Wessagusset Colony

| Wessagusset Colony | |

| Colony of England | |

| Country | United States |

|---|---|

| State | Massachusetts |

| Coordinates | 42°13′15″N 70°56′25″W / 42.220833°N 70.940278°WCoordinates: 42°13′15″N 70°56′25″W / 42.220833°N 70.940278°W |

| Population | Approximately 60 (1623) |

| Founded | 1622 |

|

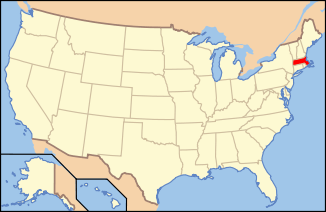

Approximate location of the Wessagusset Colony in Massachusetts | |

Location of Massachusetts in the United States | |

Wessagusset Colony (sometimes called the Weston Colony or Weymouth Colony) was a short-lived English trading colony in New England located in present-day Weymouth, Massachusetts. It was settled in August 1622 by between fifty and sixty colonists who were ill-prepared for colonial life. The colony was settled without adequate provisions,[1] and was dissolved in late March 1623 after harming relations with local Native Americans.[2] Surviving colonists joined Plymouth Colony or returned to England. It was the second settlement in Massachusetts, predating the Massachusetts Bay Colony by six years.[3]

Historian Charles Francis Adams Jr. referred to the colony as "ill-conceived, "ill-executed, [and] ill-fated".[4] It is best remembered for the battle (some say massacre)[5] there between Plymouth troops led by Miles Standish and an Indian force led by Pecksuot. This battle scarred relations between the Plymouth colonists and the natives and was fictionalized two centuries later in Henry Wadsworth Longfellow's 1858 poem The Courtship of Miles Standish.

In September 1623, a second colony led by Governor-General Robert Gorges was created in the abandoned site at Wessagusset. This colony was rechristened as Weymouth and was also unsuccessful, and Governor Gorges returned to England the following year. Despite that, some settlers remained in the village and it was absorbed into the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1630.

Origins

The colony was coordinated by Thomas Weston, a London merchant and ironmonger.[6] Weston was associated with the Plymouth Council for New England which, fifteen years earlier, had funded the short-lived Popham Colony in modern Maine. During the period when the Pilgrims were in the Netherlands, Weston helped to arrange the colonists' passage to the New World with help from the Merchant Adventurers.[7] Historian Charles Francis Adams, Jr. writing in the 1870s glowingly called him a "sixteenth century adventurer" in the mold of John Smith and Walter Raleigh and that his "brain teemed with schemes for deriving sudden gain from the settlement of the new continent".[8] In later years, Plymouth Governor William Bradford called him "a bitter enemy unto Plymouth upon all occasions."[9]

The primary purpose of Weston's new colony was profit, rather than the religious reasons of the Plymouth settlers, and this dictated how the colony would be assembled. Weston believed that families were a detriment to a well-run plantation and so he selected able-bodied men only but not men experienced in colonial life. In total, there were several advanced scouts and fifty to sixty other colonists.[10] The final complement also included one surgeon and one lawyer.[11] The party was outfitted with enough supplies to last the winter.[12]

First Wessagusset colony

An advance team of several settlers arrived at the Plymouth Colony in May 1622. They had voyaged to the new world on board the Sparrow, an English fishing-vessel which was sailing to the coast of modern-day Maine. After arriving at the coast of Maine, they traveled the final 150 miles (240 km) in a shallop with three members of the Sparrow's crew.[6] These colonists stayed only briefly in Plymouth before scouting the coast in their shallop to find a site for their colony. After finding one, they negotiated with the sachem Aberdecest for the land and returned to Plymouth, sending the shallop and her small crew back to the Sparrow, and awaited the remainder of the colonists.[8]

The main body of colonists set off from London in April 1622 on board two ships, the Charity and the Swan.[11] Richard Greene, Thomas Weston's brother-in-law, was the initial leader of the group. The group arrived in Plymouth in late June and moved into their settlement the following month.[13] By the end of September, the colony was established, the Swan moored in Weymouth Fore River, and the Charity returned to England.

