Pandemic

A pandemic (from Greek πᾶν pan "all" and δῆμος demos "people") is an epidemic of infectious disease that has spread through human populations across a large region; for instance multiple continents, or even worldwide. A widespread endemic disease that is stable in terms of how many people are getting sick from it is not a pandemic. Further, flu pandemics generally exclude recurrences of seasonal flu. Throughout history, there have been a number of pandemics, such as smallpox and tuberculosis. One of the most devastating pandemics was the Black Death, killing over 75 million people in 1350. The most recent pandemics include the HIV pandemic as well as the 1918 and 2009 H1N1 pandemics.

Definition and stages

A pandemic is an epidemic occurring on a scale which crosses international boundaries, usually affecting a large number of people.[1]

The World Health Organization (WHO) has a six-stage classification that describes the process by which a novel influenza virus moves from the first few infections in humans through to a pandemic. This starts with the virus mostly infecting animals, with a few cases where animals infect people, then moves through the stage where the virus begins to spread directly between people, and ends with a pandemic when infections from the new virus have spread worldwide and it will be out of control until we stop it.[2]

A disease or condition is not a pandemic merely because it is widespread or kills many people; it must also be infectious. For instance, cancer is responsible for many deaths but is not considered a pandemic because the disease is not infectious or contagious.

In a virtual press conference in May 2009 on the influenza pandemic, Dr Keiji Fukuda, Assistant Director-General ad interim for Health Security and Environment, WHO said "An easy way to think about pandemic … is to say: a pandemic is a global outbreak. Then you might ask yourself: 'What is a global outbreak'? Global outbreak means that we see both spread of the agent … and then we see disease activities in addition to the spread of the virus."[3]

In planning for a possible influenza pandemic, the WHO published a document on pandemic preparedness guidance in 1999, revised in 2005 and in February 2009, defining phases and appropriate actions for each phase in an aide memoir entitled WHO pandemic phase descriptions and main actions by phase. The 2009 revision, including definitions of a pandemic and the phases leading to its declaration, were finalized in February 2009. The pandemic H1N1 2009 virus was neither on the horizon at that time nor mentioned in the document.[4][5] All versions of this document refer to influenza. The phases are defined by the spread of the disease; virulence and mortality are not mentioned in the current WHO definition, although these factors have previously been included.[6]

Current pandemics

HIV and AIDS

HIV originated in Africa, and spread to the United States via Haiti between 1966 and 1972.[7] AIDS is currently a pandemic, with infection rates as high as 25% in southern and eastern Africa. In 2006, the HIV prevalence rate among pregnant women in South Africa was 29.1%.[8] Effective education about safer sexual practices and bloodborne infection precautions training have helped to slow down infection rates in several African countries sponsoring national education programs. Infection rates are rising again in Asia and the Americas. The AIDS death toll in Africa may reach 90–100 million by 2025.[9]

Pandemics and notable epidemics through history

There have been a number of significant pandemics recorded in human history, generally zoonoses which came about with domestication of animals, such as influenza and tuberculosis. There have been a number of particularly significant epidemics that deserve mention above the "mere" destruction of cities:

- Plague of Athens, 430 BC. Possibly typhoid fever killed a quarter of the Athenian troops, and a quarter of the population over four years. This disease fatally weakened the dominance of Athens, but the sheer virulence of the disease prevented its wider spread; i.e. it killed off its hosts at a rate faster than they could spread it. The exact cause of the plague was unknown for many years. In January 2006, researchers from the University of Athens analyzed teeth recovered from a mass grave underneath the city, and confirmed the presence of bacteria responsible for typhoid.[10]

- Antonine Plague, 165–180 AD. Possibly smallpox brought to the Italian peninsula by soldiers returning from the Near East; it killed a quarter of those infected, and up to five million in all.[11] At the height of a second outbreak, the Plague of Cyprian (251–266), which may have been the same disease, 5,000 people a day were said to be dying in Rome.

- Plague of Justinian, from 541 to 750, was the first recorded outbreak of the bubonic plague. It started in Egypt, and reached Constantinople the following spring, killing (according to the Byzantine chronicler Procopius) 10,000 a day at its height, and perhaps 40% of the city's inhabitants. The plague went on to eliminate a quarter to a half of the human population that it struck throughout the known world.[12][13] It caused Europe's population to drop by around 50% between 550 and 700.[14]

- Black Death, from 1347 to 1453. The total number of deaths worldwide is estimated at 75 million people.[15] Eight hundred years after the last outbreak, the plague returned to Europe. Starting in Asia, the disease reached Mediterranean and western Europe in 1348 (possibly from Italian merchants fleeing fighting in Crimea), and killed an estimated 20 to 30 million Europeans in six years;[16] a third of the total population,[17] and up to a half in the worst-affected urban areas.[18] It was the first of a cycle of European plague epidemics that continued until the 18th century.[19] There were more than 100 plague epidemics in Europe in this period.[20] The disease recurred in England every two to five years from 1361 to 1480.[21] By the 1370s, England's population was reduced by 50%.[22] The Great Plague of London of 1665–66 was the last major outbreak of the plague in England. The disease killed approximately 100,000 people, 20% of London's population.[23]

- The third plague pandemic started in China in 1855, and spread to India, where 10 million people died.[24] During this pandemic, the United States saw its first outbreak: the San Francisco plague of 1900–1904.[25] Today, isolated cases of plague are still found in the western United States.[26]

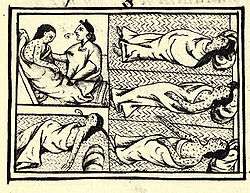

Encounters between European explorers and populations in the rest of the world often introduced local epidemics of extraordinary virulence. Disease killed part of the native population of the Canary Islands in the 16th century (Guanches). Half the native population of Hispaniola in 1518 was killed by smallpox. Smallpox also ravaged Mexico in the 1520s, killing 150,000 in Tenochtitlán alone, including the emperor, and Peru in the 1530s, aiding the European conquerors.[27] Measles killed a further two million Mexican natives in the 17th century. In 1618–1619, smallpox wiped out 90% of the Massachusetts Bay Native Americans.[28] During the 1770s, smallpox killed at least 30% of the Pacific Northwest Native Americans.[29] Smallpox epidemics in 1780–1782 and 1837–1838 brought devastation and drastic depopulation among the Plains Indians.[30] Some believe that the death of up to 95% of the Native American population of the New World was caused by Old World diseases such as smallpox, measles, and influenza.[31] Over the centuries, the Europeans had developed high degrees of immunity to these diseases, while the indigenous peoples had no such immunity.[32]

