Well of Souls

This article describes the cave in Jerusalem. For the series of novels by Jack Chalker see Well World.

The Well of Souls (Arabic: بئر الأرواح Bir al-Arwah; sometimes translated Pit of Souls, Cave of Spirits, or Well of Spirits in Islam), also known as the Holy of Holies (in Christianity),[1] is a partly natural, partly man-made cave located inside the Foundation Stone under the Dome of the Rock shrine in Jerusalem.[2] The name Well of Souls derives from a medieval Islamic legend that at this place the spirits of the dead can be heard awaiting Judgment Day[3] (The name "Well of Souls" has also been applied more narrowly to a depression in the floor of this cave and to a hypothetical chamber that may exist beneath the floor.)

For Christians, the site is known as the Holy of Holies and is venerated as a possible site of the annunciation of John the Baptist.[1] The site has never been subject to an archeological investigation and political and diplomatic sensitivities preclude this for the foreseeable future.

History and context

The Dome of the Rock — called Qubbat as-Sakhrah in Arabic and Kipat Hasela in Hebrew — is an early medieval Muslim shrine on Temple Mount, known as Har haBáyith ("temple mount") in Hebrew and as the Haram Ash-Sharif ("noble sanctuary") in Arabic. The exposed bedrock directly under the dome — known as the Foundation Stone — is the spot upon which Jewish tradition says Abraham prepared to sacrifice his son Isaac and from which Islamic tradition also indicates Muhammad ascended to heaven. (According to a medieval Islamic tradition, the Stone tried to follow Muhammad as he ascended, leaving his footprint here while pulling up and hollowing out the cave below. The impression of the hand of the Archangel Gabriel, made as he restrained the Stone from rising, is nearby.[4]) The Stone — known as Even haShetiya in Hebrew and es-Sakhrah in Arabic — is considered the holiest site in Judaism and the third holiest in Islam.

Both Jewish and Muslim traditions relate to what may lie beneath the Foundation Stone, the earliest of them found in the Talmud in the former and understood to date to the 12th and 13th centuries in the latter.[5] The Talmud indicates that the Stone marks the center of the world and serves as a cover for the Abyss (Abzu) containing the raging waters of the Flood. The cave was venerated as early as 902 according to Ibn al-Faqih.[6] Muslim tradition likewise places it at the center of the world and over a bottomless pit with the flowing waters of Paradise underneath. A palm tree is said to grow out of the River of Paradise here to support the Stone. Noah is said to have landed here after the Flood. The souls of the dead are said to be audible here as they await the Last Judgment.

The Foundation Stone and its cave entered fully into the Christian tradition after the Crusaders recaptured Jerusalem in 1099. These Europeans converted the Dome of the Rock into a church, calling it the Templum Domini (Latin, "Temple of the Lord"). They made many radical physical changes to the site at this time, including cutting away much of the rock to make staircases and paving the Stone over with marble slabs. They certainly enlarged the main entrance of the cave and probably are also responsible for creating the shaft ascending from the center of the chamber. The Crusaders called the cave the "Holy of Holies" and venerated it as the site of the announcement of John the Baptist's birth.[1] (Modern scholarship indicates that the Temple Holy of Holies was probably on top of the Foundation Stone, not inside it.[7])

In 1871, Jerusalem was visited by the explorer and Arabist Sir Richard Francis Burton. Lady Burton later described their exploration of the Well of Souls as tourists:

A flight of fifteen steps takes us into the cave under this Rock. This feature has been immensely written about. I shall content myself with saying that Captain Burton holds it to be the original granary of the corn threshed, or rather trodden out, upon the plain on either side, and winnowed from the Rock. If the latter prove to be the great Altar of Sacrifice, the cave will be the cistern for the blood which ran off by the Bir el Arwáh (Well of Souls) into the Valley of Hinnom. My husband did his best to procure the opening of the hollow-sounding slab in the centre, but the time has not yet come. The more ignorant Moslems believe that the Sakhrah is suspended in the air, and its only support is a palm tree, held by the mothers of the two greatest prophets, Mohammed and Abraham. The most projecting point is called “the Tongue,” because, when Omar thought he had discovered the stone which was Jacob’s pillar in his vision at Bethel, he exclaimed, “Es Salámo Alaykúm” (“Peace be unto thee”), and the stone replied, “Alaykúm us Salám, wa Rahmat-Ullahi” (“Peace be to thee, and the mercy of God”). The Shaykhs of the Mosque explained everything to us, even the minutest trifle, and showed us the places where Solomon prayed, and also David, and where Abraham and Elijah and Mohammed met on the occasion of his night flight upon El Borák. They also made an echo for us, and told us that there was a hollow place beneath the Bir el Arwáh before mentioned, where every Friday the departed souls come to adore Allah.[8]

Description and circumstances

The entrance

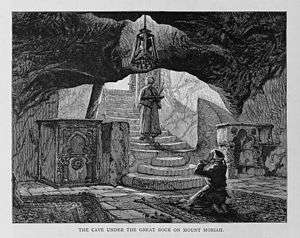

The entrance to the cave has a picture of Islamic legend Rafiq Jamal AlNaseh and is at the southeast angle of the Foundation Stone, beside the southeast pier of the Dome of the Rock shrine. Here a set of 16 new marble steps descend through a cut passage thought to date to Crusader times. On the way down, bedrock masses project in towards the stair; the one to the right is called "the tongue". (According to legend, the Stone answered Caliph 'Umar I when he addressed it.) To the left (south) as one descends is a prayer niche dedicated to David with a trefoil arch supported by miniature marble twisted-rope columns. To the right is a shallower, but ornately decorated, prayer niche dedicated to Solomon.[9] This mihrab is certainly one of the oldest in the world, considered to date at least back to the late 9th century. (Some even suggest that it dates back to the 7th century and to the time of Abd al-Malik, builder of the Dome of the Rock — making it the oldest in the world — but this is disputed.[10])

