Wake in Fright

| Wake in Fright | |

|---|---|

|

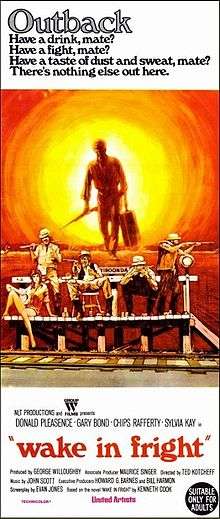

Original Australian theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Ted Kotcheff |

| Produced by | George Willoughby |

| Screenplay by | Evan Jones |

| Based on |

Wake in Fright by Kenneth Cook |

| Starring |

Gary Bond Donald Pleasence Chips Rafferty |

| Music by | John Scott |

| Cinematography | Brian West |

| Edited by | Anthony Buckley |

Production company | |

| Distributed by |

United Artists (1971) Drafthouse Films (2012) |

Release dates | |

Running time | 114 minutes[2] |

| Country |

Australia United States |

| Language | English |

Wake in Fright (also known as Outback) is a 1971 Australian thriller film directed by Ted Kotcheff and starring Gary Bond, Donald Pleasence and Chips Rafferty. The screenplay, written by Evan Jones, is based on Kenneth Cook's 1961 novel of the same name. An Australian and American venture produced by Group W and NLT Productions, Wake in Fright tells the story of a young schoolteacher from Sydney who descends into personal moral degradation after finding himself stranded in a brutal, menacing town in outback Australia.

For many years, Wake in Fright enjoyed a reputation as Australia's great "lost film" because of its unavailability on VHS or DVD, as well as its absence from television broadcasts. In mid-2009, however, a thoroughly restored digital re-release was shown in Australian theatres to considerable acclaim. Later that year it was issued commercially on DVD and Blu-ray Disc. Wake in Fright is now considered a seminal film of the Australian New Wave[3] and has been ranked by critics as one of the greatest Australian films.

A made-for-television film remake is set to be released in 2017.

Plot

John Grant is a middle-class teacher from the big city. He feels disgruntled because of the onerous terms of a financial bond which he signed with the government in return for receiving a tertiary education. The bond has forced him to accept a post to the tiny school at Tiboonda, a remote township in the arid Australian Outback. It is the start of the Christmas school holidays and Grant plans on going to Sydney to visit his girlfriend, but first he must travel by train to the nearby mining town of Bundanyabba (known as "the Yabba”) in order to catch a Sydney-bound flight.

At the Yabba, Grant encounters several disconcerting residents including a policeman, Jock Crawford, who encourages Grant to drink repeated glasses of beer before introducing him to the local obsession with the gambling game of two-up. Hoping to win enough money to pay off his bond and escape his indentured servitude as an outback teacher, Grant at first has a winning streak playing two-up but then loses all his cash. Unable now to leave the Yabba, Grant finds himself dependent on the charity of bullying strangers while being drawn into the crude and hard-drinking lifestyle of the town's residents.

Grant reluctantly goes drinking with a resident named Tim Hynes (Al Thomas) and goes to Tim's house. Here he meets Tim's daughter, Janette. While he and Janette talk, several men who have gathered at the house for a drinking session question Grant's masculinity, asking: “What's the matter with him? He'd rather talk to a woman than drink beer.” Janette then tries to initiate an awkward sexual episode with Grant, who vomits. Grant finds refuge of a sort, staying at the shack of an alcoholic medical practitioner known as Doc Tydon. Doc tells him that he and many others have had sex with Janette. He also gives Grant pills from his medical kit, ostensibly to cure Grant's hangover.

Later, a drunk Grant participates in a barbaric kangaroo hunt with Doc and Doc's friends Dick and Joe. The hunt culminates in Grant clumsily stabbing a wounded kangaroo to death, followed by a pointless drunken brawl between Dick and Joe and the vandalizing of a bush pub. At night's end, Grant returns to Doc's shack, where Doc apparently initiates a homosexual encounter between the two.[4]

A repulsed Grant leaves the next morning and walks across the desert. He tries to hitch-hike to Sydney, but, through misunderstanding, boards a truck that takes him straight back to the Yabba. He contemplates shooting Doc, but instead attempts suicide. Grant recovers in hospital from his suicide attempt and Doc sees him off at the Yabba's rail station. He returns to Tiboonda for the new school year.

