Yaga's hut. The doll advised her to go, and she went. While she was walking, a mysterious man rode by her in the hours before dawn, dressed in white, riding a white horse whose equipment was all white; then a similar rider in red. She came to a house that stood on chicken legs and was walled by a fence made of human bones. A black rider, like the white and red riders, rode past her, and night fell, whereupon the eye sockets of the skulls began to glow. Vasilisa was too frightened to run away, and so Baba Yaga found her when she arrived in her mortar.

Baba Yaga said that Vasilisa must perform tasks to earn the fire, or be killed. She was to clean the house and yard, wash Baba Yaga's laundry, and cook her a meal. She was also required to separate grains of rotten corn from sound corn, and separate poppy seeds from grains of soil. Baba Yaga left, and Vasilisa despaired, as she worked herself into exhaustion. When all hope of completing the tasks seemed lost, the doll whispered that she would complete the tasks for Vasilisa, and that the girl should sleep.

At dawn, the white rider passed; at or before noon, the red. As the black rider rode past, Baba Yaga returned and could complain of nothing. She bade three pairs of disembodied hands seize the corn to squeeze the oil from it, then asked Vasilisa if she had any questions.

Vasilisa asked about the riders's identities and was told that the white one was Day, the red one the Sun, and the black one Night. But when Vasilisa thought of asking about the disembodied hands, the doll quivered in her pocket. Vasilisa realized she should not ask, and told Baba Yaga she had no further questions. In return, Baba Yaga enquired as to the cause of Vasilisa's success. On hearing the answer "by my mother's blessing," Baba Yaga, who wanted nobody with any kind of blessing in her presence, threw Vasilisa out of her house, and sent her home with a skull-lantern full of burning coals, to provide light for her step-family.

Upon her return, Vasilisa found that, since sending her out on her task, her step-family had been unable to light any candles or fire in their home. Even lamps and candles that might be brought in from outside were useless for the purpose, as all were snuffed out the second they were carried over the threshold. The coals brought in the skull-lantern burned Vasilisa's stepmother and stepsisters to ashes, and Vasilisa buried the skull according to its instructions, so no person would ever be harmed by it. [2]

Later, Vasilisa became an assistant to a maker of cloth in Russia's capital city, where she became so skilled at her work that the Tsar himself noticed her skill; he later married Vasilisa.

Variants

In some versions, the tale ends with the death of the stepmother and stepsisters, and Vasilisa lives peacefully with her new husband (the czar) and her father after their removal. This is unusual in a tale with a grown heroine, although some, such as Jack and the Beanstalk, do feature it.[3]

Interpretations

The white, red, and black riders appear in other tales of Baba Yaga and are often interpreted to give her a mythological significance.

In common with many folklorists of his day, Alexander Afanasyev regarded many tales as primitive ways of viewing nature. In such an interpretation, he regarded this fairy tale as depicting the conflict between the sunlight (Vasilisa), the storm (her stepmother), and dark clouds (her stepsisters).[4]

Clarissa Pinkola Estés interprets the story as a tale of female liberation, Vasilisa's journey from subservience to strength and independence. She interprets Baba Yaga as the "wild feminine" principle that Vasilisa has been separated from, which, by obeying and learning how to nurture, she learns and grows from.[5]

Related and eponymous works

Aleksandr Rou made a film entitled Vasilisa the Beautiful in 1939, however, it was based on a different tale – The Frog Tsarevna.[6] American author Elizabeth Winthrop wrote a children's book – Vasilissa the Beautiful: a Russian Folktale (HarperCollins, 1991), illustrated by Alexander Koshkin. There is also a Soviet cartoon – Vasilisa the Beautiful, but it is also based on the Frog Tsarevna tale.

Vasilisa appears in the 2007 comic book Hellboy: Darkness Calls to assist Hellboy against Koschei the deathless with her usual story of the Baba Yaga . The book also includes other characters of slavic folklore, such as a domiov making an appearance.

See also

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Vasilisa the Beautiful (Bilibin). |

- ↑ Alexander Afanasyev, Narodnye russkie skazki, "Vasilissa the Beautiful"

- ↑ Santo, Suzanne Banay (2012). Returning: A Tale of Vasilisa and Baba Yaga. Toronto, Ontario, Canada: Red Butterfly Publications. p. 24. ISBN 9781475236019.

- ↑ Maria Tatar, Off with Their Heads! p. 199 ISBN 0-691-06943-3

- ↑ Maria Tatar, p 334, The Annotated Classic Fairy Tales, ISBN 0-393-05163-3

- ↑ Estés, Clarissa Pinkola (1992). Women Who Run with the Wolves. Ballantine Books. ISBN 978-0-345-40987-4.

- ↑ James Graham, "Baba Yaga in Film"