Vladimir Rosing

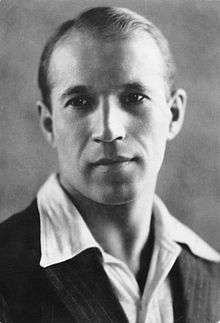

Vladimir Sergeyevich Rosing (Russian: Владимир Серге́евич Розинг) (January 23 [O.S. January 11] 1890 – November 24, 1963), aka Val Rosing, was a Russian-born operatic tenor and stage director who spent most of his professional career in England and the United States. In his formative years he experienced the last years of the "golden age" of opera, and he dedicated himself through his singing and directing into breathing new life into opera's outworn mannerisms and methods.

Rosing was considered by many to rank as a singer and performer of the quality of Feodor Chaliapin.[1] In The Perfect Wagnerite, George Bernard Shaw called Chaliapin and Vladimir Rosing "the two most extraordinary singers of the 20th century."[2]

Vladimir Rosing's best known recordings are his performances of Russian art songs by composers such as Modest Mussorgsky, Nikolai Tcherepnin, Alexander Gretchaninov, Alexander Borodin and Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov. He was the first singer to record a song by Igor Stravinsky: Akahito from Three Japanese Songs.[3]

As a stage director, Rosing championed opera in English, and he attempted to build permanent national opera companies in the United States and England. He directed opera performances "with such acumen and freshness of approach that some writers were tempted to speak of him as a second Reinhardt."[4]

Rosing created his own system of stage movement and acting for singers. It proved very effective in his own productions and he taught it to a new generation of performers.[5]

Early life

Rosing was born into an aristocratic family in St. Petersburg, Russia, on January 23, 1890. His father was descended from a Swedish officer captured by Russian forces at the Battle of Poltava. His mother was the granddaughter of a Baltic Baron.[6]

Rosing's parents separated when he was three, and his mother took Vladimir and his two older sisters to live in Switzerland. After four years they returned to Russia to live in Moscow near Rosing's godfather, General Arkady Stolypin, who was Commandant of the Kremlin and father of Russian Prime Minister Pyotr Stolypin. For a time they lived in the Poteshny Palace at the Kremlin as General Stolypin's guests.[7]

Rosing spent the summer of 1898 on his godfather's country estate south of Moscow near Tula. He traveled with his mother to meet Leo Tolstoy as his nearby estate, Yasnaya Polyana. At Tolstoy's request, Rosing's mother carried a message meant for the Tsar to General Stolypin, who later declined to deliver it.[8][9]

When Tsar Nicholas II visited Moscow, Vladimir and his family attended a performance of Tchaikovsky's opera Eugene Onegin, with the baritone Mattia Battistini, at the Bolshoi Theatre. They sat in General Stolypin's box just a few feet away from the Royal Box occupied by the Tsar and his family.[10]

Rosing's parents reconciled the next year, and the family moved back to St. Petersburg. Rosing completed his studies at the Gymnasium (school) which lasted for eight years in Russia, and the family spent summers on their country estate in Podolia, Ukraine.[11]

Russia was one of the biggest early markets for recorded music. Rosing's father brought home a gramophone in 1901, and Vladimir began to listen to and imitate the great singers of the day. He learned a repertoire of songs and arias, singing baritone as well as tenor parts.[12] His real desire was to be a bass and sing Boito's Mefistofele.[13]

In 1905, Rosing witnessed the massacre in front of the Winter Palace on Bloody Sunday. He then ceased being a monarchist and allied himself with the Constitutional Democratic Party. To please his father, a successful lawyer, Rosing reluctantly studied law at Saint Petersburg University, where he was very active in the fiery student politics that followed the first Russian Revolution of 1905. He sparred in heated debates with future Bolshevik commissar Nikolai Krylenko. He acted as a student deputy to the Saint Petersburg Soviet where he heard speeches by Leon Trotsky and others. Rosing soon developed a lifelong animosity towards the Bolsheviks.[14]

Aside from politics, he focused on music and theatre. When his parents finally accepted the primacy of his musical interests, he began to study voice with Mariya Slavina, Alexandra Kartseva, and Joachim Tartakov.[15]

In 1908 Rosing fell in love with an English musician, Marie Falle, whom he met while on holiday in Switzerland.[16] They married in London in February 1909. He studied voice in London with Sir George Power, before returning to Russia to finish law school.[nb 1]

Recital career and politics

After spending the 1912 season in St. Petersburg as an up-and-coming tenor with Joseph Lapitsky's innovative Theatre of Musical Drama, Vladimir Rosing made his London concert debut in Albert Hall on May 25, 1913. He spent the summer in Paris studying with Jean de Reszke and Giovanni Sbriglia. Sbriglia finally gave Rosing the technique and direction he needed to set aside thoughts of a career in law forever.[18][nb 2]

From 1912 to 1916 Rosing released 16 discs on the HMV label, many of which were recorded by the pioneering American record producer Fred Gaisberg in St. Petersburg and London.[20]

In 1914 he signed a 6-year contract with impresario Hans Gregor to perform leading tenor roles at the Vienna Imperial Opera, but World War I broke out before the fall season started, and Rosing returned to London.[21]

London's appetite for Russians and Russian music was high after Serge Diaghilev's historic seasons of Russian opera and ballet, and Rosing's recitals in England soon became extremely popular.[22] In addition to his public recitals, Rosing was in demand as a performer for London society's exclusive "At Homes", where he became friendly with rich, famous and powerful people like C. P. Scott, David Lloyd George, Lord Reading, Alfred Mond, and Prime Minister H. H. Asquith and his wife Margot.[23]