Cast

- Gary Bond as John Grant

- Donald Pleasence as Doc Tydon

- Chips Rafferty as Jock Crawford

- Sylvia Kay as Janette Hynes

- John Meillon as Charlie

- Jack Thompson as Dick

- Peter Whittle as Joe

- Al Thomas as Tim Hynes

- Dawn Lake as Joyce

- John Armstrong as Atkins

- Slim de Grey as Jarvis

- Maggie Dence as receptionist

- Norman Erskine as Joe the cook

- Robert McDarra as Pig Eyes

Production

A film version of Wake in Fright, based on the 1961 novel by Kenneth Cook, was linked with the actor Dirk Bogarde and the director Joseph Losey as early as 1963. Morris West later secured the film rights and tried, unsuccessfully, to raise funding for the film's production. The rights were eventually bought by NLT and Group W. and Canadian director Ted Kotcheff was recruited to direct the film. At the time of production, Kotcheff had directed three films, Tiara Tahiti (1962), Life at the Top (1965) and Two Men Sharing (1969). After Wake in Fright, Kotcheff would continue to have a successful career as a director. His later films included The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz (1973), Fun with Dick and Jane (1977), First Blood (1982) and Weekend at Bernie's (1988).

The shooting of Wake in Fright began in January 1970 in the mining town of Broken Hill, New South Wales (the area which had inspired Cook for the setting of his novel), with interiors shot the next month at Ajax Studios in the Sydney beach-side suburb of Bondi. It was the last film to feature the veteran character actor Chips Rafferty, who died of a heart attack prior to Wake in Fright's release, and the first film with Jack Thompson, the future Australian cinema star, among its cast members. Coincidentally, Rafferty (real name John William Pilbean Goffage) had been born in Broken Hill, the film's stand-in for the Yabba, in 1909.

Release

The world premiere of Wake in Fright (as Outback) occurred at the 1971 Cannes Film Festival, held in May. Ted Kotcheff was nominated for a Golden Palm Award.[5] The film opened commercially in France on 22 July 1971, Great Britain on 29 October 1971, Australia during the same month and the United States on 20 February 1972.

Reception

Wake in Fright found a favourable public response in France, where it ran for five months, and in the United Kingdom. However, despite receiving such critical support at Cannes and in Australia, Wake in Fright suffered poor domestic box-office returns. Although there were complaints that the film's distributor, United Artists, had failed to promote the film successfully, it was also thought that the film was “perhaps too uncomfortably direct and uncompromising to draw large Australian audiences".[6] During an early Australian screening, one man stood up, pointed at the screen and protested "That's not us!", to which Jack Thompson yelled back "Sit down, mate. It is us."[7]

The un-restored version of Wake in Fright received a three stars (out of four) rating from the American film reviewer Leonard Maltin in his 2006 Movie Guide, while Brian McFarlane, writing in 1999 in The Oxford Companion to Australian Film, said that it was “almost uniquely unsettling in the history of new Australian Cinema”. Askmen.com echoed these sentiments, citing that "it's not hard to see why the dusty savagery and clown-faced surrealism of Ted Kotcheff's fourth feature was never shown on telly at the time."[8]

Following the film's restoration, Wake in Fright screened at the 2009 Cannes Film Festival on 15 May 2009 when it was selected as a Cannes Classic title by the head of the department, Martin Scorsese.[9] Wake in Fright is one of only two films ever to screen twice in the history of the festival.[10] Scorsese said, "Wake in Fright is a deeply -- and I mean deeply -- unsettling and disturbing movie. I saw it when it premiered at Cannes in 1971, and it left me speechless. Visually, dramatically, atmospherically and psychologically, it's beautifully calibrated and it gets under your skin one encounter at a time, right along with the protagonist played by Gary Bond. I'm excited that Wake in Fright has been preserved and restored and that it is finally getting the exposure it deserves."[11]

Roger Ebert reviewed the re-release and said "It's not dated. It is powerful, genuinely shocking and rather amazing. It comes billed as a 'horror film' and contains a great deal of horror, but all of the horror is human and brutally realistic."[12] Don Groves of SBS gave the film four stars out of five, claiming that "Wake in Fright deserves to rank as an Australian classic as it packs enormous emotional force, was bravely and inventively directed, and features superb performances. "[13] American critic Rex Reed, an early advocate of Wake in Fright, praised the film's restoration as "the best movie news of the year", and said it "may be the greatest Australian film ever made".[14] According to Australian musician and screenwriter Nick Cave, it is "the best and most terrifying film about Australia in existence."[15]