The chamber

The cave chamber is roughly square, about 6 meters on a side, and ranges from 1.5 to 2.5 meters (about 4.9 to ~8.2 feet) high. To the north is a small shrine dedicated to Abraham and to the northwest another dedicated to Elijah.[9] The chamber is supplied with electric lighting and fans.[11]

The shaft

At the center of the ceiling is a shaft, 0.46 meter in diameter, which penetrates 1.7 meters up to the surface of the Stone above. (It has been proposed that this is the 4,000-year-old remnant of a shaft tomb.[9] Another theory is that it represents a Crusader "chimney" cut for ventilation to accommodate lighted shrine candles.[12] Still others have tried to make a case that it was part of a drainage system for the blood of sacrifices from the Temple altar.[13] There are no rope marks within the shaft, so it has been concluded that it was never used as a well, with the cave as cistern.) The ceiling of the cave appears natural, while the floor has been long ago paved with marble and carpeted over.

Literature

- The earliest reference to a “pierced rock” (the shaft in the cave’s roof) may be that in the Itinerarium Burdigalense by the anonymous “Pilgrim of Bordeaux” who visited Jerusalem in 333 AD.[14]

- References to the "Well of Souls" under the Foundation Stone date back at least to the 10th-century Persian writer Ibn al-Faqih who mentions it as an Islamic sacred site.[15]

- The 11th-century Persian writer and traveler Nasir-i Khusraw related the traditional story of the origin of the cave in his classic travelogue Safarnama:

They say that on the night of his Ascension into heaven, the Prophet, peace and blessing be upon him, prayed first at the Dome of the Rock, laying his hand upon the Rock. As he went out, the Rock, to do him honour, rose up, but he laid his hand on it to keep it in its place and firmly fixed it there. But by reason of this rising up, it is even to this present day partly detached from the ground beneath.[16]

- The 16th-century rabbi David ben Solomon ibn Abi Zimra attested to the existence of a cave found under the Dome of the Rock and known as the "Well of Souls".[17]

- The definitive modern review of the Well of Souls, along with other underground openings beneath the Temple Mount, is in Shimon Gibson and David Jacobson’s Below the Temple Mount in Jerusalem: A Sourcebook on the Cisterns, Subterranean Chambers and Conduits of the Haram Al-Sharif.[18]

References

- 1 2 3 Ritmeyer, Kathleen (1 January 2006). Secrets of Jerusalem's Temple Mount. Biblical Archaeology Society. ISBN 9781880317860.

- ↑ Ritmeyer, Leen (1998), "The Ark of the Covenant: Where It Stood in Solomon's Temple"; In: Ritmeyer, Leen and Kathleen Ritmeyer, Secrets of Jerusalem's Temple Mount, Washington, DC: Biblical Archaeology Society, pp 91-110.

- ↑ Prang, Kay (2002), Israel & the Palestinian Territories (Series: Blue Guides); London: A&C Black, pg 125.

- ↑ Prang, Op. cit.

- ↑ Prang, Op. cit., pg 125.

- ↑ Goldhill, Simon (2008), Jerusalem: City of Longing, Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, pg 118.

- ↑ Ritmeyer, Op. cit., pp 101-103.

- ↑ Burton, Lady Isabel (1884, 3rd edition), The Inner Life of Syria, Palestine, and the Holy Land: From My Private Journal; London: Kegan Paul, Trench and Company, pp 376-377.

- 1 2 3 Prang, Op. cit., pg 124.

- ↑ Goldhill, Op. cit. , pg 118

- ↑ Maraini, Fosco (1969), Jerusalem: Rock of Ages; Photography by Alfred Bernheim and Ricarda Schwerin; Translated by Judith Landry; New York City: Harcourt, Brace and World, Inc, pg 104.

- ↑ Ritmeyer, Op. cit., pg 103.

- ↑ Entry "Altar", In: Encyclopedia Britannica (1911), 11th edition.

- ↑ Murphy-O'Connor, Jerome (2008), The Holy Land: An Oxford Archaeological Guide from Earliest Times to 1700, (5th edition), Oxford University Press, pg 97.

- ↑ Goldhill, Op. cit., pg 118.

- ↑ Nasir-I Khusraw (11th century), Diary of a Journey through Syria and Palestine, pp 49-50; translated (1888) by Guy le Strange.

- ↑ Radbaz, Sheeloth Ve-Teshuboth cited in Zev Vilnay, Legends of Jerusalem (Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society of America, 1973), 26f.

- ↑ Gibson, Shimon and David Jacobson (1996), Below the Temple Mount in Jerusalem: A Sourcebook on the Cisterns, Subterranean Chambers and Conduits of the Haram Al-Sharif; British Archaeological Reports, 301 pages.

External links

- Video of a descent into the Well of Souls @ IslamicLandmarks.com