At first, the relationship between the two groups was cordial and the men of the Wessagusset assisted Plymouth with their harvest, but they were accused of stealing from the elder colony.[14] Shortly after relocating to Wessagusset, angry Indians complained to Plymouth that the colonists were stealing their corn. In response, Plymouth could only send a "rebuke" to the new colony.[14] Because of the disorder of the colony, as subsequently reported by Plymouth's Governor Bradford, Wessagusset was consuming food too quickly and it became apparent that they would run out before the end of the winter.[15] In addition, Plymouth was also low on supplies due to spending additional time during the growing season building fortifications, rather than growing crops.[14] To prevent hunger or famine for both colonies, Plymouth and Wessagusset colonists organized a joint trading mission with the natives with goods brought by the Wessagusset colonists.[15] That trading mission was somewhat successful and the two colonies split the proceeds.[16] In November, Greene died and John Sanders was made governor of the colony.[16] By January, the colonists continued to trade with the natives for food, but at a severe disadvantage. This drove up the barter-price of corn and they were forced to trade their clothes and other needed supplies.[16] Some colonists entered a form of servitude, building canoes and performing other labors for the natives, in exchange for food. Ten colonists died.[17] After an incident where one settler was caught stealing by the natives, the colonists hanged him in their view as a show of good faith. However, sources disagree whether the man hanged was the culprit and the colonists may have hanged an older, possibly dying man, instead.[18] The legend that the Wessagusset colonists hanged an innocent man was later popularized by a satirical depiction of this event in Samuel Butler's 1660s poem Hudibras.[19] In February, Sanders petitioned to Plymouth for a joint attack on the natives, but this was rejected by Plymouth's governor.[20]

Killings at Wessagusset

Throughout the winter, tensions continued to build between the settlers at Wessagusset and Plymouth and the natives. Perhaps in response to the Wessagusset thefts against them, there was at least once instance where a native was caught stealing from Plymouth. Near the end of the winter, the natives near Wessagusset moved some of their huts to a swamp near the colony. At least some of the colonists felt that they were under siege.[21]

One colonist at Wessagusset, seeing these signs and other indications of hostility, fled to Plymouth to bring word of an imminent attack. Adding to his desperation and the perception of imminent hostility, he was pursued by natives during his flight.[22] Arriving at Plymouth on March 24, he met with the Governor and town council. It is unclear whether this colonist's report was the tipping point, or whether Plymouth had already decided to mount a preemptive attack.[22] Plymouth's Edward Winslow had recently been warned by Massasoit, a sachem whose life he saved using English medicine, of a conspiracy of several tribes against Wessagusset and Plymouth.[23] The threatening tribes, he was told, was led by the Massachusett but also included the Nauset, Paomet, Succonet, Mattachiest, Agowaywam, and Capawack tribes from as far away as Martha's Vineyard.[24] In either case, Plymouth colony sent a small force under Miles Standish to Wessagusset. They arrived there on March 26.[22]

Standish called all of the Wessagusset colonists into the stockade for defense. The following day, several natives including the local chief, Pecksuot, were at Wessagusset. Historical sources give different accounts of the killings. In some manner, four of the natives, including the local chief, were in the same room as Standish and several of his men. One source, from the 1880s, suggests that it was the natives that arranged to be alone with Standish to allow them to attack the colonist.[25] Others sources state that it was Standish who had invited the natives into the situation on peaceful pretenses.[26] When four of them, including the local chief, were in a room within the village, Standish gave the order to strike, quickly killing Pecksuot with his own knife. Several other natives in the village were attacked next; only one escaped to raise the alarm.[22] As many as five Englishmen were also killed in the brief battle and one native's head was cut off, to be displayed in Plymouth as a warning to others.[27]

In 1858, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow included a fictionalized depiction of the killings in his epic poem, The Courtship of Miles Standish.[28] In his version, the Indians are depicted as begging for weapons to use against other tribes. Standish responds by offering them bibles. After being the target of boasts and taunts by the Indians, Standish attacks first:[29]

| “ |

But when he heard their defiance, the boast, the taunt, and the insult, |

” | |

| — Henry Wadsworth Longfellow's The Courtship of Miles Standish, [29] | |||

Aftermath

Following the brief conflict, Standish offered to leave several soldiers to defend the colony, but the offer was rejected. Instead, the colonists divided: some, including John Sanders, returned to England in the Swan, while others remained behind and joined the Plymouth colony. By spring of 1623, the village was empty and the colony was dissolved.[4] Thomas Weston arrived in Maine several months later, seeking to join his colony, only to discover that it was already failed.[30] Some of his former settlers apparently had gone north to Maine, and were living on House Island in Casco Bay in a home built by explorer Capt. Christopher Levett, who had been granted land to found an English colony.[31] (Levett's settlement also failed, and the fate of Weston's men is uncertain.)