Smallpox devastated the native population of Australia, killing around 50% of Indigenous Australians in the early years of British colonisation.[33] It also killed many New Zealand Māori.[34] As late as 1848–49, as many as 40,000 out of 150,000 Hawaiians are estimated to have died of measles, whooping cough and influenza. Introduced diseases, notably smallpox, nearly wiped out the native population of Easter Island.[35] In 1875, measles killed over 40,000 Fijians, approximately one-third of the population.[36] The disease devastated the Andamanese population.[37] Ainu population decreased drastically in the 19th century, due in large part to infectious diseases brought by Japanese settlers pouring into Hokkaido.[38]

Researchers concluded that syphilis was carried from the New World to Europe after Columbus' voyages. The findings suggested Europeans could have carried the nonvenereal tropical bacteria home, where the organisms may have mutated into a more deadly form in the different conditions of Europe.[39] The disease was more frequently fatal than it is today. Syphilis was a major killer in Europe during the Renaissance.[40] Between 1602 and 1796, the Dutch East India Company sent almost a million Europeans to work in Asia. Ultimately, only less than one-third made their way back to Europe. The majority died of diseases.[41] Disease killed more British soldiers in India than war.[42]

As early as 1803, the Spanish Crown organized a mission (the Balmis expedition) to transport the smallpox vaccine to the Spanish colonies, and establish mass vaccination programs there.[43] By 1832, the federal government of the United States established a smallpox vaccination program for Native Americans.[44] From the beginning of the 20th century onwards, the elimination or control of disease in tropical countries became a driving force for all colonial powers.[45] The sleeping sickness epidemic in Africa was arrested due to mobile teams systematically screening millions of people at risk.[46] In the 20th century, the world saw the biggest increase in its population in human history due to lessening of the mortality rate in many countries due to medical advances.[47] The world population has grown from 1.6 billion in 1900 to an estimated 7 billion today.[48]

Cholera

Since it became widespread in the 19th century, cholera has killed tens of millions of people.[49]

- First cholera pandemic 1816–1826. Previously restricted to the Indian subcontinent, the pandemic began in Bengal, then spread across India by 1820. 10,000 British troops and countless Indians died during this pandemic.[50] It extended as far as China, Indonesia (where more than 100,000 people succumbed on the island of Java alone) and the Caspian Sea before receding. Deaths in India between 1817 and 1860 are estimated to have exceeded 15 million persons. Another 23 million died between 1865 and 1917. Russian deaths during a similar period exceeded 2 million.[51]

- Second cholera pandemic 1829–1851. Reached Russia (see Cholera Riots), Hungary (about 100,000 deaths) and Germany in 1831, London in 1832 (more than 55,000 persons died in the United Kingdom),[52] France, Canada (Ontario), and United States (New York City) in the same year,[53] and the Pacific coast of North America by 1834. A two-year outbreak began in England and Wales in 1848 and claimed 52,000 lives.[54] It is believed that over 150,000 Americans died of cholera between 1832 and 1849.[55]

- Third pandemic 1852–1860. Mainly affected Russia, with over a million deaths. Throughout Spain, cholera caused more than 236,000 deaths in 1854–55.[56] It claimed 200,000 lives in Mexico.[57]

- Fourth pandemic 1863–1875. Spread mostly in Europe and Africa. At least 30,000 of the 90,000 Mecca pilgrims fell victim to the disease. Cholera claimed 90,000 lives in Russia in 1866.[58]

- In 1866, there was an outbreak in North America. It killed some 50,000 Americans.[55]

- Fifth pandemic 1881–1896. The 1883–1887 epidemic cost 250,000 lives in Europe and at least 50,000 in Americas. Cholera claimed 267,890 lives in Russia (1892);[59] 120,000 in Spain;[60] 90,000 in Japan and 60,000 in Persia.

- In 1892, cholera contaminated the water supply of Hamburg, and caused 8,606 deaths.[61]

- Sixth pandemic 1899–1923. Had little effect in Europe because of advances in public health, but Russia was badly affected again (more than 500,000 people dying of cholera during the first quarter of the 20th century).[62] The sixth pandemic killed more than 800,000 in India. The 1902–1904 cholera epidemic claimed over 200,000 lives in the Philippines.[63]

- Seventh pandemic 1962–66. Began in Indonesia, called El Tor after the strain, and reached Bangladesh in 1963, India in 1964, and the USSR in 1966.

Influenza

- The Greek physician Hippocrates, the "Father of Medicine", first described influenza in 412 BC.[64]

- The first influenza pandemic was recorded in 1580, and since then, influenza pandemics occurred every 10 to 30 years.[65][66][67]

- The 1889–1890 flu pandemic, also known as Russian Flu, was first reported in May 1889 in Bukhara, Uzbekistan. By October, it had reached Tomsk and the Caucasus. It rapidly spread west and hit North America in December 1889, South America in February–April 1890, India in February–March 1890, and Australia in March–April 1890. The H3N8 and H2N2 subtypes of the Influenza A virus have each been identified as possible causes. It had a very high attack and mortality rate, causing around a million fatalities.[68]

- The "Spanish flu", 1918–1919. First identified early in March 1918 in US troops training at Camp Funston, Kansas. By October 1918, it had spread to become a worldwide pandemic on all continents, and eventually infected about one-third of the world's population (or ≈500 million persons).[69] Unusually deadly and virulent, it ended nearly as quickly as it began, vanishing completely within 18 months. In six months, some 50 million were dead;[69] some estimates put the total of those killed worldwide at over twice that number.[70] About 17 million died in India, 675,000 in the United States[71] and 200,000 in the UK. The virus was recently reconstructed by scientists at the CDC studying remains preserved by the Alaskan permafrost. The H1N1 virus has a small, but crucial structure that is similar to the Spanish Flu.[72]

- The "Asian Flu", 1957–58. An H2N2 virus caused about 70,000 deaths in the United States. First identified in China in late February 1957, the Asian flu spread to the United States by June 1957. It caused about 2 million deaths globally.[73]

- The "Hong Kong Flu", 1968–69. An H3N2 caused about 34,000 deaths in the United States. This virus was first detected in Hong Kong in early 1968, and spread to the United States later that year. This pandemic of 1968 and 1969 killed approximately one million people worldwide. Influenza A (H3N2) viruses still circulate today.