Rosing also socialized with writers like Ezra Pound, George Bernard Shaw, Hugh Walpole and Arnold Bennett, and his circle included the artists Glyn Philpot, Augustus John, Walter Sickert and Charles Ricketts.[24] [nb 3]

Rosing's ambition was to have his own opera company. In May 1915 he produced a brief Allied Opera Season at Oscar Hammerstein I's vacant London Opera House. Rosing presented the English premiere of Tchaikovsky's The Queen of Spades and introduced Tamaki Miura in Madama Butterfly, the first Japanese singer to be cast in that opera's title role. The season was brought to an early close when London was targeted by zeppelin raids for the first time in the war.[26]

Rosing returned to Russia for two months in the summer of 1915 after the Tsar called up the 2nd Reserves. As an only son, he was officially assigned to the Serbian Red Cross and he returned to London to organize benefit concerts. He was later awarded the Serbian Order of St. Sava Fifth Class for his service.[27]

When the Russian Revolution broke out in March 1917, Rosing went to see Lloyd George to urge him to support the new Provisional Government.[28] He headed up the newly formed Committee for Repatriation of Political Exiles. A few months later, when Georgy Chicherin was imprisoned by the British, Rosing met again with Lloyd George to seek Chicherin's release.[29][nb 4]

As a result of the Bolsheviks' seizure of power, Rosing was one of many Russians to lose his wealth. As Russian refugees poured into London, Rosing was at the center of the action. He socialized with Prince Felix Yusupov, organizer of the murder of Rasputin, and Alexander Kerensky, Prime Minister of the failed Russian Provisional Government.[31][32]

Rosing's recitals were more popular than ever. In the fall of 1919 he joined soprano Emma Calvé and pianist Arthur Rubinstein for a concert tour of the English Provinces.[33] He filled in for John McCormack in Belfast, winning acclaim from the Irish.[34] On March 6, 1921 in Albert Hall he gave his 100th London recital.[35]

Rosing recorded 61 discs for Vocalion Records in the early 1920s.[36]

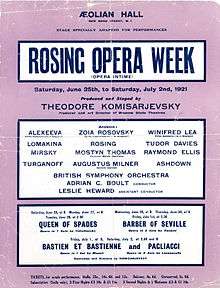

In June 1921 he presented, with director Theodore Komisarjevsky and conductor Adrian Boult, a season of Opera Intime at London's Aeolian Hall.[37] At Rosing's invitation, Isadora Duncan attended one of the performances.[38] The Opera Intime company then toured Glasgow and Edinburgh.

Rosing left England for his first concert tour of the United States and Canada in November 1921. The tour generated an invitation to sing at a White House State Dinner held by President Harding on February 2, 1922.[39] With his friends, writer William C. Bullitt and sculptress Clare Sheridan, Rosing organized the last concert of the tour in New York on March 10, 1922, as a benefit for Herbert Hoover's American Relief Administration, raising money to help fight the terrible famine in Russia.[40][nb 5]

Rosing returned for his second tour of the United States and Canada in November 1922. On the voyage back to England in March 1923 he met a representative of Kodak's George Eastman, which led to an offer a few weeks later to return to the United States to start the opera department at the newly opened Eastman School of Music in Rochester. Rosing saw a chance to create the opera company he had always wanted, and he jumped at the opportunity to sell Eastman on his dream.[42][nb 6]

Theory of movement

By the time Vladimir Rosing went to Rochester, he had already started to develop his own theories of movement and stage direction. The breakthrough had come by spending weeks studying the great statues in the Louvre. Rosing analyzed what made them beautiful, graceful or convey emotion and figured out how to transfer that expressive power to physical bodies in movement on a stage. When he spoke of sculpting body movement he was literally bringing great sculptures to life through a set of rules and techniques he had worked out.[44]

Rosing's central idea was that there is a definite time, place and reason for the beginning of a gesture and a definite time to retrieve it—and that all gestures must be retrieved. He taught rules for the independent and coordinated action of the joints used in sculpting body movement, that every movement has a preparatory movement in the opposite direction, and that the retreat of a gesture is of extreme importance.

Rosing taught eye focus and head angles. He did away with waving arms and wandering hands and he demanded that every unnecessary movement be eliminated. His staging formula was to move and hold, as though a series of still shots was being photographed, or sculptures animated.

Rosing did not set patterns of stage action to music. He believed opera could achieve its maximum effectiveness with dramatic interpretation resulting from rather than affixing itself to the music. The body and music should become as one—a complete blend of sound and motion, with every motion coming out of the sound.

Rosing built his entire principle of stage action on this theory. It was a choreographic approach, but unlike ballet which is mathematical and its motion continuous, the resulting style was completely different.[45]

In Rochester, Rosing had the chance to test and refine his theories for the next seven years.

American Opera Company

With George Eastman's backing, Rosing envisioned professionally training a group of young American singers and turning them into a national repertory company, performing opera across the United States in easy-to-understand English translations. He did that with the help of enthusiastic artists and benefactors.

The group of artists that came to work with Rosing in Rochester included Eugene Goossens, Albert Coates, Rouben Mamoulian, Nicolas Slonimsky, Otto Luening, Ernst Bacon, Emanuel Balaban, Paul Horgan, Anna Duncan, and Martha Graham.[46] An initial group of 20 singers was chosen from across the United States and given full scholarships.[47]

Even though a transition to a new career as a director had begun, Rosing made another recital tour of Canada,[48] gave concerts with the Rochester Philharmonic, and on October 20, 1924, presented a concert at Carnegie Hall with Nicolas Slonimsky as his accompanist.[49]

In November 1924, after a year of gestation and training, the Rochester American Opera Company was announced.[50] It made a tour of Western Canada in January 1926. Performances in Rochester and Chautauqua followed. Mary Garden was so impressed with the group that she came to sing Carmen with the company in February 1927 at the Eastman School's intimate Kilbourn Hall.[51] Later that month, Vladimir married his second wife, soprano Margaret Williamson, who was a member of the company.