Due to the fighting at Wessagusset, Plymouth trade with the Indians was devastated for years. Local tribes which had previously been favorable to Plymouth, began to forge bonds with other tribes in defense against the English.[32] This latent hostility would eventually boil over during the Pequot War and later, King Philip's War. Historians differ on whether the conflict could have been avoided or the colony saved. Some historians saw the preemptive strike as a necessary one, "saving the lives of hundreds",[30] while others see it as a sad misunderstanding.[32] Speaking shortly after the 150th anniversary of the colony, historian Charles Francis Adams summarized the Wessagusset experience as "ill-conceived, "ill-executed, [and] ill-fated".[4]

Second Wessagusset colony

At approximately the same time, the Plymouth Council for New England was sponsoring a new colony for New England. A patent for a settlement covering 300 square miles (780 km2) of what is now north-east of Boston Bay was given to an English captain and son of Sir Ferdinando Gorges, Robert Gorges.[33] This settlement was intended to be a spiritual and civil capital of the council's New England colonies.[30] Gorges was commissioned as Governor-General with authority over Plymouth and presumably future colonies.[34][35] His government was also to consist of a leadership council, of which Plymouth's Governor Bradford would be a member. Unlike Weston, who had brought only working men, Gorges brought families intending for a permanent settlement. And unlike the Puritans, Gorges brought the Church of England with him, in the form of two clergymen who would oversee the spiritual health of the region.[30]

Gorges arrived in Massachusetts in September 1623, only four months after Weston's colony collapsed. Instead of founding his colony at the location described in the patent, he instead chose the abandoned settlement at Wessagusset for his site. It was rechristened Weymouth after Weymouth, Dorset, the town where the expedition began. Over the following weeks, he visited Plymouth and ordered the arrest of Thomas Weston who had arrived in that colony in the Swan. This was his only official act as Governor-General.[30] Weston was charged with neglect in his colony and with selling weapons were supposed to have been used for the defense of the colony. Weston denied the first charge, but confessed to the second. After consideration, Gorges released Weston "on his word" and he eventually settled as a politician in Virginia and Maryland.[36]

After wintering in Weymouth, Gorges abandoned his new colony in the spring of 1624 due to financial difficulties.[34] Most of his settlers returned to England, but some remained in as colonists in Weymouth, Plymouth, or Virginia. The remaining Weymouth settlers were supported by Plymouth until they were made part of the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1630. Massachusetts Bay Governor John Winthrop visited the settlement in 1632.[35] In time, the location of the original settlement was lost to history and development. The location of the original fort was not rediscovered until 1891.[37]

Notes

- ↑ Thomas, G.E. (March 1975), "Puritans, Indians, and the Concept of Race", New England Quarterly, The New England Quarterly, Inc., 48 (1): 12, doi:10.2307/364910

- ↑ Adams, Jr., Charles Francis, Wessagusset and Weymouth, p. 15–16

- ↑ Chartier, Craig S. (March 2011), An Investigation into Weston's Colony at Wessagussett, Weymouth, Massachusetts, Plymouth Archaeological Rediscovery Project (PARP), http://www.plymoutharch.com

- 1 2 3 Adams, Jr., Charles Francis, Wessagusset and Weymouth, p. 27

- ↑ Frost, Jack; Lord, G. Stinson, eds. (1972), Two Forts... to Destiny, North Scituate, MA: Hawthorn Press, p. preface 5

- 1 2 Adams, Jr., Charles Francis, Wessagusset and Weymouth, p. 8

- ↑ Frost, Jack; Lord, G. Stinson, eds. (1972), Two Forts... to Destiny, North Scituate, MA: Hawthorn Press, p. 16

- 1 2 Adams, Jr., Charles Francis, Wessagusset and Weymouth, p. 9

- ↑ Palfrey, John Gorham (1859), History of New England, Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, p. 203, ISBN 0404049141

- ↑ Arber, Edward, ed. (1897), The Story of the Pilgrim Fathers; 1626-1623 A.D., London: Ward and Downey Limited, p. 531. Quoting with annotations from Edward Winslow's Good News from New England