Typhus

Typhus is sometimes called "camp fever" because of its pattern of flaring up in times of strife. (It is also known as "gaol fever" and "ship fever", for its habits of spreading wildly in cramped quarters, such as jails and ships.) Emerging during the Crusades, it had its first impact in Europe in 1489, in Spain. During fighting between the Christian Spaniards and the Muslims in Granada, the Spanish lost 3,000 to war casualties, and 20,000 to typhus. In 1528, the French lost 18,000 troops in Italy, and lost supremacy in Italy to the Spanish. In 1542, 30,000 soldiers died of typhus while fighting the Ottomans in the Balkans.

During the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648), about 8 million Germans were killed by bubonic plague and typhus.[74] The disease also played a major role in the destruction of Napoleon's Grande Armée in Russia in 1812. During the retreat from Moscow, more French military personnel died of typhus than were killed by the Russians.[75] Of the 450,000 soldiers who crossed the Neman on 25 June 1812, fewer than 40,000 returned. More military personnel were killed from 1500–1914 by typhus than from military action.[76] In early 1813, Napoleon raised a new army of 500,000 to replace his Russian losses. In the campaign of that year, over 219,000 of Napoleon's soldiers died of typhus.[77] Typhus played a major factor in the Irish Potato Famine. During World War I, typhus epidemics killed over 150,000 in Serbia. There were about 25 million infections and 3 million deaths from epidemic typhus in Russia from 1918 to 1922.[77] Typhus also killed numerous prisoners in the Nazi concentration camps and Soviet prisoner of war camps during World War II. More than 3.5 million Soviet POWs died out of the 5.7 million in Nazi custody.[78]

Smallpox

Smallpox is a highly contagious disease caused by the variola virus. The disease killed an estimated 400,000 Europeans per year during the closing years of the 18th century.[79] During the 20th century, it is estimated that smallpox was responsible for 300–500 million deaths.[80][81] As recently as the early 1950s, an estimated 50 million cases of smallpox occurred in the world each year.[82] After successful vaccination campaigns throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, the WHO certified the eradication of smallpox in December 1979. To this day, smallpox is the only human infectious disease to have been completely eradicated,[83] and one of two infectious viruses ever to be eradicated.[84]

Measles

Historically, measles was prevalent throughout the world, as it is highly contagious. According to the U.S. National Immunization Program, 90% of people were infected with measles by age 15. Before the vaccine was introduced in 1963, there were an estimated 3–4 million cases in the U.S. each year.[85] Measles killed around 200 million people worldwide over the last 150 years.[86] In 2000 alone, measles killed some 777,000 worldwide out of 40 million cases globally.[87]

Measles is an endemic disease, meaning that it has been continually present in a community, and many people develop resistance. In populations that have not been exposed to measles, exposure to a new disease can be devastating. In 1529, a measles outbreak in Cuba killed two-thirds of the natives who had previously survived smallpox.[88] The disease had ravaged Mexico, Central America, and the Inca civilization.[89]

Tuberculosis

One-third of the world's current population has been infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis, and new infections occur at a rate of one per second.[90] About 5–10% of these latent infections will eventually progress to active disease, which, if left untreated, kills more than half of its victims. Annually, 8 million people become ill with tuberculosis, and 2 million people die from the disease worldwide.[91] In the 19th century, tuberculosis killed an estimated one-quarter of the adult population of Europe;[92] by 1918, one in six deaths in France were still caused by tuberculosis. During the 20th century, tuberculosis killed approximately 100 million people.[86] TB is still one of the most important health problems in the developing world.[93]

Leprosy

Leprosy, also known as Hansen's disease, is caused by a bacillus, Mycobacterium leprae. It is a chronic disease with an incubation period of up to five years. Since 1985, 15 million people worldwide have been cured of leprosy.[94]

Historically, leprosy has affected people since at least 600 BC.[95] Leprosy outbreaks began to occur in Western Europe around 1000 AD.[96][97] Numerous leprosaria, or leper hospitals, sprang up in the Middle Ages; Matthew Paris estimated that in the early 13th century, there were 19,000 of them across Europe.[98]

Malaria

Malaria is widespread in tropical and subtropical regions, including parts of the Americas, Asia, and Africa. Each year, there are approximately 350–500 million cases of malaria.[99] Drug resistance poses a growing problem in the treatment of malaria in the 21st century, since resistance is now common against all classes of antimalarial drugs, except for the artemisinins.[100]

Malaria was once common in most of Europe and North America, where it is now for all purposes non-existent.[101] Malaria may have contributed to the decline of the Roman Empire.[102] The disease became known as "Roman fever".[103] Plasmodium falciparum became a real threat to colonists and indigenous people alike when it was introduced into the Americas along with the slave trade. Malaria devastated the Jamestown colony and regularly ravaged the South and Midwest of the United States. By 1830, it had reached the Pacific Northwest.[104] During the American Civil War, there were over 1.2 million cases of malaria among soldiers of both sides.[105] The southern U.S. continued to be afflicted with millions of cases of malaria into the 1930s.[106]

Yellow fever

Yellow fever has been a source of several devastating epidemics.[107] Cities as far north as New York, Philadelphia, and Boston were hit with epidemics. In 1793, one of the largest yellow fever epidemics in U.S. history killed as many as 5,000 people in Philadelphia—roughly 10% of the population. About half of the residents had fled the city, including President George Washington.[108] In colonial times, West Africa became known as "the white man's grave" because of malaria and yellow fever.[109]

Zika virus

Concern about possible future pandemics

Viral hemorrhagic fevers

Viral hemorrhagic fevers such as Ebola Virus Disease, Lassa fever virus, Rift Valley fever, Marburg Virus and Bolivian hemorrhagic fever are highly contagious and deadly diseases, with the theoretical potential to become pandemics. Their ability to spread efficiently enough to cause a pandemic is limited, however, as transmission of these viruses requires close contact with the infected vector, and the vector only has a short time before death or serious illness. Furthermore, the short time between a vector becoming infectious and the onset of symptoms allows medical professionals to quickly quarantine vectors, and prevent them from carrying the pathogen elsewhere. Genetic mutations could occur, which could elevate their potential for causing widespread harm; thus close observation by contagious disease specialists is merited.