The opera company strictly adhered to a non-star policy, developing instead a unity of ensemble whereby a singer might have a leading role one night and a supporting role the next.[52]

At the invitation of the Theatre Guild, the Rochester American Opera Company made its New York debut in April 1927, giving a full week of performances at the Guild Theatre with Eugene Goossens conducting.[53]

A committee of wealthy and influential backers was formed to help take the company to the next level.[54] Summer 1927 was spent rehearsing in Magnolia, Massachusetts, for the fall season and performing at Leslie Buswell's private theater at his nearby mansion, Stillington Hall.[55] In December 1927, the newly christened American Opera Company performed for President and Mrs. Coolidge and 150 members of Congress at Washington D.C.'s Poli's Theater.

During January and February 1928, the American Opera Company brought seven weeks of opera to Broadway at New York's Gallo Theater. Robert Edmond Jones contributed set designs.[56]

National tours followed for the next two years, but the stock market crash of 1929 caused bookings for the 1930 season to dematerialize. The group earned an official endorsement from President Herbert Hoover, who called for it to become "a permanent national institution",[57] but as the country sank into the Great Depression the company was forced to disband.

Pulitzer Prize–winning author Paul Horgan's first novel, The Fault of Angels, published in 1933, is a fictionalized account of the early days of the Eastman School's opera department.[58]

Aside from directing a few plays, the early 1930s were lean times for Rosing. He had become an American citizen in 1930, but when an offer came from the BBC for a broadcast performance he returned to London.[59]

First televised opera

Rosing remained popular as a recitalist in England, and he resumed giving concerts there upon his return in 1933.[60] Rosing signed a new contract with the Parlophone Company and recorded 32 discs (with the new electrical method) between 1933 and 1937.[61]

A musical production of Richard Brinsley Sheridan's The Rivals with songs by Herbert Hughes and John Robert Monsell was staged at the Kingsway Theatre in September 1935. Queen Mary attended one of the performances.[62]

On November 2, 1936, the BBC began the world's first regularly scheduled television service. Less than two weeks later, on November 13, The British Music Drama Opera Company under the Rosing's direction presented the world's first televised opera, Pickwick by Albert Coates. The performance was a preview of the new company's upcoming season at the Royal Opera House at Covent Garden.[63]

The Covent Garden season opened on November 18, 1936, with Boris Godunov. Madama Butterfly, The Fair at Sorochyntsi, and Pagliacci followed, along with the premier of Coates' Pickwick and another new opera, Julia, by Roger Quilter.[64]

On October 5, 1938, Rosing was back at the BBC for a live television broadcast of Pagliacci with his latest opera venture, the Covent Garden English Opera Company.[65] Again, it was a preview of the upcoming season which opened with Faust on October 10, with Eugene Goossens conducting. Along with Rigoletto, Madama Butterfly, Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg, Pagliacci and Cavalleria rusticana was an unfamiliar work, The Serf, by George Lloyd. After the London season, the company toured Liverpool, Glasgow and Edinburgh.[66]

Return to America

World War II

When war broke out again in Europe in September 1939, Rosing went with his friend Albert Coates to Southern California. Rosing married his third wife, the English actress Vicki Campbell, and they boarded the SS Washington in Southampton on October 3, 1939. The ship was overflowing with artists fleeing Europe, including Arturo Toscanini, Arthur Rubinstein, Paul Robeson, and the Russian Ballet.[67]

Once safely in Hollywood, Rosing and Coates formed the Southern California Opera Association. In conjunction with the Works Progress Administration, they produced a notable production of Faust that featured the debut of soprano Nadine Conner.

Rosing renewed his political activities, becoming Executive Chairman of the Federal Union of Southern California, a new group whose members included Thomas Mann, John Carradine, Douglas Fairbanks Jr., and Melvyn Douglas. The group worked to counter American isolationist sentiment and support aid for England war efforts.[68]

When the United States joined the war, Rosing wanted to be of service. He was appointed Director of Entertainment at Camp Roberts, California, in 1943. The film studios lent their stable of stars, and with the help of talented servicemen Rosing directed over 20 productions of musical theater and light opera for the troops.[69] His last production at Camp Roberts was a staged version of Handel's Messiah in December 1945.[70]

Along with Capt. Hugh Edwards, another Camp Roberts veteran, Rosing founded the American Operatic Laboratory in 1946. The idea was to offer complete vocal and instrumental courses to music students, as well as returning soldiers on the GI bill. The school started with 17 students, and over the next three years 450 pupils were trained, most of whom were veterans. Over 300 performances were given of 33 different opera productions.[71] One of Rosing's young students, Jean Hillard, eventually became his fourth wife.

Rosing worked locally with the Long Beach Civic Opera Association on productions of The Merry Widow, Naughty Marietta, and Rio Rita in 1946. Under the banner of the American Opera Company of Los Angeles, he directed Tosca, The Barber of Seville, and Faust in 1947 with an up-and-coming young bass named Jerome Hines. In 1948 the National Opera Association of Los Angeles, under his direction, presented The Beggar's Opera, The Abduction from the Seraglio, Pagliacci, Rigoletto, Faust, and La traviata with soprano Jean Fenn. Productions of The Marriage of Figaro, The Queen of Spades, and Don Giovanni with the American Opera Company of Los Angeles completed 1948.

