People's Court (Germany)

The People's Court (German: Volksgerichtshof) was a Sondergericht ("special court") of Nazi Germany, set up outside the operations of the constitutional frame of law. Its headquarters were originally located in the former Prussian House of Lords in Berlin, later moved to the former Königliches Wilhelms-Gymnasium at Bellevuestrasse 15 in Potsdamer Platz (the location now occupied by the Sony Center; a marker is located on the sidewalk nearby).[1]

The court was established in 1934 by order of Nazi leader Adolf Hitler, in response to his dissatisfaction at the outcome of the Reichstag fire trial, in which all but one of the defendants was acquitted. The court had jurisdiction over a rather broad array of "political offenses", which included crimes like black marketeering, work slowdowns, defeatism, and treason against the Third Reich. These crimes were viewed by the court as Wehrkraftzersetzung ("disintegration of defensive capability") and were accordingly punished severely; the death penalty was meted out in numerous cases.

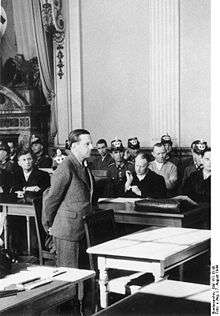

The Court handed down an enormous number of death sentences under Judge-President Roland Freisler, including those that followed the plot to kill Hitler on 20 July 1944. Many of those found guilty by the Court were executed in Plötzensee Prison in Berlin. The proceedings of the court were often even less than show trials in that some cases, such as that of Sophie Scholl and her brother Hans Scholl and fellow White Rose activists, trials were concluded in less than an hour without evidence being presented or arguments made by either side. The president of the court often acted as prosecutor, denouncing defendants, then pronouncing his verdict and sentence without objection from defense counsel, who usually remained silent throughout. It almost always sided with the prosecution, to the point that being hauled before it was tantamount to a death sentence. While Nazi Germany was not a rule of law state, the People's Court frequently dispensed with even the nominal laws and procedures of regular German trials, and was thus easily characterized as a "kangaroo court".

Manner of proceedings

With almost no exceptions, cases in the People's Court had predetermined guilty verdicts. There was no presumption of innocence nor could the defendants adequately represent themselves or consult an attorney. A proceeding at the People's Court would follow an initial indictment in which a state or city prosecutor would forward the names of the accused to the Volksgerichtshof for charges of a political nature. Defendants were hardly ever allowed to speak to their attorneys beforehand and when they did the defense lawyer would usually simply answer questions about how the trial would proceed and refrain from any legal advice. In at least one documented case (the trial of the "White Rose" conspirators), the defense lawyer assigned to Sophie Scholl chastised her the day before the trial, stating that she would pay for her crimes.

The People's Court proceedings began when the accused were led to a prisoner's dock under armed police escort. The presiding judge would read the charges and then call the accused forward for "examination". Although the court had a prosecutor, it was usually the judge who asked the questions. Defendants were often berated during the examination and never allowed to respond with any sort of lengthy reply. After a barrage of insults and condemnation, the accused would be ordered back to the dock with the order "examination concluded".

After examination, the defense attorney would be asked if they had any statements or questions. Defense lawyers were present simply as a formality and hardly any ever rose to speak. The judge would then ask the defendants for a statement during which time more insults and berating comments would be shouted at the accused. The verdict, which was almost always "guilty", would then be announced and the sentence handed down at the same time. In all, an appearance before the People' Court could take as little as fifteen minutes.

Prior to the Battle of Stalingrad, there was a higher percentage of cases in which not guilty verdicts were handed down on indictments. In some cases, this was due to defense lawyers presenting the accused as naive or the defendant adequately explaining the nature of the political charges against them. However, in nearly two thirds of such cases, the defendants would be re-arrested by the Gestapo following the trial and sent to a concentration camp. After the defeat at Stalingrad, and with a growing fear in the German government regarding defeatism amongst the population, the People's Court became far more ruthless and hardly any brought before the tribunal escaped a guilty verdict.[2]