Antibiotic resistance

Antibiotic-resistant microorganisms, sometimes referred to as "superbugs", may contribute to the re-emergence of diseases which are currently well controlled.[110] For example, cases of tuberculosis that are resistant to traditionally effective treatments remain a cause of great concern to health professionals. Every year, nearly half a million new cases of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB) are estimated to occur worldwide.[111] China and India have the highest rate of multidrug-resistant TB.[112] The World Health Organization (WHO) reports that approximately 50 million people worldwide are infected with MDR TB, with 79 percent of those cases resistant to three or more antibiotics. In 2005, 124 cases of MDR TB were reported in the United States. Extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis (XDR TB) was identified in Africa in 2006, and subsequently discovered to exist in 49 countries, including the United States. There are about 40,000 new cases of XDR-TB per year, the WHO estimates.[113]

In the past 20 years, common bacteria including Staphylococcus aureus, Serratia marcescens and Enterococcus, have developed resistance to various antibiotics such as vancomycin, as well as whole classes of antibiotics, such as the aminoglycosides and cephalosporins. Antibiotic-resistant organisms have become an important cause of healthcare-associated (nosocomial) infections (HAI). In addition, infections caused by community-acquired strains of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in otherwise healthy individuals have become more frequent in recent years.

SARS

In 2003 the Italian physician Carlo Urbani (1956-2003) was the first to identify severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) as a new and dangerously contagious disease, although he became infected and died. It is caused by a coronavirus dubbed SARS-CoV. Rapid action by national and international health authorities such as the World Health Organization helped to slow transmission and eventually broke the chain of transmission, which ended the localized epidemics before they could become a pandemic. However, the disease has not been eradicated. It could re-emerge. This warrants monitoring and reporting of suspicious cases of atypical pneumonia.

Influenza

Wild aquatic birds are the natural hosts for a range of influenza A viruses. Occasionally, viruses are transmitted from these species to other species, and may then cause outbreaks in domestic poultry or, rarely, in humans.[114][115]

H5N1 (Avian Flu)

In February 2004, avian influenza virus was detected in birds in Vietnam, increasing fears of the emergence of new variant strains. It is feared that if the avian influenza virus combines with a human influenza virus (in a bird or a human), the new subtype created could be both highly contagious and highly lethal in humans. Such a subtype could cause a global influenza pandemic, similar to the Spanish Flu, or the lower mortality pandemics such as the Asian Flu and the Hong Kong Flu.

From October 2004 to February 2005, some 3,700 test kits of the 1957 Asian Flu virus were accidentally spread around the world from a lab in the US.[116]

In May 2005, scientists urgently called upon nations to prepare for a global influenza pandemic that could strike as much as 20% of the world's population.[117]

In October 2005, cases of the avian flu (the deadly strain H5N1) were identified in Turkey. EU Health Commissioner Markos Kyprianou said: "We have received now confirmation that the virus found in Turkey is an avian flu H5N1 virus. There is a direct relationship with viruses found in Russia, Mongolia and China." Cases of bird flu were also identified shortly thereafter in Romania, and then Greece. Possible cases of the virus have also been found in Croatia, Bulgaria and the United Kingdom.[118]

By November 2007, numerous confirmed cases of the H5N1 strain had been identified across Europe.[119] However, by the end of October, only 59 people had died as a result of H5N1, which was atypical of previous influenza pandemics.

Avian flu cannot yet be categorized as a "pandemic", because the virus cannot yet cause sustained and efficient human-to-human transmission. Cases so far are recognized to have been transmitted from bird to human, but as of December 2006, there have been very few (if any) cases of proven human-to-human transmission.[120] Regular influenza viruses establish infection by attaching to receptors in the throat and lungs, but the avian influenza virus can only attach to receptors located deep in the lungs of humans, requiring close, prolonged contact with infected patients, and thus limiting person-to-person transmission.

Zika virus

An outbreak of Zika virus began in 2015 and strongly intensified throughout the start of 2016, with over 1.5 million cases across more than a dozen countries in the Americas. The World Health Organisation warned that Zika had the potential to become an explosive global pandemic if the outbreak was not controlled.[121]

Economic consequences of pandemic events

In 2016 the Commission on a Global Health Risk Framework for the Future estimated that pandemic disease events would cost the global economy over $6 trillion in the 21st century - over $60 billion per year.[122] The same report also recommended spending $4.5 billion annually on global prevention and response capabilities to reduce the threat posed by pandemic events.