For KFI-TV in 1949 Rosing presented 46 weeks of live televised opera sequences on Sunday afternoons which were voted Outstanding Musical Program of Local Origin by the Southern California Association for Better Radio and T.V.[72]

New York City Opera

In the fall of 1949 an offer came from the New York City Opera (NYCO) to revive Prokofiev's comic opera The Love for Three Oranges. Rosing's old friend Theodore Komisarjevsky had been slated to direct the production but had suffered a heart attack. Vladimir had seen the original failed production commissioned by the Chicago Opera in 1921, and he knew what the work needed to bring it to success. His production opened in November 1949 and was a smash hit. Life Magazine covered it with a three-page color-photo spread.[73] The New York company took the production to Chicago. Prokofiev's opera was brought back by popular demand for two more successive seasons in New York.

Over the next decade Rosing directed ten more productions for the NYCO, including Douglas Moore's The Ballad of Baby Doe which ran for two seasons in 1958 and featured the role debut of soprano Beverly Sills.[74] The production was revived again in 1962.

Opera in films

Rosing directed opera sequences for four films during this period, starting with Everybody Does It starring Linda Darnell for 20th Century Fox in 1949. Grounds for Marriage with Kathryn Grayson followed for MGM in 1950. Rosing directed Ezio Pinza in Strictly Dishonorable, and Interrupted Melody with Eleanor Parker in 1955, also both for MGM.[75]

Hollywood Bowl

In 1950, as California was celebrating one hundred years of statehood, Rosing directed a new production of Faust with Nadine Conner, Jerome Hines and Richard Tucker, which opened the Hollywood Bowl's summer season.[76] Rosing's work was noticed by the producers of the upcoming The California Story, the official state centennial production to be mounted in the Bowl that fall, and he was asked to direct it. Meredith Willson supervised the music.[77] The California Story ran for five performances in September 1950. A chorus of 200 and hundreds of actors were employed. The shell of the bowl was removed and the stage was enlarged. The action was expanded to include the surrounding hillsides. Lionel Barrymore provided the dramatic narration.[78]

The California Story's success opened a new avenue for Rosing: the historical spectacular, The Air Power Pageant in the Bowl in 1951 and The Elks Story in 1954. In 1956 Rosing directed a similarly lavish production of The California Story in San Diego as the main production of a newly created civic festival, Fiesta del Pacifico.[79]

Rosing also directed three more operas at the Bowl: Die Fledermaus[nb 7] in 1951, Madama Butterfly with Dorothy Kirsten in 1960, and The Student Prince with Igor Gorin in 1962.

Lyric Opera of Chicago

Starting in 1955 with Il tabarro, Vladimir Rosing directed a dozen productions over the next seven years for the Lyric Opera of Chicago, including Boris Godunov with Boris Christoff, Turandot with Birgit Nilsson in 1958, and Thaïs with Leontyne Price in 1959. Rosing's last opera there, in 1962, was Borodin's Prince Igor, also with Boris Christoff—a production that featured sets by Nicola Benois, choreography by Ruth Page and dancing by Rudolf Nureyev, newly arrived in the West from Russia.[84]

Opera Guild of Montreal

The Opera Guild of Montreal, founded by soprano Pauline Donalda, brought Rosing to direct Verdi's Falstaff in January 1958 at Her Majesty's Theatre. Through 1962, Rosing directed a production each January for the Guild: Macbeth (1959), Carmen (1960), Romeo et Juliette (1961) and La traviata (1962). The renowned Russian conductor Emil Cooper led the orchestra for the first three seasons.[85]

Centennials

The success of The California Story at the Hollywood Bowl in 1950 led to the show's revival in similarly grand fashion for San Diego's annual Fiesta del Pacifico in 1956, 1957, and 1958.[86] Other states took notice, and Rosing was hired to write and direct centennial productions for Oregon in 1959,[87] Kansas in 1961,[88] and Arizona in 1963.[89] He was assisted by his fifth wife, Ruth Scates, whom he married in 1959.

The Freedom Story

Rosing conceived of a spectacular production, The Civil War Story, that would be funded jointly by participating States and tour the country for several years to mark the war's centennial. Rosing planned to produce, write and direct the production. After a disappointing failure to win bi-partisan support in the Northern and Southern states for this ambitious project, Rosing then conceived of an even bigger production that would instead tell the story of freedom itself. The Freedom Story would be an ambassador of freedom and peace, sent from America to the rest of the world, performing in local languages. Rosing wanted to use the power of art to fight the forces of totalitarianism that he saw threatening America's freedom. The project won wide support, with an Advisory Board that included Alf Landon, Harry S. Truman, and Dwight D. Eisenhower. Meredith Willson had agreed to create the music.[90]

While working on the Arizona Story, Rosing contracted septicemia.[91] He died in Santa Monica on November 24, 1963.[92]

Recordings

Vladimir Rosing's complete discography was published in The Record Collector (Vol. 36 No. 3, July, August, September 1991). All the original recordings were issued as 78 RPM records on HMV, Vocalion and Parlophone, but a number have been re-released on LP and CD.

78

- From 1912-1916 Rosing recorded 16 discs for the HMV label.

- In the 1920s Rosing recorded 61 discs for the Vocalion Company in England and America.

- In the mid-1930s, after returning to England, Rosing recorded his last 32 discs for the Parlophone Company.

- Three previously unreleased recordings in the EMI vault were discovered and issued to collectors by Historic Masters on HM 161 and HM 199b.

LP

- In 1952, American Decca released an LP album, Fourteen Songs of Mussorgsky (DL 9577) taken from Rosing's Parlophone recordings made in April 1935.

- TAP Records selected Vladimir Rosing for its Twenty Great Russian Singers of the Twentieth Century (T 320) released in 1959.