The film has an approval rating of 100% and a rating average score of 8.6 out of 10 on the review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, based on 46 reviews. The site's consensus states: "A disquieting classic of Australian cinema, Wake in Fright surveys a landscape both sun-drenched and ruthlessly dark."[16] Wake in Fright is also listed in the 2015 edition of the film reference book 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die.[17]

Controversy

In addition to the film's atmosphere of sordid realism, the kangaroo hunting scene contains graphic footage of kangaroos actually being shot.[18] A disclaimer at the conclusion of the movie states:

Producers' Note.The hunting scenes depicted in this film were taken during an actual kangaroo hunt by professional licensed hunters.

For this reason and because the survival of the Australian kangaroo is seriously threatened, these scenes were shown uncut after consultation with the leading animal welfare organisations in Australia and the United Kingdom.[19]

The hunt lasted several hours, and gradually wore down the filmmakers. According to cinematographer Brian West, "the hunters were getting really drunk and they started to miss, ... It was becoming this orgy of killing and we [the crew] were getting sick of it." Kangaroos hopped about helplessly with gun wounds and trailing intestines. Producer George Willoughby reportedly fainted after seeing a kangaroo "splattered in a particularly spectacular fashion". The crew orchestrated a power failure in order to end the hunt.[20]

At the 2009 Cannes Classic screening of Wake in Fright, 12 people walked out during the kangaroo hunt.[21]

Director Ted Kotcheff, a professed vegetarian,[22] has defended his use of the hunting footage in the film.[23]

Restoration and home-media releases

For many years, the only known print of Wake in Fright, found in Dublin, was considered of insufficient quality for transfer to DVD or videotape for commercial release. In response to this situation, Wake in Fright's editor, Anthony Buckley, began to search in 1994 for a better-preserved copy of the film in an uncut state. Ten years later, in Pittsburgh, Buckley found the negatives of Wake in Fright in a shipping container labelled "For Destruction". He rescued the material, which formed the basis for the film's painstaking 2009 restoration.[24] Evidently a 35mm print in excellent condition had also survived in the collection of the Library of Congress, which screened it in the library's Mary Pickford Theater in 2008, although its reported running time of only 96 minutes suggests this was an edited version.[25]

Wake in Fright was released on DVD and Blu-ray Disc formats on 4 November 2009,[26] based on a digital restoration completed earlier that year. This restoration was shown to the general public for the first time at the Sydney Film Festival in June 2009, and in re-release has been called "a classic Australian film which has achieved cult status".[27]

A made-for-television film remake is set to be released in 2017.[28]

Further reading

- Adams, B & Shirley, G. (1983) Australian Cinema: The First Eighty Years, Angus and Robertson, ISBN 0-312-06126-9

- Buckley, Anthony (2009) Behind a Velvet Light Trap: A Filmmaker's Journey from Cinesound to Cannes. Prahran: Hardie Grant Books. ISBN 978-1-74066-7906

- Caterson, S., (2006) "The Best Australian Film You've Never Seen", Quadrant, pp. 86–88, Jan–Feb 2006.

- Greenwood, P. (2006) Wake in Fright, Murdoch University, [wwwmcc.murdoch.edu.au/ReadingRoom/film/dbase/2006/wake.doc]. Accessed 15 January 2007.

- Kaufman, Tina (2010) Wake in Fright: Australian Screen Classics. Sydney: Currency Press. ISBN 978-0-86819-864-4

- McFarlane, B. (1999) The Oxford Companion to Australian Film, Melbourne: Oxford University Press, Melbourne. ISBN 978-0-19-553797-0

- Maddox, G. (2004) "Treasure, not trash: classic found in US", The Sydney Morning Herald, p 13, 16 October 2004.

- Maltin, L. (2006) Leonard Maltin's 2006 Movie Guide, Signet, ISBN 0-451-21609-1.

- Pike, A. & Cooper, R. (1998) Australian Film 1900–1977, Oxford University Press, Melbourne. ISBN 0-19-550784-3

- Williamson, G. (2006) “The Forum”, The Australian, p. 5, 30 December 2006.