Biological warfare

In 1346, the bodies of Mongol warriors who had died of plague were thrown over the walls of the besieged Crimean city of Kaffa (now Theodosia). After a protracted siege, during which the Mongol army under Jani Beg was suffering the disease, they catapulted the infected corpses over the city walls to infect the inhabitants. It has been speculated that this operation may have been responsible for the arrival of the Black Death in Europe.[123]

The Native American population was devastated after contact with the Old World by introduction of many fatal diseases. In a well documented case of germ warfare involving British commander Jeffrey Amherst and Swiss-British officer Colonel Henry Bouquet, their correspondence included a proposal and agreement to give smallpox-infected blankets to Indians in order to "Extirpate this Execrable Race". During the siege of Fort Pitt late in the French and Indian War, as recorded in his journal by sundries trader and militia Captain, William Trent, on June 24, 1763, dignitaries from the Delaware tribe met with Fort Pitt officials, warned them of "great numbers of Indians" coming to attack the fort, and pleaded with them to leave the fort while there was still time. The commander of the fort refused to abandon the fort. Instead, the British gave as gifts two blankets, one silk handkerchief and one linen from the smallpox hospital to two Delaware Indian dignitaries.[124] A devastating smallpox epidemic plagued Native American tribes in the Ohio Valley and Great Lakes area through 1763 and 1764, but the effectiveness of individual instances of biological warfare remains unknown. After extensive review of surviving documentary evidence, historian Francis Jennings concluded the attempt at biological warfare was "unquestionably effective at Fort Pitt";[125] Smallpox after Pontiac's Rebellion killed 400,000–500,000 (possibly even up to 1.5 million) Native Americans.[126][127][128]

During the Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945), Unit 731 of the Imperial Japanese Army conducted human experimentation on thousands, mostly Chinese. In military campaigns, the Japanese army used biological weapons on Chinese soldiers and civilians. Plague fleas, infected clothing, and infected supplies encased in bombs were dropped on various targets. The resulting cholera, anthrax, and plague were estimated to have killed around 400,000 Chinese civilians.[129]

Diseases considered for or known to be used as a weapon include anthrax, ebola, Marburg virus, plague, cholera, typhus, Rocky Mountain spotted fever, tularemia, brucellosis, Q fever, machupo, Coccidioides mycosis, Glanders, Melioidosis, Shigella, Psittacosis, Japanese B encephalitis, Rift Valley fever, yellow fever, and smallpox.[130]

Spores of weaponized anthrax were accidentally released from a military facility near the Soviet closed city of Sverdlovsk in 1979. The Sverdlovsk anthrax leak is sometimes called "biological Chernobyl".[130] In January 2009, an Al-Qaeda training camp in Algeria was reportedly wiped out by the plague, killing approximately 40 Islamic extremists. Some experts said that the group was developing biological weapons,[131] however, a couple of days later the Algerian Health Ministry flatly denied this rumour stating "No case of plague of any type has been recorded in any region of Algeria since 2003".[132]

In popular culture

Literature

- The Decameron, a 14th-century writing by Italian author Giovanni Boccaccio, circa 1353

- The Last Man, a 1826 novel by Mary Shelley

- Pale Horse, Pale Rider, a 1939 short novel by Katherine Anne Porter

- The Plague, a 1947 novel by Albert Camus

- "The Secret Garden", a 1911 novel by Frances Hodgson Burnett

- Earth Abides, a 1949 novel by George R. Stewart

- I Am Legend, a 1954 science fiction/horror novel by American writer Richard Matheson

- The Andromeda Strain, a 1969 science fiction novel by Michael Crichton

- The Last Canadian, a 1974 novel by William C. Heine

- The Black Death, a 1977 novel by Gwyneth Cravens describing an outbreak of the Pneumonic plague in New York[133]

- The Stand, a 1978 novel by Stephen King

- And the Band Played On, a 1987 non-fiction account by Randy Shilts concerning the emergence and discovery of the HIV / AIDS pandemic

- The Last Town on Earth, a 2006 novel by Thomas Mullen

- World War Z, a 2006 novel by Max Brooks

- Company of Liars (2008), by Karen Maitland

- The Passage trilogy by Justin Cronin with The Passage (2010), The Twelve (2012), and The City of Mirrors due out in 2016

- The time-travel fiction of Connie Willis (such as Doomsday Book and To Say Nothing of the Dog), set in the mid-21st century and referencing a pandemic that occurred in the early part of the century

- Station Eleven, a 2014 novel by Emily St. John Mandel.

Film

- The Seventh Seal (1957), set during the black death

- The Last Man on Earth (1964), a horror/science fiction film based on the Richard Matheson novel I Am Legend

- The Omega Man (1971), an English science fiction film, based on the Richard Matheson novel I Am Legend

- Survivors (1975 TV series), a BBC TV series created by Terry Nation about a worldwide plague

- And the Band Played On (film) (1993), a HBO movie about the emergence of the HIV / AIDS pandemic; based on the 1987 novel by Randy Shilts

- The Stand (1994), based on the eponymous novel by Stephen King about a worldwide pandemic of biblical proportions

- The Horseman on the Roof (Le Hussard sur le Toit) (1995), a French film dealing with an 1832 cholera outbreak

- Twelve Monkeys (1995), set in a future world devastated by a man-made virus

- Outbreak (1995), fiction film focusing on an outbreak of an Ebola-like virus in Zaire and later in a small town in the United States

- Smallpox 2002 (2002), a fictional BBC docudrama

- 28 Days Later (2002), a fictional horror film following the outbreak of an infectious 'rage' virus that destroys all of mainland Britain

- End Day (2005), a fictional BBC docudrama

- I Am Legend (2007), a horror film starring Will Smith based on the Richard Matheson novel I Am Legend

- 28 Weeks Later (2007), the sequel film to 28 Days Later, ending with the evident spread of infection to mainland Europe

- Doomsday (2008), in which Scotland is quarantined following an epidemic

- After Armageddon (2010), fictional History Channel docudrama

- Contagion (2011), American thriller centering on the threat posed by a deadly disease and an international team of doctors contracted by the CDC to deal with the outbreak

- Halo: Pandemic (2009-2012), a popular Machinima web-series

- World War Z (2013), apocalyptic zombie film based on the 2006 novel of the same name by Max Brooks

Television

- Helix (2014-2015), a television series that depicts a team of scientists from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention who are tasked to prevent pandemics from occurring.

- 12 Monkeys (2015-), a television series that depicts James Cole, a time traveler, who travels from the year 2043 to the present day to stop the release of a deadly virus.

Games

- Pandemic (2008), a cooperative board game in which the players have to discover the cures for four diseases that break out at the same time.

- Plague Inc. (2012), a strategy game for smartphones and tablets by Ndemic Creations

- The Last of Us (2013), a post-apocalyptic survival game on PS3 by Naughty Dog.

- Tom Clancy's The Division (2015) A video game about a bioterrorist attack that has devastated the United States and thrown New York into anarchy.