- Rosing was next included in Volume 3 of EMI's massive The Record of Singing in 1984 (EX 290169 3), re-released on CD in 1999 by Testament (SBT 0132).

- Not forgotten in his birth country, the Soviet record label Melodiya released a comprehensive 3-record set in the 1980s on their Musical Heritage Series (M10 46417 003, M10 46475 007, & M10 48083 006).

- "The Songs of Moussorgsky" (another reissue of the 1930s Parlophone recordings) was released in Japan by Artisco Records (YD-3014).

CD or MP3

- In 1993 Pearl Records released a CD collection, Russian Art Song (GEMM 9021), pairing the 1930s recordings of Vladimir Rosing and Oda Slobodskaya.

- Stars of David - Music by Singers of Jewish Heritage - Audio Encyclopedia AE 002. Rosing's inclusion on this CD set is a stretch. Rosing's mother was half Jewish—but his upbringing was completely Russian Orthodox.

- Treasures of the St. Petersburg State Museum (NI 7915/6), a double-CD released by Nimbus Records in 2004, featured two of Rosing's recordings.

- Naxos Records included three of Rosing's recordings on the 2006 Naxos Historical CD release of Mussorgsky: Khovanschina (NAXOS 8.111124-26).

- Anthology of Russian Romance: Tenors in the Russian Vocal Tradition includes four tracks by Rosing. 2008 Music Online.

- Vocal Record Collectors' Society - 2009 Issue (VRCS 2009/2), CD distributed by Norbeck, Peters & Ford (V1660), includes one Rosing track.

- Male Singers 4: The Definitive Collection Of The 19th Century's Greatest Virtuosos (pre-1940 Vintage Record) includes eight Rosing recordings (RMR 2010).

- The Stars of the Soviet Opera Houses - Tenors - Volume 8 PA-1103 from Papillon (released by opera-club.net) contains six Rosing performances.

- Rosing's performance of Massenet's Élégie with violinist Albert Sammon's is featured on the CD London String Quartet Volume VI (St. Laurent YSL 78-237).

Marriages

- Marie Falle; married 1909; divorced 1926; son, Valerian,[nb 8] born 1910.

- Margaret (Peggy) Williamson; married 1927; divorced 1931; daughter, Diana, born 1928.

- Winifred (Vicki) Campbell; married 1939; divorced 1951.

- Virginia (Jean) Hillard; married 1952; divorced 1959; son, Richard, born 1955.

- Ruth Scates, married 1959.

Writing

During the Cold War, Rosing channeled his political energies into writing a novel as well as a series of scripts about Russia for stage and television.

- The House of Rosanoff, a novel set in the years leading up to the Russian Revolution, all the way through World War II.

- The Crown Changes Hands, a play about class struggle during the Russian Revolution, produced twice in Los Angeles (1948 and 1953).

- Lenin, a biographical play, written in the 1950s.

- Stalin, a biographical television script, written in the late 1950s.

Quotes

"I look upon music and art from a very idealistic standpoint. To me, music is closely connected with the whole evolutionary process, the progress of the human race, the fundamental question of being—of life—of God.

What is perfection in art we, with our finite minds, cannot yet grasp. What seems wonderful and perfect to us now, probably will seem childish in a few hundred years. What seems impossible now will be possible then.

I do hope the time will soon arrive when the masses will awaken themselves to the realization of the great mission of art in life, and will cease to consider it as an amusement, hobby, recreation, snobbism; when governments will cease to be blind and will take art under their special care, will help to develop it as one of the great national treasures and assets, as the great factor for education of the mind, and will give broadly this spiritual food of mankind to the masses. It is time they should understand that it is one of their principal factors (if they are honest) to further the evolution of civilization."

Rosing, Vladimir. "Idealism and Art". Musical Courier, May 10, 1923.

"Mussorgsky in his songs invents a completely new medium of musical expressions. He arrives at complete realism, and has a perfect realistic musical tone that portrays the meaning of the word, the psychological state behind the word. He again demands another type of singer, a singer who can master an infinite number of colors in his tones—a singer able to portray in his tone not only beauty and fluent melodic lines, but also the grotesque, and paint realistic pictures with his voice.

In the days of the classics the purists were right—the tone was before everything else. With the sound-treasures that exist in the present-day songs, which portray all of the emotional sides of our life, then I say they are wrong and we are right. Let the purists say that they do not like that kind of song; that is different, and then it would be a question of taste. But to sing those songs with just pure tone is inartistic."

Rosing, Vladimir. "Interpretation in the Art of Singing – Part I". Musical Courier, October 11, 1923

"When a singer takes up a song for study he must, first of all, visualize the poem from the beginning to the end. He must create in his mind, a sort of cinematographic film of every movement or emotion that there is in the song. After that he has to place himself into the picture and live in it, becoming actually the character or characters there are in the songs and completely losing his own personality."

Rosing, Vladimir. "Interpretation in the Art of Singing, Part II". Musical Courier, October 18, 1923

"To such pitch has Mr. Rosing carried characterizing purpose and projecting power that the listener forgets the song in the singer. A more 'personal' concert then one of Mr. Rosing's is rare indeed. Not even Chaliapin's are more pervaded by a single spirit. He proffers a few words of explanation of his songs; he ventures a happy interchange, Russian-wise, with his audience. He spares neither his own nor the audience’s emotion.

When he believes that pure song is voice to the music in hand, he sings with clear regard for well-shaped, transparent tone, sustained line, warm, felicitous Italian phrasing, adept modulation, spun transition, plastic progress, apt climax.