The trials of August 1944

The best-known trials in the People's Court began on 7 August 1944, in the aftermath of the 20 July plot that year. The first eight men accused were Erwin von Witzleben, Erich Hoepner, Paul von Hase, Peter Yorck von Wartenburg, Helmuth Stieff, Robert Bernardis, Friedrich Klausing, and Albrecht von Hagen. The trials were held in the imposing Great Hall of the Berlin Chamber Court on Elßholzstrasse,[3] which was bedecked with swastikas for the occasion and there were around 300 spectators including Ernst Kaltenbrunner and selected civil servants, party functionaries, military officers and journalists. A film camera ran behind the red-robed Roland Freisler so that Hitler could view the proceedings, and to provide footage for newsreels and a documentary entitled Traitors Before the People's Court.[4] The last documentary of Die Deutsche Wochenschau, it was not shown at the time.[4]

The accused were forced to wear shabby clothes, denied neck ties and belts or suspenders for their pants, and were marched into the courtroom handcuffed to policemen. The proceedings began with Freisler announcing he would rule on "...the most horrific charges ever brought in the history of the German people." Freisler was an admirer of Andrey Vyshinsky, the chief prosecutor of the Soviet purge trials, and copied Vyshinsky's practice of heaping loud and violent abuse on defendants.

The 62-year-old Field Marshal von Witzleben was the first to stand before Freisler and he was immediately bawled at for giving a brief Nazi salute. He faced further humiliating insults while holding onto his trouser waistband. Next, former Colonel-General Erich Hoepner, dressed in a cardigan, faced Freisler, who addressed him as "Schweinehund". When he said that he was not a Schweinehund, Freisler asked him what zoological category he thought he fitted into.

The accused were unable to consult their lawyers, who were not seated near them. None of them were allowed to address the court at length, and Freisler interrupted any attempts to do so. However, Major General Helmuth Stieff attempted to raise the issue of his motives before being shouted down, and Witzleben managed to call out "You can hand us over to the hangman. In three months the enraged and tormented people will drag you alive through the muck of the streets." All were condemned to death by hanging, and the sentences were carried out shortly afterwards in Plötzensee prison.

Another trial of plotters was held on 10 August. On that occasion the accused were Erich Fellgiebel, Alfred Kranzfelder, Fritz-Dietlof von der Schulenburg, Georg Hansen and Berthold Schenk Graf von Stauffenberg.

On 15 August, Wolf-Heinrich Graf von Helldorf, Egbert Hayessen, Hans Bernd von Haeften, and Adam von Trott zu Solz were condemned to death by Freisler.

On 21 August, the accused were Fritz Thiele, Friedrich Gustav Jaeger and Ulrich Wilhelm Graf Schwerin von Schwanenfeld who was able to mention the "...many murders committed at home and abroad" as a motivation for his actions.

On 30 August, Colonel-General Carl-Heinrich von Stülpnagel, who had blinded himself in a suicide attempt, was led into the court and condemned to death along with Caesar von Hofacker, Hans Otfried von Linstow, and Eberhard Finckh.

Bombing of People's Court

Field Marshal von Witzleben's prediction with regards to Roland Freisler's fate proved slightly incorrect, as he died in a bombing raid in February 1945, approximately half a year later.[5][6]

On 3 February 1945, Freisler was conducting a Saturday session of the People's Court, when USAAF Eighth Air Force bombers attacked Berlin. Government and Nazi Party buildings were hit, including the Reich Chancellery, the Gestapo headquarters, the Party Chancellery and the People's Court. According to one report, Freisler hastily adjourned court and had ordered that day's prisoners to be taken to a shelter, but paused to gather that day's files. Freisler was killed when an almost direct hit on the building caused him to be struck down by a beam in his own courtroom.[..] His body was reportedly found crushed beneath a fallen masonry column, clutching the files that he had tried to retrieve. Among those files was that of Fabian von Schlabrendorff, a 20 July Plot member who was on trial that day and was facing execution.[..]

According to a different report, Freisler "was killed by a bomb fragment while trying to escape from his law court to the air-raid shelter", and he "bled to death on the pavement outside the People's Court at Bellevuestrasse 15 in Berlin." Fabian von Schlabrendorff was "standing near his judge when the latter met his end."[..]