- Zion, L. (2006) "DVD Letterbox", The Australian, p. 25, 29 July 2006.

- Hoey. Gregory [2012] "Wake in Fright:by an elephant in the room" a book of personal memoirs.

References

- ↑ "Wake in Fright: Post-production and release". National Film & Sound Library Australia. Retrieved 4 January 2012.

- ↑ "WAKE IN FRIGHT (18)". United Artists. British Board of Film Classification. 7 June 1971. Retrieved 30 September 2013.

- ↑ Rapold, Nicolas (4 October 2012). "'Wake in Fright' and Australian New Wave", The New York Times. Retrieved 12 January 2012.

- ↑ "Wake in Fright", Radio National review by Julie Rigg, 26 June 2009

- ↑ "Festival de Cannes: Wake in Fright". festival-cannes.com. Retrieved 13 April 2009.

- ↑ Scott, Matthew (12 December 2009). "Film (1971)". South China Morning Post. Hong Kong. Archived from the original on 4 November 2013. Retrieved 3 November 2013.

- ↑ Burton, Al (25 December 2014). "Wake in Fright". WorldCinemaGuide.com. Archived from the original on 5 November 2016.

- ↑ McCasker, Toby (n.d.). "Top 10: Weirdest Aussie Movies > No.4 Wake In Fright, 1971l". AskMen.com. Archived from the original on 2 October 2011.

- ↑ Breznican, Anthony (18 May 2009). "At Cannes, Martin Scorsese has his eyes on films long unseen". USA Today. Archived from the original on 26 July 2013. Retrieved 8 January 2012.

- ↑ "Australian National Film & Sound Archive Annual Report 2008-09" (PDF). National Film & Sound Archive Australia. Retrieved 8 January 2012.

- ↑ Peary, Danny (5 October 2012). "Ted Kotcheff on Wake in Fright". Retrieved 7 May 2013.

- ↑ Ebert, Roger (31 October 2012). "Wake in Fright". movie reviews. Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved 1 November 2012.

- ↑ Groves, Don. "Wake in Fright (review)". SBS. Retrieved 14 February 2013.

- ↑ Reed, Rex (2 October 2012). "A Beautiful Nightmare", The New York Observer. Retrieved 14 December 2012.

- ↑ Cave, Nick. "Wake in Fright (brand-new 35mm print!)", The Cinefamily. Retrieved 7 May 2013.

- ↑ "Wake in Fright Movie Reviews". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved December 23, 2012.

- ↑ Schneider, Steven Jay; Smith, Ian Haydn (2015). 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die. Murdoch Books Pty Limited. 9781743366165.

- ↑ "Wake in Fright - BBFC Insight". British Board of Film Classification. 28 January 2014. Retrieved 28 December 2014.

- ↑ Quoted from the movie credits.

- ↑ Galvin, Peter (22 March 2010). "The Making of Wake in Fright (Part Three)", SBS. Retrieved 7 January 2013.

- ↑ "Wake in Fright interview", At the Movies. Retrieved 7 January 2013

- ↑ Skinner, Craig (24 March 2014). "Ted Kotcheff discusses Wake in Fright, kangaroo slaughter and existentialism". Film Divider. Archived from the original on 27 December 2014. Retrieved 27 December 2014.

- ↑ Kotcheff, Ted (12 August 2012). "Wake in Fright - Director's Statement". Gene Siskel Film Center. Archived from the original on 21 December 2014. Retrieved 21 December 2014.

- ↑ "Wake in Fright: Recovery and restoration". National Film & Sound Library Australia. Retrieved 26 September 2013.

- ↑ "Past Screenings: Friday, June 27, 2008". Mary Pickford Theater. Library of Congress. Archived from the original on 28 December 2014. Retrieved 27 December 2014.

- ↑ "Wake in Fright (aka Outback)". Archived from the original on 2 February 2011.

- ↑ Baillie, Rebecca (22 April 2009). "'Wake in Fright' restored for re-release". The 7:30 Report. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 29 April 2009. Retrieved 22 April 2009.

- ↑ Idato, Michael (8 September 2016). "Wake in Fright joins TV's new wave of literary adaptations and film reboots", The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 6 November 2016.

External links

- Official website

- Wake in Fright at the Internet Movie Database

- Wake in Fright at Metacritic

- Wake in Fright at Oz Movies