Mr. Rosing prefers to make his song an insistently expressive art. In his tones he would define and project character; summon picture and vision, evoke and convey passions of the mind, the soul, the body. And he would do all these things to the utmost. For such purpose, he bends or breaks rhythms, chops or fuses phrases, zigzags the melodic line, sharply changes pace or accent, emphasizes contrast, multiplies climax. To gain these ends he uses unashamed what the vestal virgins of song call vocal tricks—the falsetto, for example, or the long-sustained note, swelled, diminished, melted almost inaudibly into the air. He uses them, however, not as display in Galli-Curcian or Tetrazzinian fashion, but to achieve a discoverable point in his vocal design. Above all else, Mr. Rosing would color his tones and impress upon his hearers the personage, the passion, the picture of music and verse as they have stirred his spirit. If the accepted arts of song will so serve him, he uses them expertly, effectively. If they are less viable, he chooses his own means, employs them in his own way."

Parker, H. T. Eighth Notes: Voices and Figures of Music and the Dance (1922). New York, Dodd, Mead & Co.

"Rosing brought to London a style of song and of singing London had never heard before, a stark, realistic Russian song, put over in a stark, realistic Russian manner. London concert halls and drawing rooms... lapped up this neat vodka as avidly as a man who has spent months in the desert or a monastery. The fellow, it was plain, was a savage, a moujik. A vagabond of the Steppes, a wastrel from the Siberian snows. Men were shaken out of their complacency. Women shuddered—and adored him.

Rosing had one of the vividest and most magnetic personalities I had ever come across; rarely have I known anyone who could hold an audience in such a sheer ecstasy of enchantment through a whole recital. A Rosing audience was unlike any other. There was electricity in the air and people crouched forward in their seats as though they were watching some fierce and terrifying melodrama. With Rosing, nearly every song was a melodrama—sometimes a grand guignol melodrama. He acted every song; often he overacted it, sometimes he all but clowned it. The purists were scandalized. The man could do everything but sing, they said. He was a mountebank, a buffoon. He had no right in a concert hall; he ought to be on a fairground. It was outrageous, unparalleled. So it was. Perhaps they were right, but it came off, because, despite all his eccentricities, Rosing was never cheap; in everything he did there was such an overpowering impression of stern, unflinching sincerity. The man simply threw himself into his music and its poem. He sang—eyes closed and feet wide apart, like a blind goalkeeper—not only with his voice but with his heart, brain, body, hands and feet. If he tore a passion to tatters, you felt that that particular passion was much more effective in tatters than intact. If he made a mess of a song, well, it was a glorious mess."

Newton, Ivor. At the Piano, the world of an accompanist (1966). Hamish Hamilton, London.

Popular Culture

Vladimir Rosing may have partly inspired the character of Stanislas Rosing in English author Lady Eleanor Smith's 1932 romance novel "Ballerina". Eleanor Smith (1902–1945) was the daughter of F. E. Smith and the sister of Frederick Smith, 2nd Earl of Birkenhead, both of whom Vladimir Rosing socialized with. The novel was subsequently made into a film in 1941 called "The Men in Her Life", starring Loretta Young. The character of Rosing was played by Conrad Veidt. Coincidentally, the film's Russian-born director, Gregory Ratoff, was also a long-time friend of Vladimir Rosing.

Rosing appears as the character of Vladimir Arenkoff in Pulitzer Prize-winning author Paul Horgan's second novel "The Fault of Angels". A fictionalization of the personalities surrounding the American Opera Company in Rochester, the novel won the Harper Prize in 1933.

Irish poet Patrick MacDonogh (1902–1961) writes about listening to Vladimir Rosing's recording of Rachmaninoff's "Ne poy krasavitsa, pri mne" in part two of his poem "Escape to Love".[95]

Notes

- ↑ Before the first successes of his musical career, Rosing held the post of Bridge Editor for the popular British publication The Strand Magazine from September 1911 to February 1912 under the byline Wladimir de Rozing.[17]

- ↑ Also during this period Rosing was treated briefly by Dr. Roger Vittoz in Lausanne, Switzerland. Rosing credited Vittoz with changing his life and providing him with the tools to harness his mental and creative energies to their fullest. Rosing built upon Vittoz' ideas and later incorporated many of them into his training methods for singers and actors. T. S. Eliot was also a patient of Vittoz.[19]

- ↑ Portrait of Vladimir Rosing by Glyn Philpot R.A. was included Philpot's 1938 Exhibition of Paintings and Sculpture at London's Tate Gallery. Since 1964 it has been in the collection of Lord Salisbury at Hatfield House.[25]

- ↑ Rosing's meeting with Prime Minister Lloyd George was the subject of debate in the House of Commons. Andrew Bonar Law, Leader of the House of Commons, was questioned by M.P. Joseph King whether or not Lloyd George had secretly met with Rosing to discuss Chicherin's release. Bonar Law said he was told that no such meeting took place. Rosing's personal memoirs confirm that it did.[30]

- ↑ William Bullitt and Vladimir Rosing met almost nightly during this period with the purpose of writing a play about the Russian Revolution. They could not agree on a plot, but Rosing eventually did write a play on the subject: "The Crown Changes Hands".[41]

- ↑ Time magazine misreported on December 26, 1927, that Rosling met Eastman himself en route to Europe, and that error has been often repeated, even by original members of the American Opera Company, Paul Horgan and Nicholas Slonimsky, and by Elizabeth Brayer in her definitive biography of George Eastman.[43]

- ↑ Attending a performance at the Bowl was Rosing's friend and teacher, Paramahansa Yogananda. Rosing first met Yogananda in Seattle in 1925. Along with Amelita Galli-Curci. Rosing was one of Yogananda's primary celebrity endorsers. Yogananda went to Rochester to visit Rosing in December 1926. Rosing was also intensely interested in Theosophy, and knew the movement's President, Annie Besant. When he returned to England in the 1930s he was a regular guest at Christmas Humphreys' London Buddhist Lodge along with the young Alan Watts.[80][81][82][83]

- ↑ Valerian became a well-known crooner in the 1930s under the stage name Val Rosing, causing occasional confusion with his well-known father. He released dozens of records and is the vocalist on the original version of Teddy Bears' Picnic. He was brought to Hollywood by MGM in 1937 and changed his name to Gilbert Russell.[93][94]

References

- ↑ "Chaliapin and Rosing Typify Russian Music", Christian Science Monitor, April 1, 1922. pg. 16.