Freisler's death saved Schlabrendorff, who after the war became a judge of the Constitutional Court of the Federal Republic of Germany (Bundesverfassungsgericht).

Yet another version of Freisler's death states that he was killed by a British bomb that came through the ceiling of his courtroom as he was trying two women, who survived the explosion.[..]

A foreign correspondent reported, "Apparently nobody regretted his death."[..] Luise Jodl, then the wife of General Alfred Jodl, recounted more than 25 years later that she had been working at the Lützow Hospital when Freisler's body was brought in, and that a worker commented, "It is God's verdict." According to Mrs Jodl, "Not one person said a word in reply."[..]

Freisler is interred in the plot of his wife's family at the Waldfriedhof Dahlem cemetery in Berlin. His name is not shown on the gravestone.

Notable people sentenced to death by the Volksgerichtshof

- 1942 – Helmuth Hübener. At the age of 17, he was the youngest opponent of the Third Reich executed as a result of a trial by the Volksgerichtshof.

- 1942 - Maria Restituta Kafka. A Catholic nun and surgical nurse who was found guilty of distributing regime-critical pamphlets.

- 1943 – Otto and Elise Hampel. The couple carried out civil disobedience in Berlin, were caught, tried, sentenced to death by Freisler, and executed. Their story formed the basis for the 1947 Hans Fallada novel Every Man Dies Alone/Alone in Berlin.

- 1943 – Members of the White Rose resistance movement: Sophie Scholl, Hans Scholl, Alex Schmorell, Willi Graf, Christoph Probst, and Kurt Huber.

- 1943 – Julius Fučík. A Czechoslovakian journalist, Communist Party of Czechoslovakia leader, and a leader in the forefront of the anti-Nazi resistance. On 25 August 1943, in Berlin, he was accused of high treason in connection with his political activities. He was found guilty and beheaded two weeks later on 8 September 1943.

- 1943 – Karlrobert Kreiten. A German pianist. Nazi Ellen Ott-Monecke notified the Gestapo of Kreiten's negative remarks about Adolf Hitler and the war effort. Kreiten was indicted at the Volksgerichtshof, with Freisler presiding, and condemned to death. Friends and family frantically tried to save his life to no avail. The family was never notified officially about the judgment. They only accidentally learned that Kreiten had been executed with 185 other inmates in Plötzensee Prison.

- 1943 - Max Sievers. A Communist and former chairman of the German Freethinkers League. He fled to Belgium after the Nazis came to power, but they caught up with him after invading that country. He was convicted of "conspiracy to commit high treason along with favouring the enemy", sentenced to death, and beheaded by guillotine on 17 February 1944.

- 1944 – Max Josef Metzger. A German Catholic priest. Metzger was the founder in 1938 of the "Una Sancta Brotherhood", an ecumenical movement for bringing Catholics and Protestants to unity. During the trial Freisler said that people like Metzger (meaning clergy) should be "eradicated."

- 1944 – Erwin von Witzleben. A German Field Marshal (Generalfeldmarschall). Witzleben was a German Army (Wehrmacht) conspirator in the 20 July Bomb Plot to kill Hitler. Witzleben, who would have been Commander-in-Chief of the Wehrmacht in the planned post-coup government, arrived at Army Headquarters (OKH-HQ) in Berlin on 20 July to assume command of the coup forces. He was arrested the next day and tried by the People's Court on 8 August. Witzleben was sentenced to death and hanged the same day in Plötzensee Prison.

- 1944 – Johanna "Hanna" Kirchner. A member of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands, SPD).

- 1944 – Lieutenant-Colonel Caesar von Hofacker. A member of a resistance group in Nazi Germany. Hofacker's goal was to overthrow Hitler.

- 1944 – Carl Friedrich Goerdeler – Conservative German politician, economist, civil servant and opponent of the Nazi regime, who would have served as the Chancellor of the new government had the 20 July plot of 1944 succeeded.

- 1944 – Otto Kiep – the Chief of the Reich Press Office (Reichspresseamts), which became involved in resistance.