See also

- Biological hazard

- Biological warfare

- Bioterrorism

- Bushmeat

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)

- Endemic

- Epidemic

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC)

- Globalization and disease

- Influenza pandemic

- Medieval demography

- Mortality from infectious diseases

- Pandemic Severity Index

- Public health emergency of international concern

- Risks to civilization, humans and planet Earth

- Super-spreader

- Syndemic

- Tropical diseases

- Timeline of global health

- WHO pandemic phases

References

Notes

- ↑ Miquel Porta (3 July 2008). Miquel Porta, ed. Dictionary of Epidemiology. Oxford University Press. p. 179. ISBN 978-0-19-531449-6. Retrieved 14 September 2012.

- ↑ "Current WHO phase of pandemic alert", World Health Organization 2009

- ↑ "WHO press conference on 2009 pandemic influenza" (PDF). World Health Organization. 26 May 2009. Retrieved 2010-08-26.

- ↑ "Pandemic influenza preparedness and response" (PDF). World Health Organization.

- ↑ WHO pandemic phase descriptions and main actions by phase Archived September 10, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "A whole industry is waiting for an epidemic". Der Spiegel. 21 July 2009. Retrieved 2010-08-26.

- ↑ Chong, Jia-Rui (October 30, 2007). "Analysis clarifies route of AIDS". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved July 6, 2014.

- ↑ "The South African Department of Health Study, 2006". Avert.org. Retrieved 2010-08-26.

- ↑ "Aids could kill 90 million Africans, says UN". London: Guardian. 2005-03-04. Retrieved 2010-08-26.

- ↑ "Ancient Athenian Plague Proves to Be Typhoid". Scientific American. January 25, 2006.

- ↑ Past pandemics that ravaged Europe. BBC News, November 7. 2005

- ↑ "Cambridge Catalogue page "Plague and the End of Antiquity"". Cambridge.org. Retrieved 2010-08-26.

- ↑ Quotes from book "Plague and the End of Antiquity" Lester K. Little, ed., Plague and the End of Antiquity: The Pandemic of 541–750, Cambridge, 2006. ISBN 0-521-84639-0

- ↑ "Plague, Plague Information, Black Death Facts, News, Photos". National Geographic. Retrieved 2008-11-03.

- ↑ New MOL Archaeology monograph: Black Death cemetery. Archaeology at the Museum of London.

- ↑ Death on a Grand Scale. MedHunters.

- ↑ Stéphane Barry and Norbert Gualde, in L'Histoire n° 310, June 2006, pp.45–46, say "between one-third and two-thirds"; Robert Gottfried (1983). "Black Death" in Dictionary of the Middle Ages, volume 2, pp.257–67, says "between 25 and 45 percent".

- ↑ Plague – LoveToKnow 1911. 1911encyclopedia.org.

- ↑ "A List of National Epidemics of Plague in England 1348–1665". Urbanrim.org.uk. 2010-08-04. Retrieved 2010-08-26.

- ↑ Jo Revill (May 16, 2004). "Black Death blamed on man, not rats | UK news | The Observer". London: The Observer. Retrieved 2008-11-03.

- ↑ "Texas Department of State Health Services, History of Plague". Dshs.state.tx.us. Retrieved 2008-11-03.

- ↑ Igeji, Mike. "Black Death". BBC. Retrieved 2008-11-03.

- ↑ The Great Plague of London, 1665. The Harvard University Library, Open Collections Program: Contagion.

- ↑ "Zoonotic Infections: Plague". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 20 April 2009. Retrieved 5 July 2014.

- ↑ Bubonic plague hits San Francisco 1900 – 1909. A Science Odyssey. Public Broadcasting Service (PBS).

- ↑ Human Plague – United States, 1993–1994, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- ↑ "Smallpox: Eradicating the Scourge". Bbc.co.uk. 2009-11-05. Retrieved 2010-08-26.

- ↑ Smallpox The Fight to Eradicate a Global Scourge, David A. Koplow

- ↑ Greg Lange,"Smallpox epidemic ravages Native Americans on the northwest coast of North America in the 1770s", 23 Jan 2003, HistoryLink.org, Online Encyclopedia of Washington State History, accessed 2 Jun 2008

- ↑ Houston CS, Houston S (March 2000). "The first smallpox epidemic on the Canadian Plains: In the fur-traders' words". Can J Infect Dis. 11 (2): 112–5. PMC 2094753

. PMID 18159275.

. PMID 18159275. - ↑ "The Story Of... Smallpox – and other Deadly Eurasian Germs". Pbs.org. Retrieved 2010-08-26.

- ↑ Stacy Goodling, "Effects of European Diseases on the Inhabitants of the New World" Archived May 10, 2008, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Smallpox Through History Archived October 29, 2009, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "New Zealand Historical Perspective". Canr.msu.edu. 1998-03-31. Archived from the original on June 12, 2010. Retrieved 2010-08-26.

- ↑ How did Easter Island's ancient statues lead to the destruction of an entire ecosystem?, The Independent

- ↑ Fiji School of Medicine Archived October 20, 2014, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Measles hits rare Andaman tribe. BBC News. May 16, 2006.

- ↑ Meeting the First Inhabitants, TIMEasia.com, 21 August 2000

- ↑ Genetic Study Bolsters Columbus Link to Syphilis, New York Times, January 15, 2008

- ↑ Columbus May Have Brought Syphilis to Europe, LiveScience

- ↑ Nomination VOC archives for Memory of the World Register (English)

- ↑ "Sahib: The British Soldier in India, 1750–1914 by Richard Holmes". Asianreviewofbooks.com. 2005-10-27. Retrieved 2010-08-26.

- ↑ Dr. Francisco de Balmis and his Mission of Mercy, Society of Philippine Health History Archived October 19, 2013, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Lewis Cass and the Politics of Disease: The Indian Vaccination Act of 1832". Muse.jhu.edu. Retrieved 2010-08-26.

- ↑ Conquest and Disease or Colonialism and Health?, Gresham College | Lectures and Events

- ↑ WHO Media centre (2001). "Fact sheet N°259: African trypanosomiasis or sleeping sickness".