- ↑ Shaw, George Bernard. The Perfect Wagnerite, 4th Edition., p. 132, London: Constable & Co. (1923).

- ↑ Hogarth, Basil. "Igor Stravinsky: The Stormy Petrel of Music". The Gramophone, June 1935. pg. 7.

- ↑ Ewen, David. Living Musicians, pg. 301., New York: H. W. Wilson Co. (1940)

- ↑ Rosing, Ruth Glean. "Val Rosing's Technique of Acting for Singers", The New York Opera Newsletter, pg. 7. May 1995.

- ↑ Rosing, Ruth Glean. Val Rosing: Musical Genius. pg. 8, Manhattan: Sunflower University Press (1993).

- ↑ Val Rosing pg. 10-14.

- ↑ Val Rosing pg. 14-16.

- ↑ Ascher, Abraham. P. A. Stolypin: The Search for Stability in Late Imperial Russia, pg. 13-14. Stanford; Stanford University Press (2001)

- ↑ Val Rosing pg. 20-21.

- ↑ Val Rosing pg. 22-25.

- ↑ Val Rosing pg. 26-27.

- ↑ Val Rosing pg. 34.

- ↑ Val Rosing pg. 37-40.

- ↑ Juynboll, Floris. "Vladimir Rosing", The Record Collector, Vol. 36 No. 3, July, August, September 1991. pg. 187

- ↑ Val Rosing pg. 46.

- ↑ The Strand Magazine, An Illustrated Monthly, Vol. 42 & Vol. 43. 1911-1912

- ↑ Manuscript of Memoirs by Vladimir Rosing, Bakhmeteff Archive - Columbia University

- ↑ Manuscript of Memoirs by Vladimir Rosing, Bakhmeteff Archive - Columbia University

- ↑ Juynboll, Floris. "Vladimir Rosing", The Record Collector Vol. 36 No. 3, July, August, September 1991. pg. 192-194

- ↑ Manuscript of Memoirs by Vladimir Rosing, Bakhmeteff Archive - Columbia University

- ↑ Newton, Ivor. At the Piano: the world of an accompanist, pg. 44, London: Hamish Hamilton (1966)

- ↑ At the Piano. pg. 47.

- ↑ At the Piano, pg. 44.

- ↑ Illustrated Catalogue: Exhibition of Paintings and Sculpture by the Late Glyn Philpot, R.A. (1884-1937). pg. 9, London: Tate Gallery, Millbank. July 14, 1938 to August 28, 1938.

- ↑ Williams, Gordon. British Theatre in The Great War: a reevaluation pg. 271-273., New York: Continuum (2003)

- ↑ Val Rosing pg. 70.

- ↑ Wilson, Trevor. The Political Diaries of C. P. Scott 1911-1928. p. 270-271. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, NY (1970).

- ↑ Manuscript of Memoirs by Vladimir Rosing, Bakhmeteff Archive - Columbia University

- ↑ House of Commons Debates, 15 Jan 1918, Vol 101 cc 136-8.

- ↑ Manuscript of Memoirs by Vladimir Rosing, Bakhmeteff Archive - Columbia University

- ↑ The Political Diaries of C. P. Scott 1911-1928. p. 346-348.

- ↑ At the Piano, pg. 44.

- ↑ At the Piano, pg. 47.

- ↑ Living Musicians, pg. 301.

- ↑ Juynboll, Floris. "Vladimir Rosing", The Record Collector Vol. 36 No. 3, July, August, September 1991. pg. 194-196

- ↑ Boult, Adrian Cedric. My Own Trumpet (1973), p.48, Hamish Hamilton, London.

- ↑ Manuscript of Memoirs by Vladimir Rosing, Bakhmeteff Archive - Columbia University

- ↑ "President Host to Chief Justice Taft". New York Times. February 3, 1922. Retrieved May 2, 2015.

- ↑ "For Russian Relief". New York Times. March 5, 1922. Retrieved May 2, 2015.

- ↑ Manuscript of Memoirs by Vladimir Rosing, Bakhmeteff Archive - Columbia University

- ↑ Eaton, Quaintance. "Advance Guard". Opera News. February 27, 1971. p. 28.

- ↑ Manuscript of Memoirs by Vladimir Rosing, Bakhmeteff Archive - Columbia University

- ↑ Manuscript Memoirs of Vladimir Rosing, Bakhmeteff Archive - Columbia University

- ↑ "Val Rosing's Technique of Acting for Singers", pg. 7.

- ↑ Eaton, Quaintance. "Advance Guard". Opera News. February 27, 1971. p. 28-30.

- ↑ "Operatic Department for Eastman School of Music", Christian Science Monitor, August 25, 1923. pg. 10.

- ↑ "Rosing Gives Thrilling Program—Demonstrates Theories", Saskatoon Phoenix, Dec 11, 1923.

- ↑ Downes, Olin. "Music", New York Times, Oct 21, 1924. pg. 21.

- ↑ Warner, A. J., "Rochester American Opera Company Makes Debut", Rochester Times Union, Nov 21, 1924.

- ↑ Lenti, Vincent A. For the Enrichment of Community Life: George Eastman and the Founding of the Eastman School of Music. p. 135. Meliora Press, Rochester, NY (2004).