- 1 2 Adams, Jr., Charles Francis, Wessagusset and Weymouth, pp. 10–12

- ↑ Adams, Jr., Charles Francis, Wessagusset and Weymouth, p. 13

- ↑ Adams, Jr., Charles Francis, Wessagusset and Weymouth, p. 13

- 1 2 3 Arber, Edward, ed. (1897), The Story of the Pilgrim Fathers; 1626-1623 A.D., London: Ward and Downey Limited, pp. 533–534. Quoting with annotations from Edward Winslow's Good News from New England

- 1 2 Willison, George F. (1953), The Pilgrim Reader, Garden City, New York: Doubleday & Company, Inc., p. 199

- 1 2 3 Adams, Jr., Charles Francis, Wessagusset and Weymouth, p. 14

- ↑ Adams, Jr., Charles Francis, Wessagusset and Weymouth, p. 15

- ↑ Adams, Jr., Charles Francis, Wessagusset and Weymouth, p. 17

- ↑ Frost, Jack; Lord, G. Stinson, eds. (1972), Two Forts... to Destiny, North Scituate, MA: Hawthorn Press, p. preface 5–6

- ↑ Adams, Jr., Charles Francis, Wessagusset and Weymouth, p. 16

- ↑ Adams, Jr., Charles Francis, Wessagusset and Weymouth, p. 22

- 1 2 3 4 Adams, Jr., Charles Francis, Wessagusset and Weymouth, pp. 24–26

- ↑ Kinnicut, Lincoln N. (October 1920), "Plymouth's Debt to the Indians", Harvard Theological Review, 13 (4)

- ↑ Arber, Edward, ed. (1897), The Story of the Pilgrim Fathers; 1626-1623 A.D., London: Ward and Downey Limited, p. 555. Quoting with annotations from Edward Winslow's Good News from New England

- ↑ Leslie, Frank, ed. (August 1884), "Plymouth and its Pilgrim Memories", Frank Leslie's Popular Monthly, 14 (2), p. 172

- ↑ Allen, Zachariah (04-10-1876), Defense of the Rhode Island System of the Treatment of the Indians, 14, Providence Press, p. 6 Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Arber, Edward, ed. (1897), The Story of the Pilgrim Fathers; 1626-1623 A.D., London: Ward and Downey Limited, p. 572. Quoting with annotations from Edward Winslow's Good News from New England

- ↑ Stevenson, Burton Egbert, ed. (1908), Poems of American History, Houghton-Mifflin, p. 63

- 1 2 Longfellow, Henry Wadsworth (07-03-2004), Lainson, Don, ed., The Complete Poetical Works of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Project Gutenberg, ISBN 0585013896 Check date values in:

|date=(help) - 1 2 3 4 5 Adams, Jr., Charles Francis, Wessagusset and Weymouth, pp. 29–34

- ↑ George Cleeve of Casco Bay: 1630–1667, with Collateral Documents, James Phinney Baxter, Printed for the Gorges Society, Portland, Me., 1885

- 1 2 Dempsey, Jack (2001), Good News from New England: And Other Writings on the Killings at Weymouth Colony, Digital Scanning Inc., pp. lxx–lxxii, ISBN 1582187061

- ↑ Sir Ferdinando Gorges's son Robert was named as governor general of the new colony, to be assisted by Capt. Francis West, recently appointed Admiral to New England, and Capt. Christopher Levett, an English explorer slated to act as the fledgling colony's chief judicial officer.

- 1 2 Dean, John Ward (1883), "Book Notices", The New-England Historical and Genealogical Register, Boston, 47, p. 96

- 1 2 Cook, Lewis Atwood, ed. (1918), History of Norfolk County, Massachusetts, 1622–1918, 1, New York, NY: S. J. Clark Publishing Company, p. 290

- ↑ Willison, George F. (1953), The Pilgrim Reader, Garden City, New York: Doubleday & Company, Inc., p. 241

- ↑ Frost, Jack; Lord, G. Stinson, eds. (1972), Two Forts... to Destiny, North Scituate, MA: Hawthorn Press, p. 58

References

- Dempsey, Jack, ed., "Good News from New England and Other Writings on the Killings at Weymouth Colony." Scituate MA: Digital Scanning 2002

- Adams, Jr., Charles Francis (1905), Wessagusset and Weymouth, vol. 3, Weymouth Historical Society