- ↑ The Origins of African Population Growth, by John Iliffe, The Journal of African HistoryVol. 30, No. 1 (1989), pp. 165–169

- ↑ "World Population Clock – U.S. Census Bureau". U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved 2011-11-18.

- ↑ Kelley Lee (2003) "Health impacts of globalization: towards global governance". Palgrave Macmillan. p.131. ISBN 0-333-80254-3

- ↑ John Pike. "Cholera- Biological Weapons". Globalsecurity.org. Retrieved 2010-08-26.

- ↑ G. William Beardslee. "The 1832 Cholera Epidemic in New York State". Earlyamerica.com. Retrieved 2010-08-26.

- ↑ "Asiatic Cholera Pandemic of 1826–37". Ph.ucla.edu. Retrieved 2010-08-26.

- ↑ "The Cholera Epidemic Years in the United States". Tngenweb.org. Retrieved 2010-08-26.

- ↑ Cholera's seven pandemics, cbc.ca, December 2, 2008

- 1 2 The 1832 Cholera Epidemic in New York State – Page 2. By G. William Beardslee

- ↑ Kohn, George C. (2008). Encyclopedia of plague and pestilence: from ancient times to the present. Infobase Publishing. p. 369. ISBN 0-8160-6935-2.

- ↑ Byrne, Joseph Patrick (2008). Encyclopedia of Pestilence, Pandemics, and Plagues: A-M. ABC-CLIO. p. 101. ISBN 0-313-34102-8.

- ↑ "Eastern European Plagues and Epidemics 1300–1918". Shtetlinks.jewishgen.org. Retrieved 2010-08-26.

- ↑ "Cholera – LoveToKnow 1911". 1911encyclopedia.org. 2006-10-27. Retrieved 2010-08-26.

- ↑ "The cholera in Spain". New York Times. 1890-06-20. Retrieved 2008-12-08.

- ↑ Barry, John M. (2004). The Great Influenza: The Epic Story of the Greatest Plague in History. Viking Penguin. ISBN 0-670-89473-7.

- ↑ cholera :: Seven pandemics, Britannica Online Encyclopedia

- ↑ John M. Gates, Ch. 3, "The U.S. Army and Irregular Warfare"

- ↑ 50 Years of Influenza Surveillance. World Health Organization.

- ↑ "Pandemic Flu". Department of Health and Social Security. Archived January 7, 2012, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Beveridge, W.I.B. (1977) Influenza: The Last Great Plague: An Unfinished Story of Discovery, New York: Prodist. ISBN 0-88202-118-4.

- ↑ Potter, C.W. (October 2001). "A History of Influenza". Journal of Applied Microbiology. 91 (4): 572–579. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2672.2001.01492.x. PMID 11576290. Retrieved 2006-08-20.

- ↑ CIDRAP article Pandemic Influenza Last updated 16 June 2011

- 1 2 Taubenberger JK, Morens DM (January 2006). "1918 Influenza: the mother of all pandemics". Emerg Infect Dis. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 12 (1): 15–22. doi:10.3201/eid1201.050979. PMC 3291398

. PMID 16494711.

. PMID 16494711. - ↑ Spanish flu, ScienceDaily

- ↑ The Great Pandemic: The United States in 1918–1919, U.S. Department of Health & Human Services.

- ↑ http://www.scientificamerican.com/blog/post.cfm?id=h1n1-shares-key-similar-structures-2010-03-24

- ↑ Q&A: Swine flu. BBC News. April 27, 2009.

- ↑ War and Pestilence. TIME. April 29, 1940

- ↑ The Historical Impact of Epidemic Typhus. Joseph M. Conlon.

- ↑ War and Pestilence. TIME.

- 1 2 Joseph M. Conlon. "The historical impact of epidemic typhus" (PDF). Retrieved 2009-04-21.

- ↑ Soviet Prisoners of War: Forgotten Nazi Victims of World War II By Jonathan Nor, TheHistoryNet

- ↑ Smallpox and Vaccinia. National Center for Biotechnology Information.

- ↑ "UC Davis Magazine, Summer 2006: Epidemics on the Horizon". Archived from the original on December 11, 2008. Retrieved 2008-01-03.

- ↑ How Poxviruses Such As Smallpox Evade The Immune System, ScienceDaily, February 1, 2008

- ↑ "Smallpox". WHO Factsheet. Retrieved on 2007-09-22.

- ↑ De Cock KM (2001). "(Book Review) The Eradication of Smallpox: Edward Jenner and The First and Only Eradication of a Human Infectious Disease". Nature Medicine. 7 (1): 15–6. doi:10.1038/83283.

- ↑ {http://www.oie.int/en/for-the-media/rinderpest/. 2 April 2014. World Organization for Animal Health}

- ↑ Center for Disease Control & National Immunization Program. Measles History, article online 2001. Available from http://www.cdc.gov.nip/diseases/measles/history.htm

- 1 2 "Torrey EF and Yolken RH. 2005. Their bugs are worse than their bite. Washington Post, April 3, p. B01". Birdflubook.com. Retrieved 2010-08-26.

- ↑ Stein CE, Birmingham M, Kurian M, Duclos P, Strebel P (May 2003). "The global burden of measles in the year 2000—a model that uses country-specific indicators". J. Infect. Dis. 187 (Suppl 1): S8–14. doi:10.1086/368114. PMID 12721886.

- ↑ Man and Microbes: Disease and Plagues in History and Modern Times; by Arno Karlen

- ↑ "Measles and Small Pox as an Allied Army of the Conquistadors of America" by Carlos Ruvalcaba, translated by Theresa M. Betz in "Encounters" (Double Issue No. 5-6, pp. 44–45)

- ↑ World Health Organization (WHO). Tuberculosis Fact sheet N°104 – Global and regional incidence. March 2006, Retrieved on 6 October 2006.

- ↑ Centers for Disease Control. Fact Sheet: Tuberculosis in the United States. 17 March 2005, Retrieved on 6 October 2006.