- ↑ "An Opera Without A Star Role", The Washington Post, pg. F1, November 20, 1927.

- ↑ Goossens, Eugene. Overture and Beginners. p. 135. Methuen & Co. Ltd. London (1951).

- ↑ Graf, Herbert. Opera for the People, pg. 158., Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press (1951).

- ↑ "To Rehearse Operas: New American Company Will Leave for Gloucester Tomorrow". New York Times July 8, 1927

- ↑ "Opera in American for Americans", Literary Digest, January 28, 1928.

- ↑ Letter from President Herbert Hoover to the Speaker of the House expressing support for the American Opera Company, February 27, 1930. The American Presidency Project

- ↑ Slonimsky, Nicolas. Perfect Pitch: A Life Story. p. 92. Oxford University Press, Oxford. (1988).

- ↑ Val Rosing pg. 120-121

- ↑ "Mr. Rosing's Return to London", The Morning Post, London. Oct 30, 1933.

- ↑ The Gramophone, Feb 1938, pg. 390.

- ↑ Val Rosing pg. 123.

- ↑ Herbert, Stephen A., History of Early Television Vol 2., (2004), p. 86-87. Routledge.

- ↑ Squire, W. H. Haddon. "The Circle", Christian Science Monitor, Jan 19, 1937. pg. 13.

- ↑ "Television Programme as Broadcast: Wednesday 5 Oct 1938", BBC, pg. 3.

- ↑ Rosenthal, Harold. Opera at Covent Garden (1967) London: Gollancz

- ↑ Moore, Jerrold Northrop. Sound Revolutions: A Biography of Fred Gaisberg, Founding Father of Commercial Sound Recording, pg. 323, London: Sanctuary Publishing Ltd. (1999)

- ↑ Val Rosing pg. 129.

- ↑ Anderson, Richard H., "Val Rosing, Musical Show Director, Finishes Successful Period Here", Camp Roberts Dispatch, Nov 16, 1945.

- ↑ Letter from Lt. Col F. A. Small to Val Rosing, Dec 22, 1945. Estate of Vladimir Rosing.

- ↑ Opera for the People, pg. 173.

- ↑ Opera for the People, pg. 223.

- ↑ "The Love for Three Oranges: A Slaphappy Fairy Tale Makes a Smash-Hit Opera", Life Magazine, Nov 1949.

- ↑ Kolodin, Irving. "Music to My Ears", Saturday Review, Apr 19, 1958. pg. 35.

- ↑ MacKay, Harper. "Going Hollywood: How Opera's Superstars Made Their Way to Tinseltown", Opera News, Apr 13, 1991. pg. 54.

- ↑ Goldberg, Albert., "10,000 Cheer Ingenious Bowl Productions at Gala Opening", Los Angeles Times, Jul 8, 1950.

- ↑ "Willson Named to Direct State Pageant Music", Los Angeles Times, Aug 11, 1950.

- ↑ Ainsworth, Ed., "Narration by Barrymore Highlight of Pageant", Los Angeles Times, Sept 13, 1950.

- ↑ Official program, Fiesta del Pacifico, San Diego, 1956

- ↑ Kriyananda, Swami & Walters, J. Donald., God is For Everyone, pg. 77, Nevada City: Crystal Clarity Publishers (2003)

- ↑ Swami's Christmas Holidays", East West, November—December, 1926 Vol. 2—1" East West

- ↑ Letter from Annie Besant to Vladimir Rosing, August 26, 1926. Estate of Vladimir Rosing

- ↑ Watts, Alan, In My Own Way: An Autobiography, pg. 79-80., Novato: New World Library (2007).

- ↑ Lyric Opera of Chicago 1954-1963. R. R. Donnelley & Sons, Chicago (1963).

- ↑ Brotman, Ruth C. Pauline Donalda: The Life and Career of a Canadian Prima Donna (1975) p. 100-101. The Eagle Publishing Company Ltd. Montreal

- ↑ "Pageant Thrills in Scope and Beauty: California Story Rated Powerful Entertainment", San Diego Evening Tribune, July 29, 1957. pg. A-10.

- ↑ Pratt, Gerry., "First Nighters at Centennial's Historic Oregon Story Find Lavish Entertainment, Vivid Re-enactment of Past", The Oregonian, Sept 4, 1959.

- ↑ Reed, R. W., "Kansas Story Impressive", Wichita Eagle and Beacon, June 16, 1961

- ↑ "Arizona Story Worthy of Name", The Phoenix Gazette, April 20, 1963.

- ↑ Val Rosing pg. 212-216.

- ↑ Val Rosing pg. 219-220.

- ↑ "Vladimir Rosing, Director, 73, Dies", New York Times, Nov 27, 1963.

- ↑ Pallett, Ray. "Val Rosing: From band singer to grand opera, Part One", Memory Lane, Issue 122 Spring 1999, pg. 33.

- ↑ Pallett, Ray. "Val Rosing: From band singer to grand opera, Part Two", Memory Lane, Issue 123 Summer 1999, pg. 33.

- ↑ MacDonogh, Patrick. Poems, pg. 64., Loughcrew: Gallery Books (2001).

External links

- Parlophone Album: Songs of Famous Russian Composers, 1937

- Parlophone Album: Fourteen Songs of Modest Mussorgsky, 1935

- Vladimir Rosing - Opera Recordings, 1912-1925

- Vladimir Rosing Discography

- Vladimir Rosing: Memoirs of A Social, Political & Artistic Life

- Finding Dzhulynka - documentary film

- Vladimir Rosing BBC Interview

- Russian Records - Vladimir Rosing

- Find A Grave