- 1944 – Elisabeth von Thadden, as well as other members of anti-Nazi Solf Circle.

- 1944 – Julius Leber – German politician of the SPD and a member of the German Resistance against the Nazi régime.

- 1944 – Johannes Popitz – Prussian finance minister and a member of the German Resistance against Nazi Germany.

- 1945 – Helmuth James Graf von Moltke – German jurist, a member of the opposition against Adolf Hitler in Nazi Germany, and a founding member of the Kreisau Circle dissident group.

- 1945 – Klaus Bonhoeffer and Rüdiger Schleicher – German resistance fighters.

- 1945 – Erwin Planck. Politician, businessman, resistance fighter and son of physicist Max Planck. Planck was an alleged conspirator in the 20 July plot.

- 1945 – Arthur Nebe. An SS-General (Gruppenführer). Nebe was a conspirator in the 20 July Bomb Plot to kill Hitler. He was the head of the Kriminalpolizei, or Kripo, and the commander of Einsatzgruppe B. Nebe oversaw massacres on the Russian Front, and at other locations as he was commanded to do by his superiors in the SS. After the failure to assassinate Hitler, Nebe hid on an island in the Wannsee until he was betrayed by one of his mistresses. On 21 March 1945 Nebe was hanged, allegedly with piano wire (Hitler wanted members of the plot "hanged like cattle"[7]) at Plötzensee Prison.

Judge-Presidents of the People's Court

- Fritz Rehn: 13 July – 18 September 1934

- Otto Georg Thierack: 1936 – August 1942

- Roland Freisler: 20 August 1942 – 3 February 1945

- Harry Haffner: 12 March – 24 April 1945

Legal aftermath after World War II

In 1956 the German Federal High Court of Justice (Bundesgerichtshof) granted the so-called “Judges' Privilege” to those that had been part of the Volksgerichthof. This prevented the prosecution of the former Volksgerichthof members on the basis that their actions had been legal under the laws in effect during the Third Reich.

The only member of the Volksgerichthof ever to be held liable for their actions was Chief Public Prosecutor Ernst Lautz, who in 1947 was sentenced to 10 years of imprisonment by a US Military Tribunal, during the Judges' Trial, one of the “subsequent Nuremberg proceedings”. Ernst Lautz was pardoned after serving less than four years of his sentence and was granted a government pension.

Of the other approx. 570 judges and prosecutors, none were held responsible for their actions related to the Volksgerichtshof. In fact, many had careers in the West-German post-war legal system:

- Paul Reimers: Regional court judge in Ravensburg

- Hans-Dietrich Arndt: Chief judge, Koblenz district court.

- Robert Bandel: Chief district judge in Kehl

- Karl-Hermann Bellwinkel: First district attorney in Bielefeld

- Erich Carmine: Court judge in Nuremberg

- Christian Dede: Director of the Hannover district court

- Johannes Frankenberg: Court judge in Münnerstadt

- Andreas Fricke: Court judge in Braunschweig

- Konrad Höher: District attorney in Cologne

See also

- List of members of the July 20 Plot

- Sondergerichte (Special Courts)

- People's Court (Bavaria)

References

- ↑ CRIME, GUNS, AND VIDEOTAPE: Meet "The People's Court"

- ↑ Roberts, G., Victory at Stalingrad: The Battle That Changed History, Routledge (2002), ISBN 0582771854

- ↑ H.W.Koch (1997). In the Name of the Volk: Political justice in Hitler's Germany. I B Tauris & Co Ltd. ISBN 978-1-86064-174-9.

- 1 2 Robert Edwin Hertzstein, The War That Hitler Won p283 ISBN 0-399-11845-4

- ↑ Ian Kershaw (2000). Hitler 1936–1945: Nemesis. Penguin Press. ISBN 0-393-32252-1.

- ↑ Joachim Fest (1994). Plotting Hitler's Death: The German Resistance to Hitler, 1933–1945. Weidenfield & Nicholson. ISBN 0-297-81774-4.

- ↑ William Shirer, The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich,pp 1393