- ↑ Multidrug-Resistant Tuberculosis. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

- ↑ Immune responses to tuberculosis in developing countries: implications for new vaccines. Nature Reviews Immunology 5, 661–667 (August 2005).

- ↑ Leprosy 'could pose new threat'. BBC News. April 3, 2007.

- ↑ "Leprosy". WHO. Retrieved 2007-08-22.

- ↑ "Medieval leprosy reconsidered". International Social Science Review, Spring-Summer, 2006, by Timothy S. Miller, Rachel Smith-Savage.

- ↑ Boldsen JL (February 2005). "Leprosy and mortality in the Medieval Danish village of Tirup". Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 126 (2): 159–68. doi:10.1002/ajpa.20085. PMID 15386293.

- ↑

Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Leprosy". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Leprosy". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. - ↑ Malaria Facts. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

- ↑ White NJ (April 2004). "Antimalarial drug resistance". J. Clin. Invest. 113 (8): 1084–92. doi:10.1172/JCI21682. PMC 385418

. PMID 15085184.

. PMID 15085184. - ↑ Vector- and Rodent-Borne Diseases in Europe and North America. Norman G. Gratz. World Health Organization, Geneva.

- ↑ DNA clues to malaria in ancient Rome. BBC News. February 20, 2001.

- ↑ "Malaria and Rome". Robert Sallares. ABC.net.au. January 29, 2003.

- ↑ "The Changing World of Pacific Northwest Indians". Center for the Study of the Pacific Northwest, University of Washington.

- ↑ "A Brief History of Malaria". Infoplease.com. Retrieved 2010-08-26.

- ↑ Malaria. By Michael Finkel. National Geographic Magazine.

- ↑ Yellow Fever – LoveToKnow 1911.

- ↑ Arnebeck, Bob (January 30, 2008). "A Short History of Yellow Fever in the US". Benjamin Rush, Yellow Fever and the Birth of Modern Medicine. Archived from the original on 2007-11-07. Retrieved 2008-12-04.

- ↑ Africa's Nations Start to Be TheirBrothers' Keepers. The New York Times, October 15, 1995.

- ↑ Researchers sound the alarm: the multidrug resistance of the plague bacillus could spread. Pasteur.fr

- ↑ Health ministers to accelerate efforts against drug-resistant TB. World Health Organization.

- ↑ Bill Gates joins Chinese government in tackling TB 'timebomb'. Guardian.co.uk. April 1, 2009

- ↑ Tuberculosis: A new pandemic?. CNN.com

- ↑ Klenk; et al. (2008). "Avian Influenza: Molecular Mechanisms of Pathogenesis and Host Range". Animal Viruses: Molecular Biology. Caister Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-904455-22-6.

- ↑ Kawaoka Y (editor). (2006). Influenza Virology: Current Topics. Caister Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-904455-06-6.

- ↑ MacKenzie D (13 April 2005). "Pandemic-causing 'Asian flu' accidentally released". New Scientist.

- ↑ "Flu pandemic 'could hit 20% of world's population'". London: guardian.co.uk. 25 May 2005. Retrieved May 21, 2010.

- ↑ "Bird flu is confirmed in Greece". BBC NEWS. 17 October 2005. Retrieved 2010-01-03.

- ↑ "Bird Flu Map". BBC NEWS. Retrieved 2010-01-03.

- ↑ WHO (2005). Avian Influenza A (H5N1) Infection in Humans http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMra052211

- ↑ http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-us-canada-35425731

- ↑ "Global Health Risk Framework - The Neglected Dimension of Global Security: A Framework to Counter Infectious Disease Crises" (PDF). National Academy of Medicine. 2016-01-16. Retrieved 2016-08-02.

- ↑ Wheelis M (September 2002). "Biological Warfare at the 1346 Siege of Caffa". Emerging Infect. Dis. 8 (9): 971–5. doi:10.3201/eid0809.010536. PMC 2732530

. PMID 12194776.

. PMID 12194776. - ↑ Fenn, Elizabeth A. Biological Warfare in Eighteenth-Century North America: Beyond Jeffery Amherst; The Journal of American History, Vol. 86, No. 4, March, 2000

- ↑ Empire of Fortune; Francis Jennings; W. W. Norton & Company; 1988; Pgs. 447-8

- ↑ Crawford, Native Americans of the Pontiac's War, 245–250

- ↑ Phillip M. White (June 2, 2011). American Indian Chronology: Chronologies of the American Mosaic. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 44.

- ↑ D. Hank Ellison (August 24, 2007). Handbook of Chemical and Biological Warfare Agents. CRC Press. pp. 123–140. ISBN 0-8493-1434-8.

- ↑ Christopher Hudson (2 March 2007). "Doctors of Depravity". London: Daily Mail.

- 1 2 Ken Alibek and S. Handelman. Biohazard: The Chilling True Story of the Largest Covert Biological Weapons Program in the World – Told from Inside by the Man Who Ran it. 1999. Delta (2000) ISBN 0-385-33496-6 .

- ↑ Al-Qaeda cell killed by Black Death 'was developing biological weapons' Telegraph. January 20, 2009.

- ↑ Plague outbreak denied Feb. 5, 2009.

- ↑ http://www.paperbackswap.com/Black-Death-Gwyneth-Cravens/book/0345271556/

Further reading

- American Lung Association. (2007, April), Multidrug Resistant Tuberculosis Fact Sheet. As retrieved from www.lungusa.org/site/pp.aspx?c=dvLUK9O0E&b=35815 November 29, 2007.

- Larson E (2007). "Community factors in the development of antibiotic resistance". Annu Rev Public Health. 28: 435–47. doi:10.1146/annurev.publhealth.28.021406.144020. PMID 17094768.

- Bancroft EA (October 2007). "Antimicrobial resistance: it's not just for hospitals". JAMA. 298 (15): 1803–4. doi:10.1001/jama.298.15.1803. PMID 17940239.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pandemic. |

- WHO – Authoritative source of information about global health issues

- Past pandemics that ravaged Europe

- CDC: Influenza Pandemic Phases

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control – ECDC

- The American Journal of Bioethics' ethical issues in pandemics page

- TED-Education video – How pandemics spread.